Haplogroup R-M269

| Haplogroup R-M269 | |

|---|---|

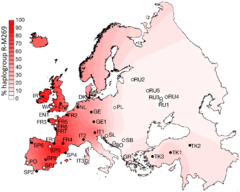

Projected spatial frequency distribution for haplogroup R-M269 in Europe.[1] | |

| Possible time of origin | 4,500–9,000 BP[2] |

| Possible place of origin | Neolithic Europe |

| Ancestor | R1b1a1 (R-L388) |

| Descendants | L23; L51/M412, L151/P310; Z2103 |

| Defining mutations | M269 |

Haplogroup R-M269, also known as R1b1a1a2, is a sub-clade of human Y-chromosome haplogroup R1b. It is of particular interest for the genetic history of Western Europe. It is defined by the presence of SNP marker M269. R-M269 has been the subject of intensive research; it was previously also known as R1b1a2 (2003 to 2005), R1b1c (2005 to 2008), and R1b1b2 (2008 to 2011)[3]

R-M269 is the most common European haplogroup, greatly increasing in frequency on an east to west gradient (its prevalence in Poland estimated at 22.7%, compared to Wales at 92.3%). It is carried by approximately 110 million European men (2010 estimate).[4] The age of the mutation M269 is estimated at roughly 4,000 to 10,000 years ago, and its sub-clades can be used to trace the Neolithic expansion into Europe as well founder-effects within European populations due to later (Bronze Age and Iron Age) migrations.[4]

Origin

An understanding of the origin of R-M269 is relevant for the question of population replacement in the Neolithic Revolution. R-M269 has formerly been dated to the Upper Paleolithic, [5] but by ca. 2010 it had become clear that it arises close to the beginning of the Neolithic Revolution, about 10,000 years ago.[6][7][8]

No clear consensus has been achieved as to whether it arose within Europe or in Western Asia. Balaresque et al. (2010) based on the pattern of Y-STR diversity argued for a single source in the Near East and introduction to Europe via Anatolia in the Neolithic Revolution. In this scenario, Mesolithic hunter-gatherers in Europe would have been nearly replaced by the incoming farmers. By contrast, Busby et al. (2012) could not confirm the results of Balaresque et al. (2010) and could not make credible estimates of the age of R-M269 based on Y-STR diversity.[9]

By contrast, the subclade R-P311 appears to have originated after the beginning of the Neolithic Revolution in Europe, and is substantially confined to Western Europe in modern populations. R-P311 is absent from Neolithic-era ancient DNA found in Western Europe, strongly suggesting that its current distribution is due to population movements within Europe taking place after the end of the Neolithic. The three major subclades of P311 are U106 (S21), L21 (M529, S145), and U152 (S28). These show a clear articulation within Western Europe, with centers in the Low Countries, the British Isles and the Alps, respectively.[10]

Distribution

European R1b is dominated by R-M269. It has been found at generally low frequencies throughout central Eurasia,[11] but with relatively high frequency among the Bashkirs of the Perm region (84.0%) and Baymaksky District (81.0%).[12] This marker is present in China and India at frequencies of less than one percent. The table below lists in more detail the frequencies of M269 in regions in Asia, Europe, and Africa.

The frequency is about 92% in Wales, 82% in Ireland, 70% in Scotland, 68% in Spain, 60% in France (76% in Normandy), about 60% in Portugal, 53% in Italy,[13] 45% in Eastern England, 50% in Germany, 50% in the Netherlands, 42% in Iceland, and 43% in Denmark. It is as high as 95% in parts of Ireland. It is also found in some areas of North Africa, where its frequency peaks at 10% in some parts of Algeria.[14] M269 has likewise been observed among 8% of the Herero in Namibia.[15]

The R-M269 subclade has been found in ancient Guanche (Bimbapes) fossils excavated in Punta Azul, El Hierro, Canary Islands, which are dated to the 10th century (~44%).[16]

M269* (xL23) is found at highest frequency in the central Balkans notably Kosovo with 7.9%, Macedonia 5.1% and Serbia 4.4%.[13] Kosovo is notable in having a high percentage of descendant L23* or L23(xM412) at 11.4% unlike most other areas with significant percentages of M269* and L23* except for Poland with 2.4% and 9.5% and the Bashkirs of southeast Bashkortostan with 2.4% and 32.2% respectively.[13] Notably this Bashkir population also has a high percentage of M269 sister branch M73 at 23.4%.[13] Five individuals out of 110 tested in the Ararat Valley, Armenia belonged to R1b1a2* and 36 to L23*, with none belonging to known subclades of L23.[17]

Trofimova et al. (2015) found a surprising high frequency of R1b-L23 (Z2105/2103) among the peoples of the Idel-Ural. 21 out of 58 (36.2%) of Burzyansky District Bashkirs, 11 out of 52 (21.2%) of Udmurts, 4 out of 50 (8%) of Komi, 4 out of 59 (6.8%) of Mordvins, 2 out of 53 (3.8%) of Besermyan and 1 out of 43 (2.3%) of Chuvash were R1b-L23 (Z2105/2103),[18] the type of R1b found in the recently analyzed Yamna remains of the Samara Oblast and Orenburg Oblast.[19]

