Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict

| Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict | |

|---|---|

|

The distinctive marking of cultural property under the Hague Convention (Blue Shield). | |

| Signed | 14 May 1954 |

| Location | The Hague |

| Effective | 7 August 1956 |

| Parties | 128[1] |

| Depositary | Director-General of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization[1] |

| Languages | English, French, Russian and Spanish[1] |

The Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict is the first international treaty that focuses exclusively on the protection of cultural property in armed conflict. It was signed at The Hague, Netherlands on 14 May 1954 and entered into force on 7 August 1956. As of June 2017, it has been ratified by 128 states.[2]

The Hague Convention was adopted in the wake of the severe cultural destruction that occurred during the Second World War. Two Protocols to the Convention have been concluded. The First Protocol was introduced on 14 May 1954, and came into force on 7 August 1956. The Second Protocol was introduced on 26 March 1999, and came in force on 9 March 2004.

The Hague Convention covers immovable and movable cultural heritage including monuments, art, archaeological sites, scientific collections, manuscripts, books and other objects of artistic, historical or archaeological interest. The Convention seeks to safeguard the cultural property - and by extension the cultural legacy - of nations, groups and distinct members of society worldwide, from the consequences of armed conflict.[3]

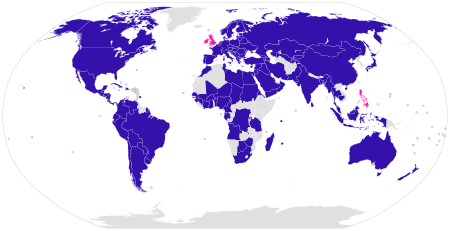

States parties

Party to the treaty | Signed but did not ratify |

As of June 2017, 128 states are party to the treaty, while three others (Andorra, Ireland and the Philippines)[4] have signed but not ratified the Convention. Currently, there are 105 States Parties to the First Protocol.[5] The Second Protocol has 72 States Parties.[6]

Cultural property

Cultural property is the manifestation and expression of the cultural heritage of a group of people or a society. It is an expression of the ways of living developed by a community and passed on from generation to generation, including the customs of a people, their practices, places, objects, artistic endeavours and values. The protection of cultural property during times of armed conflict or occupation is of great importance, because such property reflects the life, history and identity of communities; its preservation helps to rebuild communities, re-establish identities, and link people's past with their present and future. As stated in the Preamble to the Hague Convention, '... damage to cultural property belonging to any people whatsoever means damage to the cultural heritage of all mankind, since each people makes its contribution to the culture of the world'.[7]

The Hague Convention

The Hague Convention outlines various prohibitions and obligations which States Parties are expected to observe, both in peacetime and in times of conflict.

Broadly, the Hague Convention requires that States Parties adopt protection measures during peacetime for the safeguarding of cultural property. Such measures include the preparation of inventories, preparation for the removal of movable cultural property and the designation of competent authorities responsible for the safeguarding of cultural property.

States Parties undertake to respect cultural property, not only located within their own territory, but also within the territory of other States Parties, during times of conflict and occupation. In doing so, they agree to refrain from using cultural property and its immediate surroundings for purposes likely to expose it to destruction or damage in the event of armed conflict. States Parties also agree to refrain from any act of hostility directed against such property.

The Convention also requires the establishment of special units within national military forces, to be charged with responsibility for the protection of cultural property. Furthermore, States Parties are required to implement criminal sanctions for breaches of the Convention, and to undertake promotion of the Convention to the general public, cultural heritage professionals, the military and law-enforcement agencies.

An example of the successful implementation of the Hague Convention was the Gulf War, in which many members of the coalition forces (who were either party to the Convention or who, in the instance of the US, were not party to the Convention) accepted the Convention's rules, most notably by creating a “no-fire target list” of places where cultural property was known to exist.

