Hadrian

| Hadrian | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Marble bust of Hadrian at the Palazzo dei Conservatori, Capitoline Museums. | |||||

| 14th Emperor of the Roman Empire | |||||

| Reign | 10 August 117 – 10 July 138 | ||||

| Predecessor | Trajan | ||||

| Successor | Antoninus Pius | ||||

| Born |

24 January 76 Italica, Hispania[1] (uncertain) | ||||

| Died |

10 July 138 (aged 62) Baiae | ||||

| Burial |

1) Puteoli 2) Gardens of Domitia 3) Hadrian's Mausoleum (Rome) | ||||

| Spouse | Vibia Sabina | ||||

| Issue |

Lucius Aelius (Adoptive), Antoninus Pius (Adoptive) | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Nervan-Antonine | ||||

| Father |

Publius Aelius Hadrianus Afer Trajan (Adoptive) | ||||

| Mother | Domitia Paulina | ||||

| ||||||||||||||

Hadrian (/ˈheɪdriən/; Latin: Publius Aelius Hadrianus Augustus;[note 1][2][note 2] 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. He is known for building Hadrian's Wall, which marked the northern limit of Britannia. He also rebuilt the Pantheon and constructed the Temple of Venus and Roma. Philhellene in most of his tastes, he is considered by some to have been a humanist, and he is regarded as the third of the Five Good Emperors.

Hadrian was born Publius Aelius Hadrianus into a Hispano-Roman family. Although Italica near Santiponce (in modern-day Spain) is often considered his birthplace, his actual place of birth remains uncertain. It is generally accepted that he came from a family with centuries-old roots in Hispania.[1][3] His predecessor, Trajan, was a maternal cousin of Hadrian's father.[4] Trajan did not designate an heir officially, but according to his wife Pompeia Plotina, he named Hadrian emperor immediately before his death. Trajan's wife and his friend Licinius Sura were well disposed towards Hadrian, and he may well have owed his succession to them.[5]

During his reign, Hadrian travelled to nearly every province of the Empire. An ardent admirer of Greece, he sought to make Athens the cultural capital of the Empire and ordered the construction of many opulent temples in the city. He used his relationship with his Greek lover Antinous to underline his philhellenism, and this led to the establishment of one of the most popular cults of ancient times. Hadrian spent a great deal of time with the military; he usually wore military attire and even dined and slept among the soldiers. He ordered rigorous military training and drilling and made use of false reports of attacks to keep the army on alert.

On his accession to the throne, Hadrian withdrew from Trajan's conquests in Mesopotamia, Assyria and Armenia, and even considered abandoning Dacia. Late in his reign he suppressed the Bar Kokhba revolt in Judaea, renaming the province Syria Palaestina. In 138 Hadrian adopted Antoninus Pius on the condition that he adopt Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus as his own heirs. They would eventually succeed Antoninus as co-emperors. Hadrian died the same year at Baiae.[6]

Sources

In Hadrian's time, there was already a well established convention that one could not write a contemporary Roman imperial history for fear of competing with the emperors themselves.[7] Information on the political history of Hadrian's reign comes mostly from later sources, some of them written centuries after the reign itself. A general account of Hadrian's reign is Book 69 of the early 3rd century Roman History by Cassius Dio. Dio's original Greek text for this book is lost; what survives is a brief, much later, Byzantine-era abridgment by the 11th century monk Xiphilinius. He selected from Dio's account of Hadrian's reign based on his mostly religious interests, covering the Bar Kokhba war relatively fully to the exclusion of much else. In Latin, Hadrian's biography is the first of the (probably late 4th century) collection of imperial biographies known as Historia Augusta. As this work is not only late, but notorious for its unreliability ("a mish mash of actual fact, cloak and dagger, sword and sandal, with a sprinkling of Ubu Roi"),[8] it cannot be used as a source without the utmost care. However, Hadrian's particular biography is generally considered by modern historians as relatively free of fictional additions, reflecting the existence of sound historical sources.[9] This sound source is generally assumed, on the basis of indirect evidence, to be the prominent 3rd century senator Marius Maximus, who wrote a now lost collection of imperial biographies from Nerva to Heliogabalus.[10]

As far as Hadrian's contemporaries are concerned, we have Greek authors such as Philostratus and Pausanias, who wrote shortly after Hadrian's reign. They did not write about definite political happenings, but had something to say about Hadrian's policies, i.e., the general framework that shaped Hadrian's decisions. These Greek authors are especially informative on Hadrian's relations with the provincial Greek world. A younger contemporary, Fronto, in his Latin correspondence, sheds some light on the general character of the reign's internal policies.[11] As in the case of all Antonine emperors, using epigraphical, numismatic, archaeological, and other non-literary sources is necessary in tracing a detailed, chronological account. Above all, without the use of the epigraphical evidence, a continuous account of Hadrian's reign is impossible. Hadrian's first modern historian, the German 19th century medievalist Ferdinand Gregorovius, was the first to make a serious effort at assembling a chronology of his voyages by studying the inscriptions then available.[12] Other modern historians, beginning with the German Ernst Kornemann, attempted to sort fact from fiction in the Historia Augusta biography, but achieved only doubtful results in the absence of alternative sources.[13]

Early life

Hadrian was born Publius Aelius Hadrianus in either Italica[14] or Rome,[15] into a well-established Roman family with centuries-old roots in Italica, Hispania Baetica, near modern Seville.

Although his family background made him "Spanish", his Historia Augusta biography states that he was born in Rome on 24 January 76, of an ethnically Hispanic family with vague paternal links to Italy. However, this may be a complimentary fiction coined to make Hadrian appear as a natural-born Roman instead of a provincial since his parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents were all born and raised in Hispania.[16] It was general knowledge that Hadrian and his predecessor Trajan were – in the words of Aurelius Victor – "aliens", people "from the outside" (advenae).[17]

Hadrian's father was Publius Aelius Hadrianus Afer, who as a senator of praetorian rank would spend much of his time in Rome, away from his homeland of Hispania.[18] Hadrian's known paternal ancestry can be partly linked to a family from Hadria, modern Atri, an ancient town in Picenum in Italy. This family had settled in Italica in Hispania Baetica soon after its founding by Scipio Africanus several centuries before Hadrian's birth. His father, Afer, was a paternal cousin of the Emperor Trajan. Both Afer and Trajan were born and raised in Hispania. His mother was Domitia Paulina, who came from Gades (Cádiz). Paulina was a daughter of a distinguished Hispano-Roman senatorial family.[19] His paternal great-grandmother is of unknown origin, meaning the exact amount of his paternal ancestry that can be linked to Italy (apart from nonspecific claims of forebears from Picenum from centuries earlier) is ultimately unknown.

Hadrian's elder sister and only sibling was Aelia Domitia Paulina, married to the triple consul Lucius Julius Ursus Servianus. His niece was Julia Serviana Paulina, and his great-nephew was Gnaeus Pedanius Fuscus Salinator, from Barcino (Barcelona). His parents died in 86 when Hadrian was ten, and he became a ward of both Trajan and Publius Acilius Attianus (who was later Trajan's Praetorian Prefect).[20] Hadrian was schooled in various subjects particular to young aristocrats of the day, and was so fond of learning Greek literature that he was nicknamed Graeculus ("Greekling").

Hadrian visited Italica when (or never left it until) he was 14 years old, when he was recalled by Trajan, who then looked after his development. He never returned to Italica although it was later made a colonia in his honour.[21]

Public service

Career up to the Dacian Wars

Hadrian's start at the vigintivirate (the minor posts whose holding qualified one for the senatorial career, cursus) was as one of the judges of the inheritance-court. Hadrian's first military service, in 95, was as a tribune of the Legio II Adiutrix. Exceptionally, he was then transferred to Legio V Macedonica and he held a second tribunate, and in such a capacity was chosen to inform Trajan of his adoption by Nerva. His choice as an envoy of his legion seems to have been decided by the then governor of Moesia Inferior, L.Julius Marinus.

