Yōkai

| Part of the series on |

| Japanese mythology and folklore |

|---|

|

| Mythic texts and folktales |

| Divinities |

| Legendary creatures and spirits |

| Legendary figures |

| Mythical and sacred locations |

| Sacred objects |

| Shintō and Buddhism |

| Folklorists |

Yōkai (妖怪, ghost, phantom, strange apparition) are a class of supernatural monsters, spirits and demons in Japanese folklore. The word yōkai is made up of the kanji for "bewitching; attractive; calamity;" and "spectre; apparition; mystery; suspicious".[1] They can also be called ayakashi (あやかし), mononoke (物の怪), or mamono (魔物). Yōkai range diversely from the malevolent to the mischievous, or occasionally bring good fortune to those who encounter them. Often they possess animal features (such as the Kappa, which is similar to a turtle, or the Tengu which has wings), other times they can appear mostly human, some look like inanimate objects and others have no discernible shape. Yōkai usually have spiritual or supernatural power, with shapeshifting being one of the most common. Yōkai that have the ability to shapeshift are called bakemono (化物) / obake (お化け).

Japanese folklorists and historians use yōkai as "supernatural or unaccountable phenomena to their informants". In the Edo period, many artists, such as Toriyama Sekien, created yōkai inspired by folklore or their own ideas, and in the present, several yōkai created by them (e.g. Kameosa and Amikiri, see below) are wrongly considered as being of legendary origin.[2]

Concept

What is thought of as supernatural depends on the time period, but generally it is considered that the older the time period, the more phenomena were considered supernatural.[4]

According to the ancient ideas of animism, a spirit-like being called a "mononoke" among other things was thought to reside in all things.[5] It was believed that these spirits possessed various kinds of emotions, and if the spirit was peaceful, it was a nigi-mitama that brought about good fortune such as a good harvest, and if the spirit was violent, it was an ara-mitama that brought about ill fortune such as natural disasters and illness, and the ritual for converting ara-mitama into nigi-mitama was called the chinkon ("the calming of the spirits").[6] One's ancestors, other well-respected people, and sometimes even nature and animals depending on the area were considered nigi-mitama that became protective gods that received worship. At the same time, people also tried performing chinkon rituals in order to quell the misfortune-making beings from making any more misfortune and fear, the misfortunes and fears that were still unexplained in those eras.[7] In other words, yokai-like beings can be said to be from the ara-mitama that weren't deified, failed to be deified, or stopped being deified.[8]

As time went on, the things that were thought of as supernatural became fewer and fewer. At the same time, yokai became depicted in emaki and paintings that stabilized how they appeared, turned them into characters, lessened their fearful nature, and became subjects of entertainment as time went on. The tendency to use yokai as objects of entertainment can be seen starting from the middle ages,[9] and becoming definitive in the Edo periods and beyond.[10]

Types

The folkloricist Tsutomu Ema looked at various literature on legends, folklore, and paintings and divided yokai and henge (変化, or "mutants") into various categories, which was presented in the Nihon Yokai Henge Shi and the Obake no Rekishi.

- 5 categories that depended on what its "true form" is: a human, animal, plant, object, or natural phenomenon.

- 4 categories that depended on how they mutated: this-world related, spiritual/mental related, reincarnation (next-world) related, or material related.

- 7 categories that depended on how they appeared: human, animal, plant, object, structure/building, thing from nature, and miscellaneous, as well as compound categories that fall into more than one category.

In Japanese folkloristics, yokai are divided into categories depending on where they reportedly appear, and they are indexed as follows in the book Sogo Nihon Minzoku Goi (綜合日本民俗語彙, "A Complete Dictionary of Japanese Folklore"):[11]

- Yama no ke (mountains), michi no ke (paths), ki no ke (trees), mizu no ke (water), umi no ke (the sea), yuki no ke (snow), oto no ke (sound), doubutsu no ke (animals, either real or imagined)

History

Ancient history

- First century: there is a book from what is now China titled 循史伝 with the statement "the spectre (yokai) was in the imperial court for a long time. The king asked Tui for the reason. He answered that there was great anxiety and he gave a recommendation to empty the imperial room" (久之 宮中数有妖恠(妖怪) 王以問遂 遂以為有大憂 宮室将空), thus using "妖恠" to mean "phenomenon that surpasses human knowledge."

- Houki 8 (772): in the Shoku Nihongi, there is the statement "shinto purification is performed because yokai appear very often in the imperial court, (大祓、宮中にしきりに、妖怪あるためなり)," using the word "yokai" to mean not anything in particular, but strange phenomena in general.