Definition of cultural property

The Hague Convention defines 'cultural property' in Article 1, as follows:

'For the purposes of the present Convention, the term "cultural property" shall cover, irrespective of origin or ownership:

(a) movable or immovable property of great importance to the cultural heritage of every people, such as monuments of architecture, art or history, whether religious or secular; archaeological sites; groups of buildings which, as a whole, are of historical or artistic interest; works of art; manuscripts, books and other objects of artistic, historical or archaeological interest; as well as scientific collections and important collections of books or archives or of reproductions of the property defined above;

(b) buildings whose main and effective purpose is to preserve or exhibit the movable cultural property defined in sub-paragraph (a) such as museums, large libraries and depositories of archives, and refuges intended to shelter, in the event of armed conflict, the movable cultural property defined in subparagraph (a);

(c) centres containing a large amount of cultural property as defined in sub-paragraphs (a) and (b), to be known as "centres containing monuments".'[8]

Safeguarding cultural property

The obligation of States Parties to safeguard cultural property in peacetime is outlined in Article 3. It stipulates:

'The High Contracting Parties undertake to prepare in time of peace for the safeguarding of cultural property situated within their own territory against the foreseeable effects of an armed conflict, by taking such measures, as they consider appropriate.'[9]

Respect for cultural property

The Hague Convention sets out a minimum level of respect which all States Parties must observe, both in relation to their own national heritage as well as the heritage of other States Parties. States are obliged not to attack cultural property, nor to remove or misappropriate movable property from its territory of origin. Only exceptional cases of 'military necessity' will excuse derogation from this obligation. However, a State Party is not entitled to ignore the Convention's rules by reason of another Party's failure to implement safeguarding measures alone.

This is set out in Article 4 of the Hague Convention:

'Article 4:

(1) The High Contracting Parties undertake to respect cultural property situated within their own territory as well as within the territory of other High Contracting Parties by refraining from any use of the property and its immediate surroundings or of the appliances in use for its protection for purposes which are likely to expose it to destruction or damage in the event of armed conflict; and by refraining from any act of hostility directed against such property.

(2) The obligations mentioned in paragraph I of the present Article may be waived only in cases where military necessity imperatively requires such a waiver.

(3) The High Contracting Parties further undertake to prohibit, prevent and, if necessary, put a stop to any form of theft, pillage or misappropriation of, and any acts of vandalism directed against, cultural property. They shall, refrain from requisitioning movable cultural property situated in the territory of another High Contracting Party.

(4) They shall refrain from any act directed by way of reprisals against cultural property.

(5) No High Contracting Party may evade the obligations incumbent upon it under the present Article, in respect of another High Contracting Party, by reason of the fact that the latter has not applied the measures of safeguard referred to in Article 3.'[10]

Occupation

The rules set out in the Hague Convention also apply to States who are Occupying Powers of territory during conflict or otherwise. The Convention obliges Occupying Powers to respect the cultural property of the occupied territory, and to support local national authorities in its preservation and repair when necessary. This obligation is articulated in Article 5:

'Article 5:

(1) Any High Contracting Party in occupation of the whole or part of the territory of another High Contracting Party shall as far as possible support the competent national authorities of the occupied country in safeguarding and preserving its cultural property.

(2) Should it prove necessary to take measures to preserve cultural property situated in occupied territory and damaged by military operations, and should the competent national authorities be unable to take such measures, the Occupying Power shall, as far as possible, and in close co-operation with such authorities, take the most necessary measures of preservation.

(3) Any High Contracting Party whose government is considered their legitimate government by members of a resistance movement, shall, if possible, draw their attention to the obligation to comply with those provisions of the Conventions dealing with respect for cultural property.'[11]

Special protection

The Hague Convention establishes a 'special protection' regime, which obliges States Parties to ensure the immunity of cultural property under special protection from acts of hostility (Articles 8 and 9).[12] Under Article 8, this protection may be granted to one of three categories of cultural property: (1) refuges intended to shelter movable cultural property in the event of armed conflict; (2) centers containing monuments; and (3) other immovable cultural property of very great importance. To receive special protection, cultural property must also be located an adequate distance from an industrial center or location which would render it vulnerable to attack, and must not be used for military purposes.

First Protocol to the Hague Convention

The First Protocol was adopted at the same time as the Hague Convention, on 14 May 1954. It specifically applies to movable cultural property only, and prohibits the export of movable property from occupied territory and also requires its return to its original territory at the conclusion of hostilities (Article 1).[13] States Parties under the obligation to prevent the export of such property may be required to pay an indemnity to States whose property was removed during hostilities.

