Handsworth, West Midlands

| Handsworth | |

|---|---|

Soho Road | |

Handsworth | |

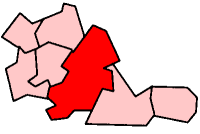

| Handsworth shown within the West Midlands | |

| OS grid reference | SP 040 896 |

| Metropolitan borough | |

| Metropolitan county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BIRMINGHAM |

| Postcode district | B20/B21 |

| Police | West Midlands |

| Fire | West Midlands |

| Ambulance | West Midlands |

| EU Parliament | West Midlands |

Handsworth (grid reference SP035905) is now an inner city, urban area of northwest Birmingham in the West Midlands. Handsworth lies just outside the Birmingham City Centre.

History

The name Handsworth originates from its Saxon owner Hondes and the Old English word weorthing, meaning farm or estate. It was recorded in the Domesday Survey of 1086, as a holding of William Fitz-Ansculf, the Lord of Dudley, although at that time it would only have been a very small village surrounded by farmland and extensive woodland.

Historically in the county of Staffordshire,[1] it remained a small village from the 13th century to the 18th century. Accommodation was built for factory workers, the village quickly grew, and in 1851, there were more than 6,000 people living in the township. In that year, work began to build St James' Church. Later St Michael's Church was built as a daughter church to St James'. In the census of 1881, the town was recorded as having approx. 32,000 residents. By the census of 1911, this had more than doubled to 68,610.

The development of the built environment was sporadic and many of Handsworth's streets display a mixture of architectural types and periods – among them some of the finest Victorian buildings in the city. Handsworth has two grammar schools – Handsworth Grammar School and King Edward VI Handsworth School (for girls). St Andrew's Church is a listed building in Oxhill Road which also held Sunday school classes in a small building on the corner of Oxhill Road and Church Lane. It also contains Handsworth Park, which in 2006 underwent a major restoration, the vibrant shopping area of Soho Road and St. Mary's Church containing the remains of the founders of the Industrial Revolution - Watt, Murdoch and Boulton. The 1901 Red Lion public house was grade II* listed in 1985, but has been empty since 2008 and is considered "at risk".[2]

Handsworth parish was transferred from Staffordshire to Warwickshire, and became part of Birmingham, in 1911.[1] The redbrick building with the clocktower in the photograph was originally the offices of the district council on Soho Road.

Birmingham historian Dr. Carl Chinn noted that during World War II the boundary between Handsworth and the outlying suburb of Handsworth Wood marked the line between being safe and unsafe from bombing, with Handsworth Wood being an official evacuation zone, despite being at least ten miles away from any countryside that might now qualify as "green belt" land, and being on the periphery of many "high risk" areas.[3] During World War II, West Indians had arrived as part of the colonial war effort, where they worked in Birmingham munitions factories. In the post-war period, a rebuilding programme required much unskilled labour and Birmingham's industrial base expanded, significantly increasing the demand for both skilled and unskilled workers. During this time, there was direct recruitment for workers from the Caribbean and the area became a centre for Birmingham's Afro-Caribbean community.

A tram depot was erected near Birmingham Road, next to the border with West Bromwich, during the 1880s, and remained in use until the tram service ended in 1939. Although it has since been demolished, a replica of the depot was created later in the 20th century at the Black Country Living Museum in Dudley.[4]

The West Indian population in Birmingham numbered over 17,000 by the 1961 census count. In addition, during this time, Indians, particularly Sikhs from the Punjab arrived in Birmingham, many of them working in the foundries and on the production lines in motor vehicle manufacturing, mostly at the Longbridge plant some 10 miles away.

By the early 1960s, there was much racial tension in the country and a great deal of this was being felt in Handsworth.

Boulton and Watt

Matthew Boulton's Soho Manufactory was set up on the northern edge of Handsworth, on Handsworth Heath. It operated from 1766-1848 and was demolished in 1863. Boulton commissioned Samuel Wyatt to design his nearby house Soho House, which is now a museum.

In 1790, Heathfield Hall, also designed by Wyatt, was built for Boulton's business partner, the engineer James Watt. Watt died in the house in 1819, and was buried at nearby St Mary's Church. In the 1880s engineer George Tangye bought the hall and lived there until his death in 1920. From 1927 the hall was demolished and the lands redeveloped.[5][6] What was the Heathfield Estate is now the land that comprises West Drive and North Drive. Watt's workshop from the house was dismantled and rebuilt in the Science Museum, London.

