Hadley cell

The Hadley cell, named after George Hadley, is a global scale tropical atmospheric circulation that features air rising near the equator, flowing poleward at 10–15 kilometers above the surface, descending in the subtropics, and then returning equatorward near the surface. This circulation creates the trade winds, tropical rain-belts and hurricanes, subtropical deserts and the jet streams.

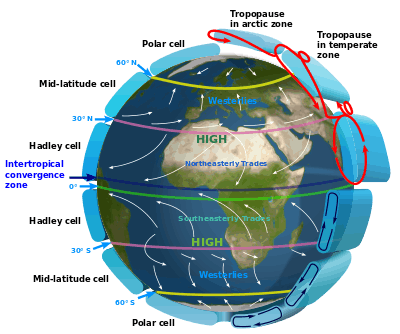

In each hemisphere, there is one primary circulation cell known as a Hadley cell and two secondary circulation cells at higher latitudes, between 30° and 60° latitude known as the Ferrel cell, and beyond 60° as the Polar cell. Each Hadley cell operates between zero and 30 to 40 degrees north and south and is mainly responsible for the weather in the equatorial regions of the world.

Mechanism

The major driving force of atmospheric circulation is the uneven distribution of solar heating across the Earth, which is greatest near the equator and lesser at the poles. The atmospheric circulation transports energy polewards, thus reducing the resulting equator-to-pole temperature gradient. The mechanisms by which this is accomplished differ in tropical and extratropical latitudes.

Hadley cells exist on either side of the equator. Each cell encircles the globe latitudinally and acts to transport energy from the equator to about the 30th latitude. The circulation exhibits the following phenomena[1]:

- Warm, moist air converging near the equator causes heavy precipitation. This releases latent heat, driving strong rising motions.

- This air rises to the tropopause, about 10-15 kilometers above sea level, where the air is no longer buoyant.

- Unable to continue rising, this sub-stratospheric air is instead forced poleward by the continual rise of air below.

- As air moves poleward, it both cools and gains a strong eastward component due to the Coriolis effect and the conservation of angular momentum. The resulting winds form the subtropical jet streams.

- At about 30º latitude on either side of the equator, the jet streams become so much faster than the surface wind speed that baroclinic instability prevents the Hadley circulation from extending further poleward. This coincides with the beginning of the Ferrel cells.

- At this latitude, the now cool, dry, high altitude air begins to sink. As it sinks, it warms adiabatically, decreasing its relative humidity.

- Near the surface, a frictional return flow completes the loop, absorbing moisture along the way. The Coriolis effect gives this flow a westward component, creating the trade winds.

The Hadley circulation exhibits seasonal variation. During the solstitial seasons (DJF and JJA), the upward branch of the Hadley cell occurs not directly over the equator but rather in the summer hemisphere. In the annual mean, the upward branch is slightly offset into the northern hemisphere, making way for a stronger Hadley cell in the southern hemisphere. This evidences a small net energy transport from the northern to the southern hemisphere.[1]

The Hadley system provides an example of a thermally direct circulation. The thermodynamic efficiency of the Hadley system, considered as a heat engine, has been relatively constant over the 1979~2010 period, averaging 2.6%. Over the same interval, the power generated by the Hadley regime has risen at an average rate of about 0.54 TW per yr; this reflects an increase in energy input to the system consistent with the observed increasing of tropical sea surface temperatures.[2]

Overall, mean meridional circulation cells such as the Hadley circulation are not particularly efficient at reducing the equator-to-pole temperature gradient due to cancellation between transports of different types of energy. In the Hadley cell, both sensible and latent heat are transported equatorward near the surface, while potential energy is transported above in the opposite direction, poleward. The resulting net poleward transport is only about 10% of this potential energy transport. This is partly a result of the strong constraints imposed on atmospheric motions by the conservation of angular momentum.[1]

