Macro-haplogroup L (mtDNA)

| Haplogroup L | |

|---|---|

| Time of origin | 151,600–233,600 YBP[1] |

| Place of origin | Eastern Africa[2] |

| Descendants | L0, L1-6 |

In human mitochondrial genetics, L is the mitochondrial DNA macro-haplogroup that is at the root of the human mtDNA phylogenetic tree. As such, it represents the most ancestral mitochondrial lineage of all currently living modern humans.

Macro-haplogroup L's origin is connected with Mitochondrial Eve, and thus, is believed to suggest an ultimate African origin of modern humans. Its major sub-clades include L0, L1, L2, L3, L4, L5 and L6, with all non-Africans exclusively descended from just haplogroup L3.

Haplogroup L3 descendants notwithstanding, the designation "haplogroup L" is typically used to designate the family of mtDNA clades that are most frequently found in Sub-Saharan Africa. However, all non-African haplogroups coalesce onto either haplogroup M or haplogroup N, and both these macrohaplogroups are simply sub-branches of haplogroup L3. Consequently, L in its broadest definition is really a paragroup containing all of modern humanity, and all human mitochondrial DNA from around the world are subclades of haplogroup L. Haplogroups M and N are sometimes referred to as haplogroups L3M and L3N respectively. Mitochondrial Eve is defined as the female human ancestor who is the most recent common ancestor of the most deep-rooted lineages of humanity: haplogroups L, L0 and L1-6.

| Haplogroup L phylogeny | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Origin

Studies of human mitochondrial (mt) DNA genomes demonstrate that the root of the human phylogenetic tree occurs in East Africa. The data suggest that Tanzanians have high genetic diversity and possess ancient mtDNA haplogroups, some of which are either rare or absent in other regions of Africa. A large and diverse human population has persisted in eastern Africa and that region may have been an ancient source of dispersion of modern humans both within and outside of Africa.[2]

Mitochondrial Eve is the ancestor of this macro-haplogroup and she is estimated to have lived approximately 190,000 years ago.[1]

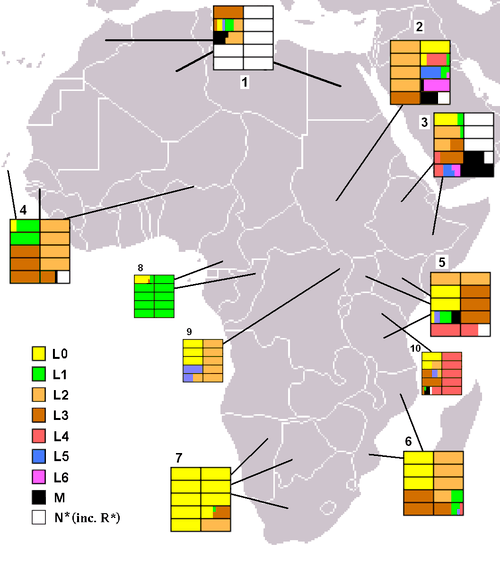

Distribution

Putting aside its sub-branches, haplogroups M and N, L haplogroups are predominant all over sub-Saharan Africa; L is at 96-100%, apart from spreading areas of Afroasiatic languages, where it is lower. Low frequencies are in North Africa, Arabian Peninsula, Middle East and Europe.

Sub-Saharan Africa

With the exception of a number of lineages that returned to Africa from Eurasia after the out of Africa migration theory, all Sub-Saharan African lineages belong to haplogroup L. The "back-to-Africa" haplogroups including U6, X1 and possibly M1 have returned to Africa possibly as far back as 45,000 years ago.[3] Haplogroup H, which is common among Berbers, is also believed to have entered Africa from Europe during the post-glacial expansion.[4]

The mutations that are used to identify the basal lineages of haplogroup L, are ancient and may be 150,000 years old. The deep time depth of these lineages entails that substructure of this haplogroup within Africa is complex and, at present, poorly understood.[5] The first split within haplogroup L occurred 140-200kya, with the mutations that define macrohaplogroups L0 and L1-6. These two haplogroups are found throughout Africa at varying frequencies and thus exhibit an entangled pattern of mtDNA variation. However the distribution of some subclades of haplogroup L is structured around geographic or ethnic units. For example, the deepest clades of haplogroup L0, L0d and L0k are almost exclusively restricted to the Khoisan of southern Africa. L0d has also been detected among the Sandawe of Tanzania, which suggests an ancient connection between the Khoisan and East African populations.[6]