As heir apparent to a frail and old emperor, Trajan had an obvious interest in being hedged by relatives and close friends. Therefore, Hadrian was retained in Germany – presumably on Trajan's orders – and was transferred to hold an even more exceptional third tribunate in Legio XXII Primigenia.[22] The fact that he had three spells of military service – instead of just one or two, as was customary for the regular senator – points to a thorough military career[23] and gave Hadrian an advantage, in terms of military expertise, over most scions from older senatorial families.[24] When Nerva died in 98, Hadrian rushed to inform Trajan personally, coming in advance of the official envoy sent by the governor, Hadrian's brother-in-law and rival Lucius Julius Ursus Servianus – but this may be a fiction coined by Hadrian himself.[25]

In 101 Hadrian began his senatorial career by being elected quaestor by the Senate, being then selected as quaestor imperatoris Traiani, acting as a liaison between the Curia and the Emperor. In such a capacity, he had the task of reading Trajan's speeches to the Senate – and possibly composing them himself. Next, he was ab actis senatus, charged with the task of keeping the Senate's record of its proceedings.[26] He was then created Tribune of the Plebs. From then on he began to be surrounded by stories about omens and portents that supposedly announced his future imperial condition.[27] According to the Historia Augusta, Hadrian had a great interest in astrology and divination and had been told of his future accession to the Empire by a grand-uncle who was himself a skilled astrologer.[28] It is also noteworthy that Trajan did not make Hadrian a Patrician, to allow him to become consul earlier, without having to hold the office of tribune.[29]

During the First Dacian War, Hadrian was a member of Trajan's personal entourage, being excused from his military post to take office in Rome as tribune of the plebs. After the war, it's probable that he was elected praetor in 104, assuming the post in 105.[30] At the time of the Second Dacian War, he was relieved early from Trajan's personal attendance, becoming legate of a legion – Legio I Minervia – and afterwards governor of Lower Pannonia.[31] Both were posts of praetorian rank. It's possible, therefore, that Hadrian was praetor in absentia, the dignity (as was generally the case with the old Republican magistracies during the Empire) being only a stepping stone qualifying him to fill higher posts.[32]

During both Dacian wars Hadrian developed a contradictory record as far as indications of Trajan's favour were concerned. At the same time he received the signal honour of assuming the tribunate of the plebs a year earlier than was customary and became a senator of praetorian rank, he was being consistently kept away from Trajan's innermost circle of advisers.[33] Perhaps an apt summary of the entire situation is an anecdote preserved by the Historia Augusta biography which states that, at about the same time, Hadrian received from Trajan the gift of a diamond ring that Trajan himself had received from Nerva, "and by this gift he [Hadrian] was encouraged in his hopes of succeeding to the throne".[34] Trajan was perhaps imitating the precedent set by Augustus in 23 BC, when a similar ring was handed to Agrippa as a token of his role as heir apparent.[35]

Relationship with Trajan and his family

What actually offered Hadrian a comparative advantage in the race for Trajan's succession were his connections to Trajan's female relatives. Around the time of his accession to the quaestorship, he married Trajan's grandniece, Vibia Sabina, in a move that seems to have been conceived by the empress Plotina, on whose favour he always counted. Plotina appears to have counted on Hadrian as a token of her future influence after Trajan's death, a way to avoid the political oblivion that befell her older contemporary, former empress Domitia Longina.[36] Plotina was a very learned woman with a philosophical upbringing, which meant that she and Hadrian shared interests that were political as well as intellectual, such as the idea of the Roman Empire as a commonwealth sharing a common Hellenic culture.[37]

As the prospects of Hadrian's rise were firstly a way to keep power in Trajan's family, by marrying Sabina Hadrian also counted on the support not only of Plotina, but of his mother in law, Trajan's niece Salonina Matidia.[38] Salonina Matidia was the daughter of Trajan's sister Ulpia Marciana, and therefore a hope for the survival of Trajan's dynasty by means of Trajan's female relatives.[39] Trajan himself, however, seems to have been far less enthusiastic about marrying his grandniece to Hadrian. The subsequent relationship between Hadrian and Sabina was exceptionally and scandalously poor, even for a marriage of convenience.[40]

Hadrian had tried to curry favor with Trajan by all means available, even indulging in Trajan's heavy drinking.[41] Nevertheless, sometime around his marriage to Sabina, he was involved in some unexplained quarrel told in Historia Augusta about his relationships with Trajan's boy favourites,[42] whom he had supposedly tried to groom.[43] All these circumstances might explain the downturn in Hadrian's fortunes late in Trajan's reign. Hadrian failed to achieve the honour of a regular consulate before his own reign, being only suffect consul for 108.[44] In short: after 108, Hadrian had become a consular – and therefore achieved parity with other members of the higher nobility – but not much else.[45] As much as Trajan surely actively promoted Hadrian's advancement, he did it in a very measured, careful way.[46]

%2C_Glyptothek%2C_Munich_(9014436520).jpg)

Nevertheless, when Sabina's grandmother Ulpia Marciana died between 112 and 114, she was deified by the Senate and her daughter Salonina Matidia made a "princess of the blood", an Augusta. This made Hadrian, late during Trajan's reign, the first senator in history to have an Augusta as his mother-in-law, something that his contemporaries could not fail to notice.[47]

It was then, in his mid-thirties, that Hadrian travelled to Greece, where he attended the lectures of the Stoic philosopher Epictetus, who lived in the city of Nicopolis.[48] He was also eponymous archon in Athens for a brief time, and was elected an Athenian citizen.[49] The Athenians awarded Hadrian a statue with an inscription in the Theater of Dionysus ( IG II2 3286) offering a detailed account of his cursus honorum, which confirms and expands the one in Historia Augusta.[50] Hadrian's career before Trajan's death was a regular one for a high ranking Roman senator, but without any particular distinction befitting an heir designate.[51] After the 112 Athenian archontate, no more is heard of Hadrian before Trajan's Parthian War, and it is possible that he remained in Greece until being summoned into the imperial retinue.[31]

His career before becoming emperor, as attested epigraphically in the Athens inscription, follows:

- decemvir stlitibus iudicandis

- sevir turmae equitum Romanorum

- praefectus Urbi feriarum Latinarum

- tribunus militum legionis II Adiutricis Piae Fidelis (95, in Pannonia Inferior)

- tribunus militum legionis V Macedonicae (96, in Moesia Inferior)

- tribunus militum legionis XXII Primigeniae Piae Fidelis (97, in Germania Superior)

- quaestor (101)

- ab actis senatus

- tribunus plebis (105)

- praetor (106)

- legatus legionis I Minerviae Piae Fidelis (106, in Germania Inferior)

- legatus Augusti pro praetore Pannoniae Inferioris (107)

- consul suffectus (108)

- septemvir epulonum (before 112)

- sodalis Augustalis (before 112)

- archon Athenis (112/13)

and afterwards

Hadrian was involved in the wars against the Dacians (as legate of the V Macedonica) and reputedly won awards from Trajan for his successes. During his 107 tenure as legate of Lower Pannonia, Historia Augusta credits him with the feat of "holding back the Sarmatians" – although we're not told precisely what is meant by "holding back".[53] Hadrian's military skill is not well-attested due to a lack of military action during his reign; however, his keen interest in, and knowledge of the army, and his demonstrated skill of leadership, show possible strategic talent.

Hadrian joined Trajan's expedition against Parthia as a legate on Trajan's staff.[54] Neither during the first victorious phase, nor during the second phase of the war when rebellion swept Mesopotamia, did Hadrian do anything of note. However, when the governor of Syria had to be sent to sort out renewed troubles in Dacia, Hadrian was appointed his replacement, giving him an independent command.[55]

By now seriously ill, Trajan decided to return to Rome while Hadrian remained in Syria to guard the Roman rear. In practical terms, Hadrian was now de facto general commander of the Eastern Roman army, something that made his power position as a potential claimant to the throne unchallengeable.[56] Trajan only got as far as Selinus before he became too ill to continue. While Hadrian may have been the obvious choice as successor, he had never been adopted as Trajan's heir. It is possible that Trajan never wanted to commit himself earlier with the appointment of a successor, as the great number of potential claimants made it conceivable that the definite choice of an heir would be seen as an abdication and thus lessening the chance for an orderly transmission of power.[57]

As Trajan lay dying, nursed by his wife, Plotina, and closely watched by Prefect Attianus, he could finally have adopted Hadrian as heir. Roman law admitted in certain cases, of testamentary adoption by means of a simple deathbed wish expressed before witnesses.[58] However, since the adoption document was signed by Plotina, it has been suggested that Trajan may have been dead already.[59] In a telltale sign, it has been discovered that Trajan's young manservant Phaedimus, in his late twenties, died a few days after Trajan's passing away in Selinus, and that his body was interred in Rome only twelve years later. As he was probably very close to Trajan, perhaps he was killed (or killed himself) for fear of being asked awkward questions.[60] Also, the recent discovery of an Aureus minted by Hadrian and presenting him as Caesar – i.e., heir designate – to Trajan (HADRIANO TRAIANO CAESARI) proves that Plotina and Hadrian had decided to make Trajan's adoption pass as official history.[61] Ancient sources were already divided about the actual happenings around Hadrian's adoption: Dio Cassius viewed the adoption as bogus; the Historia Augusta writer held the opposite position.[62]