- Middle of the Heian era (794-1185/1192): In The Pillow Book by Sei Shōnagon, there is the statement "there are tenacious mononoke (いと執念き御もののけに侍るめり)" as well as a statement by Murasaki Shikibu that "the mononoke have become quite dreadful (御もののけのいみじうこはきなりけり)," which are the first appearances of the word "mononoke."

- Koubu 3 (1370): In the Taiheiki, in the fifth volume, there is the statement, "Sagami no Nyudo was not at all frightened by yokai."

The ancient times were a period abundant in literature and folktales mentioning and explaining yokai. Literature such as the Kojiki, the Nihon Shoki, and various Fudoki expositioned on legends from the ancient past, and mentions of oni, orochi, among other kinds of mysterious phenomena can already be seen in them.[12] In the Heian period, collections of stories about youkai and other supernatural phenomena were published in multiple volumes, starting with publications such as the Nihon Ryōiki and the Konjaku Monogatarishū, and in these publications, mentions of phenomena such as Hyakki Yagyō can be seen.[13] The yokai that appear in these literature were passed on to later generations.[14] However, despite the literature mentioning and explaining these yokai, they were never given any visual depictions. In Buddhist paintings such as the Hell Scroll (Nara National Museum), which came from the later Heian period, there are visual expressions of the idea of oni, but actual visual depictions would only come later in the middle ages, from the Kamakura period and beyond.[15]

Yamata no Orochi was originally a local god but turned into a youkai that was slain by Susanoo.[16] Yasaburo was originally a bandit whose vengeful spirit (onryo) turned into a poisonous snake upon death and plagued the water in a paddy, but eventually became deified as the "wisdom god of the well (井の明神)."[17] Kappa and inugami are sometimes treated as gods in one area and youkai in other areas. From these examples, it can be seen that among Japanese gods, there are some beings that can go from god to youkai and vice versa.[18]

Post-classical history

Medieval Japan was a time period where publications such as Emakimono, Otogizōshi, and other visual depictions of yokai started to appear. While there were religious publications such as the Jisha Engi (寺社縁起), others, such as the Otogizōshi, were intended more for entertainment, starting the trend where yokai became more and more seen as subjects of entertainment. For examples, tales of yokai extermination could be said to be a result of emphasizing the superior status of human society over yokai.[9] Publications included:

- The Ooe-yama Shuten-doji Emaki (about an oni), the Zegaibou Emaki (about a tengu), the Tawara no Touta Emaki (俵藤太絵巻) (about a giant snake and a centipede), the Tsuchigumo Zoshi (土蜘蛛草紙) (about tsuchigumo), and the Dojo-ji Engi Emaki (about a giant snake). These emaki were about yokai that come from even older times.

- The Kitano Tenjin Engi Emaki, in which Sugawara no Michizane was a lightning god who took on the form of an oni, and despite attacking people after doing this, he was still deified as a god in the end.[9]

- The Junirui Emaki, the Tamamono Soshi, (both about Tamamo-no-Mae), and the Fujibukuro Soushi Emaki (about a monkey). These emaki told of yokai mutations of animals.

- The Tsukumogami Emaki, which told tales of thrown away none-too-precious objects that come to have a spirit residing in them planning evil deeds against humans, and ultimately get exorcised and sent to peace.

- The Hyakki Yagyō Emaki, depicting many different kinds of yokai all marching together

In this way, yokai that were mentioned only in writing were given a visual appearance in the middle ages. In the Otogizōshi, familiar tales such as Urashima Tarō and Issun-bōshi also appeared.

The next major change in yokai came after the period of warring states, in the Edo period.

Modern history

Edo period

- Enpō 6 (1677): Publication of the Shokoku Hyakumonogatari, a collection of tales of various monsters.

- Hōei 6 (1706): Publication of the Otogi Hyakumonogatari. In volumes such as "Miyazu no Ayakashi" (volume 1) and "Unpin no Yokai" (volume 4), collections of tales that seem to come from China were adapted into a Japanese setting.[19]

- Shōtoku 2 (1712): Publication of the Wakan Sansai Zue by Terajima Ryōan, a collection of tales based on the Chinese Sancai Tuhui.