Especially Western European R1b is dominated by specific sub-clades of R-M269 (with some small amounts of other types found in areas such as Sardinia[13][20]). Within Europe, R-M269 is dominated by R-M412, also known as R-L51, which according to Myres et al. (2010) is "virtually absent in the Near East, the Caucasus and West Asia." This Western European population is further divided between R-P312/S116 and R-U106/S21, which appear to spread from the western and eastern Rhine river basin respectively. Myres et al. note further that concerning its closest relatives, in R-L23*, it is "instructive" that these are often more than 10% of the population in the Caucasus, Turkey, and some southeast European and circum-Uralic populations. In Western Europe it is present but in generally much lower levels apart from "an instance of 27% in Switzerland's Upper Rhone Valley."[13] In addition, the sub-clade distribution map, Figure 1h titled "L11(xU106,S116)", in Myres et al. shows that R-P310/L11* (or as yet undefined subclades of R-P310/L11) occurs only in frequencies greater than 10% in Central England with surrounding areas of England and Wales having lower frequencies.[13] This R-P310/L11* is almost non-existent in the rest of Eurasia and North Africa with the exception of coastal lands fringing the western and southern Baltic (reaching 10% in Eastern Denmark and 6% in northern Poland) and in Eastern Switzerland and surrounds.[13]

| M269 (R1b1a1a2)[21] |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In 2009, DNA extracted from the femur bones of 6 skeletons in an early-medieval burial place in Ergolding (Bavaria, Germany) dated to around c. 670 yielded the following results: 4 were found to be haplogroup R1b with the closest matches in modern populations of Germany, Ireland and the USA while 2 were in Haplogroup G2a.[22]

Population studies which test for M269 have become more common in recent years, while in earlier studies men in this haplogroup are only visible in the data by extrapolation of what is likely. The following gives a summary of most of the studies which specifically tested for M269, showing its distribution (as a percentage of total population) in Europe, North Africa, the Middle East and Central Asia as far as China and Nepal.

| Country | Sampling | sample | R-M269 | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wales | National | 65 | 92.3% | Balaresque et al. (2009)[4] |