Emperor (117)

Securing power

If Trajan's adoption of Hadrian was genuine, it came too late to dissuade other potential claimants.[64] Hadrian's rivals were Trajan's closest friends, the most experienced and senior members of the imperial council. Compared to them Hadrian was only an upstart.[65] Hadrian could not count on "inside" support from fellow senators, and had to find political friends elsewhere to secure his newly won position. According to Historia Augusta, Hadrian simply informed the Senate of his accession in a letter as a fait accompli, and that "the unseemly haste of the troops in acclaiming him emperor was due to the belief that the state could not be without an emperor".[66]

Hadrian quickly secured the support of the legions. One potential opponent, the Moorish prince and outstanding general Lusius Quietus, was promptly dismissed.[67] By taking his personal guard of Moorish auxiliaries from Quietus Hadrian could safely relieve him of his post as governor of Judea later.[68] The Senate's endorsement followed when possibly falsified papers of adoption from Trajan were presented. According to these papers, Hadrian had been adopted in absentia on 9 August 117 (Trajan having died on 8 August), which was technically irregular, as the two parties concerned were required to be present at the ceremony. The rumour of a falsified document of adoption carried little weight, as Hadrian's legitimacy arose from the endorsement of the Senate – and above all from the support of the Syrian armies.[69] Nevertheless, various public ceremonies were organized – Egyptian papyri tell of one organized between 117 and 118 CE – extolling the fact that Hadrian had been divinely chosen by his deified father and by the gods themselves.[70]

Hadrian did not go to Rome at first – he was engaged sorting out the East and suppressing the Jewish revolt that had broken out under Trajan. He then moved on to sort out the Danube frontier. Instead, Attianus, Hadrian's former guardian, was put in charge in Rome. There he "discovered" a conspiracy involving four leading senators including Lusius Quietus and demanded of the Senate their deaths.[71]

There was no question of a public trial – they were hunted down and killed out of hand. Since Hadrian was not in Rome at the time, he was able to claim that Attianus had acted on his own initiative. According to Elizabeth Speller, the real reason for their deaths was that they were Trajan's men.[71] Or better, all four were prominent senators of consular rank and, as such, were prospective candidates for the imperial office (capaces imperii).[72] Also, they were the chiefs of a war hawk group of senators who were committed to Trajan's expansionist policies, which Hadrian intended to change.[73] Besides Lusius Quietus, the consular Aulus Cornelius Palma was a former conqueror of Arabia Nabatea and as such had a stake in Trajan's Eastern policy.[74] (Hadrian's consistent refusal to expand frontiers was to remain a bone of contention between him and the Senate throughout his reign).[75] According to the Historia Augusta, Palma, as well as the third consular Lucius Publilius Celsus (consul for the second time in 113), were Hadrian's personal enemies and had spoken in public against him.[76] The fourth executed consular, Gaius Avidius Nigrinus, was an intellectual, friend of Pliny the Younger and briefly a Governor of Dacia at the start of Hadrian's reign. Nigrinus' ambiguous relationship with Hadrian would outlive him, having consequences late in the reign, when Hadrian had to plot his own succession.[77]

Hadrian's instrument for getting rid of the four consulars, Prefect Attianus, was made a senator and promoted to consular rank. He was later discarded by Hadrian, who suspected his personal ambition. It is probable that Attianus was executed (or was already dead) by the end of Hadrian's reign.[78] The four consulars episode strained Hadrian's relations with the Senate for his entire reign.[79] This tense relationship – and Hadrian's authoritarian stance towards the Senate – was acknowledged one generation later by Fronto, himself a senator, who wrote in one of his letters to Marcus Aurelius that "I praised the deified Hadrian, your grandfather, in the senate on a number of occasions with great enthusiasm, and I did this willingly, too [...] But, if it can be said – respectfully acknowledging your devotion towards your grandfather – I wanted to appease and assuage Hadrian as I would Mars Gradivus or Dis Pater, rather than to love him."[80] The strained relationship between Hadrian and the Senate never took the form of an overt confrontation as had happened during the reigns of previous "bad" emperors. Hadrian knew how to remain aloof to avoid an open clash.[81] The Senate's political role was effaced behind Hadrian's personal rule (in Ronald Syme's view. Hadrian "was a Führer, a Duce, a Caudillo").[82] The fact that Hadrian spent half of his reign away from Rome in constant travel undoubtedly helped the management of this strained relationship.[83] Hadrian underscored the autocratic character of his reign by counting the day of his acclamation by the armies as his dies imperiii, and legislating by frequent use of imperial decrees, to avoid having to seek the approval of the Senate.[84] According to Syme, Tacitus' description of the rise and accession of Tiberius is a disguised account of Hadrian's authoritarian Principate.[85] According, again, to Syme, Tacitus' Annals would be a work of contemporary history, written "during Hadrian's reign and hating it".[86]

Hadrian and the military

Despite his great reputation as a military administrator, a general lack of documented major military conflicts, apart from the Second Roman–Jewish War, marked Hadrian's reign. Disturbances on the Danubian frontier early in his reign led to the killing of the governor of Dacia, Caius Julius Quadratus Bassus. The consular Avidius Nigrinus served briefly as governor until Hadrian chose the then equestrian governor of Mauretania Caesariensis, Q. Marcius Turbo for the position. Turbo had a long record of distinguished military service and, as he was not a senator, could not act as a potential rival to Hadrian.[87] Turbo was made joint governor of Dacia and Pannonia Inferior with the powers of a Prefect.[88]

Hadrian soon decided that all the parts of Dacia that had been added to the province of Moesia Inferior – that is, present-day Southern Moldavia and the Wallachian Plain[89] – were to be surrendered to the Roxolani Sarmatians, whose king Rasparaganus received Roman citizenship, client king status, and possibly an increased subsidy. This partial withdrawal was probably supervised by the governor of Moesia Quintus Pompeius Falco.[90] Hadrian's presence on the Dacian front at this juncture, implied by the unreliable Historia Augusta, is merely conjectural. Hadrian did not visit Dacia during his later travels, but included it in his subsequent monetary series of coins with allegories of the provinces. So Eutropius' notion that Hadrian contemplated withdrawing from Dacia altogether appears to be unfounded.[91] The partial withdrawal probably had to do with the fact that the holding of the Eastern Dacian plains under Roman control would be far too expensive (involving the raising and deployment of several cavalry units as well as a network of fortifications) and therefore that it was more reasonable to leave the plains to be policed by a client ruler.[92]

Hadrian had already surrendered Trajan's conquests in Mesopotamia, considering them indefensible. In the East, he contented himself with retaining suzerainty over Osroene, ruled by the client king Parthamaspates, once client king of Parthia under Trajan.[93] There was almost a new war with Parthia around 121, but the threat was averted when Hadrian succeeded in negotiating a peace. Late in his reign (135), an invasion of the Alani in Capadocia, covertly supported by the king of Caucasian Iberia Pharasmanes, was successfully repulsed by Hadrian's governor, the historian Arrian.[94] He was a Greek intellectual and fellow student of Epictetus who had been appointed to the Senate by Hadrian and ruled Capadocia as imperial legate between 131 and 137.[95] After defeating the Alans, Arrian subsequently installed a Roman "adviser" in Iberia.[96] On all questions related to the Black Sea and the Caucasus, Arrian acted as Hadrian's chief adviser. Between 131 and 132 he sent Hadrian a lengthy letter (Periplus of the Euxine) on a maritime trip around the Black Sea, intended to offer relevant information in case of a Roman intervention.[97]

This abandonment of an aggressive policy was something which the Senate and its historians never forgave Hadrian: the 4th century historian Aurelius Victor charged him with being jealous of Trajan's exploits and deliberately trying to downplay their worthiness: Traiani gloriae invidens.[98] It is more probable that Hadrian simply considered the financial strain of a policy of conquests was something the Roman Empire could not afford. Proof of this is the disappearance during his reigns of two entire legions: Legio XXII Deiotariana and the famous "lost legion" IX Hispania, possibly destroyed during a late Trajanic uprising by the Brigantes in Britain.[99] Also, the acknowledgement of the indefensible character of the Mesopotamian conquests had perhaps already been made by Trajan himself, who had disengaged from them at the time of his death.[100]

