Penal labour

Penal labour is a generic term for various kinds of unfree labour which prisoners are required to perform, typically manual labour. The work may be light or hard, depending on the context. Forms of sentence involving penal labour have included involuntary servitude, penal servitude and imprisonment with hard labour. The term may refer to several related scenarios: labour as a form of punishment, the prison system used as a means to secure labour, and labour as providing occupation for convicts. These scenarios can be applied to those imprisoned for political, religious, war, or other reasons as well as to criminal convicts.

Large-scale implementations of penal labour include labour camps, prison farms, penal colonies, penal military units, penal transportation, or aboard prison ships.

Punitive versus productive labour

Punitive labour, also known as convict labour, prison labour, or hard labour, is a form of forced labour used in both past and present as an additional form of punishment beyond imprisonment alone. Punitive labour encompasses two types: productive labour, such as industrial work; and intrinsically pointless tasks used as primitive occupational therapy, punishment and/or physical torment.

Sometimes authorities turn prison labour into an industry, as on a prison farm or in a prison workshop. In such cases, the pursuit of income from their productive labour may even overtake the preoccupation with punishment and/or reeducation as such of the prisoners, who are then at risk of being exploited as slave-like cheap labour (profit may be minor after expenses, e.g. on security).

On the other hand, for example in Victorian prisons, inmates commonly were made to work the treadmill: in some cases, this was productive labour to grind grain; in others, it served no purpose. Similar punishments included turning the crank machine or carrying cannonballs.[1] Semi-punitive labour also included oakum-picking: teasing apart old tarry rope to make caulking material for sailing vessels.

British Empire

Imprisonment with hard labour was first introduced into English law with the Criminal Law Act 1776 (6 Geo III c 43),[2] also known as the "Hulks Act", which authorized prisoners being put to work on improving the navigation of the River Thames in lieu of transportation to the North American colonies, which had become impossible due to the American Revolutionary War.[3]

The Penal Servitude Act 1853 (16 & 17 Vict c 99)[4] substituted penal servitude for transportation to a distant British colony, except in cases where a person could be sentenced to transportation for life or for a term not less than fourteen years. Section 2 of the Penal Servitude Act 1857 (20 & 21 Vict c 3)[5] abolished the sentence of transportation in all cases and provided that in all cases a person who would otherwise have been liable to transportation would be liable to penal servitude instead. Section 1 of the Penal Servitude Act 1891[6] makes provision for enactments which authorise a sentence of penal servitude but do not specify a maximum duration. It must now be read subject to section 1(1) of the Criminal Justice Act 1948.

Sentences of penal servitude were served in convict prisons and were controlled by the Home Office and the Prison Commissioners. After sentencing, convicts would be classified according to the seriousness of the offence of which they were convicted and their criminal record. First time offenders would be classified in the Star class; persons not suitable for the Star class, but without serious convictions would be classified in the intermediate class. Habitual offenders would be classified in the Recidivist class. Care was taken to ensure that convicts in one class did not mix with convicts in another.

Penal servitude included hard labour as a standard feature. Although it was prescribed for severe crimes (e.g. rape, attempted murder, wounding with intent, by the Offences against the Person Act 1861) it was also widely applied in cases of minor crime, such as petty theft and vagrancy, as well as victimless behaviour deemed harmful to the fabric of society. Notable recipients of hard labour under British law include Oscar Wilde (after his conviction for gross indecency) and John William Gott (a terminally ill trouser salesman convicted of blasphemy).

Labour was sometimes useful. In Inveraray Jail from 1839 prisoners worked up to ten hours a day. Most male prisoners made herring nets or picked oakum (Inveraray was a busy herring port); those with skills were often employed where the skills could be used, such as shoemaking, tailoring or joinery. Female prisoners picked oakum, knitted stockings or sewed.[1]

Forms of labour for punishment included the treadmill, shot drill, and the crank machine.[1]

Treadmills for punishment were used in prisons in Britain from 1818 until the second half of the 19th century; they often took the form of large paddle wheels some 20 feet in diameter with 24 steps around a six-foot cylinder. Prisoners had to work six or more hours a day, climbing the equivalent of 5,000 to 14,000 vertical feet. While the purpose was mainly punitive, the mills could have been used to grind grain, pump water, or operate a ventilation system.[7]