| Spain | Basques | 116 | 87.1% | Balaresque et al. (2009)[4] |

| Ireland | National | 796 | 85.4% | Moore et al. (2006)[23] |

| Spain | Catalonia | 80 | 81.3% | Balaresque et al. (2009)[4] |

| France | Ille-et-Vilaine | 82 | 80.5% | Balaresque et al. (2009)[4] |

| France | Haute-Garonne | 57 | 78.9% | Balaresque et al. (2009)[4] |

| England | Cornwall | 64 | 78.1% | Balaresque et al. (2009)[4] |

| France | Loire-Atlantique | 48 | 77.1% | Balaresque et al. (2009)[4] |

| Italy | Tuscany | 42 | 76.2% | Di Giacomo et al. (2003)[24] |

| France | Finistère | 75 | 76.0% | Balaresque et al. (2009)[4] |

| France | Basques | 61 | 75.4% | Balaresque et al. (2009)[4] |

| Italy | North East | 30 | 73.5% | Di Giacomo et al. (2003)[24] |

| Spain | East Andalucia | 95 | 72.0% | Balaresque et al. (2009)[4] |

| Spain | Castilla La Mancha | 63 | 72.0% | Balaresque et al. (2009)[4] |

| France | Vendée | 50 | 68.0% | Balaresque et al. (2009)[4] |

| Dominican Republic | National | 26 | 65.4% | Bryc et al. (2010)[25] |

| France | Baie de Somme | 43 | 62.8% | Balaresque et al. (2009)[4] |

| England | Leicestershire | 43 | 62.0% | Balaresque et al. (2009)[4] |

| Italy | North-East (Ladin) | 79 | 60.8% | Balaresque et al. (2009)[4] |

| Portugal | National | 657 | 59.9% | Beleza et al. (2006)[26] |

| Italy | Lombardy | 80 | 59.0% | Boattini et al. (2009)[27] |

| Spain | Galicia | 88 | 58.0% | Balaresque et al. (2009)[4] |

| Spain | West Andalucia | 72 | 55.0% | Balaresque et al. (2009)[4] |

| Portugal | South | 78 | 46.2% | Balaresque et al. (2009)[4] |

| Denmark | National | 56 | 42.9% | Balaresque et al. (2009)[4] |

| Netherlands | National | 84 | 42.0% | Balaresque et al. (2009)[4] |

| Armenia/Turkey | Ararat Valley | 41 | 37.3% | Herrera et al. (2012)[17] |

| Russia | Bashkirs | 471 | 34.40% | Lobov (2009)[12] |

| Italy | East Sicily | 246 | 34.14% | Tofanelli et al. (2015)[28] |

| Italy | West Sicily | 68 | 33.0% | Tofanelli et al. (2015)[28] |

| Germany | Bavaria | 80 | 32.3% | Balaresque et al. (2009)[4] |

| Turkey | Lake Van | 33 | 32.0% | Herrera et al. (2012) [17] |

| Armenia | Gardman | 30 | 31.3% | Herrera et al. (2012) [17] |

| Poland | National | 110 | 22.7% | Myres et al. (2007)[29] |

| Slovenia | National | 75 | 21.3% | Battaglia et al. (2008)[30] |

| Slovenia | National | 70 | 20.6% | Balaresque et al. (2009)[4] |

| Turkey | Central | 152 | 19.1% | Cinnioğlu et al. (2004)[31] |

| Republic of Macedonia | National | 64 | 18.8% | Battaglia et al. (2008)[30] |

| Crete | National | 193 | 17.0% | King et al. (2008)[32] |

| Italy | Sardinia | 930 | 17.0% | Contu et al. (2008)[33] |

| Turkey | Sasun | 16 | 15.4% | Herrera et al. (2012) [17] |

| Iran | North | 33 | 15.2% | Regueiro et al. (2006)[34] |

| Moldova | 268 | 14.6% | Varzari (2006)[35] | |

| Greece | National | 171 | 13.5% | King et al. (2008)[32] |

| Turkey | West | 163 | 13.5% | Cinnioğlu et al. (2004)[31] |

| Romania | National | 54 | 13.0% | Varzari (2006)[35] |

| Croatia | National | 89 | 12.4% | Battaglia et al. (2008)[30] |

| Turkey | East | 208 | 12.0% | Cinnioğlu et al. (2004)[31] |

| Algeria | Northwest (Oran area) | 102 | 11.8% | Robino et al. (2008)[36] |

| Russia | Roslavl (Smolensk Oblast) | 107 | 11.2% | Balanovsky et al. (2008)[37] |

| Iraq | National | 139 | 10.8% | Al-Zahery et al. (2003)[38] |

| Nepal | Newar | 66 | 10.60% | Gayden et al. (2007)[39] |

| Bulgaria | National | 808 | 10.5% | Karachanak et al. (2013)[40] |

| Serbia | National | 100 | 10.0% | Belaresque et al. (2009)[4] |

| Lebanon | National | 914 | 7.3% | Zalloua et al. (2008)[41] |

| Tunisia | Tunis | 139 | 7.2% | Adams et al. (2008)[42] |

| Algeria | Algiers, Tizi Ouzou | 46 | 6.5% | Adams et al. (2008)[42] |

| Bosnia-Herzegovina | Serbs | 81 | 6.2% | Marjanovic et al. (2005)[43] |

| Iran | South | 117 | 6.0% | Regueiro et al. (2006)[34] |

| Russia | Repyevka (Voronezh Oblast) | 96 | 5.2% | Balanovsky et al. (2008)[37] |

| UAE | 164 | 3.7% | Cadenas et al. (2007)[44] | |

| Bosnia-Herzegovina | Bosniaks | 85 | 3.5% | Marjanovic et al. (2005)[43] |

| Pakistan | 176 | 2.8% | Sengupta et al. (2006)[45] | |

| Russia | Belgorod | 143 | 2.8% | Balanovsky et al. (2008)[37] |

| Russia | Ostrov (Pskov Oblast) | 75 | 2.7% | Balanovsky et al. (2008)[37] |

| Russia | Pristen (Kursk Oblast) | 45 | 2.2% | Balanovsky et al. (2008)[37] |

| Bosnia-Herzegovina | Croats | 90 | 2.2% | Marjanovic et al. (2005)[43] |

| Qatar | 72 | 1.4% | Cadenas et al. (2007)[44] | |

| China | 128 | 0.8% | Sengupta et al. (2006)[45] | |

| India | various | 728 | 0.5% | Sengupta et al. (2006)[45] |

| Croatia | Osijek | 29 | 0.0% | Battaglia et al. (2008)[30] |

| Yemen | 62 | 0.0% | Cadenas et al. (2007)[44] | |

| Tibet | 156 | 0.0% | Gayden et al. (2007)[39] | |

| Nepal | Tamang | 45 | 0.0% | Gayden et al. (2007)[39] |

| Nepal | Kathmandu | 77 | 0.0% | Gayden et al. (2007)[39] |

| Japan | 23 | 0.0% | Sengupta et al. (2006)[45] |

Sub-clades

R1b1a1a2a (R-L23)

R-L23* (R1b1a1a2a*) is now most commonly found in Anatolia, the Caucasus and the Mediterranean .

R1b1a1a2a1 (R-L51)

R-L51* (R1b1a1a2a1*) is now concentrated in a geographical cluster centred on southern France and northern Italy.

R1b1a1a2a1a (R-L151)

R-L151 (L151/PF6542, CTS7650/FGC44/PF6544/S1164, L11, L52/PF6541, P310/PF6546/S129, P311/PF6545/S128) also known as R1b1a1a2a1, and its subclades, include most males with R1b in Western Europe.

R1b1a1a2a1a1 (R-U106)

This subclade is defined by the presence of the SNP U106, also known as S21 and M405.[6][46] It appears to represent over 25% of R1b in Europe.[6] In terms of percentage of total population, its epicenter is Friesland, where it makes up 44% of the population.[47] In terms of total population numbers, its epicenter is Central Europe, where it comprises 60% of R1 combined.[47]

| U106/S21 |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

While this sub-clade of R1b is frequently discussed amongst genetic genealogists, the following table represents the peer-reviewed findings published so far in the 2007 articles of Myres et al. and Sims et al.[29][46]

| Population | Sample size | R-M269 | R-U106 | R-U106-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria [29] | 22 | 27% | 23% | 0.0% |

| Central/South America [29] | 33 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Czech Republic [29] | 36 | 28% | 14% | 0.0% |

| Denmark [29] | 113 | 34% | 17% | 0.9% |

| Eastern Europe[29] | 44 | 5% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| England[29] | 138 | 57% | 20% | 1.4% |

| France[29] | 56 | 52% | 7% | 0.0% |

| Germany[29] | 332 | 43% | 19% | 1.8% |

| Ireland[29] | 102 | 80% | 6% | 0.0% |

| Italy[13] | 34 | 53% | 6% | 0.0% |

| Jordan[29] | 76 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Middle-East[29] | 43 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Netherlands[29] | 94 | 54% | 35% | 2.1% |