The erection of permanent fortifications along the empire's borders (limites, sl. limes) strengthened the peace policy. The most famous of these is the massive Hadrian's Wall in Great Britain, built of stone and doubled on its rear by a ditch (Vallum Hadriani), which marked the boundary between a strictly military zone and the province.[101] A series of mostly wooden fortifications, forts, outposts and watchtowers, the latter specifically improving communications and local area security, strengthened the Danube and Rhine borders. These defensive activities are seldom mentioned in literary records. The information that Hadrian built the wall in Britain can only be found, in the entire corpus of ancient authors, in his Historia Augusta biography.[102] However, Hadrian's military activities were, in a certain measure, ideological, in that they emphasized a community of interests between all peoples living within the Roman Empire, instead of an hegemony of conquest centred on the city of Rome and its Senate.[103]

To maintain morale and prevent the troops from becoming restive, Hadrian established intensive drill routines, and personally inspected the armies. Although his coins showed military images almost as often as peaceful ones, Hadrian's policy was peace through strength, even threat,[104] with an emphasis on disciplina (discipline), which was the subject of two monetary series. This emphasis on spit and polish was heartily praised by Cassius Dio, who saw it as a useful deterrent and the reason for the generally peaceful character of Hadrian's reign.[105] Fronto expressed other opinions on the subject. In his view, Hadrian liked to play war games and enjoyed "giving eloquent speeches to the armies" – like the series of addresses, inscribed on a column that he made while on an inspection tour during 128 at the new headquarters of Legio III Augusta in Lambaesis[106] – and not actual warfare.[107] In general, Fronto was very critical of Hadrian's pacifist policy, blaming it for the decline in the military standards of the Roman army of his time.[108] Hadrian systematised employing the numeri – ethnic non-citizen troops with special weapons, such as Eastern mounted archers – in low-intensity defensive tasks such as dealing with infiltrators and skirmishers.[109] Using the numeri was an economical way to avoid frequent deployment of the legions, which suffered from a dearth of recruits from Italy as well as from the more Romanized provinces.[110] Hadrian is also credited with introducing units of cataphracts (heavy cavalry) into the Roman army.[111] This was the Ala I Gallorum et Pannoniorum catafracta[112]

Cultural pursuits and patronage

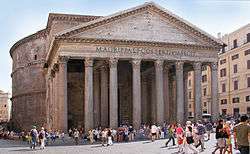

Hadrian was first described, in an ancient anonymous source later echoed by Ronald Syme, among others, as the most versatile of all the Roman Emperors (varius multiplex multiformis).[113] He liked to demonstrate his knowledge of all intellectual and artistic fields. Above all, Hadrian patronized the arts: Hadrian's Villa at Tibur (Tivoli) was the greatest Roman example of an Alexandrian garden, recreating a sacred landscape. (It was lost in large part to the despoliation of the ruins by the Cardinal d'Este, who had much of the marble removed to build Villa d'Este in the 16th century.) In Rome, the Pantheon, originally built by Agrippa and destroyed by fire in 80, was rebuilt under Hadrian (working from a blueprint left by Trajan: see below) in the domed form it retains to this day. It is among the best-preserved of Rome's ancient buildings and was highly influential to many of the great architects of the Italian Renaissance and Baroque periods.

From well before his reign, Hadrian displayed a keen interest in architecture, but it seems that his eagerness was not always well received. For example, Apollodorus of Damascus, famed architect of the Forum of Trajan, dismissed his designs. When Hadrian's predecessor, Trajan, consulted Apollodorus about an architectural problem, Hadrian interrupted to give advice, to which Apollodorus replied, "Go away and draw your pumpkins. You know nothing about these problems." "Pumpkins" refers to Hadrian's drawings of domes like the Serapeum in his villa. The historian Cassius Dio wrote that, once Hadrian succeeded Trajan and became emperor, he had Apollodorus exiled and later put to death. The story is problematical since archaeological evidence (brickstamps with consular dates) has demonstrated, e.g., that the Pantheon's dome was already under construction late in Trajan's reign (115) and probably under Apollodorus's sponsorship.[114]

Hadrian wrote poetry in both Latin and Greek; one of the few surviving examples is a Latin poem he reportedly composed on his deathbed (see below). Some of his Greek productions found their way into the Palatine Anthology.[115][116] He also wrote an autobiography, which Historia Augusta says was published under the name of Hadrian's freedman Phlegon of Tralles. It was not, apparently, a work of great length or revelation, but designed to scotch various rumours or explain Hadrian's most controversial actions.[117] It is possible that this autobiography had the form of a series of open letters to Antoninus Pius.[118]

According to one source, Hadrian was a passionate hunter from a young age.[119] In northwest Asia, he founded and dedicated a city to commemorate a she-bear he killed.[120] It is documented that in Egypt he and his beloved Antinous killed a lion.[120] In Rome, eight reliefs featuring Hadrian in different stages of hunting decorate a building that began as a monument celebrating a kill.[120]

Another of Hadrian's contributions to "popular" culture (in fact the generalised mores of the imperial elites) was the beard, which symbolised his philhellenism.[121] Dio of Prusa had equated the growth of the beard with the Hellenic ethos.[122] Since the time of Scipio Africanus it had been fashionable among the Romans to be clean-shaven. Also, all Roman emperors before Hadrian, except for Nero (also a great admirer of Greek culture), were clean-shaven. Most of the emperors after Hadrian would be portrayed with beards. However, their beards were not worn out of an appreciation for Greek culture but because the beard had become fashionable, thanks to Hadrian. This new fashion lasted until the reign of Constantine the Great[123] and was revived again by Phocas at the start of the 7th century.[124] Notwithstanding his philhellenism, in all other everyday life matters Hadrian behaved as a Roman civic traditionalist, who demanded senators and knights use the toga in public, and strict separation between the sexes in public baths and theatres.[125]

As a cultural Hellenophile Hadrian was familiar with the work of the philosophers Epictetus, Heliodorus and Favorinus. At home, he attended to social needs. Hadrian mitigated slavery: masters were forbidden from killing their slaves unless allowed by a court to punish them for a grave offense.[126] Masters were forbidden to sell slaves to a gladiator trainer (lanista) or to a procurer, except as justified punishment.[127] Hadrian also had the legal code humanised and forbade torture of free defendants and witnesses, legislating against the common practice of condemning free persons to have them tortured to gather information on their supposed activities and accomplices.[128] He also abolished ergastula, private prisons for slaves in which kidnapped free men could also be kept.[129]

Hadrian's humanitarian views had a limit, namely, the existence of slavery itself. When confronted by a crowd demanding the freeing of a popular slave charioteer, he replied that he could not free a slave belonging to another person.[130] Also, Hadrian at least once personally engaged in cruelty toward a slave: in a fit of rage, he stabbed the eye of one of his secretaries with a pen.[131]

He built libraries, aqueducts, baths and theatres. Hadrian is considered by many historians to have been wise and just. Schiller called him "the Empire's first servant", and British historian Edward Gibbon admired his "vast and active genius", as well as his "equity and moderation". In 1776, he stated that Hadrian's era was part of the "happiest era of human history".

While visiting Greece in 131–132, Hadrian attempted to create a kind of provincial parliament to bind all the semi-autonomous former city states across all Greece and Ionia (in Asia Minor). This parliament, known as the Panhellenion, is generally conceived as a failed, albeit spirited, effort to foster cooperation among the Hellenes. However, as the German sociologist Georg Simmel remarked, the aim of the Panhellenion was probably to render Hellenism inert: to divert the feeling of a common Hellenic identity towards ideal purposes: "games, commemorations, preservation of an ideal, an entirely non-political Hellenism".[132]

Hadrian died at his villa in Baiae. He was interred in a mausoleum on the western bank of the Tiber, in Rome, in a building later transformed into a papal fortress, Castel Sant'Angelo. The dimensions of his mausoleum, in its original form, were deliberately designed to be slightly larger than the earlier Mausoleum of Augustus.

According to Cassius Dio, a gigantic equestrian statue was erected to Hadrian after his death. "It was so large that the bulkiest man could walk through the eye of each horse, yet because of the extreme height of the foundation persons passing along on the ground below believe that the horses themselves as well as Hadrian are very very small." This may refer to the huge statuary group placed atop the mausoleum depicting Hadrian driving a four-horse quadriga chariot, which disappeared at some later time.

