Hall's marriage theorem

Hall's marriage theorem, or simply Hall's theorem, proved by Philip Hall (1935), is a theorem with two equivalent formulations:

- The combinatorial mathematics formulation deals with a collection of finite sets. It gives a necessary and sufficient condition for being able to select a distinct element from each set.

- The graph theoretic formulation deals with a bipartite graph. It gives a necessary and sufficient condition for finding a matching that covers at least one side of the graph.

Combinatorial formulation

Let S be a family of finite sets, where the family may contain an infinite number of sets and the individual sets may be repeated multiple times.[1]

A transversal for S is a set T and a bijection f from T to S such that for all t in T, t is a member of f(t). An alternative term for transversal is system of distinct representatives.

The collection S satisfies the marriage condition if and only if for each subcollection , we have

In other words, the number of sets in each subcollection W is less than or equal to the number of distinct elements in the union over the subcollection W.

Hall's theorem states that S has a transversal if and only if S satisfies the marriage condition.

Examples

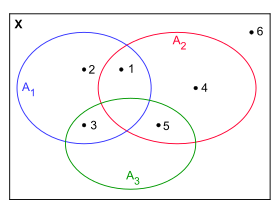

Example 1: Consider S = {A1, A2, A3} with

- A1 = {1, 2, 3}

- A2 = {1, 4, 5}

- A3 = {3, 5}.

A valid transversal would be (1, 4, 5). (Note this is not unique: (2, 1, 3) works equally well, for example.)

Example 2: Consider S = {A1, A2, A3, A4} with

- A1 = {2, 3, 4, 5}

- A2 = {4, 5}

- A3 = {5}

- A4 = {4}.

No valid transversal exists; the marriage condition is violated as is shown by the subcollection {A2, A3, A4}.

Example 3: Consider S= {A1, A2, A3, A4} with

- A1 = {a, b, c}

- A2 = {b, d}

- A3 = {a, b, d}

- A4 = {b, d}.

The only valid transversals are (c, b, a, d) and (c, d, a, b).

Application to marriage

The standard example of an application of the marriage theorem is to imagine two groups; one of n men, and one of n women. For each woman, there is a subset of the men, any one of which she would happily marry; and any man would be happy to marry a woman who wants to marry him. Consider whether it is possible to pair up (in marriage) the men and women so that every person is happy.

If we let Ai be the set of men that the i-th woman would be happy to marry, then the marriage theorem states that each woman can happily marry a man if and only if the collection of sets {Ai} meets the marriage condition.

Note that the marriage condition is that, for any subset of the women, the number of men whom at least one of the women would be happy to marry, , be at least as big as the number of women in that subset, . It is obvious that this condition is necessary, as if it does not hold, there are not enough men to share among the women. What is interesting is that it is also a sufficient condition.

Graph theoretic formulation

Let G be a finite bipartite graph with bipartite sets X and Y ( G:= (X + Y, E)). For a set W of vertices in X, let denote the neighborhood of W in G, i.e. the set of all vertices in Y adjacent to some element of W. The marriage theorem in this formulation states that there is a matching that entirely covers X if and only if for every subset W of X:

In other words: every subset W of X has sufficiently many adjacent vertices in Y.

Given a finite bipartite graph G:= (X + Y, E), with bipartite sets X and Y of equal size, the marriage theorem provides necessary and sufficient conditions for the existence of a perfect matching in the graph.

A generalization to general graphs (that are not necessarily bipartite) is provided by the Tutte theorem.

Proof of the graph theoretic version

An X-saturating matching is a matching which covers every vertex in X.

We first prove: If a bipartite graph G = (X + Y, E) = G(X, Y) has an X-saturating matching, then |NG(W)| ≥ |W| for all W ⊆ X.

Suppose M is a matching that saturates every vertex of X. Let the set of all vertices in Y matched by M to a given W be denoted as M(W). Therefore, |M(W)|=|W|, by the definition of matching. But M(W) ⊆ NG(W), since all elements of M(W) are neighbours of W. So, |NG(W)| ≥ |M(W)| and hence, |NG(W)| ≥ |W|.

Now we prove: If |NG(W)| ≥ |W| for all W ⊆ X, then G(X,Y) has a matching that saturates every vertex in X.

Assume for contradiction that G(X,Y) is a bipartite graph that has no matching that saturates all vertices of X. Let M be a maximum matching, and u a vertex not saturated by M. Consider all alternating paths (i.e., paths in G alternately using edges outside and inside M) starting from u. Let the set of all points in Y connected to u by these alternating paths be T, and the set of all points in X connected to u by these alternating paths (including u itself) be W. No maximal alternating path can end in a vertex in Y, lest it would be an augmenting path, so that we could augment M to a strictly larger matching by toggling the status (belongs to M or not) of all the edges of the path. Thus every vertex in T is matched by M to a vertex in W \ {u}. Conversely, every vertex v in W \ {u} is matched by M to a vertex in T (namely, the vertex preceding v on an alternating path ending at v). Thus, M provides a bijection of W \ {u} and T, which implies |W| = |T| + 1. On the other hand, NG(W) ⊆ T: let v in Y be connected to a vertex w in W. If the edge (w,v) is in M, then v is in T by the previous part of the proof, otherwise we can take an alternating path ending in w and extend it with v, getting an augmenting path and showing that v is in T. Hence, |NG(W)| = |T| = |W| − 1, a contradiction.

Equivalence of the combinatorial formulation and the graph-theoretic formulation

Let S = (A1, A2, ..., An) where the Ai are finite sets which need not be distinct. Let the set X = {A1, A2, ..., An} (that is, the set of names of the elements of S) and the set Y be the union of all the elements in all the Ai.

