Hammer

|

A modern claw hammer | |

| Types | Hand tool |

|---|---|

| Used with | Construction |

A hammer is a tool or device that delivers a blow (a sudden impact) to an object. Most hammers are hand tools used to drive nails, fit parts, forge metal, and break apart objects. Hammers vary in shape, size, and structure, depending on their purposes.

Hammers are basic tools in many trades. The usual features are a head (most often made of steel) and a handle (also called a helve or haft). Although most hammers are hand tools, powered versions exist; they are known as powered hammers. Types of power hammer include steam hammers and trip hammers, often for heavier uses, such as forging.

Some specialized hammers have other names, such as sledgehammer, mallet, and gavel. The term "hammer" also applies to devices that deliver blows, such as the hammer of a firearm, or the hammer of a piano, or the hammer ice scraper.

History

The use of simple hammers dates to around 3,300,000 BCE[1] [2] according to the 2012 find made by Sonia Harmand and Jason Lewis of Stony Brook University, who while excavating a site near Kenya's Lake Turkana discovered a very large deposit of various shaped stones including those used to strike wood, bone, or other stones to break them apart and shape them. Stones attached to sticks with strips of leather or animal sinew were being used as hammers with handles by about 30,000 BCE during the middle of the Paleolithic Stone Age.

The hammer's archeological record shows that it may be the oldest tool for which definite evidence exists of its early existence. [1].[2]

- A stone hammer found in Dover Township, Minnesota dated to 8000–3000 BCE, the North American Archaic period

Stone tapping hammer

Stone tapping hammer Perforated hammer head of stone

Perforated hammer head of stone Ancient Greek bronze sacrificial hammer, 7th century BCE, from Dodona

Ancient Greek bronze sacrificial hammer, 7th century BCE, from Dodona_hammer_crop.jpg) 16th-century claw hammer; detail from Dürer's Melencolia I (c. 1514)

16th-century claw hammer; detail from Dürer's Melencolia I (c. 1514)

Construction and materials

A traditional hand-held hammer consists of a separate head and a handle, fastened together by means of a special wedge made for the purpose, or by glue, or both. This two-piece design is often used, to combine a dense metallic striking head with a non-metallic mechanical-shock-absorbing handle (to reduce user fatigue from repeated strikes). If wood is used for the handle, it is often hickory or ash,[3] which are tough and long-lasting materials that can dissipate shock waves from the hammer head. Rigid fiberglass resin may be used for the handle; this material does not absorb water or decay, but does not dissipate shock as well as wood.

A loose hammer head is hazardous because it can literally "fly off the handle" when in use, becoming a dangerous uncontrolled missile. Wooden handles can often be replaced when worn or damaged; specialized kits are available covering a range of handle sizes and designs, plus special wedges for attachment.

Some hammers are one-piece designs made primarily of a single material. A one-piece metallic hammer may optionally have its handle coated or wrapped in a resilient material such as rubber, for improved grip and reduced user fatigue.[4]

The hammer head may be surfaced with a variety of materials, including brass, bronze, wood, plastic, rubber, or leather. Some hammers have interchangeable striking surfaces, which can be selected as needed or replaced when worn out.

Designs and variations

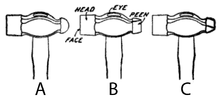

A large hammer-like tool is a maul (sometimes called a "beetle"), a wood- or rubber-headed hammer is a mallet, and a hammer-like tool with a cutting blade is usually called a hatchet. The essential part of a hammer is the head, a compact solid mass that is able to deliver a blow to the intended target without itself deforming. The impacting surface of the tool is usually flat or slightly rounded; the opposite end of the impacting mass may have a ball shape, as in the ball-peen hammer. Some upholstery hammers have a magnetized face, to pick up tacks. In the hatchet, the flat hammer head may be secondary to the cutting edge of the tool.

The impact between steel hammer heads and the objects being hit can create sparks, which may ignite flammable or explosive gases. These are a hazard in some industries such as underground coal mining (due to the presence of methane gas), or in other hazardous environments such as petroleum refineries and chemical plants. In these environments, a variety of non-sparking metal tools are used, primarily made of aluminium or beryllium copper. In recent years, the handles have been made of durable plastic or rubber, though wood is still widely used because of its shock-absorbing qualities and repairability.

Hand-powered hammers

- Ball-peen hammer,[5] or mechanic's hammer

- Boiler scaling hammer[5]

- Brass hammer, also known as non-sparking hammer or spark-proof hammer and used mainly in flammable areas like oil fields

- Carpenter's hammer (used for nailing), such as the framing hammer and the claw hammer, and pinhammers (ball-peen and cross-peen types) [5]

- Cow hammer – sometimes used for livestock slaughter, a practice now deprecated due to animal welfare objections[6]

- Cross-peen hammer,[5] having one round face and one wedge-peen face.