| Oceania[29] | 43 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Oman[29] | 29 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Pakistan[29] | 177 | 3% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Palestine[29] | 47 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Poland[29] | 110 | 23% | 8% | 0.0% |

| Russia[29] | 56 | 21% | 5.4% | 1.8% |

| Slovenia[29] | 105 | 17% | 4% | 0.0% |

| Switzerland[29] | 90 | 58% | 13% | 0.0% |

| Turkey[29] | 523 | 14% | 0.4% | 0.0% |

| Ukraine[29] | 32 | 25% | 9% | 0.0% |

| United States[29] | 58 | 5% | 5% | 0.0% |

| US (European) | 125 | 46% | 15% | 0.8% |

| US (Afroamerican) | 118 | 14% | 2.5% | 0.8% |

R1b1a1a2a1a2 (R-P312/S116)

Along with R-U106, R-P312 is one of the most common types of R1b1a2 (R-M269) in Europe. Also known as S116, it has been the subject of significant study concerning its sub-clades, and some of the ones recognized by the ISOGG tree as of December 27, 2015 are summarized in the following table.[6] Myres et al. described it distributing from the west of the Rhine basin.[13]

| P312 |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- R-M153 is defined by the presence of the marker M153. It has been found mostly in Basques and Gascons, among whom it represents a sizeable fraction of the Y-DNA pool,[42][48] though is also found occasionally among Iberians in general. The first time it was located (Bosch 2001[49]) it was described as H102 and included 7 Basques and one Andalusian.

- R-S228 This subclade is defined by the presence of the marker L176.2. It contains the following:

- R-SRY2627

- This subclade is defined by the presence of the marker M167, also known as SRY2627. The first author to test for this marker (long before current haplogroup nomenclature existed) was Hurles in 1999, who tested 1158 men in various populations.[50] He found it relatively common among Basques (13/117: 11%) and Catalans (7/32: 22%). Other occurrences were found among other French, British, Spaniards, Béarnais, and Germans.

- In 2000 Rosser et al., in a study which tested 3616 men in various populations[51] also tested for that same marker, naming the haplogroup Hg22, and again it was found mainly among Basques (19%), in lower frequencies among French (5%), Bavarians (3%), Spaniards (2%), Southern Portuguese (2%), and in single occurrences among Romanians, Slovenians, Dutch, Belgians and English.::In 2001 Bosch described this marker as H103, in 5 Basques and 5 Catalans.[49] Further regional studies have located it in significant amounts in Asturias, Cantabria and Galicia, as well as again among Basques.[49] Cases in the Azores have been reported. In 2008 two research papers by López-Parra[48] and Adams,[42] respectively, confirmed a strong association with all or most of the Pyrenees and Eastern Iberia.

- In a larger study of Portugal in 2006, with 657 men tested, Beleza et al. confirmed similar low levels in all the major regions, from 1.5%–3.5%.[26]

- R-L165 This subclade is defined by the presence of the marker S68, also known as L165. It is found in England, Scandinavia, and Scotland (in this country it is mostly found in the Northern Isles and Outer Hebrides). It has been suggested, therefore, that it arrived in the British Isles with Vikings.[52]

R-U152 is defined by the presence of the marker U152, also called S28.[6] Its discovery was announced in 2005 by EthnoAncestry[53] and subsequently identified independently by Sims et al. (2007).[46] Myres et al. report this clade "is most frequent (20–44%) in Switzerland, Italy, France and Western Poland, with additional instances exceeding 15% in some regions of England and Germany."[29] Similarly Cruciani et al. (2010)[54] reported frequency peaks in Northern Italy and France. Out of a sample of 135 men in Tyrol, Austria, 9 tested positive for U152/S28.[55] Far removed from this apparent core area, Myres et al. also mention a sub-population in north Bashkortostan, where 71% of 70 men tested belong to R-U152. They propose this to be the result of an isolated founder effect.[13] King et al. (2014) reported four living descendants of Henry Somerset, 5th Duke of Beaufort in the male line tested positive for U-152.[56]

R-L21 is defined by the presence of the marker L21, also referred to as M529 and S145.[6] Myres et al. report it is most common in England and Ireland (25–50% of the whole male population).[13] Known sub-clades include the following:-

- R-M222 This subclade within R-L21 is defined by the presence of the marker M222. It is particularly associated with male lines which are Gaelic (Irish or Scottish), but especially northern Irish. In this case, the relatively high frequency of this specific subclade among the population of certain counties in northwestern Ireland may be due to positive social selection, as it is suggested to have been the Y-chromosome haplogroup of the Uí Néill dynastic kindred of ancient Ireland.[23] However, it is not restricted to the Uí Néill as it is associated with the closely related Connachta dynasties, the Uí Briúin and Uí Fiachrach.[57] M222 is also found as a substantial proportion of the population of Scotland which may indicate substantial settlement from northern Ireland or at least links to it.[23][58] Those areas settled by large numbers of Irish and Scottish emigrants such as North America have a substantial percentage of M222.[23]

- R-L159.2 This subclade within R-L21 is defined by the presence of the marker L159 and is known as L159.2 because of a parallel mutation that exists inside haplogroup I2a1 (L159.1). L159.2 appears to be associated with the Kings of Leinster and Diarmait Mac Murchada; Irish Gaels belonging to the Laigin. It can be found in the coastal areas of the Irish Sea including the Isle of Man and the Hebrides, as well as Norway, western and southern Scotland, northern and southern England, northwest France, and northern Denmark.[59]

- R-L193 This subclade within R-L21 is defined by the presence of the marker L193. Many surnames with this marker are associated geographically with the western "Border Region" of Scotland. A few other surnames have a Highland association. R-L193 is a relatively young subclade likely born within the last 2000 years.