Shot drill involved stooping without bending the knees, lifting a heavy cannonball slowly to chest height, taking three steps to the right, replacing it on the ground, stepping back three paces, and repeating, moving cannonballs from one pile to another.[1]

The crank machine was a device which turned a crank by hand which in turn forced four large cups or ladles through sand inside a drum, doing nothing useful. Male prisoners had to turn the handle 14,400 times a day, as registered on a dial. The warder could make the task harder by tightening an adjusting screw, hence the slang term "screw" for prison warder.[1]

The British penal colonies in Australia between 1788 and 1868 provide a major historical example of convict labour, as described above: during that period, Australia received thousands of transported convict labourers, many of whom had received harsh sentences for minor misdemeanours in Britain or Ireland.

As late as 1885, 75% of all prison inmates were involved in some sort of productive endeavour, mostly in private contract and leasing systems. By 1935 the portion of prisoners working had fallen to 44%, and almost 90% of those worked in state-run programmes rather than for private contractors.[8]

England and Wales

Penal servitude was abolished for England and Wales by section 1(1) of the Criminal Justice Act 1948.[9] Every enactment conferring power on a court to pass a sentence of penal servitude in any case must be construed as conferring power to pass a sentence of imprisonment for a term not exceeding the maximum term of penal servitude for which a sentence could have been passed in that case immediately before the commencement of that Act.

Imprisonment with hard labour was abolished by section 1(2) of that Act.

Northern Ireland

Penal servitude was abolished for Northern Ireland by section 1(1) of the Criminal Justice Act (Northern Ireland) 1953.[10] Every enactment which operated to empower a court to pass a sentence of penal servitude in any case now operates so as to empower that court to pass a sentence of imprisonment for a term not exceeding the maximum term of penal servitude for which a sentence could have been passed in that case immediately before the commencement of that Act.

Imprisonment with hard labour was abolished by section 1(2) of that Act.

Scotland

Penal Servitude was abolished for Scotland by section 16(1) of the Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 1949 on 12 June 1950.

Imprisonment with hard labour was abolished by section 16(2) of that Act.

Every enactment conferring power on a court to pass a sentence of penal servitude in any case must be construed as conferring power to pass a sentence of imprisonment for a term not exceeding the maximum term of penal servitude for which a sentence could have been passed in that case immediately before 12 June 1950. But this does not empower any court, other than the High Court, to pass a sentence of imprisonment for a term exceeding three years.

See section 221 of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1975 and section 307(4) of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995

New Zealand

The Criminal Justice Act 1954 abolished the distinction between imprisonment with and without hard labour and replaced 'reformative detention' with 'corrective training',[11] which was later abolished on 30 June 2002.[12]

France

Prison inmates can work [13] either for the prison (directly, by performing tasks linked to prison operation, or for the Régie Industrielle des Établissements Pénitentiaires, which produces and sells merchandises) or for a private company, in the framework of a prison/company agreement for leasing inmate labour. Work ceased being compulsory for sentenced inmates in France in 1987. From the French Revolution of 1789, the prison system has been governed by a new penal code.[14] Some prisons became quasi-factories, in the nineteenth century, many discussions focused on the issue of competition between free labour and prison labour. Prison work was temporarily prohibited during the revolution of 1848. Prison labour then specialised in the production of goods sold to government departments (and directly to prisons, for example guards' uniforms), or in small low-skilled manual labour (mainly subcontracting to small local industries).[15]

China

In pre-Maoist China, a system of labor camps for political prisoners operated by the Kuomintang forces of Chiang Kai-shek existed during the Chinese Civil War from 1938–1949. Young activists and students accused of supporting Mao Zedong and his Communists were arrested and re-educated in the spirit of anti-communism at the Northwestern Youth Labor Camp.[16]

After the Communists took power in 1949 and established the People's Republic of China, laojiao (Re-education through labor) and laogai (Reform through labor) was (and still is in some cases) used as a way to punish political prisoners. They were intended not only for criminals, but also for those deemed to be counter-revolutionary (political and/or religious prisoners).[17] According to a Al Jazeera special report on slavery, China has the largest penal labour system in the world today. Often these prisoners are used to produce products for export to the West.[18]

North Korea

North Korean prison camps can be differentiated into internment camps for political prisoners (Kwan-li-so in Korean) and reeducation camps (Kyo-hwa-so in Korean).[19] According to human rights organizations, the prisoners face forced hard labor in all North Korean prison camps.[20][21] The conditions are harsh and life-threatening[22] and prisoners are subject to torture and inhumane treatment.[23][24]

Japan

Most Japanese prisoners are required to engage in prison labour, often in manufacturing parts which are then sold cheaply to private Japanese companies. This practice has raised charges of unfair competition since the prisoners' wages are far below market rate.