- Shōtoku 6 (1716): In the specialized dictionary Sesetsu Kojien (世説故事苑), there is an entry on yokai, which stated, "among the commoners in my society, there are many kinds of kaiji (mysterious phenomena), often mispronounced by commoners as 'kechi.' Types include the cry of weasels, the howling of foxes, the bustling of mice, the rising of the chicken, the cry of the birds, the pooping of the birds on clothing, and sounds similar to voices that come from cauldrons and bottles. These types of things appear in the Shōseiroku, methods of exorcising them can be seen, so it should serve as a basis"[20]

- Tenmei 8 (1788): Publication of the Bakemono chakutocho by Masayoshi Kitao. This was a kibyoshi diagram book of yokai, but it was prefaced with the statement "it can be said that the so-called yokai in our society is a representation of our feelings that arise from fear" (世にいふようくわいはおくびょうよりおこるわが心をむかふへあらわしてみるといえども…),[21] and already in this era, while yokai were being researched, it indicated that there were people who questioned whether yokai really existed or not.

It was in this era that the technology of the printing press and publication was first started to be widely used, that a publishing culture developed, and was frequently a subject of kibyoshi[22] and other publications.

As a result, kashi-hon shops that handled such books spread and became widely used, making the general public's impression of each yokai fixed, spreading throughout all of Japan. For example, before the Edo period, there were plenty of interpretations about what the yokai that were classified as "kappa," but because of books and publishing, the notion of "kappa" became anchored to what is now the modern notion of kappa. Also, including other kinds of publications, other than yokai born from folk legend, there were also many invented yokai that were created through puns or word plays, and the Gazu Hyakki Hagyo by Sekien Toriyama is one example of that. Also, when the Hyakumonogatari Kaidankai became popular in the Edo period, it is thought that one reason for the appearance of new yokai was a demand for entertaining ghost stories about yokai no one has ever heard of before, resulting in some yokai that were simply made up for the purpose of telling an entertaining story, and the kasa-obake and the tōfu-kozō are known examples of these.[23]

They are also frequently depicted in ukiyo-e, and there are artists that have drawn famous yokai like Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Yoshitoshi, Kawanabe Kyōsai, and Hokusai, and there are also Hyakki Yagyō books made by artists of the Kanō school.

In this period, toys and games like karuta, sugoroku, pogs frequently used yokai as characters. Thus, with the development of a publishing culture, yokai depictions that were treasured in temples and shrines were able to become something more familiar to people, and it is thought that this is the reason that even though yokai were originally things to be feared, they have then became characters that people feel close to.[24]

Meiji period

- Meiji 24 (1891): Publication of the Seiyou Youkai Kidan by Shibue Tamotsu. It introduced folktales from Europe, such as the Grimm Tales.

- Meiji 29 (1896): Publication of the Yokaigaku Kogi by Inoue Enryō

- Meiji 33 (1900): Performance of the kabuki Yami no Ume Hyakumonogatari at the Kabuki-za in January. It was a performance in which appeared numerous yokai such as the kasa ippon ashi, skeletons, yuki-onna, okasabe-hime, among others. Onoe Kikugorō V played the role of many of these, such as the okasabe-hime.

- Taishō 3 (1914): Publication of the Shokubutsu Kaiko by Mitsutaro Shirai. Shirai expositioned on plant yokai from the point of view of a plant pathologist and herbalist.

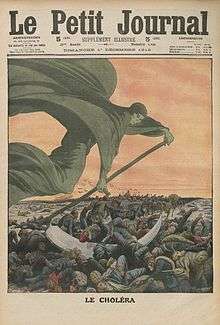

With the Meiji Restoration, Western ideas and translated western publications began to make an impact, and western tales were particularly sought after. Things like binbogami, yakubyogami, and shinigami were talked about, and shinigami were even depicted in classical rakugo, and although the shinigami were misunderstood as a kind of Japanese yokai or kami, they actually became well-known among the populace through a rakugo called "Shinigami" in San'yūtei Enchō, which were adoptions of European tales such as the Grimm fairy tale "Godfather Death" and the Italian opera "Crispino" (1850). Also, in Meiji 41 (1908), Kyōka Izumi and Tobari Chikufuu jointedly translated Gerhart Hauptmann's play The Sunken Bell. Later works of Kyōka such as Yasha ga Ike were influenced by The Sunken Bell, and so it can be seen that folktales that come from the West became adapted into Japanese tales of yokai.

Shōwa period

Since yokai are introduced in various kinds of media, they have become well-known among the old, young, men and women. The kamishibai from before the war, and the manga industry, as well as the kashi-hon shops that continued to exist until around Showa 40 (the 1970s), as well as television contributed to the public knowledge and familiarity with yokai. Yokai plays a role in attracting tourism revitalizing local regions, like the places depicted in the Tono Monogatari like Tono, Iwate, Iwate Prefecture and the Tottori Prefecture, which is Shigeru Mizuki's place of birth. In Kyoto, there is a store called Yokaido, which is a renovated machiya (traditional Kyoto-style house), and the owner gives a guided yokai tour of Kyoto.