Civil unrest and social issues

A riot occurred in 1981, during which similar riots took place in London, Leeds and Liverpool. Handsworth's most notable rioting took place in September 1985 and also overspilled into neighbouring Lozells. As in many parts of Britain, the conflict between local black people and the police and other authorities was the start of unrest. The 1985 Handsworth riots claimed the life of a local post office manager, who was killed when a firebomb was hurled through the window of his shop. After the 1985 riots and a change in perception of British sub-urban integration, community relations were reviewed. Local government worked to improve community relations as a way of managing both racial and cultural differences. Encouragement was provided by arts organisations such as West Midlands Ethnic Minority Arts Service; its director, Pogus Caesar, documented the riots, and Black Audio Film Collective produced the 1986 film Handsworth Songs. Private groups such as Shades of Black work closely with the community.

Another riot occurred on 8 September 1991, and in 2005 further rioting broke out, in which one person was killed,[7] many injured, and damage to property occurred, resulting in the biggest investigation ever undertaken by West Midlands Police. The riots were sparked by rumours that a young black girl had been raped by a group of youths, although no evidence was found to suggest the crime took place, and the supposed victim was never found. On 8 August 2011, the UK riots spread to the Handsworth area, and hundreds of properties and shops were damaged.

In April 1994, The Independent reported that more than one third of the workforce in Handsworth was unemployed, and that prostitution and drugs were a widespread problem. There had also been at least one gang attack on fire crews in the area.[8]

Musical legacy

Handsworth has produced some notable popular musical acts: Steel Pulse (whose first studio album Handsworth Revolution is named after the area), Joan Armatrading, Pato Banton, Benjamin Zephaniah, Swami, Apache Indian, Ruby Turner and Bhangra group B21 and Jamaican musicians such as Mighty Diamonds, Alton Ellis, Burning Spear and Dennis Brown have performed in Handsworth, rare photographs of these musicians are held in Pogus Caesar's OOM Gallery Archive. In addition, hard rock band Black Sabbath's lead guitarist and song writer Tony Iommi, Steve Winwood, UK pop singer Jamelia and progressive rock drummer Carl Palmer were born in Handsworth.

The tenor Webster Booth was born in Handsworth in 1902, and began his singing career as a child chorister at the local parish church of St. Mary's. Together with his duettist wife Anne Ziegler, he became a mainstay of West End musicals and World War II musical films. A BBC Showbiz Hall of Fame article described him as "possessing one of the finest English tenor voices of the twentieth century."[9]

Events

Handsworth Park has hosted numerous events: The Birmingham Tattoo, The Birmingham Festival (both originally called Handsworth- rather than Birmingham) and the Flower Show, and in 1967 The Birmingham Dog Show. The Scouts Rally was another annual event held in the park for many years when Scouts from a wide area congregated and paraded. The Handsworth Carnival grew out of the Flower Show and Carnival; Caribbean-style carnivals began in Handsworth Park, in 1984, with a street procession via Holyhead Road. In 1994 the carnival was held in Handsworth Park for the last time. The following year it was moved from the park out onto the streets of Handsworth, since which time it has been known as the Birmingham International Carnival. In 1999, it was again held in a park, but this time in Perry Barr Park. Handsworth Park also hosts an annual Vaisakhi Mela.

Education

Among education providers is the Rookery School, a 100-year-old mixed state primary school, still housed largely in its original buildings.[10] [11] Secondary schools include Handsworth Wood Girls' Academy, Holyhead School, St John Wall Catholic School, also, selective state schools such as Handsworth Grammar School and King Edward VI Handsworth (girls).

Notable people

- James Watt (1736-1819), inventor and mechanical engineer, buried at St Mary's Church

- Joan Armatrading (born 1950), singer-songwriter and musician, grew up in the Brookfields area, since largely demolished and now part of Handsworth. She attended Canterbury Cross School

- Francis Asbury, born in Handsworth, bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church[12]

- Henry Barber, Birmingham businessman whose bequest founded the Barber Institute of Fine Arts

- Matthew Boulton (1728–1809), lived in Soho House, buried at St Mary's Church

- Roy Fisher (1930-2017), poet and jazz pianist

- David Hinds (born 1956), lead singer of reggae group Steel Pulse, grew up in Handsworth

- Tony Iommi, guitarist and founding member of heavy metal band Black Sabbath, was born in Handsworth[13]

- Carl Palmer (born 1950) drummer and percussionist. with bands including The Crazy World of Arthur Brown, Atomic Rooster, Emerson, Lake & Palmer, and Asia.