The Netherlands

(Hard) penal labour does not exist in the Netherlands, but a light variant (Dutch: taakstraf) is one of the four primary punishments which can be imposed on a convicted offender.[25] The person who is sentenced to a taakstraf must perform some service to the community. The maximum punishment is 240 hours, according to article 22c, part 2 of Wetboek van Strafrecht.[26] The labour must be done in his free time. Reclassering Nederland keeps track of those who were sentenced to taakstraffen.[27][28]

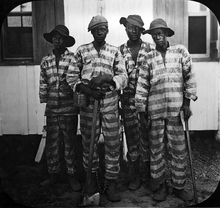

United States

Federal Prison Industries (UNICOR or FPI) is a wholly owned United States government corporation created in 1934 that uses penal labor from the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) to produce goods and services. FPI is restricted to selling its products and services to federal government agencies and has no access to the commercial market.[29] State prison systems also use penal labor and have their own penal labor divisions.

The 13th Amendment of the American Constitution in 1865 explicitly allows penal labor as it states that "neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for a crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction."[30][31] Unconvicted detainees awaiting trial cannot be forced to participate in forced rehabilitative labor programs in prison as it violates the Thirteenth Amendment.

The "convict lease" system became popular throughout the South following the American Civil War and into the 20th century. Since the impoverished state governments could not afford penitentiaries, they leased out prisoners to work at private firms. Reformers abolished convict leasing in the 20th-century Progressive Era. At the same time, labor has been required at many prisons.

In 1934, federal prison officials concerned about growing unrest in prisons lobbied to create a work program. Private companies got involved again in 1979, when Congress passed a law establishing the Prison Industry Enhancement Certification Program which allows employment opportunities for prisoners in some circumstances.[32]

Penal labor is sometimes used as a punishment in the U.S. military.[33]

Over the years, the courts have held that inmates may be required to work and are not protected by the constitutional prohibition against involuntary servitude.[34] Correctional standards promulgated by the American Correctional Association provide that sentenced inmates, who are generally housed in maximum, medium, or minimum security prisons, be required to work and be paid for that work.[35] Some states require, as with Arizona, all able-bodied inmates to work.[36]

Republic of Ireland

Penal servitude was abolished for the Republic of Ireland by section 11(1) of the Criminal Law Act, 1997.[37]

Every enactment conferring a power on a court to pass a sentence of penal servitude in any case must be treated as an enactment empowering that court to pass a sentence of imprisonment for a term not exceeding the maximum term of penal servitude for which a sentence could have been passed in that case immediately before the commencement of the Criminal Law Act 1997.

In the case of any enactment in force on 5 August 1891 (the date on which section 1 of the Penal Servitude Act 1891 came into force) whereby a court had, immediately before the commencement of the Criminal Law Act 1997, power to pass a sentence of penal servitude, the maximum term of imprisonment may not exceed five years or any greater term authorised by the enactment.

Imprisonment with hard labour was abolished by section 11(3) of that Act.

Soviet Union

Another historically significant example of forced labour was that of political prisoners and other persecuted people in labour camps, especially in totalitarian regimes since the 20th century where millions of convicts were exploited and often killed by hard labour and bad living conditions. For much of the history of the Soviet Union and other Communist states, political opponents of these governments were often sentenced to forced labour camps. The Soviet Gulag camps were a continuation of the punitive labour system of Imperial Russia known as katorga, but on a larger scale. Most inmates in the Gulag were ordinary criminals: between 1934 and 1953 there were only two years, 1946 and 1947, when the number counter-revolutionary prisoners exceeded that of ordinary criminals, partly because the Soviet state had amnestied 1 million ordinary criminals as part of the victory celebrations in 1945.[38]:343 At the height of the purges in the 1930s political prisoners made up 12 percent of the camp population; at the time of Stalin's death just over one-quarter. In the 1930s, many ordinary criminals were guilty of crimes that would have been punished with a fine or community service in the 1920s. They were victims of harsher laws from the early 1930s, driven, in part, by the need for more prison camp labor.[39]:930