In this way, Yokai are told about in legends in various forms, but traditional oral story telling by the elders and the older people is rare, and regionally unique situations and background in oral story telling are not easily conveyed. For example, the classical yokai represented by tsukumogami can only be felt as something realistic by living close to nature, such as with tanuki (Japanese racoon dogs), foxes and weasels. Furthermore, in the suburbs, and other regions, even when living in a primary-sector environment, there are tools that are no longer seen, such as the inkstone, the kama (a large cooking pot), or the tsurube (a bucket used for getting water from a well), and there exist yokai that are reminiscent of old lifestyles such as the azukiarai and the dorotabo. As a result, even for those born in the first decade of the Showa period (1925-1935), except for some who were evacuated to the countryside, they would feel that those things that become yokai are "not familiar" are "not very understandable." For example, in classical rakugo, even though people understand the words and what they refer to, they are not able to imagine it as something that could be realistic. Thus, the modernization of society has had a negative effect on the place of yokai in classical Japanese culture.

On the other hand, the yokai introduced through mass media are not limited to only those that come from classical sources like folklore, and just like in the Edo period, new fictional yokai continue to be invented, such as scary school stories and other urban legends like kuchisake-onna and Hanako-san, giving birth to new yokai. From 1975 onwards, starting with the popularity of kuchisake-onna, these urban legends began to be referred to in mass media as "modern yokai."[25] This terminology was also used in recent publications dealing with urban legends,[26] and the researcher on yokai, Bintarō Yamaguchi, used this especially frequently.[25]

During the 1970s, many books were published that introduced yokai through encyclopaedias, illustrated reference books, and dictionaries as a part of children's horror books, but along with the yokai that come from classics like folklore, kaidan, and essays, it has been pointed out by modern research that there are some mixed in that do not come from classics, but were newly created. Some well-known examples of these are the gashadokuro and the jubokko. For example, Arifumi Sato is known to be a creator of modern yokai, and Shigeru Mizuki, a manga artist for yokai, in writings concerning research about yokai, pointed out that newly created yokai do exist,[27][28] and Mizuki himself, through GeGeGe no Kitaro, created about 30 new yokai.[29] There has been much criticism that this mixing of classical yokai with newly created yokai is making light of tradition and legends.[27][28] However, since there have already been those from the Edo period like Sekien Toriyama who created many new yokai, there is also the opinion that it is unreasonable to criticize modern creations without doing the same for classical creations too.[27] Furthermore, there is a favorable view that says that introducing various yokai characters through these books nurtured creativity and emotional development of young readers of the time.[28]

In media

Various kinds of yōkai are encountered in folklore and folklore-inspired art and literature.

Famous works and authors

- The Gazu Hyakki Yagyō by ukiyo-e artist Toriyama Sekien (1712-1788)

- The Ugetsu Monogatari by author Ueda Akinari (1734-1809)

- Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things, a collection of Japanese ghost stories by Lafcadio Hearn (1850-1904) includes stories of yūrei and yōkai such as Yuki-onna, and is one of the first Western publications of its kind.

- The Castle Tower by author Kyōka Izumi (1873-1939)

- GeGeGe no Kitaro and Kappa no Sanpei among other works by manga artist Shigeru Mizuki (1922-2015), keep yōkai in the popular imagination.

- Shabake by author Megumi Hatakenaka (1959-)

- The Wicked and the Damned: A Hundred Tales of Karma by Natsuhiko Kyogoku (1963-)

Other popular works focusing on yōkai include the Nurarihyon no Mago series, Yu Yu Hakusho, Inuyasha: A Feudal Fairy Tale, Yo-kai Watch and the 1960s Yokai Monsters film series, which was loosely remade in 2005 as Takashi Miike's The Great Yokai War. They often play major roles in Japanese fiction.

See also

- Dokkaebi

- Genius

- Jinn

- Kijimunaa (legendary beings from Ryukyu Islands)

- List of legendary creatures from Japan

- Obake

- Oni

- Tengu

- Tsukumogami

- Yaoguai

- Yōsei

- Yūrei

References

- ↑ Youkai Kanji and Youkai Definition via Denshi Jisho at jisho.org Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ↑ "Toriyama Sekien ~ 鳥山石燕 (とりやませきえん) ~ part of The Obakemono Project: An Online Encyclopedia of Yōkai and Bakemono". Obakemono.com. Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 2013-04-30.