Second Protocol to the Hague Convention

Criminal acts committed against cultural property in the late 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s highlighted the deficiencies in the implementation of the Hague Convention and its First Protocol. As a result of the 'Boylan review' (a review of the Convention led by Professor Patrick Boylan),[14] the Second Protocol to the Hague Convention was adopted at a Diplomatic Conference held at The Hague in March 1999. The Second Protocol seeks complement and expand upon the provisions of the Hague Convention, by including developments in international humanitarian law and cultural property protection which had emerged since 1954. It builds on the provisions contained in the Convention relating to the safeguarding of and respect for cultural property, as well as the conduct of hostilities; thereby providing greater protection for cultural property than that conferred by the Hague Convention and its First Protocol.

Enhanced protection

One of the most important features of the Second Protocol is the 'enhanced protection' regime it establishes. This new category of cultural property is outlined in Chapter Three of the Second Protocol. Enhanced protection status means that the relevant cultural property must remain immune from military attack, once it is inscribed on the List of Cultural Property Under Enhanced Protection.[15] While the 1954 Hague Convention requires States not to make any cultural property the object of attack except for cases of 'military necessity', the Second Protocol stipulates that cultural property under enhanced protection must not be made a military target, even if it has (by its use) become a 'military objective'. An attack against cultural property which enjoys enhanced protection status is only excusable if such an attack is the 'only feasible means of terminating the use of property [in that way]' (Article 13).[16]

To be granted enhanced protection, the cultural property in question must satisfy the three criteria stipulated in Article 10 of the Second Protocol. The three conditions are:

(a) it is cultural heritage of the greatest importance for humanity;

(b) it is protected by adequate domestic legal and administrative measures recognising its exceptional cultural and historic value and ensuring the highest level of protection; and

(c) it is not used for military purposes or to shield military sites and a declaration has been made by the Party which has control over the cultural property, confirming that it will not be so used.[17]

Currently there are 12 cultural properties from 7 States Parties inscribed on the Enhanced Protection List. These include sites in Azerbaijan, Belgium, Cyprus, Georgia, Italy, Lithuania, and Mali.[18]

The Committee for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict

Article 24 of the Second Protocol establishes a 12-member Committee for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict. Its members are elected for a term of four years, and an equitable geographic representation is taken into account at the election of its members. The Committee meets once a year in ordinary session, and in extraordinary sessions if and when it deems necessary.

The Committee is responsible for the granting, suspension and cancellation of enhanced protection to cultural properties nominated by States Parties. It also receives and considers requests for international assistance which are submitted by States, as well as determining the use of the Fund for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict. Under Article 27 of the Second Protocol, the Committee also has a mandate to develop Guidelines for the implementation of the Second Protocol.

The Fund for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict

Article 29 of the Second Protocol establishes the Fund for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict. Its purpose is to provide financial or other assistance for 'preparatory or other measures to be taken in peacetime'. It also provides financial or other assistance in relation to 'emergency, provisional or other measures to protect cultural property during periods of armed conflict', or for recovery at the end of hostilities. The Fund consists of voluntary contributions from States Parties to the Second Protocol.[19] In 2016, the sums of US $50,000 and US $40,000 were provided to Libya and Mali respectively from the Fund, in response to their requests for assistance in the installation of emergency and safeguarding measures.[20]

Sanctions and individual criminal responsibility

Chapter Four of the Second Protocol specifies sanctions to be imposed for serious violations against cultural property, and defines the conditions in which individual criminal responsibility should apply. This reflects an increased effort to fight impunity through effective criminal prosecution since the adoption of the Hague Convention in 1954. The Second Protocol defines five 'serious violations' for which it establishes individual criminal responsibility (Article 15):[21]

- making cultural property under enhanced protection the object of attack;

- using cultural property under enhanced protection or its immediate surroundings in support of military action;

- extensive destruction or appropriation of cultural property protected under the Convention and this Protocol;

- making cultural property protected under the Convention and this Protocol the object of attack; and

- theft, pillage or misappropriation of, or acts of vandalism directed against cultural property protected under the Convention.