Between 1930 and 1960, the Soviet regime created many Lager labour camps in Siberia and Central Asia.[40][41] There were at least 476 separate camp complexes, each one comprising hundreds, even thousands of individual camps.[42] It is estimated that there may have been 5-7 million people in these camps at any one time. In later years the camps also held victims of Joseph Stalin's purges as well as World War II prisoners. It is possible that approximately 10% of prisoners died each year.[43] Out of the 91,000 Germans captured alive after the Battle of Stalingrad, only 6,000 survived the Gulag and returned home.[44] Many of these prisoners, however, had died of illness contracted during the siege of Stalingrad and in the forced march into captivity.[45] More than half of all deaths occurred in 1941-1944, mostly as a result of the deteriorating food and medicine supplies caused by wartime shortages.[39]:927

Probably the worst of the camp complexes were the three built north of the Arctic Circle at Kolyma, Norilsk and Vorkuta.[46][47] Prisoners in Soviet labour camps were worked to death with a mix of extreme production quotas, brutality, hunger and the harsh elements.[48] In all, more than 18 million people passed through the Gulag,[49] with further millions being deported and exiled to remote areas of the Soviet Union.[50] The fatality rate was as high as 80% during the first months in many camps. Immediately after the start of the German invasion of the Soviet Union during World War II, the NKVD massacred about 100,000 prisoners who awaited deportation either to NKVD prisons in Moscow or to the Gulag. Michael McFaul, in his New York Times article of 11 June 2003, entitled 'Books of the Times; Camps of Terror, Often Overlooked',[51] has this to say about the state of contemporary dialogue on Soviet slavery:

It should now be known to all serious scholars that the camps began under Lenin and not Stalin. It should be recognized by all that people were sent to the camps not because of what they did, but because of who they were. Some may be surprised to learn about the economic function that the camps were designed to perform. Under Stalin, the camps were simply a crueler but equally inefficient way to exploit labor in the cause of building socialism than the one practiced outside the camps in the Soviet Union. Yet, even this economic role of the camps has been exposed before.

What is remarkable is that the facts about this monstrous system so well documented in Applebaum's book are still so poorly known and even, by some, contested. For decades, academic historians have gravitated away from event-focused history and toward social history. Yet, the social history of the gulag somehow has escaped notice. Compared with the volumes and volumes written about the Holocaust, the literature on the gulag is thin.

The article draws attention to Anne Applebaum's Pulitzer Prize-winning text Gulag: A History.[52]

Non-punitive prison labour

In a number of penal systems, the inmates have the possibility of a job. This may serve several purposes. One goal is to give an inmate a meaningful way to occupy their prison time and a possibility of earning some money. It may also play an important role in resocialisation: inmates may acquire skills that would help them to find a job after release. It may also have an important penological function: reducing the monotony of prison life for the inmate, keeping inmates busy on productive activities, rather than, for example, potentially violent or antisocial activities, and helping to increase inmate fitness, and thus decrease health problems, rather than letting inmates succumb to a sedentary lifestyle.[53]

The classic occupation in 20th-century British prisons was sewing mailbags. This has diversified into areas such as engineering, furniture making, desktop publishing, repairing wheelchairs and producing traffic signs, but such opportunities are not widely available, and many prisoners who work perform routine prison maintenance tasks (such as in the prison kitchen) or obsolete unskilled assembly work (such as in the prison laundry) that is argued to be no preparation for work after release.[54] Classic 20th-century American prisoner work involved making license plates; the task is still being performed by inmates in certain areas.[55]

–David Cameron, former UK Prime Minister[56]

A significant amount of controversy has arisen with regard to the use of prison labour if the prison in question is privatized. Many of these privatized prisons exist in the Southern United States, where roughly 7% of the prison population are within privately owned institutions.[57] Goods produced through this penal labour are regulated through the Ashurst-Sumners Act which criminalizes the interstate transport of such goods.