North Africa

Haplogroup L is also found at moderate frequencies in North Africa. For example, the various Berber populations have frequencies of haplogroup L lineages that range from 3% to 45%.[15][16] Haplogroup L has also been found at a small frequency of 2.2% in North African Jews from Morocco, Tunisia and Libya. Frequency was the highest in Libyan Jews 3.6%.[17] Moroccan Arabs have more elevated SSA maternal admixture at around 21% to 36% Via L-mtDNA sequences, Highest frequencies of L-mtDNA is reported to Moroccan Arabs of The Surrounding area of El jadida at 36% and this admixture is largely ascribed to the trans-Saharan slave trade.[18]

West Asia

Haplogroup L is also found in West Asia at low to moderate frequencies, most notably in Yemen where frequencies as high as 60% have been reported.[19] It is also found at 15.50% in Bedouins from Israel, 13.68% in Palestinians, 12.55% in Jordania, 9.48% in Iraq, 9.15% in Syria, 7.5% in the Hazara of Afghanistan, 6.66% in Saudi Arabia, 2.84% in Lebanon, 2.60% in Druzes from Israel, 2.44% in Kurds and 1.76% in Turks.[20][21] Overall the Arab slave trade and expansion of foreign empires that encapsulated Saudi Arabia were linked to the negligible presence of haplogroup L in the Saudi Arabian gene pool.[22]

Europe

In Europe, haplogroup L is found at low frequencies, typically less than 1% with the exception of Iberia (Spain and Portugal) where regional frequencies as high as 18.2% have been reported and some regions of Italy where frequencies between 2 and 3% have been found.

Overall frequency in Iberia is higher in Portugal than in Spain where frequencies are only high in the south and west of the country. Increasing frequencies are observed for Galicia (3.26%) and northern Portugal (3.21%), through the center (5.02%) and to the south of Portugal (11.38%).[23] Relatively high frequencies of 7.40% and 8.30% were also reported respectively in South Spain, in the present population of Huelva and Priego de Cordoba by Casas et al. 2006.[24] Significant frequencies were also found in the Autonomous regions of Portugal, with L haplogroups constituting about 13% of the lineages in Madeira and 3.4% in the Azores. In the Spanish archipelago of Canary Islands, frequencies have been reported at 6.6%.[25] According to some researchers L lineages in Iberia are associated to Islamic invasions, while for others it may be due to more ancient processes as well as more recent ones through the introduction of these lineages by means of the modern slave trade. The highest frequency (18.2%) of Sub-Saharan lineages found so far in Europe were observed by Alvarez et al. 2010 in the comarca of Sayago in Spain and in Alcacer do Sal in Portugal.[26][27]

In Italy, Haplogroup L lineages are present in some regions at frequencies between 2 and 3% in Latium (2.90%), parts of Tuscany,[21] Basilicata and Sicily.[28]

The Americas

Haplogroup L lineages are found in the African diaspora of the Americas as well as indigenous Americans. Haplogroup L lineages are predominant among African Americans, Afro-Caribbeans and Afro-Latin-Americans. In Brazil, Pena et al. report that 85% of self-identified Afro-Brazilians have Haplogroup L mtDNA sequences.[29] Haplogroup L lineages are also found at moderate frequencies in self-identified White Brazilians. Alves Silva reports that 28% of a sample of White Brazilians belong to haplogroup L.[30] In Argentina, a minor contribution of African lineages was observed throughout the country.[31] Haplogroup L lineages were also reported at 8% in Colombia,[32] and at 4.50% in North-Central Mexico.[33] In North America, haplogroup L lineages were reported at a frequency of 0.90% in White Americans of European ancestry.[34]