States are obligated to adopt appropriate legislation to make these violations criminal offences under their domestic legislation, to stipulate appropriate penalties for these offences, and to establish jurisdiction over these offences (including universal jurisdiction for three of the five serious violations, as set out in Article 16(1)(c)).[22]

An example of prosecution for crimes against cultural property is The Prosecutor v Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi case, handed down by the International Criminal Court on 27 September 2016. Al Mahdi was charged with and pleaded guilty to the war crime of intentionally directing attacks against historic monuments and buildings dedicated to religion, and sentenced to nine years' imprisonment.[23] Al Mahdi was a member of the Ansar Eddine group (a group associated with Al Qaeda), and a co-perpetrator of damaging and destroying nine mausoleums and one mosque in Timbuktu, Mali, in 2012.[23]

Military Manual

In 2016 UNESCO, in collaboration with the Sanremo International Institute of Humanitarian Law, published a manual titled 'Protection of Cultural Property: Military Manual'. This manual outlines the rules and obligations contained in the Second Protocol, and provides practical guidance on how these rules should be implemented by military forces around the world. It also contains suggestions as to best military practices in relation to these obligations. It relates only to the international laws governing armed conflict, and does not discuss military assistance that is provided in connection with other circumstances such as natural disasters.

World War II and degenerate art

_(Das_Wochen-_oder_Pfingst-Fest)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

The Nazi Party headed by Adolf Hitler rose to power in Germany in 1933 after the country's crippling defeat, and its socioeconomic distress during the years following World War I. World War II was aimed at reclaiming the glory of the once great Germanic state. Nothing was safe from Nazi Germany’s glare, with the first victim being cultural property of the European nations and the cultural property of significant groups located within them. The Nazi party through the “Third Reich confiscated close to 20% of all Western European art during the war. “By the end of the Second World War, the Nazi party looted at least one-third of all private art in France”.

Inherent within the Nazi’s ideology was the idea of supremacy of the Aryan Race and all that it produced; as such the Nazi campaign’s aims were to neutralize non-Germanic cultures and this was done through the destruction of culturally significant art and artifacts. This is illustrated greatest in the Jewish communities throughout Europe; by “devising a series of laws that allowed them to justify and regulate the legal confiscation of cultural and personal property. Within Germany the looting of German Jewish cultural property began with the confiscation of non-Germanic artwork in the German state collection. Degenerate art as it was known under the Nazi regime was deemed to be art which was not innately Germanic and which did not speak to Germanic culture, as such it was deemed to be worthless and slated for confiscation and destruction. Degenerate works of art were those whose subject, artist, or art was Jewish and as such offensive to the Third Reich.

Jewish collections were looted the most throughout the war. German Jews were ordered to report their personal assets, which were then privatized by the country. Jewish owned art galleries were forced to sell the works of art they housed. “The Nazis concentrated their efforts on ensuring that all art within Germany would be Aryan in nature, speaking to the might of the Germanic state rather than Jewish art which was deemed as a blight on society. Confiscation committees seized approximately 16,000 items, within Germany wherein following the purge, German museums were declared purified”. The remaining unexploited art was destroyed in massive bonfires. As the war progressed, the Nazi party elite ordered the confiscation of cultural property throughout various European countries.

Nazi plunder in Eastern Europe

In the Soviet Union, Nazi plunder of cultural significant art is best illustrated in the Third Reich's pillage of the Catherine Palace near St Petersburg and its famous Amber Room dating to the early 1700s. In October 1941, the Nazis had occupied the western portion of the Soviet Union, and began removing art treasures back to the west. The entirety of the Amber Room was removed to Königsberg and reconstructed there. In January 1945, with the Russian army advancing on the city, the Amber Room was order edto be moved again but its fate is thereafter unclear. A post-war Russian report concluded that 'summarizing all the facts, we can say that the Amber Room was destroyed between 9 and 11 April 1945' during the battle to take the city. However, in the absence of definitive proof, other theories about its fate continue to be entertained to the present day. With financial assistance from German donors, Russian craftsmen reconstructed a new Amber Room during the 1990s. The new room was dedicated by Russian President Vladimir Putin and German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder at the 300th anniversary of the city of Saint Petersburg.