- R-L226 This subclade within R-L21 is defined by the presence of the marker L226, also known as S168. Commonly referred to as Irish Type III, it is concentrated in central western Ireland and associated with the Dál gCais kindred.[60]

- R-DF21 This subclade within R-L21 is defined by the presence of the marker DF21 aka S192. It makes up about 10% of all L21 men and is c.3000 years old.[61]

See also

References

- ↑ Balaresque et al. (2010), figure 1B: "Geographical distribution of haplogroup frequency of hgR1b1b2, shown as an interpolated spatial frequency surface. Filled circles indicate populations for which microsatellite data and TMRCA estimates are available. Unfilled circles indicate populations included to illustrate R1b1b2 frequency only. Population codes are defined in Table 1."

- ↑ "Mean estimates for individual populations vary (Table 2), but the oldest value is in Central Turkey (7,989 y [95% confidence interval (CI): 5,661–11,014]), and the youngest in Cornwall (5,460 y [3,764–7,777]). The mean estimate for the entire dataset is 6,512 y (95% CI: 4,577–9,063 years), with a growth rate of 1.95% (1.02%–3.30%). Thus, we see clear evidence of rapid expansion, which cannot have begun before the Neolithic period." Balaresque et al. (2010).

- ↑ dates according to the ISOGG trees for each respective year.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Balaresque, Patricia; Bowden, Georgina R.; Adams, Susan M.; Leung, Ho-Yee; King, Turi E.; et al. (2010). Penny, David, ed. "A Predominantly Neolithic Origin for European Paternal Lineages". PLOS Biology. Public Library of Science. 8 (1): e1000285. PMC 2799514

. PMID 20087410. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000285.

. PMID 20087410. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000285. - ↑ Semino, O; Passarino, G; Oefner, PJ; Lin, AA; Arbuzova, S; Beckman, LE; De Benedictis, G; Francalacci, P; et al. (2000). "The genetic legacy of Paleolithic Homo sapiens sapiens in extant Europeans: a Y chromosome perspective". Science. 290 (5494): 1155–9. PMID 11073453. doi:10.1126/science.290.5494.1155.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 International Society of Genetic Genealogy (ISOGG) – Y-DNA Haplogroup R and its Subclades

- ↑ B. Arredi; E. S. Poloni; C. Tyler-Smith (2007). "The peopling of Europe". In Crawford, Michael H. Anthropological genetics: theory, methods and applications. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 394. ISBN 0-521-54697-4.

- ↑ Cruciani; Trombetta, Beniamino; Antonelli, Cheyenne; Pascone, Roberto; Valesini, Guido; Scalzi, Valentina; Vona, Giuseppe; Melegh, Bela; et al. (2010). "Strong intra- and inter-continental differentiation revealed by Y chromosome SNPs M269, U106 and U152". Forensic Science International: Genetics. 5 (3): e49. PMID 20732840. doi:10.1016/j.fsigen.2010.07.006.

- ↑ Balaresque, P. et al., "A Predominantly Neolithic Origin for European Paternal Lineages", PLOS (2010), doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1000285. Busby, G.B. et al., "The peopling of Europe and the cautionary tale of Y chromosome lineage R-M269", Proc Biol Sci. 2012 Mar 7;279(1730):884-92. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.1044.

- ↑ Michael Hammer, "Origins of R-M269 Diversity in Europe", FamilyTreeDNA 9th Annual Conference (2013).

- ↑ Peter A. Underhill, Peidong Shen, Alice A. Lin et al., "Y chromosome sequence variation and the history of human populations", Nature Genetics, Volume 26, November 2000

- 1 2 A. S. Lobov et al. (2009), "Structure of the Gene Pool of Bashkir Subpopulations" (original text in Russian)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Myres, Natalie; Rootsi, Siiri; Lin, Alice A; Järve, Mari; King, Roy J; Kutuev, Ildus; Cabrera, Vicente M; Khusnutdinova, Elza K; et al. (2010). "A major Y-chromosome haplogroup R1b Holocene effect in Central and Western Europe". European Journal of Human Genetics. 19 (1): 95–101. PMC 3039512

. PMID 20736979. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2010.146.

. PMID 20736979. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2010.146. - ↑ Analysis of Y-chromosomal SNP haplogroups and STR haplotypes in an Algerian population sample

- ↑ Wood, ET; Stover, DA; Ehret, C; Destro-Bisol, G; Spedini, G; Mcleod, H; Louie, L; Bamshad, M; et al. (2005). "Contrasting patterns of Y chromosome and mtDNA variation in Africa: evidence for sex-biased demographic processes" (PDF). European Journal of Human Genetics. 13 (7): 867–76. PMID 15856073. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201408. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 26, 2008.