Haplogroup L Frequencies (> 1%)

| Region | Population or Country | Number tested | Reference | % |

| East Africa | Somalis | 26 | Watson et al. (1997) | 50.00% |

| East Africa | Sudan | 112 | Afonso et al. (2008) | 72.50% |

| East Africa | Ethiopia | 270 | Kivisild et al. (2004) | 52.20% |

| North Africa | Libya (Jews) | 83 | Behar et al. (2008) | 3.60% |

| North Africa | Tunisia (Jews) | 37 | Behar et al. (2008) | 2.20% |

| North Africa | Morocco (Jews) | 149 | Behar et al. (2008) | 1.34% |

| North Africa | Tunisia | 64 | Turchi et al. (2009) | 48.40% |

| North Africa | Tunisia (Takrouna) | 33 | Frigi et al. (2006) | 3.03% |

| North Africa | Tunisia (Zriba) | 50 | Turchi et al. (2009) | 8.00% |

| North Africa | Morocco | 56 | Turchi et al. (2009) | 26.80% |

| North Africa | Morocco (Berbers) | 64 | Turchi et al. (2009) | 3.20% |

| North Africa | Algeria (Mozabites) | 85 | Turchi et al. (2009) | 12.90% |

| North Africa | Algeria | 47 | Turchi et al. (2009) | 20.70% |

| Europe | Italy (Latium) | 138 | Achilli et al. (2007) | 2.90% |

| Europe | Italy (Volterra) | 114 | Achilli et al. (2007) | 2.60% |

| Europe | Italy (Basilicata) | 92 | Ottoni et al. (2009) | 2.20% |

| Europe | Italy (Sicily) | 154 | Ottoni et al. (2009) | 2.00% |

| Europe | Malta | 132 | Caruana et al. (2016) | 15.90%[35] |

| Europe | Spain | 312 | Alvarez et al. (2007) | 2.90% |

| Europe | Spain (Galicia) | 92 | Pereira et al. (2005) | 3.30% |

| Europe | Spain (North East) | 118 | Pereira et al. (2005) | 2.54% |

| Europe | Spain (Priego de Cordoba) | 108 | Casas et al. (2006) | 8.30% |

| Europe | Spain (Zamora) | 214 | Alvarez et al. (2010) | 4.70% |

| Europe | Spain (Sayago) | 33 | Alvarez et al. (2010) | 18.18% |

| Europe | Spain (Catalonia) | 101 | Alvarez-Iglesias et al. (2009) | 2.97% |

| Europe | South Iberia | 310 | Casas et al. (2006) | 7.40% |

| Europe | Spain (Canaries) | 300 | Brehm et al. (2003) | 6.60% |

| Europe | Spain (Balearic Islands) | 231 | Picornell et al. (2005) | 2.20% |

| Europe | Spain (Andalusia) | 1004 | Barral-Arca et al. (2016) | 2.6% |

| Europe | Spain (Castilla y Leon) | 428 | Barral-Arca et al. (2016) | 2.1% |

| Europe | Spain (Aragón) | 70 | Barral-Arca et al. (2016) | 4.3% |

| Europe | Spain (Asturias) | 99 | Barral-Arca et al. (2016) | 4.0% |

| Europe | Spain (Galicia) | 98 | Barral-Arca et al. (2016) | 2.0% |

| Europe | Spain (Madrid) | 178 | Barral-Arca et al. (2016) | 1.70% |

| Europe | Spain (Castilla-La Mancha) | 207 | Barral-Arca et al. (2016) | 1.40% |