- Dead blow hammer delivers impact with very little recoil, often due to a hollow head filled with sand, lead shot or pellets

- Drilling hammer – a short handled sledgehammer originally used for drilling in rock with a chisel. The name usually refers to a hammer with a 2-to-4-pound (0.91 to 1.81 kg) head and a 10-inch (250 mm) handle, also called a "single-jack" hammer because it was used by one person drilling, holding the chisel in one hand and the hammer in the other.[7] In modern usage, the term is mostly interchangeable with "engineer's hammer", although it can indicate a version with a slightly shorter handle.

- Engineer's hammer, a short-handled hammer, originally an essential components of a railroad engineer's toolkit for working on steam locomotives.[8] Typical weight is 2–4 lbs (0.9–1.8 kg) with a 12–14 inch (30–35 cm) handle. Originally these were often cross-peen hammers, with one round face and one wedge-peen face, but in modern usage the term primarily refers to hammers with two round faces.

- Gavel, used by judges and presiding authorities to draw attention

- Geologist's hammer or rock pick

- Joiner's hammer, or Warrington hammer[5]

- Knife-edged hammer, its properties developed to aid a hammerer in the act of slicing whilst bludgeoning

- Lathe hammer (also known as a lath hammer, lathing hammer, or lathing hatchet), a tool used for cutting and nailing wood lath, which has a small hatchet blade on one side (with a small, lateral nick for pulling nails) and a hammer head on the other[9]

- Lump hammer, or club hammer

- Mallets, including versions made with hard rubber or rolled sheets of rawhide

- Railway track keying hammer[5]

- Rock climbing hammer

- Rounding hammer Blacksmith or farrier hammer. Round face generally for moving or drawing metal and flat for "planishing" or smoothing out the surface marks.

- Sledgehammer

- Soft-faced hammer

- Splitting maul

- Stonemason's hammer

- Tinner's hammer

- Upholstery hammer

- Welder's chipping hammer[5]

Mechanically-powered hammers

Mechanically-powered hammers often look quite different from the hand tools, but nevertheless most of them work on the same principle. They include:

- Hammer drill, that combines a jackhammer-like mechanism with a drill

- High Frequency Impact Treatment hammer — for aftertreatment of weld transitions

- Jackhammer

- Steam hammer

- Trip hammer

In professional framing carpentry, the manual hammer has almost been completely replaced by the nail gun. In professional upholstery, its chief competitor is the staple gun.

Tools used in conjunction with hammers

- Anvil

- Chisel

- Pipe drift (Blacksmithing - spreading a punched hole to proper size and/or shape)

- Star drill

- Punch

- Woodsplitting maul – can be hit with a sledgehammer for splitting wood.

- Woodsplitting wedge – hit with a sledgehammer for splitting wood.

Physics of hammering

Hammer as a force amplifier

A hammer is basically a force amplifier that works by converting mechanical work into kinetic energy and back.

In the swing that precedes each blow, the hammer head stores a certain amount of kinetic energy—equal to the length D of the swing times the force f produced by the muscles of the arm and by gravity. When the hammer strikes, the head is stopped by an opposite force coming from the target, equal and opposite to the force applied by the head to the target. If the target is a hard and heavy object, or if it is resting on some sort of anvil, the head can travel only a very short distance d before stopping. Since the stopping force F times that distance must be equal to the head's kinetic energy, it follows that F is much greater than the original driving force f—roughly, by a factor D/d. In this way, great strength is not needed to produce a force strong enough to bend steel, or crack the hardest stone.

Effect of the head's mass

The amount of energy delivered to the target by the hammer-blow is equivalent to one half the mass of the head times the square of the head's speed at the time of impact (). While the energy delivered to the target increases linearly with mass, it increases quadratically with the speed (see the effect of the handle, below). High tech titanium heads are lighter and allow for longer handles, thus increasing velocity and delivering the same energy with less arm fatigue than that of a heavier steel head hammer.[10] A titanium head has about 3% recoil energy and can result in greater efficiency and less fatigue when compared to a steel head with up to 30% recoil. Dead blow hammers use special rubber or steel shot to absorb recoil energy, rather than bouncing the hammer head after impact.

Effect of the handle

The handle of the hammer helps in several ways. It keeps the user's hands away from the point of impact. It provides a broad area that is better-suited for gripping by the hand. Most importantly, it allows the user to maximize the speed of the head on each blow. The primary constraint on additional handle length is the lack of space to swing the hammer. This is why sledge hammers, largely used in open spaces, can have handles that are much longer than a standard carpenter's hammer. The second most important constraint is more subtle. Even without considering the effects of fatigue, the longer the handle, the harder it is to guide the head of the hammer to its target at full speed.

Most designs are a compromise between practicality and energy efficiency. With too long a handle, the hammer is inefficient because it delivers force to the wrong place, off-target. With too short a handle, the hammer is inefficient because it doesn't deliver enough force, requiring more blows to complete a given task. Modifications have also been made with respect to the effect of the hammer on the user. Handles made of shock-absorbing materials or varying angles attempt to make it easier for the user to continue to wield this age-old device, even as nail guns and other powered drivers encroach on its traditional field of use.