Hadrian's travels

Purpose

The most distinctive aspect of Hadrian's reign was that he was to spend more than half of it outside Italy and engaged in peaceful pursuits. Obviously, other emperors had often left Rome for long periods, but then mostly to go to war, returning soon after conflicts concluded. A previous emperor, Nero, once travelled through Greece and was condemned for his self-indulgence. According to modern historians such as Paul Veyne, what Hadrian intended by his incessant travelling was to break with the sedentary (casanière) tradition of earlier emperors, who saw the Empire as a purely Roman hegemony – something Nero had failed to achieve. Hadrian sought to make his subjects feel part of a commonwealth of civilized peoples, sharing a common Hellenic culture.[133] That is why, in a speech to the Senate preserved by Aulus Gellius, he supported the creation of new municipia, autonomous urban communities with their own customs and laws, over the formation of new colonies with a standard Roman-type constitution .[134]

All this did not go well with Roman traditionalism. As far as the Historia Augusta portrays traditional ideology, Hadrian was regarded by its author as "a little too much Greek", far more cosmopolitan than it was thought fit for a Roman emperor.[135] The significance of Hadrian's travels to stress the cosmopolitan, ecumenical character of the Roman Empire was confirmed late during his reign when he struck a series of special issue coins representing allegories of the various provinces.[136]

Hadrian travelled as an integral part of his governing, something he made clear to the Roman Senate and the people. To check the Roman populace, he made recourse to his chief equestrian adviser, Marcius Turbo, who was made Pretorian Prefect in 121 – while he was still joint-governor of Dacia and Pannonia Inferior[137] – and was tasked with adjudicating non-senators. As a procurator,[138] Turbo was already regarded as one of the leading men of the equestrian order.[139] Nonetheless, he was not qualified to keep a check on the Senate, as Hadrian forbade equestrians to try cases against senators.[140] The Senate had ultimate legal authority over its members, as it remained formally the highest court of appeal, from which appealing to the Emperor was forbidden.[141] There are hints within certain sources that Hadrian also employed a secret police force, the frumentarii, on an ad hoc, occasional basis[142] to snoop primarily on people of high social standing, such as his close friends.[143]

His visits were marked by handouts that often contained instructions for the construction of new public buildings. His intention was to strengthen the Empire from within through improved infrastructure, as opposed to conquering or annexing perceived enemies. This was often the purpose of his journeys; commissioning new structures, projects and settlements. His almost evangelical belief in Greek culture strengthened his views. Like many emperors before him, Hadrian's will was almost always obeyed.[144] Later, the Greek rhetorician Aelius Aristides was to extol Hadrian's activities writing that he "extended over his subjects a protecting hand, raising them as one helps fallen men on their feet".[145]

His travelling court was large, including administrators and probably also architects and builders. The burden on the areas he passed through was sometimes great. While his arrival usually brought some benefits, it is possible that those who had to bear the burden were of a different class from those who reaped the benefits. For example, huge amounts of provisions were requisitioned during his visit to Egypt; this suggests that the burden on the mainly subsistence farmers must have been intolerable, causing some measure of starvation and hardship.[144]

At the same time, as in later times all the way through the European Renaissance, kings were welcomed into their cities or lands, and the financial burden was completely on them, and only indirectly on the poorer class. Hadrian's first tour came just four years after assuming the office of Caesar, when he sought a cure for a skin disease thought to be leprosy and travelled to Judea while en route to Egypt.[146] This time also allowed him the freedom to concern himself with his general cultural aims. At some point, he travelled north, towards Germania and inspected the Rhine–Danube frontier, allocating funds to improve the defences. It was a voyage to the Empire's very frontiers that represented perhaps his most significant visit; upon hearing of a recent revolt, he journeyed to Britannia.

Britannia and the West (122)

Prior to Hadrian's arrival in Britain, there had been a major rebellion in Britannia from 119 to 121.[147] Although operations in Britannia at the time got no mention worthy of note in the literary sources, inscriptions tell of an expeditio Britannica involving major troop movements, including sending a vexillatio (i.e., a detachment) of some 3,000 men taken from legions stationed on the Rhine and in Spain; Fronto writes about military losses in Britannia at the time.[148] The Historia Augusta notes that the Britons could not be kept under Roman control; Pompeius Falco was sent to Britain to restore order, and coins of 119–120 refer to this. In 122 Hadrian initiated the construction of Hadrian's Wall. It was built "to separate Romans from barbarians", according to the Historia Augusta.[149] It deterred attacks on Roman territory at a lower cost than a massed border army,[150] and controlled cross-border trade and immigration.[151]

Unlike the Germanic limes, built of wood palisades, Hadrian's Wall was primarily a stone construction.[152] The western third of the wall, from modern-day Carlisle, Cumbria to the River Irthing, was originally built of turf for unknown reasons. Possibly to hasten its construction, the wall's width was narrowed in some sections from the original planned 12 feet (3.7 m) to 7 feet (2.1 m) . The turf wall was later rebuilt in stone, and a large ditch with adjoining mounds, known today as the Vallum, was dug to the south of the wall.[153]

Under Hadrian, a shrine was erected in York to Britain as a goddess, and coins that introduced a female figure as the personification of Britain, labelled BRITANNIA, were struck.[154] By the end of 122, Hadrian had concluded his visit to Britannia, and from there headed south to Mauretania, never to return. He never saw the finished wall that bears his name.

Hadrian appears to have gone to Mauretania through southern Gaul, and it is probable that he visited Nemausus, where he may have overseen the building of a basilica dedicated to Plotina, who had meanwhile died in Rome. Plotina was in due course deified at Hadrian's prompting.[155] Shortly before her death, he had already granted Plotina a signal favour, by stating that succession to the head of the Epicurean School in Athens could be granted to a non-Roman citizen – a petition made by the incumbent head of the school seeking Plotina's intercession.[156] Matidia Augusta, Hadrian's mother-in-law, had died earlier, in December 119, and had also been deified.[157] The deification of these prominent female members of Trajan's family might be seen as an effort by Hadrian to buttress his legitimacy.[158] At what appears to have been the same time, Hadrian dismissed his secretary in charge of his official correspondence (ab epistulis), the historian Suetonius, for "excessive familiarity" towards the empress.[159] Also dismissed for the same alleged reason was Marcius Turbo's colleague as Praetorian Prefect, Gaius Septicius Clarus. Given Clarus' high office, the alleged reason for his dismissal could have been merely a pretext to remove him from office.[160]

Hadrian spent the winter of 122/123 at Spain, in Tarraco, where he restored the Temple of Augustus before crossing the Mediterranean into Mauretania.[161]

Africa, Parthia and Anatolia; Antinous (123–124)

In 123, Hadrian arrived in Mauretania where he personally led a campaign against local rebels.[162] This visit was short, as reports came through that the eastern nation of Parthia was again preparing for war; as a result, Hadrian quickly headed eastwards. On his journey east it is known that at some point he visited Cyrene, during which time he personally made available funds for the training of the young men of well-bred families for the Roman military. Cyrene had benefited earlier from his generosity when he provided funds in 119 for the rebuilding of public buildings destroyed during the recent Jewish revolt.[163] The rebuilding lasted until late in the reign, and in 138 a statue of Zeus was erected with a dedication to Hadrian as "saviour and founder" of Cyrene.[164]

When Hadrian arrived on the Euphrates, he characteristically solved the problem through a negotiated settlement with the Parthian King Osroes I. He then proceeded to check the Roman defences before setting off west along the coast of the Black Sea.[165] He probably spent the winter in Nicomedia, the main city of Bithynia. As Nicomedia had been hit by an earthquake only shortly before his stay, Hadrian was generous in providing funds for rebuilding, for which he was acclaimed as the chief restorer of the province.[166]

It is possible that Hadrian visited Claudiopolis and saw the beautiful Antinous, a boy destined to become his beloved. Sources say nothing about when Hadrian met him. There are depictions of Antinous that show him as a young man of 20 or so. As this was shortly before his death in 130 (the earliest date for which we can be sure of Antinous' being together with Hadrian) in 123 he would most likely have been a youth of 13 or 14.[166] It is possible that Antinous was sent to Rome to be trained as a page to serve the emperor and only gradually rose to the status of imperial favourite.[167] The actual history of their relationship is mostly unknown.[168]