The advent of automated production in the 20th and 21st century has reduced the availability of unskilled physical work for inmates.

ONE3ONE Solutions, formerly the Prison Industries Unit in Britain, has proposed the development of in-house prison call centers.[58]

See also

- Ashurst-Sumners Act

- Chain gang

- Convict lease

- Coproduction of public services by service users and communities

- Galley slave

- Trusty system

- UNICOR

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Inveraray Jail and County Court, Life in Jail".

- ↑ "Public Act, 16 George III, c. 43". The National Archives. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ↑ Emsley, Clive; Hitchcock, Tim; Shoemaker, Robert (March 2015). "Crime and Justice - Punishments at the Old Bailey". www.oldbaileyonline.org. Old Bailey Proceedings Online. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ↑ , long titled "An Act to substitute, in certain Cases, other Punishment in lieu of Transportation",Short Titles Act 1896

- ↑ Section 2 of the Penal Servitude Act 1857

- ↑ Section 1 of the Penal Servitude Act 1891

- ↑ Thompson, Irene. "The A-Z of Punishment and Torture". BeWrite Books – via Google Books.

- ↑ Reynolds, Morgan O. (1994). "Using the Private Sector to Deter Crime". National Center for Policy Analysis: 33.

- ↑ section 1(1) of the Criminal Justice Act 1948

- ↑ section 1(1) of the Criminal Justice Act (Northern Ireland) 1953

- ↑ SYMON, TONI (2012). "PAPARUA MEN’S PRISON: A SOCIAL AND POLITICAL HISTORY" (PDF). Department of Sociology. University of Canterbury, Christchurch.

- ↑ "4 Custodial sentences and remands — Ministry of Justice, New Zealand". www.justice.govt.nz. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- ↑ Guilbaud, Fabrice. "Working in Prison: Time as Experienced by Inmate-Workers", Revue française de sociologie, vol. vol. 51, no. 5, 2010, pp. 41-68.

- ↑ Patricia O'Brien, The Promise of Punishment: Prisons in Nineteenth-century France, Princeton University Press, 1982

- ↑ Guilbaud, Fabrice. "To Challenge and Suffer: The Forms and Foundations of Working Inmates’ Social Criticism", Sociétés contemporaines 3/2012 (No 87)

- ↑ Mühlhahn, Klaus (2009). Criminal Justice in China: A History. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press ISBN 978-0-674-03323-8. pp. 132-133.

- ↑ "CNN In-Depth Specials - Visions of China - Red Giant: Labor camps reinforce China's totalitarian rule". Cnn.com. 1984-10-09. Retrieved 2013-09-06.

- ↑ "Al Jazeera slavery debate in full". YouTube. 2011-11-25. Retrieved 2013-09-06.

- ↑ "The Hidden Gulag – Part Two: Kwan-li-so political panel-labor colonies (page 25 - 82), Part Three: Kyo-hwa-so long-term prison-labor facilities (page 82 - 110)" (PDF). The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ↑ "Political Prison Camps in North Korea Today" (PDF), Database Center for North Korean Human Rights, pp. 406–428, 15 July 2011, archived from the original (PDF) on 28 February 2013, retrieved 7 February 2014 Chapter 4 Current Status of Compulsory Labor

- ↑ "North Korea: Political Prison Camps" (PDF). Amnesty International. 4 May 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- ↑ "2009 Human Rights Report: Democratic People's Republic of Korea". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ↑ Nicholas D. Kristof (14 July 1996). "Survivors Report Torture in North Korea Labor Camps". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ↑ "North Korea: Torture, death penalty and abductions". Amnesty International. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ↑ "wetten.nl - Wet- en regelgeving - Wetboek van Strafrecht - BWBR0001854" (in Dutch). Wetten.overheid.nl. 2012-12-27. Retrieved 2013-09-06.

- ↑ "wetten.nl - Wet- en regelgeving - Wetboek van Strafrecht - BWBR0001854" (in Dutch). Wetten.overheid.nl. 2012-12-27. Retrieved 2013-09-06.

- ↑ "Home :: Reclassering Nederland". Reclassering.nl. Retrieved 2013-09-06.