As hammers must be used in many circumstances, where the position of the person using them cannot be taken for granted, trade-offs are made for the sake of practicality. In areas where one has plenty of room, a long handle with a heavy head (like a sledge hammer) can deliver the maximum amount of energy to the target. It is not practical to use such a large hammer for all tasks, however, and thus the overall design has been modified repeatedly to achieve the optimum utility in a wide variety of situations.

Effect of gravity

Gravity exerts a force on the hammer head. If hammering downwards, gravity increases the acceleration during the hammer stroke and increases the energy delivered with each blow. If hammering upwards, gravity reduces the acceleration during the hammer stroke and therefore reduces the energy delivered with each blow. Some hammering methods, such as traditional mechanical pile drivers, rely entirely on gravity for acceleration on the down stroke.

Ergonomics and injury risks

Both manual and powered hammers can cause peripheral neuropathy or a variety of other ailments when used improperly. Awkward handles can cause repetitive stress injury (RSI) to hand and arm joints, and uncontrolled shock waves from repeated impacts can injure nerves and the skeleton.

War hammers

A war hammer is a late medieval weapon of war intended for close combat action.

Symbolic hammers

The hammer, being one of the most used tools by Homo sapiens, has been used very much in symbols such as flags and heraldry. In the Middle Ages, it was used often in blacksmith guild logos, as well as in many family symbols. The hammer and pick is used as a symbol of mining.

A well known symbol with a hammer in it is the Hammer and Sickle, which was the symbol of the former Soviet Union and is very interlinked with communism and early socialism. The hammer in this symbol represents the industrial working class (and the sickle represents the agricultural working class). The hammer is used in some coat of arms in (former) socialist countries like East Germany. Similarly, the Hammer and Sword symbolizes Strasserism, a strand of National Socialism seeking to appeal to the working class.

The gavel, a small wooden mallet, is used to symbolize a mandate to preside over a meeting or judicial proceeding, and a graphic image of one is used as a symbol of legislative or judicial decision-making authority.

In Norse mythology, Thor, the god of thunder and lightning, wields a hammer named Mjölnir. Many artifacts of decorative hammers have been found, leading modern practitioners of this religion to often wear reproductions as a sign of their faith.

Judah Maccabee was nicknamed "The Hammer", possibly in recognition of his ferocity in battle. The name "Maccabee" may derive from the Aramaic maqqaba. (see Judah Maccabee § Origin of Name "The Hammer").

In American folklore, the hammer of John Henry represents the strength and endurance of a man.

The hammer in the song "If I Had a Hammer" represents a relentless message of justice broadcast across the land. The song became a symbol of the Civil Rights Movement.

Image gallery

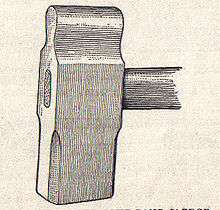

Dog-head hammer (blacksmithing)

Dog-head hammer (blacksmithing)

HiFIT-hammer for aftertreatment of weld transitions

HiFIT-hammer for aftertreatment of weld transitions Long cross-face hammer (blacksmithing)

Long cross-face hammer (blacksmithing) Post maul

Post maul Rubber mallet

Rubber mallet

Straight pane sledgehammer

Straight pane sledgehammer Twist hammer (blacksmithing)

Twist hammer (blacksmithing)

Wooden mallet

Wooden mallet

See also

References

- 1 2 Kate Wong (April 15, 2015). "Archaeologists Take Wrong Turn, Find World’s Oldest Stone Tools". Scientific American. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- 1 2 Sonia Harmand, Jason E. Lewis, Craig S. Feibel, Christopher J. Lepre, Sandrine Prat, Arnaud Lenoble, Xavier Boës, Rhonda L. Quinn, Michel Brenet, Adrian Arroyo, Nicholas Taylor, Sophie Clément, Guillaume Daver, Jean-Philip Brugal, Louise Leakey, Richard A. Mortlock, James D. Wright, Sammy Lokorodi, Christopher Kirwa, Dennis V. Kent & Hélène Roche (May 20, 2015). "3.3-million-year-old stone tools from Lomekwi 3, West Turkana, Kenya". Nature. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- ↑ What are some suitable woods to use for tool handles? - Woodworking Stack Exchange

- ↑ A beginner's guide to hammers / Boing Boing

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 British Standard BS 876:1995 Specification for Hand Hammers

- ↑ "Slaughter of livestock". FAO Corporate Document Repository. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 2015-07-10.

- ↑ "Tools for Pounding and Hammering". Retrieved 2014-08-03.

- ↑ Fish Ensie, E. (Feb 1909). "Handling Locomotive Supplies, Part III.--Standardization". American Engineer and Railway Journal: 55. Retrieved 2013-08-03.

- ↑ Farlex. Lathing hammer. The Free Dictionary.

- ↑ Cage, Chuck (2011-06-15). "DeWalt’s Titanium Hammer Killer?". Toolmonger. Retrieved 2013-04-18.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hammers. |

| Look up hammer in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Hammer types images and descriptions.

- The Hammer Museum

- "Choosing a Hammer". Popular Science, June 1960, pp. 164–167.