With or without Antinous, Hadrian travelled through Anatolia. The route he took is uncertain. Various incidents are described, such as his founding of a city within Mysia, Hadrianutherae, after a successful boar hunt. (The building of the city was probably more than a mere whim – sparsely populated wooded areas such as the site of the new city were already ripe for development). Some historians dispute whether Hadrian did in fact commission the city's construction at all. At about this time, plans to complete the Temple of Zeus in Cyzicus, begun by the kings of Pergamon, were put into practice. The temple, whose completion had been contemplated by Trajan, received a colossal statue of Hadrian, and was built with dazzling white marble with gold thread. Cyzicus received the added honor of being declared a regional centre for the Imperial cult (neocoros), sharing it with Pergamon, Smyrna, Ephesus and Sardes[169] – something that offered the benefits of Imperial sponsorship of sacred games, attracting tourism, and stimulating private expenditure, as well as channelling intercity rivalry into a common acceptance of Roman rule.[170]

Greece (124–125)

Continuing his tour, Hadrian arrived in the autumn of 124 in time to participate in the Eleusinian Mysteries. By tradition, at one stage in the ceremony the initiates were supposed to carry arms; this was waived to avoid any risk to the emperor. At the Athenians' request, he revised their constitution – among other things, a new phyle (tribe) was added bearing his name.[171] Also, a system of coercive purchases of oil was imposed on Athenian producers to ensure an adequate supply of the commodity; management of the system was left in the hands of the local Assembly and Council, appeals to the Emperor notwithstanding.[172] Athens also became the only provincial city to benefit from a regular supply of grain.[173] Hadrian also created two foundations to provide for the funding of Athens' public games, whenever there was no citizen wealthy enough (or willing) to sponsor them as a Gymnasiarch or Agonothetes.[174] Generally Hadrian preferred that civic expenditure by Greek notables should concentrate on buildings rather than on spectacles and competitions. In a letter to Aphrodisias he praised a requirement that high priests of the imperial cult donate funds to work on an aqueduct not to gladiatorial games.[175] Such aqueducts – associated with public fountains – nymphaea – were one of Hadrian's additions to the Greek urban landscape: besides Athens, where two such fountains were built, Argos also received a similar project.[176]

According to Eusebius, it was possibly at this time that Hadrian received an apology (i.e., a defense) of the Christian faith made by two Christians, Quadratus and Aristides. Apparently, Hadrian simply kept to Trajan's policy of passive tolerance, by which Christians should not be sought after, but sentenced only after due trial.[177] In a rescript addressed to the proconsul of Asia Minutius Fundanus and preserved by Justin Martyr, Hadrian laid down that accusers of Christians had to bear the burden of proof for their denunciations[178] on pain of being punished for calumnia (defamation).[179]

During the winter he toured the Peloponnese. His exact route is uncertain, but Pausanias reports of telltale signs, such as temples built by Hadrian and the statue of the emperor – in heroic nudity – built by the grateful citizens of Epidaurus[180] in thanks to their "restorer". He was especially generous to Mantinea, where he restored the Temple of Poseidon Hippios; this supports the theory that Antinous was in fact already Hadrian's lover because of the strong link between Mantinea and Antinous's home in Bithynia.[181] As this kinship between Mantinea and Bythinia was itself a mythological fiction of the kind used at the time for encouraging political alliances between polities, a more serious reason might exist for Hadrian's particular generosity.[182] Hadrian's buildings in Greece were no mere whims, as they followed a pattern of favoring old religious centers. Besides the temple at Mantinea, Hadrian restored other ancient shrines in Abae, Argos – where he restored the Heraion – and Megara.[183] This was a way of gathering legitimacy to Roman imperial rule by associating it with the glories of classical Greece – something well in line with contemporary antiquarian taste in cultural matters.[184] Pausanias credits Hadrian with restoring to Mantinea its ancient, classical name. It had been named Antigoneia since Hellenistic times, in honour of the Macedonian King Antigonus III Doson.[185]

This same idea of resurrecting the classical past under Roman overlordship was behind the possibility that, during his tour of the Peloponnese, Hadrian persuaded the Spartan grandee Eurycles Herculanus – the contemporary leader of the Euryclid family that had ruled Sparta since Augustus' day – to enter the Senate, alongside the Athenian grandee Herodes Atticus the Elder. The two aristocrats would be the first Greeks from Old Greece to enter the Roman Senate, as "representatives" of the two "great powers" of the Classical Age.[186] This was an important step in overcoming Greek notables' haughty disdain and their reluctance to take part in Roman political life.[187]

By March 125, Hadrian had reached Athens, presiding over the festival of Dionysia. The building program that Hadrian initiated was substantial. Various rulers had done work on building the Temple of Olympian Zeus over a time span of more than five centuries – it was Hadrian and the vast resources he could command that ensured that the job would be finished. He also initiated the construction of several public buildings on his own whim and even organized the building of an aqueduct.[188]

Return to Italy and trip to Africa (126–128)

On his return to Italy, Hadrian made a detour to Sicily. Coins celebrate him as the restorer of the island, though there is no record of what he did to earn this accolade.[189]

Back in Rome, he was able to see for himself the completed work of rebuilding the Pantheon. Hadrian's villa nearby at Tibur, a retreat by the Sabine Hills, was also completed. At the beginning of March 127 Hadrian set off for a tour of Italy. Once again, historians are able to reconstruct his route by evidence of his hand-outs rather than from historical records.[190]

For instance, in that year he restored the Picentine earth goddess Cupra in the town of Cupra Maritima. At some unspecified time, he improved the drainage of the Fucine lake. Less welcome than such largesse was his decision in 127 to divide Italy into four regions under imperial legates with consular rank, who had jurisdiction over all of Italy excluding Rome itself, therefore shifting cases from the courts of Rome.[191] Actually, the four consulars acted as governors of the regions assigned to them. Having Italy effectively reduced to the status of a group of mere provinces did not go down well with Italian hegemonic feelings (especially with the Roman Senate),[192] and this innovation did not long outlive Hadrian.[190]

Hadrian fell ill around this time, though the nature of his sickness is not known. Whatever it was, it did not stop him from setting off in the spring of 128 to visit Africa. His arrival began with the good omen of rain ending a drought. Along with his usual role as benefactor and restorer, he found time to inspect the troops; his speech to the troops survives to this day.[193] Hadrian returned to Italy in the summer of 128 but his stay was brief, as he set off on another tour that would last three years.[194]

Greece, Asia, and Egypt (128–130); Antinous's death

%2C_Athens_(14038051163).jpg)

In September 128, Hadrian attended the Eleusinian mysteries again. This time his visit to Greece seems to have concentrated on Athens and Sparta – the two ancient rivals for dominance of Greece. Hadrian had played with the idea of focusing his Greek revival around the Amphictyonic League based in Delphi, but by now he had decided on something far grander. His new Panhellenion was going to be a council that would bring Greek cities together. The meeting place was to be the new temple to Zeus in Athens. Having set in motion the preparations – deciding whose claim to be a Greek city was genuine would take time – Hadrian set off for Ephesus.[195] The notion of the "Greek city" was mostly political and mythological rather than historical. It involved fabricated claims to Greek origins and imperial favour.[196] Most importantly, it linked appreciation of an idealized cultural Hellenism with loyalty to Rome and her Emperor.[197] The Panhellenion was devised with a view to associating the Roman Emperor with the protection of Greek culture and of the "liberties" of Greece – in this case, urban self-government. It allowed Hadrian to appear as the fictive heir to Pericles, who supposedly had convened a previous Panhellenic Congress – such a Congress is mentioned only in Pericles' biography by Plutarch, whose sympathies to the Imperial order are well-known.[198] Epigraphical evidence suggests that the prospect of "applying" to the Panhellenion raised less interest in the wealthier cities of Asia Minor, which were jealous of Athenian and European Greek preeminence.[199] Hadrian defined Hellenism in a narrow, archaising way. No Hellenistic foundations were admitted into the Panhellenion, as Hadrian defined "Greekness" in terms of classical roots alone.[200] The fact was that the old world of civic honours was long dead, something admitted even by Hadrian in a later (134) letter to the city of Alexandria Troas deciding that payment of local prizes and allowances to winners of athletic games should begin after the announcement of the victory, and not (as had been decided earlier by Trajan) upon the athlete's return to his hometown – proof that athletes had become professional and could not afford to break their "international" touring to receive a prize.[201]