- ↑ Ordóñez, A. C., Fregel, R., Trujillo-Mederos, A., Hervella, M., de-la-Rúa, C., & Arnay-de-la-Rosa, M. (2017). "Genetic studies on the prehispanic population buried in Punta Azul cave (El Hierro, Canary Islands)". Journal of Archaeological Science. 78: 20–28. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2016.11.004. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kristian, J Herrera; Lowery, Robert K; Hadden, Laura. "Haplotype diversity, variance and time estimations for Haplogroup R1b". European Journal of Human Genetics. 20 (3): Table 3. PMC 3286660

. PMID 22085901. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2011.192.

. PMID 22085901. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2011.192. - ↑ Трофимова Натал'я Вадимовна (Feb. 2015), "Изменчивость Митохондриальной ДНК и Y-Хромосомы в Популяциях Волго-Уральского Региона" ("Mitochondrial DNA variation and the Y-chromosome in the population of the Volga-Ural Region"). Автореферат. диссертации на соискание ученой степени кандидата биологических наук. Уфа – 2015.

- ↑ Haak, Wolfgang; Lazaridis, Iosif (February 10, 2015). "Massive migration from the steppe is a source for Indo-European languages in Europe". bioRxiv 013433

.

. - ↑ Morelli, Laura; Contu, Daniela; Santoni, Federico; Whalen, Michael B.; Francalacci, Paolo; Cucca, Francesco (2010). Lalueza-Fox, Carles, ed. "A Comparison of Y-Chromosome Variation in Sardinia and Anatolia Is More Consistent with Cultural Rather than Demic Diffusion of Agriculture". PLoS ONE. 5 (4): e10419. PMC 2861676

. PMID 20454687. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010419.

. PMID 20454687. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010419. - ↑ ISOGG tree as of 2017 (isogg.org)

- ↑ Vanek, Daniel; Saskovat and Koch (June 2009). "Kinship and Y-Chromosome Analysis of 7th Century Human Remains: Novel DNA Extraction and Typing Procedure for Ancient Material". Croatian Medical Journal. 3. 50 (3): 286–295. PMC 2702742

. PMID 19480023. doi:10.3325/cmj.2009.50.286.

. PMID 19480023. doi:10.3325/cmj.2009.50.286. - 1 2 3 4 Moore; McEvoy, B; Cape, E; Simms, K; Bradley, DG; et al. (2006). "A Y-Chromosome Signature of Hegemony in Gaelic Ireland". American Journal of Human Genetics. 78 (2): 334–8. PMC 1380239

. PMID 16358217. doi:10.1086/500055.

. PMID 16358217. doi:10.1086/500055. - 1 2 "Clinal patterns of human Y chromosomal diversity in continental Italy and Greece are dominated by drift and founder effects, Di Giacomo et al. (2003) (PDF)" (PDF).

- ↑ Bryc, Katarzyna et al. (May 2010). "Genome-wide patterns of population structure and admixture among Hispanic/Latino populations". PNAS 107: 5, 7–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.0914618107. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- 1 2 Beleza, S; Gusmão, L; Lopes, A; Alves, C; Gomes, I; Giouzeli, M; Calafell, F; Carracedo, A; et al. (2006). "Micro-phylogeographic and demographic history of Portuguese male lineages". Annals of Human Genetics. 70 (Pt 2): 181–94. PMID 16626329. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.00221.x.

395/657

- ↑ Boattini, A; Martinez-Cruz, B; Sarno, S; Harmant, C; Useli, A; Sanz, P; Yang-Yao, D; Manry, J; Ciani, G; Luiselli, D; Quintana-Murci, L; Comas, D; Pettener, D. "Uniparental Markers in Italy Reveal a Sex-Biased Genetic Structure and Different Historical Strata". PLoS ONE. 8: e65441. PMC 3666984

. PMID 23734255. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0065441.

. PMID 23734255. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0065441. - 1 2 Tofanelli, S; Brisighelli, F; Anagnostou, P; Busby, GB; Ferri, G; Thomas, MG; Taglioli, L; Rudan, I; Zemunik, T; Hayward, C; Bolnick, D; Romano, V; Cali, F; Luiselli, D; Shepherd, GB; Tusa, S; Facella, A; Capelli, C. "The Greeks in the West: genetic signatures of the Hellenic colonisation in southern Italy and Sicily, Tofanelli et al". Eur J Hum Genet. 24: 429–36. PMC 4757772

. PMID 26173964. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2015.124.

. PMID 26173964. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2015.124. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 Myres, NM; Ekins, JE; Lin, AA; Cavalli-Sforza, LL; Woodward, SR; Underhill, PA (2007). "Y-chromosome Short Tandem Repeat DYS458.2 Non-consensus Alleles Occur Independently in Both Binary Haplogroups J1-M267 and R1b3-M405". Croatian medical journal. 48 (4): 450–9. PMC 2080563

. PMID 17696299.

. PMID 17696299. - 1 2 3 4 Battaglia, V; Fornarino, S; Al-Zahery, N; Olivieri, A; Pala, M; Myres, NM; King, RJ; Rootsi, S; et al. (2009). "Y-chromosomal evidence of the cultural diffusion of agriculture in southeast Europe". European Journal of Human Genetics. 17 (6): 820–30. PMC 2947100

. PMID 19107149. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2008.249.

. PMID 19107149. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2008.249. - 1 2 3 Cinnioğlu, C; King, R; Kivisild, T; Kalfoğlu, E; Atasoy, S; Cavalleri, GL; Lillie, AS; Roseman, CC; et al. (2004). "Excavating Y-chromosome haplotype strata in Anatolia" (PDF). Human Genetics. 114 (2): 127–48. PMID 14586639. doi:10.1007/s00439-003-1031-4.