- ↑ 近藤瑞木・佐伯 孝弘 2007

- ↑ 小松和彦 2015, p. 24

- ↑ 小松和彦 2011, p. 16

- ↑ 小松和彦 2011, pp. 16–18

- ↑ 宮田登 2002, p. 14、小松和彦 2015, pp. 201–204

- ↑ 宮田登 2002, pp. 12–14、小松和彦 2015, pp. 205–207

- 1 2 3 小松和彦 2011, pp. 21–22

- ↑ 小松和彦 2011, pp. 188–189

- ↑ 民俗学研究所『綜合日本民俗語彙』第5巻 平凡社 1956年 403-407頁 索引では「霊怪」という部門の中に「霊怪」「妖怪」「憑物」が小部門として存在している。

- ↑ 小松和彦 2011, p. 20

- ↑ 『今昔物語集』巻14の42「尊勝陀羅尼の験力によりて鬼の難を遁るる事」

- ↑ 小松和彦 2011, p. 78

- ↑ 小松和彦 2011, p. 21

- ↑ 小松和彦 2015, p. 46

- ↑ 小松和彦 2015, p. 213

- ↑ 宮田登 2002, p. 12、小松和彦 2015, p. 200

- ↑ 太刀川清 (1987). 百物語怪談集成. 国書刊行会. pp. 365–367.

- ↑ "世説故事苑 3巻". Retrieved 2015-12-16.

- ↑ 江戸化物草紙. アダム・カバット校注・編. 小学館. February 1999. p. 29. ISBN 978-4-09-362111-3.

- ↑ 草双紙 といわれる 絵本 で、ジャンルごとにより表紙が色分けされていた。黄表紙は大人向けのもので、その他に赤や青がある。

- ↑ 多田克己 (2008). "『妖怪画本・狂歌百物語』妖怪総覧". In 京極夏彦 ・多田克己編. 妖怪画本 狂歌百物語. 国書刊行会. pp. 272–273頁. ISBN 978-4-3360-5055-7.

- ↑ 湯本豪一 (2008). "遊びのなかの妖怪". In 講談社コミッククリエイト編. DISCOVER妖怪 日本妖怪大百科. KODANSHA Official File Magazine. VOL.10. 講談社. pp. 30–31頁. ISBN 978-4-06-370040-4.

- 1 2 山口敏太郎 (2007). 本当にいる日本の「現代妖怪」図鑑. 笠倉出版社. pp. 9頁. ISBN 978-4-7730-0365-9.

- ↑ "都市伝説と妖怪". DISCOVER妖怪 日本妖怪大百科. VOL.10. pp. 2頁.

- 1 2 3 と学会 (2007). トンデモ本の世界U. 楽工社. pp. 226–231. ISBN 978-4-903063-14-0.

- 1 2 3 妖怪王(山口敏太郎)グループ (2003). 昭和の子供 懐しの妖怪図鑑. コスモブックス. アートブック本の森. pp. 16–19. ISBN 978-4-7747-0635-1.

- ↑ 水木しげる (1974). 妖怪なんでも入門. 小学館入門百科シリーズ. 小学館. p. 17. ISBN 978-4-092-20032-6.

Further reading

- Ballaster, R. (2005). Fables Of The East, Oxford University Press.

- Hearn, L. (2005). Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things, Tuttle Publishing.

- Phillip, N. (2000). Annotated Myths & Legends, Covent Garden Books.

- Tyler, R. (2002). Japanese Tales (Pantheon Fairy Tale & Folklore Library), Random House, ISBN 978-0-3757-1451-1.

- Yoda, H. and Alt, M. (2012). Yokai Attack!, Tuttle Publishing, ISBN 978-4-8053-1219-3.

- Meyer, M. (2012). The Night Parade of One Hundred Demons, ISBN 978-0-9852-1840-9.

- (in German) Fujimoto, Nicole. "Yôkai und das Spiel mit Fiktion in der edozeitlichen Bildheftliteratur" (Archive" (Archive). Nachrichten der Gesellschaft für Natur- und Völkerkunde Ostasiens (NOAG), University of Hamburg. Volume 78, Issues 183–184 (2008). p. 93-104.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yōkai. |

- Youkai and Kaidan (PDF; 1.1 MB)

- Tales of Ghostly Japan

- Hyakumonogatari.com Translated yokai stories from Hyakumonogatari.com

- The Ooishi Hyoroku Monogatari Picture Scroll

- Database of images of Strange Phenomena and Yokai (Monstrous Beings)

- Yokai.com an illustrated database of yōkai and ghosts