After World War II

With the conclusion of the Second World War and the subsequent defeat of the Axis Powers, the atrocities which the Nazi leadership condoned, leading to the removal of culturally significant items and the destruction of numerous others could not be allowed to occur in future generations. This led the victorious Allied forces to create provisions to ensure safeguards for culturally significant items in times of war. As a result, in 1935 following the signature of the Roerich Pact by the American States in 1935 attempts were undertaken to draft a more comprehensive convention for the protection of monuments and works of art in time of war. In 1939, a draft convention, elaborated under the auspices of the International Museums Office, was presented to governments by the Netherlands. Due to the onset of the Second World War the draft convention was shelved with no further steps being taken. With the conclusion of the war, a new proposal was submitted to UNESCO by the Netherlands in 1948. The General Conference of UNESCO in 1951 decided to convene a committee of government experts to draft a convention. This committee met in 1952 and thereafter submitted its drafts to the General Conference. The intergovernmental Conference, which drew up and adopted the Convention and the further Acts, took place at The Hague from 21 April to 14 May 1954 where 56 States were represented. Following this international agreement The Hague Convention For the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict would come into force in 1956 in order to be an instrument of non derogation for the states bound by the document to stop the looting and destruction of cultural property

Siege of Dubrovnik 1991

From the time of its establishment the city of Dubrovnik was under the protection of the Byzantine Empire; after the Fourth Crusade the city came under the sovereignty of Venice 1205–1358 CE, and by the Treaty of Zadar in 1358, it became part of the Hungarian-Croatian Kingdom. Following the 1815 Congress of Vienna, the city was annexed by Austria and remained part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire until the conclusion of the First World War. From 1918 to 1939 Dubrovnik was part of the Zetska Banovina District that established its Croatian connections. From 1945 to 1990 Croatia would become part of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. One of the most striking features of the historic city of Dubrovnik, and that which gives its characteristic appearance are its intact medieval fortifications. Its historic city walls run uninterrupted encircling the Old-City. “This complex structure of fortification is one of the most complete depictions of medieval construction in the Mediterranean, consisting of a series of forts, bastions, casemates, towers and detached forts”. Within the Old City are many medieval churches, cathedrals, and palaces from the Baroque period, encircled by its fortified wall, which would ensure its listed place by UNESCO as a world heritage site in 1972. The Old Town is not only an architectural and urban ensemble of high quality, but it is also full of museums and libraries, such as the collection of the Ragusan masters in the Dominican Monastery, the Museum of the History of Dubrovnik, the Icon Museum, and the libraries of the Franciscan and Dominican Monasteries. It also houses the archives of Ragusa, which have been kept continuously since the 13th century and are “the most important source for Mediterranean history”. The archives hold materials created by the civil service in the Republic of Ragusa. The Siege of Dubrovnik was a military engagement fought between the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) and Croatian forces which defended the city of Dubrovnik and its surroundings during the Croatian War of Independence. The Old Town was specifically targeted by the JNA even though it served no military purpose to bomb this town. At the heart of the bombing efforts by the JNA elite was the complete eradication of the memory of the Croatian people and history by erasing their cultural heritage and destroying their cultural property.

Destruction of Mostar Bridge

.jpg)

The historic town of Mostar, spanning a deep valley of the Neretva River, developed in the 15th and 16th centuries as an Ottoman frontier town and during the Austro-Hungarian period in the 19th and 20th centuries. Mostar was mostly known for its old Turkish houses and specifically the Old Bridge; the Stari Mostar, after which it is named. In the 1990s conflict with the former Yugoslavia, however, most of the historic town and the Old Bridge were destroyed purposely by Croatian Army and their allies. This type of destruction was in step with that of the Old Town of Dubrovnik, where the aim was the eradication of the memory of the people that once occupied the land, an effort reminiscent of the Third Reich and the Nazi party.

Destruction of cultural heritage by ISIL

Deliberate destruction and theft of cultural heritage has been conducted by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant since 2014 in Iraq, Syria, and to a lesser extent in Libya. The destruction targets various places of worship under ISIL control and ancient historical artifacts. In Iraq, between the fall of Mosul in June 2014 and February 2015, ISIL has plundered and destroyed at least 28 historical religious buildings.[24] The valuable items from some buildings were looted in order to smuggle and sell them to finance ISIL activities.[24]

Although Libya, Syria and Iraq ratified the Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict in 1957, 1958 and 1967 respectively,[25] it has not been effectively enforced.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 (Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict - 1954 (information by UNESCO)

- ↑ http://www.unesco.org/eri/la/convention.asp?KO=13637&language=E&order=alpha

- ↑ http://www.unesco.org/new/en/culture/themes/armed-conflict-and-heritage/the-hague-convention/

- ↑ http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=13637&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html#STATE_PARTIES

- ↑ http://www.unesco.org/eri/la/convention.asp?KO=15391&language=E&order=alpha

- ↑ http://www.unesco.org/eri/la/convention.asp?KO=15391&language=E&order=alpha

- ↑ "Text | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization". www.unesco.org. Retrieved 2017-06-12.