- 1 2 King, RJ; Ozcan, SS; Carter, T; Kalfoğlu, E; Atasoy, S; Triantaphyllidis, C; Kouvatsi, A; Lin, AA; et al. (2008). "Differential Y-chromosome Anatolian influences on the Greek and Cretan Neolithic". Annals of Human Genetics. 72 (Pt 2): 205–14. PMID 18269686. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2007.00414.x.

- ↑ Contu, D; Morelli, L; Santoni, F; Foster, JW; Francalacci, P; Cucca, F; Hawks, John (2008). Hawks, John, ed. "Y-Chromosome Based Evidence for Pre-Neolithic Origin of the Genetically Homogeneous but Diverse Sardinian Population: Inference for Association Scans". PLoS ONE. 3 (1): e1430. PMC 2174525

. PMID 18183308. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001430.

. PMID 18183308. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001430. 174/930

- 1 2 Regueiro, M; Cadenas, AM; Gayden, T; Underhill, PA; Herrera, RJ; et al. (2006). "Iran: Tricontinental Nexus for Y-Chromosome Driven Migration" (PDF). Hum Hered. 61 (3): 132–143. PMID 16770078. doi:10.1159/000093774. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 21, 2011.

- 1 2 Varzari, Alexander (2006). "Population History of the Dniester-Carpathians: Evidence from Alu Insertion and Y-Chromosome Polymorphisms" (PDF). Dissertation der Fakultät für Biologie der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München.

- ↑ Robino; Crobu, F; Di Gaetano, C; Bekada, A; Benhamamouch, S; Cerutti, N; Piazza, A; Inturri, S; et al. (2008). "Analysis of Y-chromosomal SNP haplogroups and STR haplotypes in an Algerian population sample". Journal International Journal of Legal Medicine. 122 (3): 251–5. PMID 17909833. doi:10.1007/s00414-007-0203-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Balanovsky, O; Rootsi, S; Pshenichnov, A; Kivisild, T; Churnosov, M; Evseeva, I; Pocheshkhova, E; Boldyreva, M; et al. (2008). "Two Sources of the Russian Patrilineal Heritage in Their Eurasian Context". AJHG. 82 (1): 236–250. PMC 2253976

. PMID 18179905. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.09.019.

. PMID 18179905. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.09.019. - ↑ Al-Zahery, N; Semino, O; Benuzzi, G; Magri, C; Passarino, G; Torroni, A; Santachiara-Benerecetti, AS (2003). "Y-chromosome and mtDNA polymorphisms in Iraq, a crossroad of the early human dispersal and of post-Neolithic migrations" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics & Evolution. 28 (3): 458–72. PMID 12927131. doi:10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00039-3.

16/139

- 1 2 3 4 Gayden, T; Cadenas, AM; Regueiro, M; Singh, NB; Zhivotovsky, LA; Underhill, PA; Cavalli-Sforza, LL; Herrera, RJ (2007). "The Himalayas as a Directional Barrier to Gene Flow". American Journal of Human Genetics. 80 (5): 884–94. PMC 1852741

. PMID 17436243. doi:10.1086/516757.

. PMID 17436243. doi:10.1086/516757. - ↑ Karachanak S, Grugni V, Fornarino S, et al. (2013). "Y-chromosome diversity in modern Bulgarians: new clues about their ancestry". PLoS ONE. 8 (3): e56779. PMC 3590186

. PMID 23483890. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0056779.

. PMID 23483890. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0056779. - ↑ Zalloua, PA; Xue, Y; Khalife, J; Makhoul, N; Debiane, L; Platt, DE; Royyuru, AK; Herrera, RJ; Hernanz, DF; et al. (2008). "Y-Chromosomal Diversity in Lebanon Is Structured by Recent Historical Events". American Journal of Human Genetics. 82 (4): 873–82. PMC 2427286

. PMID 18374297. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.01.020.

. PMID 18374297. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.01.020. - 1 2 3 4 Adams, SM; Bosch, E; Balaresque, PL; Ballereau, SJ; Lee, AC; Arroyo, E; López-Parra, AM; Aler, M; et al. (2008). "The Genetic Legacy of Religious Diversity and Intolerance: Paternal Lineages of Christians, Jews, and Muslims in the Iberian Peninsula". American Journal of Human Genetics. 83 (6): 725–36. PMC 2668061

. PMID 19061982. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.11.007.

. PMID 19061982. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.11.007. - 1 2 3 Marjanovic D, Fornarino S, Montagna S, et al. (November 2005). "The peopling of modern Bosnia-Herzegovina: Y-chromosome haplogroups in the three main ethnic groups". Annals of Human Genetics. 69 (Pt 6): 757–63. PMID 16266413. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.00190.x.

- 1 2 3 Cadenas; Zhivotovsky, LA; Cavalli-Sforza, LL; Underhill, PA; Herrera, RJ; et al. (2007). "Y-chromosome diversity characterizes the Gulf of Oman". European Journal of Human Genetics. 16 (3): 1–13. PMID 17928816. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201934.

- 1 2 3 4 Sengupta, S; Zhivotovsky, LA; King, R; Mehdi, SQ; Edmonds, CA; Chow, CE; Lin, AA; Mitra, M; et al. (February 2006). "Polarity and Temporality of High-Resolution Y-Chromosome Distributions in India Identify Both Indigenous and Exogenous Expansions and Reveal Minor Genetic Influence of Central Asian Pastoralists". American Journal of Human Genetics. 78 (2): 202–21. PMC 1380230

. PMID 16400607. doi:10.1086/499411.