- Ian Emes, animator and film director

- Bert Freeman (1885–1955), England international footballer was born in Handsworth

- Mr Hudson, singer

- Apache Indian, dancehall artist

- Jimmy Moore, England international footballer was born in Handsworth

- William Murdoch (1754–1839), inventor. He was the first to make extensive use of coal gas for illumination and a pioneer in the development of steam-power. In 1777, he entered the engineering firm of Matthew Boulton and James Watt, whose experiment on the distillation of coal and wood first brought gas lighting to a practical stage, illuminating their factory with it in 1803. Presented with the Rumford Medal by the Royal Society. Buried at St Mary's Church

- George Ramsay (1855–1926), Secretary/Manager of Aston Villa in the most successful period of the club's history. Buried at St Mary's Church

- Tommy Roberts, professional footballer

- Albert Toft, sculptor

- Benjamin Zephaniah (born 1958), poet and writer, grew up in Handsworth

[[]]

References

- 1 2 "The Parish Boundaries of Handsworth". Handsworth Historical Society. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

- ↑ "Pubs in Peril". Historic Pub Interiors. Campaign for Real Ale. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ↑ Carl Chinn (1996) Brum Undaunted: Birmingham During the Blitz, Birmingham Library Services

- ↑ "Tram depot - Black Country Living Museum - Britain's friendliest open air museum". Bclm.co.uk. Retrieved 2012-07-29.

- ↑ Allen Edward Everitt. "Heathfield Hall, Handsworth". Birmingham Reference Library. Retrieved 2010-06-05.

- ↑ "George Tangye" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-06-05.

- ↑ Hugh Muir; Riazat Butt (24 October 2005). "A rumour, outrage and then a riot. How tension in a Birmingham suburb erupted". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ↑ "No-Go Britain: Where, what, why". 17 April 1994.

- ↑ "Anne Ziegler and Webster Booth". Showbiz Hall of Fame. BBC. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

- ↑ Rookery School

- ↑ Ofsted details for unique reference number 132138

- ↑ Who Was Who in America, Historical Volume, 1607-1896. Chicago: Marquis Who's Who. 1963.

- ↑ Iommi, Tony (8 November 2012). "Chapter 1: The birth of a Cub". Iron Man: My Journey Through Heaven and Hell with Black Sabbath. Simon & Schuster Ltd. ISBN 978-1849833219.

- Simon Baddeley (1997), The Founding of Handsworth Park 1882-1898, Birmingham University

- Carl Chinn (1996), Brum Undaunted: Birmingham During the Blitz, Birmingham Library Services

- Peter Drake (1998), Handsworth, Hockley, & Handsworth Wood, Tempus, Stroud, Glos.

- Allen E. Everitt (1876), Handsworth Church and its Surroundings, E.C. Osborne, Birmingham

- Frederick William Hackwood (1908), Handsworth: Old & New: A History of Birmingham's Staffordshire Suburb (re-published: A & B Books, Warley, West Midlands)

- John Morris Jones (1980), The Manor of Handsworth: An Introduction to its Historical Geography, with amendments by "Friends of Handsworth Old Town Hall", 1969. Handsworth Historical Society

- Handsworth General Purposes & other Committees - Minute Book 1880A, Handsworth Local Sanitary Board, Birmingham City Council, Central Library Archives (ref: BCH/AD 1/1/1)

- Handsworth & Birmingham newspaper cuttings collected and arranged by G. H. Osborne between approx. 1870 and 1900, Birmingham City Council, Central Library Archive (ref: L.f30.3)

- Victor J. Price (1992), Handsworth Remembered, Studley: Brewin Books

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Handsworth, West Midlands. |

- Birmingham City Council's Handsworth Ward pages

- Digital Handsworth

- Handsworth History

- Handsworth, West Midlands in the Domesday Book