| Europe | Spain (Extremadura) | 87 | Barral-Arca et al. (2016) | 1.10% |

| Europe | Spain (Huelva) | 280 | Hernández et al. (2015) | 3.93% |

| Europe | Spain (Granada) | 470 | Hernández et al. (2015) | 1.49% |

| Europe | Portugal | 594 | Achilli et al. (2007) | 6.90% |

| Europe | Portugal (North) | 188 | Achilli et al. (2007) | 3.19% |

| Europe | Portugal (Central) | 203 | Achilli et al. (2007) | 6.40% |

| Europe | Portugal (South) | 203 | Achilli et al. (2007) | 10.84% |

| Europe | Portugal | 549 | Pereira et al. (2005) | 5.83% |

| Europe | Portugal (North) | 187 | Pereira et al. (2005) | 3.21% |

| Europe | Portugal (Central) | 239 | Pereira et al. (2005) | 5.02% |

| Europe | Portugal (South) | 123 | Pereira et al. (2005) | 11.38% |

| Europe | Portugal (Madeira) | 155 | Brehm et al. (2003) | 12.90% |

| Europe | Portugal (Açores) | 179 | Brehm et al. (2003) | 3.40% |

| Europe | Portugal (Alcacer do Sal) | 50 | Pereira et al. (2010) | 22.00% |

| Europe | Portugal (Coruche) | 160 | Pereira et al. (2010) | 8.70% |

| Europe | Portugal (Pias) | 75 | Pereira et al. (2010) | 3.90% |

| Europe | Portugal | 1429 | Barral-Arca et al. (2016) | 6.16% |

| West Asia | Yemen | 115 | Kivisild et al. (2004) | 45.70% |

| West Aasia | Yemen (Jews) | 119 | Behar et al. (2008) | 16.81% |

| West Asia | Bedouins (Israel) | 58 | Behar et al. (2008) | 15.50% |

| West Asia | Palestinians (Israel) | 117 | Achilli et al. (2007) | 13.68% |

| West Asia | Jordania | 494 | Achilli et al. (2007) | 12.50% |

| West Asia | Iraq | 116 | Achilli et al. (2007) | 9.48% |

| West Asia | Syria | 328 | Achilli et al. (2007) | 9.15% |

| West Asia | Saudi Arabia | 120 | Abu-Amero et al. (2007) | 6.66% |

| West Asia | Lebanon | 176 | Achilli et al. (2007) | 2.84% |

| West Asia | Druzes (Israel) | 77 | Behar et al. (2008) | 2.60% |

| West Asia | Kurds | 82 | Achilli et al. (2007) | 2.44% |

| West Asia | Turkey | 340 | Achilli et al. (2007) | 1.76% |

| South America | Colombia (Antioquia) | 113 | Bedoya et al. (2006) | 8.00% |

| North America | Mexico (North-Central) | 223 | Green et al. (2000) | 4.50% |

| South America | Argentina | 246 | Corach et al. (2009) | 2.03% |

See also

References

- 1 2 Soares P, Ermini L, Thomson N, et al. (June 2009). "Correcting for purifying selection: an improved human mitochondrial molecular clock". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 84 (6): 740–59. PMC 2694979

. PMID 19500773. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.05.001.

. PMID 19500773. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.05.001. - 1 2 Gonder MK, Mortensen HM, Reed FA, de Sousa A, Tishkoff SA (March 2007). "Whole-mtDNA genome sequence analysis of ancient African lineages". Mol. Biol. Evol. 24 (3): 757–68. PMID 17194802. doi:10.1093/molbev/msl209.

- ↑ Olivieri A, Achilli A, Pala M, et al. (December 2006). "The mtDNA legacy of the Levantine early Upper Palaeolithic in Africa". Science. 314 (5806): 1767–70. PMID 17170302. doi:10.1126/science.1135566.

- ↑ Cherni L, Fernandes V, Pereira JB, et al. (June 2009). "Post-last glacial maximum expansion from Iberia to North Africa revealed by fine characterization of mtDNA H haplogroup in Tunisia". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 139 (2): 253–60. PMID 19090581. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20979.

- ↑ Behar DM, Villems R, Soodyall H, et al. (May 2008). "The dawn of human matrilineal diversity". American Journal of Human Genetics. 82 (5): 1130–40. PMC 2427203

. PMID 18439549. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.04.002.

. PMID 18439549. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.04.002. - ↑ Gonder MK, Mortensen HM, Reed FA, de Sousa A, Tishkoff SA (March 2007). "Whole-mtDNA genome sequence analysis of ancient African lineages". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 24 (3): 757–68. PMID 17194802. doi:10.1093/molbev/msl209.

the presence of haplogroups N1 and J in Tanzania suggest "back" migration from the Middle East or Eurasia into eastern Africa, which has been inferred from previous studies of other populations in eastern Africa

- 1 2 Rosa A. et al. 2004, MtDNA Profile of West Africa Guineans: Towards a Better Understanding of the Senegambia Region.

- 1 2 3 4 Abu-Amero KK, Larruga JM, Cabrera VM, González AM (2008). "Mitochondrial DNA structure in the Arabian Peninsula". BMC Evol. Biol. 8: 45. PMC 2268671

. PMID 18269758. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-8-45.