We form a finite bipartite graph G:= (X + Y, E), with bipartite sets X and Y by joining any element in Y to each Ai which it is a member of. A transversal of S is an X-saturating matching (a matching which covers every vertex in X) of the bipartite graph G. Thus a problem in the combinatorial formulation can be easily translated to a problem in the graph-theoretic formulation.

Marshall Hall Jr. variant

By examining Philip Hall's original proof carefully, Marshall Hall, Jr. (no relation to Philip Hall) was able to tweak the result in a way that permitted the proof to work for infinite S.[2] This variant refines the marriage theorem and provides a lower bound on the number of transversals that a given S may have. This variant is:[3]

Suppose that (A1, A2, ..., An), where the Ai are finite sets that need not be distinct, is a family of sets satisfying the marriage condition, and suppose that |Ai| ≥ r for i = 1, ..., n. Then the number of different transversals for the family is at least r ! if r ≤ n and r(r - 1) ... (r - n +1) if r > n.

Recall that a transversal for a family S is an ordered sequence, so two different transversals could have exactly the same elements. For instance, the family A1 = {1,2,3}, A2 = {1,2,5} has both (1,2) and (2,1) as distinct transversals.

Applications

The theorem has many other interesting "non-marital" applications. For example, take a standard deck of cards, and deal them out into 13 piles of 4 cards each. Then, using the marriage theorem, we can show that it is always possible to select exactly 1 card from each pile, such that the 13 selected cards contain exactly one card of each rank (Ace, 2, 3, ..., Queen, King).

More abstractly, let G be a group, and H be a finite subgroup of G. Then the marriage theorem can be used to show that there is a set T such that T is a transversal for both the set of left cosets and right cosets of H in G.

The marriage theorem is used in the usual proofs of the fact that an (r × n) Latin rectangle can always be extended to an ((r+1) × n) Latin rectangle when r < n, and so, ultimately to a Latin square.

Marriage condition does not extend

The following example, due to Marshall Hall, Jr., shows that the marriage condition will not guarantee the existence of a transversal in an infinite family in which infinite sets are allowed.

Let S be the family, A0 = {1, 2, 3, ...}, A1 = {1}, A2 = {2}, ..., Ai = {i}, ...

The marriage condition holds for this infinite family, but no transversal can be constructed.[4]

The more general problem of selecting a (not necessarily distinct) element from each of a collection of nonempty sets (without restriction as to the number of sets or the size of the sets) is permitted in general only if the axiom of choice is accepted.

Logical equivalences

This theorem is part of a collection of remarkably powerful theorems in combinatorics, all of which are related to each other in an informal sense in that it is more straightforward to prove one of these theorems from another of them than from first principles. These include:

- The König–Egerváry theorem (1931) (Dénes Kőnig, Jenő Egerváry)

- König's theorem[5]

- Menger's theorem (1927)

- The max-flow min-cut theorem (Ford–Fulkerson algorithm)

- The Birkhoff–Von Neumann theorem (1946)

- Dilworth's theorem.

In particular,[6][7] there are simple proofs of the implications Dilworth's theorem ⇔ Hall's theorem ⇔ König–Egerváry theorem ⇔ König's theorem.

Notes

- ↑ Hall, Jr. 1986, pg. 51. It is also possible to have infinite sets in the family, but the number of sets in the family must then be finite, counted with multiplicity. Only the situation of having an infinite number of sets while allowing infinite sets is not allowed.

- ↑ Hall, Jr. 1986, pg. 51

- ↑ Cameron 1994, pg.90

- ↑ Hall, Jr. 1986, pg. 51

- ↑ The naming of this theorem is inconsistent in the literature. There is the result concerning matchings in bipartite graphs and its interpretation as a covering of (0,1)-matrices. Hall, Jr. (1986) and van Lint & Wilson (1992) refer to the matrix form as König's theorem, while Roberts & Tesman (2009) refer to this version as the Kőnig-Egerváry theorem. The bipartite graph version is called Kőnig's theorem by Cameron (1994) and Roberts & Tesman (2009).

- ↑ Equivalence of seven major theorems in combinatorics

- ↑ Reichmeider 1984

References

- Brualdi, Richard A. (2010), Introductory Combinatorics, Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall/Pearson, ISBN 978-0-13-602040-0

- Cameron, Peter J. (1994), Combinatorics: Topics, Techniques, Algorithms, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-45761-0

- Dongchen, Jiang; Nipkow, Tobias (2010), "Hall's Marriage Theorem", The Archive of Formal Proofs, ISSN 2150-914X. Computer-checked proof.

- Hall, Jr., Marshall (1986), Combinatorial Theory (2nd ed.), New York: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0-471-09138-3

- Hall, Philip (1935), "On Representatives of Subsets", J. London Math. Soc., 10 (1): 26–30, doi:10.1112/jlms/s1-10.37.26

- Halmos, Paul R. and Vaughan, Herbert E. "The marriage problem". American Journal of Mathematics 72, (1950). 214–215.

- Reichmeider, P.F. (1984), The Equivalence of Some Combinatorial Matching Theorems, Polygonal Publishing House, ISBN 0-936428-09-0

- Roberts, Fred S.; Tesman, Barry (2009), Applied Combinatorics (2nd ed.), Boca Raton: CRC Press, ISBN 978-1-4200-9982-9

- van Lint, J. H.; Wilson, R.M. (1992), A Course in Combinatorics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-42260-4

External links

- Marriage Theorem at cut-the-knot

- Marriage Theorem and Algorithm at cut-the-knot

- Hall's marriage theorem explained intuitively at Lucky's notes.

This article incorporates material from proof of Hall's marriage theorem on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License.