. PMID 16400607. doi:10.1086/499411. 8/176 R-M73 and 5/176 R-M269 for a total of 13/176 R1b in Pakistan and 4/728 R-M269 in India

- 1 2 3 Sims, LM; Garvey, D; Ballantyne, J (2007). "Sub-populations within the major European and African derived haplogroups R1b3 and E3a are differentiated by previously phylogenetically undefined Y-SNPs" (PDF). Human Mutation. 28 (1): 97. PMID 17154278. doi:10.1002/humu.9469.

- 1 2 https://gap.familytreedna.com/media/docs/2013/Hammer_M269_Diversity_in_Europe.pdf

- 1 2 López-Parra, AM; Gusmão, L; Tavares, L; Baeza, C; Amorim, A; Mesa, MS; Prata, MJ; Arroyo-Pardo, E (2009). "In search of the pre- and post-neolithic genetic substrates in Iberia: evidence from Y-chromosome in Pyrenean populations". Annals of Human Genetics. 73 (1): 42–53. PMID 18803634. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2008.00478.x.

- 1 2 3 Bosch, E; Calafell, F; Comas, D; Oefner, PJ; Underhill, PA; Bertranpetit, J (2001). "High-Resolution Analysis of Human Y-Chromosome Variation Shows a Sharp Discontinuity and Limited Gene Flow between Northwestern Africa and the Iberian Peninsula". American Journal of Human Genetics. 68 (4): 1019–29. PMC 1275654

. PMID 11254456. doi:10.1086/319521.

. PMID 11254456. doi:10.1086/319521. - ↑ Hurles, ME; Veitia, R; Arroyo, E; Armenteros, M; Bertranpetit, J; Pérez-Lezaun, A; Bosch, E; Shlumukova, M; et al. (1999). "Recent Male-Mediated Gene Flow over a Linguistic Barrier in Iberia, Suggested by Analysis of a Y-Chromosomal DNA Polymorphism". American Journal of Human Genetics. 65 (5): 1437–48. PMC 1288297

. PMID 10521311. doi:10.1086/302617.

. PMID 10521311. doi:10.1086/302617. - ↑ Rosser, ZH; Zerjal, T; Hurles, ME; Adojaan, M; Alavantic, D; Amorim, A; Amos, W; Armenteros, M; et al. (2000). "Y-Chromosomal Diversity in Europe Is Clinal and Influenced Primarily by Geography, Rather than by Language". American Journal of Human Genetics. 67 (6): 1526–43. PMC 1287948

. PMID 11078479. doi:10.1086/316890.

. PMID 11078479. doi:10.1086/316890. - ↑ Moffat, Alistair; Wilson, James F. (2011). The Scots: a genetic journey. Birlinn. pp. 181–182, 192. ISBN 978-0-85790-020-3

- ↑ http://ethnoancestry.com/R1b.html%5B%5D

- ↑ Cruciani, Fulvio; et al. (June 2011). "Strong intra- and inter-continental differentiation revealed by Y chromosome SNPs M269, U106 and U152". Forensic Science International: Genetics. 5 (3): 49–52. PMID 20732840. doi:10.1016/j.fsigen.2010.07.006.

- ↑ Niederstätter, Harald; Berger, Burkhard; Erhart, Daniel; Parson, Walther (August 2008). "Recently introduced Y-SNPs improve the resolution within Y-chromosome haplogroup R1b in a central European population sample (Tyrol, Austria)". Forensic Science International: Genetics Supplement Series. 1: 226–227. doi:10.1016/j.fsigss.2007.10.158. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ↑ Henry Somerset was in turn descended in the patrilineal line from John of Gaunt (1340–1399), a son of King Edward III (1312–1377). In the context of the analysis of the remains of Richard III, which proved to belong to haplogroup G2, the possibility of a false-paternity event, most likely between Edward III and Henry Somerset, was discussed; possibly confirming rumors to the effect that John of Gaunt was illegitimate (Jonathan Sumption, Divided Houses: The Hundred Years War III, 2009, p. 274).

King, Turi E.; et al. (2 December 2014). "Identification of the remains of King Richard III". Nature Communications. 5 (5631). PMC 4268703

. PMID 25463651. doi:10.1038/ncomms6631. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

"Y-chromosome haplotypes from male-line relatives and the remains do not match, which could be attributed to a false-paternity event occurring in any of the intervening generations."

. PMID 25463651. doi:10.1038/ncomms6631. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

"Y-chromosome haplotypes from male-line relatives and the remains do not match, which could be attributed to a false-paternity event occurring in any of the intervening generations." - ↑ O'Neill; McLaughlin (2006). "Insights Into the O'Neills of Ireland from DNA Testing". Journal of Genetic Genealogy

- ↑ Campbell, Kevin D. (2007). "Geographic Patterns of Haplogroup R1b in the British Isles" (PDF). Journal of Genetic Genealogy. 3: 1–13.

- ↑ "R-L159 Project Goals"

- ↑ Wright (2009). "A Set of Distinctive Marker Values Defines a Y-STR Signature for Gaelic Dalcassian Families". Journal of Genetic Genealogy.

- ↑ "R-DF21 and Subclades Project".