- ↑ "Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict with Regulations for the Execution of the Convention". portal.unesco.org. Retrieved 2017-06-12.

- ↑ "Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict with Regulations for the Execution of the Convention". portal.unesco.org. Retrieved 2017-06-12.

- ↑ "Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict with Regulations for the Execution of the Convention". portal.unesco.org. Retrieved 2017-06-12.

- ↑ "Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict with Regulations for the Execution of the Convention". portal.unesco.org. Retrieved 2017-06-12.

- ↑ "Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict with Regulations for the Execution of the Convention". portal.unesco.org. Retrieved 2017-06-12.

- ↑ "Protocol to the Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed conflict". portal.unesco.org. Retrieved 2017-06-12.

- ↑ Boylan, Patrick J. "Review of the Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in Armed Conflict" (PDF).

- ↑ "Enhanced Protection | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization". www.unesco.org. Retrieved 2017-06-12.

- ↑ "Second Protocol to the Hague Convention of 1954 for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict". portal.unesco.org. Retrieved 2017-06-12.

- ↑ "Second Protocol to the Hague Convention of 1954 for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict". portal.unesco.org. Retrieved 2017-06-12.

- ↑ "Enhanced Protection | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization". www.unesco.org. Retrieved 2017-06-12.

- ↑ "Fund | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization". www.unesco.org. Retrieved 2017-06-12.

- ↑ "International Assistance | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization". www.unesco.org. Retrieved 2017-06-12.

- ↑ "Second Protocol to the Hague Convention of 1954 for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict". portal.unesco.org. Retrieved 2017-06-12.

- ↑ https://www.icrc.org/ihl/INTRO/590

- 1 2 International Criminal Court. "Case Information Sheet: The Prosecutor v Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi" (PDF).

- 1 2 Khalid al-Taie (13 February 2015). "Iraq churches, mosques under ISIL attack". mawtani.al-shorfa.com. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015.

- ↑ "Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict with Regulations for the Execution of the Convention. The Hague". UNESCO. 14 May 1954. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

References

- International Council on Monuments and Sites — Contains the full text of the Treaty

- Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict - 1954 (information by UNESCO)

- Text of the Convention at the Center for a World in Balance

- "Implementing the 1954 Hague Convention and its Protocols: legal and practical implications" Patrick J Boylan, City University London, UK Feb 2006]

- "THE DESTRUCTION OF CULTURAL PROPERTY DURING ARMED CONFLICT" ASSER INSTITUTE 16 December 2004

- U.S. Committee of the Blue Shield

- " International Humanitarian Law - Treaties & Documents" 2005

- " UNESCO "

Further reading

- Patrick J. Boylan, Review of the Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property for the Protection in the Event of Armed Conflict (The Hague Convention of 1954), Paris, UNESCO (1993), Report ref. CLT-93/WS/12.

- Jiri Toman, La protection des biens culturels en cas de conflit armé - Commentaire de la Convention de la Haye du 14 mai 1954, Paris, (1994).

- Fabio Maniscalco, Jus Praedae, Naples (1999).

- Fabio Maniscalco (ed.), Protection of Cultural Heritage in war areas, monographic collection "Mediterraneum", vol. 2 (2002).

- Fabio Maniscalco, World Heritage and War - monographic series "Mediterraneum", vol. VI, Naples (2007).

- Nout van Woudenberg & Liesbeth Lijnzaad (ed.). Protecting Cultural Property in Armed Conflict - An Insight into the 1999 Second Protocol to the Hague Convention of 1954 for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, publ. Martinus Nijhoff. Leiden - Boston (2010)

- Peter Barenboim, Naeem Sidiqi, Bruges, the Bridge between Civilizations: The 75 Anniversary of the Roerich Pact, Grid Belgium, 2010. ISBN 978-5-98856-114-9