From Greece, Hadrian proceeded by way of Asia to Egypt. It is known from an inscription that he was probably conveyed across the Aegean with his entourage by one Ephesian, Lucius Erastus. Hadrian later sent a letter on Erastus' behalf to the Council of Ephesus, stating that he wanted to become a town councillor. Hadrian stated that he was willing to pay the honorary sum required for Erastus' entrance in the council, if the Ephesians regarded Erastus (who, as a merchant, was probably snubbed upon as unfit for civic prominence) worthy to fill such a position.[202]

In Egypt, Hadrian opened his stay by restoring Pompey the Great's tomb at Pelusium.[203] Hadrian also offered sacrifice to Pompey as a hero and composed an epigram for the tomb. As Pompey was universally acknowledged as the conqueror of the Roman East, this restoration was probably linked to a need to reaffirm Roman Eastern hegemony after the recent disturbances there during Trajan's late reign.[204] Also in Egypt, a poem about a lion hunt in the Libyan desert by the Greek Pankrates witnesses for the first time that Antinous travelled alongside Hadrian.[205]

In October 130, while Hadrian and his entourage were sailing on the Nile, Antinous drowned. The exact circumstances surrounding his death are unknown, and accident, suicide, murder and religious sacrifice have all been postulated. Historia Augusta offers the following account:

During a journey on the Nile he lost Antinous, his favourite, and for this youth he wept like a woman. Concerning this incident there are varying rumours; for some claim that he had devoted himself to death for Hadrian, and others – what both his beauty and Hadrian's sensuality suggest. But however this may be, the Greeks deified him at Hadrian's request, and declared that oracles were given through his agency, but these, it is commonly asserted, were composed by Hadrian himself.[206]

It was at that time that Hadrian turned, by his personal initiative, the persona of Antinous – a low-status non-citizen Greek – into something far surpassing the usual imperial boy favourite and sexual interest.[207] Deeply saddened, Hadrian founded the Egyptian city of Antinopolis in his memory, and had Antinous deified – an unprecedented honour for one not of the ruling family.

Although Hadrian was criticized for the intensity of his grief over Antinous's death, his attempt at turning the deceased youth into a cult-figure found little opposition.[208] The cult of Antinous was to become very popular in the Greek-speaking world.[209] It has been suggested that Hadrian created the cult as a political move to reconcile the Greek-speaking East to Roman rule.[210] The existence of a copy, in Hadrian's villa, of the famous statue pair of the Tyrannicides, with a bearded Aristogeiton and a clean-shaven Harmodios, in a certain way linked the imperial favourite to the classical tradition of Greek love[211] in opposition to usual Roman distrust of Greek pederasty.[212] In Italy and the West, the cult also found supporters: in one inscription from Tivoli, Antinous was compared to the Celtic sun-god Belenos.[213]

Medals were struck with Antinous's effigy, and statues erected to him in all parts of the empire, in all kinds of garb, including Egyptian dress.[214] Temples were built for his worship in Bithynia and Mantineia in Arcadia. In Athens, festivals were celebrated in his honour and oracles delivered in his name. The site chosen for the city of Antinopolis (or Antinoe) was on the ruins of Besa, in the vicinity of Antinous's death-place.[215] The city was a proper Greek polis, which besides benefitting from an alimentary scheme similar to Trajan's alimenta,[216] also allowed its citizens the privilege of marrying members of the native population without disenfranchising themselves – proof that Hadrian intended, again, to use a local religious cult (in this case, an Egyptianized one) to integrate native populations into the celebration of Roman rule.[217] Antinous's cult differed from the previous imperial cult in that, instead of centring on worshipping the Emperor as a ruler, it involved the Emperor as well as his subjects in a common religious activity, thereby emphasizing a sense of shared community.[218] Eventually, it was very successful. As an "international" cult figure, Antinous had an enduring fame, far outlasting Hadrian's reign.[219] Local coins with his effigy were still being struck during Caracalla's reign, and he was invoked in a poem to celebrate the accession of Diocletian.[220]

Greece and the East; return to Rome (130–133)

.jpg)

Hadrian's movements after the founding of Antinopolis on 30 October 130 are obscure. Whether or not he returned to Rome, he travelled in the East during 130/131 (see below) and spent the winter of 131–32 in Athens, where he dedicated the Olympeion,[221] and probably remained in Greece or went East because of the Jewish rebellion, which broke out in Judaea in 132 (see below). Inscriptions make it clear that he took to the field in person against the rebels with his army in 133. He then returned to Rome, probably in that year and almost certainly – again, judging from inscriptions – via Illyricum.[222] This third and last trip to the Greek East produced much religious enthusiasm in the region centred around Hadrian, who received a personal cult as a deity and many monuments and civic homages, according to the religious syncretism at the time.[223]

Legal reforms and State apparatus

It was around that time that Hadrian enacted, through the jurist Salvius Julianus, what was to become the first attempt to codify Roman law. This was the Perpetual Edict, according to which the various forms of legal action introduced yearly by praetors were to remain fixed.[224] The practical meaning of this measure was that a law could no longer be changed by a magistrate's personal interpretation of it; it was a fixed statute, which only the Emperor could alter.[225] At the same time, following a procedure initiated by Domitian, Hadrian professionalised the Emperor's legal advisory board, the Prince's Counsel or consilia principis, which became a permanent body staffed by salaried legal aides.[226] By so doing, Hadrian developed a professional bureaucracy, consisting mainly of equestrians, replacing the earlier freedmen of the Imperial household,[227] that was to control the political field instead of the Senate's members.[228] This innovation marked the superseding of surviving Republican institutions by an openly autocratic political system.[229] Hadrian's bureaucracy was supposed to carry out the administrative functions not exercised earlier by the old magistrates, and objectively it did not detract from the Senate's position. The new civil servants were free men and as such supposed to act on behalf of the interests of the "Crown", not of the Emperor as an individual.[227] However, the Senate never accepted the loss of its prestige caused by the emergence of a new aristocracy alongside it, placing more strain on the already troubled relationship between the Senate and the Emperor that was to be a hallmark of the end of Hadrian's reign.[230]

Hadrian and Judea; Second Roman–Jewish War and Jewish persecution (132–136)

In 130/131, Hadrian toured the East, bestowing honorific titles on many regional centres.[231] Palmyra received a state visit and was given the civic name Hadriana Palmyra.[232] Hadrian also bestowed honours on various Palmyrene magnates, among them one Soados, who lived in the Parthian city of Vologesias and, as a go-between had done much to protect Palmyrene trade between the Roman Empire and Parthia.[233]

Hadrian visited the ruins of Jerusalem, in Roman Judaea, left after the First Roman–Jewish War of 66–73. According to a midrashic tradition, he first showed himself sympathetic to the Jews, allegedly planning to have the city rebuilt and allowing the rebuilding of the Temple,[234] but when told by Samaritans that it would be the catalyst for sedition, he changed his mind.[235] The reliability of this tradition is doubtful.[236] The account stands in sharp contradiction to an alternate tradition that has Hadrian deciding to build a temple to the Roman god Jupiter on the ruins of the Temple Mount[237] and other temples to various Roman gods throughout Jerusalem, including a large temple to the goddess Venus.[238]

According to modern scholar Giovanni Bazzana, Hadrian's original intention may have been to rebuild Jerusalem as a Roman colony – such as Vespasian had done earlier to Caesarea Maritima – with various honorific and fiscal privileges, as well as a pagan population. It is accepted that the usual Roman policy in other colonies involved exempting the Jewish population from participating in Roman religious rituals. What was demanded from Jewish communities was political support of the Roman imperial order, as attested in Caesarea, where epigraphy attests that some of its Jewish citizens served in the Roman army during both the 66 and 132 rebellions.[239]

It has been speculated that Hadrian intended to assimilate the Jewish Temple into the civic-religious basis of support to his reign, as he had done with Greek and other traditional places of worship.[240] It has also been ventured that Hadrian attempted to unify all belief systems in his empire as a coherent whole that would serve as a basis of support for his autocratic legitimacy – a project that had already been devised earlier by Hellenized Jewish intellectuals such as Philo.[241] The neighbouring Samaritans had already undergone such a process of Hellenisation and religious syncretism, integrating their religious rites with Hellenistic ones.[242] Hadrian probably sanctioned this Hellenised Samaritan worship when, after the suppression of the Jewish revolt, he built a temple to the Hellenistic (and probably syncretic) god Zeus Hypsistos ("Highest")[243] on Mount Gerizim.[244] This attempt at conciliation between Judaism and Hellenism foundered when faced with strict Jewish monotheism.[245] Therefore, the Romans appear to have been surprised by the outbreak of the uprising.[246]

The evidence for this failure to integrate Judaism into a unified religious system lies in the fact that, after the war, Hadrian even renamed Jerusalem itself, as Aelia Capitolina after himself and Jupiter Capitolinus, the chief Roman deity. According to Epiphanius, Hadrian appointed Aquila from Sinope in Pontus as "overseer of the work of building the city", since he was related to him by marriage.[247] Hadrian is said to have placed the city's main Forum at the junction of the main Cardo and Decumanus Maximus, now the location for the (smaller) Muristan.