- ↑ "Werkstraf - Reclassering Nederland". YouTube. 2012-08-31. Retrieved 2013-09-06.

- ↑ McCollum, William (1996). Federal Prison Industries, Inc: Hearing Before the Committee on the Judiciary, U.S. House of Representatives. DIANE Publishing. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-7567-0060-7.

- ↑ Tsesis, The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom (2004), pp. 17 & 34. "It rendered all clauses directly dealing with slavery null and altered the meaning of other clauses that had originally been designed to protect the institution of slavery."

- ↑ "The Thirteenth Amendment", Primary Documents in American History, Library of Congress. Retrieved 15 February 2007

- ↑ Walshe, Sadhbh (2012). "How US prison labour pads corporate profits at taxpayers' expense". The Guardian. Retrieved May 14, 2015.

- ↑ "'Malingerer' Gets 90 Days Hard Labor". Military.com. 2009-09-02. Archived from the original on 2012-05-10. Retrieved 2014-09-04.

- ↑ "Perspectives on Paying the Federal Minimum Wage" (PDF). Prisoner Labor: 4. 1993.

- ↑ "Perspectives on Paying the Federal Minimum Wage" (PDF). Prisoner Labor: 2. 1993.

- ↑ Constituent Services Informational Handbook (PDF). Corrections ADC. 2013. p. 16. Retrieved May 14, 2015.

- ↑ The Criminal Law Act 1997, section 11(1)

- ↑ Roberts, Geoffrey (2008). Stalin's Wars: From World War to Cold War, 1939-1953. Yale University Press.

- 1 2 Overy, Richard (2004). The Dictators: Hitler's Germany, Stalin's Russia. W. W. Norton Company, Inc.

- ↑ "Gulag: Understanding the Magnitude of What Happened".

- ↑ Politics, economics and time bury memories of the Kazakh gulag, International Herald Tribune, 1 January 2007

- ↑ Archived 15 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "The National Archives | Heroes & Villains | Stalin & industrialisation | Background". Learningcurve.gov.uk. Retrieved 2013-09-06.

- ↑ "German POWs in Allied Hands | The World War II Multimedia Database". Worldwar2database.com. 2011-07-26. Retrieved 2013-09-06.

- ↑ Antony Beevor, Stalingrad

- ↑ "Gulag: A History Of The Soviet Camps, By Anne Applebaum". Arlindo-correia.org. Retrieved 2013-09-06.

- ↑ "Gulag - Infoplease". www.infoplease.com.

- ↑ Archived 22 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Merritt, Steven (2003-05-11). "The Other Killing Machine". New York Times. Retrieved 2013-09-06.

- ↑ "News - Latest breaking UK news". Telegraph. 2013-06-09. Retrieved 2013-09-06.

- ↑

- ↑ Anne Applebaum. Gulag: A History. ISBN 9781400034093.

- ↑ Guilbaud, Fabrice. "Working in Prison: Time as Experienced by Inmates-Workers". JSTOR 40731128.

- ↑ Simon, Frances (6 March 1999). "More to prison work than sewing mailbags". The Independent. London: Independent News and Media Ltd. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- ↑ Brown, Andrea (5 March 2006). "Colorado inmates: Making license plates since 1926". The Gazette (Colorado Springs, CO). Retrieved 7 December 2008.

- ↑ Cameron, David (24 May 2005). "A message from the PM". ONE3ONE Solutions. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- ↑ Wood, Phillip J. (2007-09-01). "Globalization and Prison Privatization: Why Are Most of the World’s For-Profit Adult Prisons to Be Found in the American South?". International Political Sociology. 1 (3): 222–239. ISSN 1749-5687. doi:10.1111/j.1749-5687.2007.00015.x.

- ↑ Malik, Shiv (9 August 2012). "Prison call centre plans revealed". Retrieved 10 August 2012.

External links

Further reading

- Douglas A. Blackmon. Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black People in America from the Civil War to World War II (2008)

- Matthew J. Mancini. One Dies, Get Another: Convict Leasing in the American South, 1866-1928 (1996)

- Alex Lichtenstein. Twice the Work of Free Labor: The Political Economy of Convict Labor in the New South (1996)

- David M. Oshinsky. "Worse than Slavery": Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice (1996).