. PMID 18269758. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-8-45. - ↑ Kivisild T, Reidla M, Metspalu E, et al. (November 2004). "Ethiopian mitochondrial DNA heritage: tracking gene flow across and around the gate of tears". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 75 (5): 752–70. PMC 1182106

. PMID 15457403. doi:10.1086/425161.

. PMID 15457403. doi:10.1086/425161. - 1 2 3 4 5 Tishkoff SA, Gonder MK, Henn BM, et al. (October 2007). "History of click-speaking populations of Africa inferred from mtDNA and Y chromosome genetic variation". Mol. Biol. Evol. 24 (10): 2180–95. PMID 17656633. doi:10.1093/molbev/msm155.

- ↑ Anderson, Sadie 2006, Phylogenetic and phylogeographic analysis of African mitochondrial DNA variation. Archived 2011-09-10 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Salas A, Richards M, De la Fe T, et al. (November 2002). "The making of the African mtDNA landscape". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 71 (5): 1082–111. PMC 385086

. PMID 12395296. doi:10.1086/344348.

. PMID 12395296. doi:10.1086/344348. - ↑ Chen YS, Olckers A, Schurr TG, Kogelnik AM, Huoponen K, Wallace DC (April 2000). "mtDNA variation in the South African Kung and Khwe-and their genetic relationships to other African populations". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 66 (4): 1362–83. PMC 1288201

. PMID 10739760. doi:10.1086/302848.

. PMID 10739760. doi:10.1086/302848. - ↑ Quintana, Lluis et al 2003, MtDNA diversity in Central Africa: from hunter-gathering to agriculturalism

- ↑ Cherni L, Loueslati BY, Pereira L, Ennafaâ H, Amorim A, El Gaaied AB (February 2005). "Female gene pools of Berber and Arab neighboring communities in central Tunisia: microstructure of mtDNA variation in North Africa". Human Biology. 77 (1): 61–70. PMID 16114817. doi:10.1353/hub.2005.0028.

- ↑ Turchi C, Buscemi L, Giacchino E, et al. (June 2009). "Polymorphisms of mtDNA control region in Tunisian and Moroccan populations: an enrichment of forensic mtDNA databases with Northern Africa data". Forensic Science International: Genetics. 3 (3): 166–72. PMID 19414164. doi:10.1016/j.fsigen.2009.01.014.

- ↑ Behar DM, Metspalu E, Kivisild T, et al. (2008). MacAulay V, ed. "Counting the founders: the matrilineal genetic ancestry of the Jewish Diaspora". PLoS ONE. 3 (4): e2062. PMC 2323359

. PMID 18446216. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002062.

. PMID 18446216. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002062. - ↑ Harich et al 2010 (May 10, 2010). "The trans-Saharan slave trade - clues from interpolation analyses and high-resolution characterization of mitochondrial DNA lineages". BMC Evolutionary Biology. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ↑ Cerný V, Mulligan CJ, Rídl J, et al. (June 2008). "Regional differences in the distribution of the sub-Saharan, West Eurasian, and South Asian mtDNA lineages in Yemen". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 136 (2): 128–37. PMID 18257024. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20784.

- ↑ Whale, John Willian (September 2012). "Mitochondrial DNA Analysis of Four Ethnic Groups of Afghanistan" (PDF). University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- 1 2 Achilli A, Olivieri A, Pala M, et al. (April 2007). "Mitochondrial DNA variation of modern Tuscans supports the near eastern origin of Etruscans". American Journal of Human Genetics. 80 (4): 759–68. PMC 1852723

. PMID 17357081. doi:10.1086/512822.

. PMID 17357081. doi:10.1086/512822. - ↑ Abu-Amero KK, González AM, Larruga JM, Bosley TM, Cabrera VM (2007). "Eurasian and African mitochondrial DNA influences in the Saudi Arabian population". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 7: 32. PMC 1810519

. PMID 17331239. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-32.

. PMID 17331239. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-32. - ↑ Pereira L, Cunha C, Alves C, Amorim A (April 2005). "African female heritage in Iberia: a reassessment of mtDNA lineage distribution in present times". Human Biology. 77 (2): 213–29. PMID 16201138. doi:10.1353/hub.2005.0041.