A tradition based on the Historia Augusta suggests that tensions grew higher when Hadrian abolished circumcision (brit milah),[248] which as a Hellenist he viewed as mutilation.[249] The scholar Peter Schäfer maintains that there is no evidence for this claim, given the notoriously problematical nature of the Historia Augusta as a source, the "tomfoolery" shown by the writer in this particular relevant passage, and the fact that contemporary Roman legislation on "genital mutilation" seems to address the general issue of castration of slaves by their masters.[250][251][252] Actually, Hadrian had issued a rescript with a blanket ban on castration, performed on freeman or slave, voluntarily or not, on pain of death for both the performer and the patient.[253] Castration was legally put by Hadrian on a par with conspiracy to murder and accordingly punished on the terms of the Lex Cornelia de Sicaris et Veneficis.[254]

The notion of an "antisemitic" legislation by Hadrian is, therefore, possibly an anachronistic ("midrashic", in the words of a modern scholar)[255] reading of ancient sources.

It is possible that other issues intervened between Hadrian's intention to rebuild Jerusalem and the outbreak of the war. The tension between incoming Roman colonists and supporters who had appropriated land confiscated after the First Jewish War and the landless poor, as well as the existence of messianic groups triggered by an interpretation of Jeremiah's prophecy promising that the Temple would be rebuilt seventy years after its destruction, repeating the timing of the restoration of the First Temple after the Babylonian exile – something that would put the restoration of the Second Temple to around 140.[256]

Hadrian's anti-Jewish policies (or, alternatively, assimilation policies by means of cultural and political hellenisation)[257] triggered a massive anti-Hellenistic and anti-Roman Jewish uprising in Judea, led by Simon bar Kokhba. Based on the delineation of years in Eusebius' Chronicon (now Chronicle of Jerome), it was only in the 16th year of Hadrian's reign, or what was equivalent to the 4th year of the 227th Olympiad, that the Jewish revolt began, under the Roman governor Tineius (Tynius) Rufus who had asked for an army to crush the resistance. Bar Kokhba, the leader of the resistance, punished any Jew who refused to join his ranks.[258] According to Justin Martyr and Eusebius, that had to do mostly with Christian converts, who opposed bar Kokhba's messianic claims.[259]

It was then that Hadrian called his general Sextus Julius Severus from Britain, and troops were brought from as far as the Danube. The Fifth Macedonian Legion and the Eleventh Claudian Legion also took part in war operations in Judea at the time.[260] Roman losses were very heavy – as they were compared by Fronto to the casualties of the earlier British uprising[261][262] – and it is believed that an entire legion, the XXII Deiotariana, which according to epigraphy did not outlast Hadrian's reign, was destroyed in the rebellion.[263] Indeed, Roman losses were so heavy that Hadrian's report to the Roman Senate omitted the customary salutation, "If you and your children are in health, it is well; I and the legions are in health."[264]

Hadrian's army eventually put down the rebellion in 135. According to Cassius Dio, overall war operations in the land of Judea left some 580,000 Jews killed, and 50 fortified towns and 985 villages razed to the ground. The most famous battle took place in Beitar, a fortified city 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) southwest of Jerusalem. The city only fell after a lengthy siege of three and a half years, at which time Hadrian prohibited the Jews from burying their dead. They were eventually afforded burial when Antoninus Pius succeeded Hadrian as Roman Emperor.[265] According to the Babylonian Talmud,[266] after the war Hadrian continued the persecution of Jews.

The rabbinical sources, however, seem more concerned with morals and religion than with conveying history.[267] Such writings are known occasionally to contain embellished accounts of the war and its aftermath,[268] claiming that Hadrian attempted to root out Judaism – which he saw as the cause of continuous rebellions – prohibited the Torah law, the Hebrew calendar and executed Judaic scholars (see Ten Martyrs). The sacred scroll was ceremonially burned on the Temple Mount. In an attempt to erase the memory of Judea, he renamed the province Syria Palaestina (after the Philistines; the name was found in Herodotus' histories),[269] and Jews were barred from entering its rededicated capital. When Jewish sources mention Hadrian it is always with the epitaph "may his bones be crushed" (שחיק עצמות or שחיק טמיא, the Aramaic equivalent[270]), an expression never used even with respect to Vespasian or Titus, who destroyed the Second Temple.

Other modern scholars contend that Hadrian's strictures on circumcision, and his no-entry policy for Jews were poorly enforced, falling into abeyance with his death. Namely, Hadrian's legislation on castration was amended by Antoninus Pius of to allow Jews to circumcise their own sons (Jewish proselytism among male converts remaining forbidden).[271] In spite of the enslavement of Jewish war prisoners, and of their suffering high war casualties and wanton destruction, it has been proposed that Palestine remained predominantly Jewish in population, as well as its culture and religious life, a fact reflected by the completion of the Mishnah in the early Third Century (220 CE).[272] However, the Jerusalem Talmud, compiled in the 2nd and 3rd century CE, speaks of areas in Palestine that were at that time wholly supplanted by non-Jewish peoples, owing to the sparseness of its Jewish citizens.[273] Jerusalem remained a special case, since it was rebuilt as a purely Roman city – a circumstance of which later Christian authors like Eusebius took advantage to stress its character as a Christian city and worship centre.[274] Therefore, the extent of the punitive measures taken by Hadrian against the Jewish population remains a matter of continuing debate in present-day historiography.[275]

What Hadrian's bloody repression of the revolt undoubtedly did accomplish was to put an end to any measure of Jewish political independence alongside the Roman Imperial order.[276]

In Rabbinic literature

Rabbinic literature is critical of Hadrian's policy, particularly that of religious intolerance concerning the Jews. Indeed, his policies were viewed as an attack on the religious freedom of the practice of Torah law. Most of the stories related by the Chazal (Sages of Israel) reflect a two-faced approach to tolerance of the Jewish people. In one story, he punishes a Jew who failed to greet him, and then punishes another Jew who wished him well. When asked what the logic was for his punishing both men, he replied: "You wish to give me advice on how to kill my enemies?"[277]

In another story, Hadrian got down from his chariot and bowed to a Jewish girl afflicted with leprosy. When queried by his soldiers as to why he did this, Hadrian responded with a dual verse from the book of Isaiah in praise of the nation of Israel: "So says God the redeemer of Israel to the downtrodden soul to the (made) repulsive nation, kings will view and stand."[278]

The Malbim commentary to the book of Daniel comments how Hadrian erected a statue of himself at the site of the Bet HaMikdash on a day marking the anniversary of the Temple's destruction by Titus.[279]

According to Jewish historical records of that time,[280] the famous rabbi and scholar and a contemporary of Hadrian, Rabbi Yehoshua, the son of Hananiah, opposed any Jewish military intervention against the occupying Roman army, in spite of Rome's harsh decrees against the Jewish people. Rabbi Yehoshua is reported as saying: "A lion once pounced upon its prey and got a bone stuck in his throat. He then said, 'Whosoever comes and takes it out, I will give to him a reward.' An Egyptian heron came along whose bill is long, and reaching down into the lion's throat, extracted the bone. The bird then said to the lion, 'Give to me my reward.' The lion replied, 'Just be happy that you can say, I went down into the lion's mouth and I came out alive and well.' It is the same with us. It is enough that we have gone into this nation and came out with our lives."

Final years

Succession

Hadrian spent the final years of his life at Rome. In 134, he took an Imperial salutation for the end of the Second Jewish War (which was not actually concluded until the following year). Commemorations and achievement awards were kept to a minimum, as Hadrian came to see the war "as a cruel and sudden disappointment to his aspirations" towards a cosmopolitan empire.[281] In 136, he dedicated a new Temple of Venus and Roma on the former site of Nero's Golden House. The temple was built in an Hellenising style, more Greek than Roman, and its double nature associated the worship of the traditional Roman goddess Venus with the worship of Roma – a goddess until then worshiped only in the provinces – in order to stress the universal nature of the empire.[282]