- ↑ Casas MJ, Hagelberg E, Fregel R, Larruga JM, González AM (December 2006). "Human mitochondrial DNA diversity in an archaeological site in al-Andalus: genetic impact of migrations from North Africa in medieval Spain". Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 131 (4): 539–51. PMID 16685727. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20463.

- ↑ Brehm A, Pereira L, Kivisild T, Amorim A (December 2003). "Mitochondrial portraits of the Madeira and Açores archipelagos witness different genetic pools of its settlers". Human Genetics. 114 (1): 77–86. PMID 14513360. doi:10.1007/s00439-003-1024-3.

- ↑ Alvarez L, Santos C, Ramos A, Pratdesaba R, Francalacci P, Aluja MP (August 2010). "Mitochondrial DNA patterns in the Iberian Northern plateau: population dynamics and substructure of the Zamora province". Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 142 (4): 531–9. PMID 20127843. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21252.

- ↑ Alvarez L, Santos C, Ramos A, Pratdesaba R, Francalacci P, Aluja MP (August 2010). "Mitochondrial DNA patterns in the Iberian Northern plateau: population dynamics and substructure of the Zamora province". Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 142 (4): 531–9. PMID 20127843. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21252.

As regards sub-Saharan Hgs (L1b, L2b, and L3b), the high frequency found in the southern regions of Zamora, 18.2% in Sayago and 8.1% in Bajo Duero, is comparable to that described for the South of Portugal

- ↑ Ottoni C, Martinez-Labarga C, Vitelli L, et al. (2009). "Human mitochondrial DNA variation in Southern Italy". Annals of Human Biology. 36 (6): 785–811. PMID 19852679. doi:10.3109/03014460903198509.

- ↑ Pena, S.D.J.; Bastos-Rodrigues, L.; Pimenta, J.R.; Bydlowski, S.P. (2009). "DNA tests probe the genomic ancestry of Brazilians". Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 42 (10): 870–876. PMID 19738982. doi:10.1590/S0100-879X2009005000026.

- ↑ Alves-Silva J, da Silva Santos M, Guimarães PE, et al. (August 2000). "The ancestry of Brazilian mtDNA lineages". American Journal of Human Genetics. 67 (2): 444–61. PMC 1287189

. PMID 10873790. doi:10.1086/303004.

. PMID 10873790. doi:10.1086/303004. - ↑ Bobillo MC, Zimmermann B, Sala A, et al. (August 2009). "Amerindian mitochondrial DNA haplogroups predominate in the population of Argentina: towards a first nationwide forensic mitochondrial DNA sequence database". International Journal of Legal Medicine. 124 (4): 263–8. PMID 19680675. doi:10.1007/s00414-009-0366-3.

- ↑ Bedoya G, Montoya P, García J, et al. (May 2006). "Admixture dynamics in Hispanics: a shift in the nuclear genetic ancestry of a South American population isolate". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (19): 7234–9. PMC 1464326

. PMID 16648268. doi:10.1073/pnas.0508716103.

. PMID 16648268. doi:10.1073/pnas.0508716103. - ↑ Green LD, Derr JN, Knight A (March 2000). "mtDNA affinities of the peoples of North-Central Mexico". American Journal of Human Genetics. 66 (3): 989–98. PMC 1288179

. PMID 10712213. doi:10.1086/302801.

. PMID 10712213. doi:10.1086/302801. - ↑ Gonçalves VF, Prosdocimi F, Santos LS, Ortega JM, Pena SD (2007). "Sex-biased gene flow in African Americans but not in American Caucasians". Genetics and Molecular Research. 6 (2): 256–61. PMID 17573655.

- ↑ Josef Caruana et al. 2016, The Genetic Heritage of the Maltese Islands: A Matrilineal perspective

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Macro-haplogroup L (mtDNA). |

- PhyloTree.org - mtDNA subtree L, Macro-haplogroup L by van Oven & Kayser M.

|

Phylogenetic tree of human mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroups | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mitochondrial Eve (L) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| L0 | L1–6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| L1 | L2 | L3 | L4 | L5 | L6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| M | N | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CZ | D | E | G | Q | O | A | S | R | I | W | X | Y | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C | Z | B | F | R0 | pre-JT | P | U | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| HV | JT | K | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| H | V | J | T | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||