History of discovery

In the early 18th century, George Hadley, an English lawyer and amateur meteorologist, was dissatisfied with the theory that the astronomer Edmond Halley had proposed for explaining the trade winds. What was no doubt correct in Halley's theory was that solar heating creates upward motion of equatorial air, and air mass from neighboring latitudes must flow in to replace the risen air mass. But for the westward component of the trade winds Halley had proposed that in moving across the sky the Sun heats the air mass differently over the course of the day. Hadley was not satisfied with that part of Halley's theory and rightly so. Hadley was the first to recognize that Earth's rotation plays a role in the direction taken by an air mass as it moves relative to the Earth. Hadley's theory, published in 1735, remained unknown, but it was rediscovered independently several times. Among the re-discoverers was John Dalton, who later learned of Hadley's priority. Over time the mechanism proposed by Hadley became accepted, and over time his name was increasingly attached to it. By the end of the 19th century it was shown that Hadley's theory was deficient in several respects. One of the first who accounted for the dynamics correctly was William Ferrel. It took many decades for the correct theory to become accepted, and even today Hadley's theory can still be encountered occasionally, particularly in popular books and websites.[3] Hadley's theory was the generally accepted theory long enough to make his name become universally attached to the circulation pattern in the tropical atmosphere. In 1980 Isaac Held and Arthur Hou developed the Held-Hou Model to describe the Hadley circulation.

Major impacts on precipitation by latitude

The region in which the equatorward moving air masses converge and rise, is known as the intertropical convergence zone, or ITCZ. Within that zone develops a band of thunderstorms that produce high-precipitation.

Having lost most of its water vapor to condensation and precipitation in the upward branch of the Hadley cell circulation, the descending air is dry. As the air descends, low relative humidities are produced as the air is warmed adiabatically by compression from the overlying air, producing a region of higher pressure. The subtropics are relatively free of the convection, or thunderstorms, that are common in the equatorial belt. Many of the world's deserts are located in these subtropical latitudes.

Hadley cell expansion

There is some evidence that the expansion of the Hadley cells is related to climate change.[4] The majority of Earth's arid regions are located in the areas beneath the descending part of the Hadley circulation at around 30 degrees latitude.[5] Those models show that the Hadley cell will expand with increased global mean temperature (perhaps by 2 degrees latitude over the 21st century [6]). This might lead to large changes in precipitation in the latitudes at the edge of the cells.[5] Scientists fear that global warming might bring changes to the ecosystems in the deep tropics and that the deserts will become drier and expand.[6] As the areas around 30 degrees latitude become drier, those inhabiting that region will see less rainfall than traditionally expected, which could cause difficulty with food supplies and livability.[7] There is strong evidence of paleoclimate climate change in central Africa's rain forest in c. 850 B.C.[8] Palynological (fossil pollen) evidence shows a drastic change in rain forest biome to that of open savannah as a consequence of wide-scale drying not connected necessarily to intermittent drought but perhaps to gradual warming. The hypothesis, that a decline in solar activity reduces the latitudinal extent of the Hadley Circulation and decreases mid-latitudinal monsoon intensity, is matched by data, showing increased dryness in central west Africa and increase in precipitation in temperate zones north. Meanwhile, mid-latitudinal storm tracks in the temperate zones increased and moved equatorward.[9]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 L.,, Hartmann, Dennis. Global physical climatology. Elsevier. pp. 165–76. ISBN 9780123285317. OCLC 944522711.

- ↑ Junling Huang; Michael B. McElroy (2014). "Contributions of the Hadley and Ferrel Circulations to the Energetics of the Atmosphere over the Past 32 Years". Journal of Climate. 27 (7): 2656–2666. Bibcode:2014JCli...27.2656H. doi:10.1175/jcli-d-13-00538.1.

- ↑ Anders Persson (2006). "Hadley's Principle: Understanding and Misunderstanding the Trade Winds" (PDF). History of Meteorology. 3: 17–42.

- ↑ Xiao-Wei Quan; Henry F. Diaz; Martin P. Hoerling (2004). "Changes in the Tropical Hadley Cell since 1950". In Henry F. Diaz; Raymond S. Bradley. The Hadley Circulation: Present, Past, and Future. Advances in Global Change Research. 21. Springer Netherlands. pp. 85–120. ISBN 978-1-4020-2943-1. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-2944-8. Preprint at 'Change of the Tropical Hadley Cell Since 1950', NOAA-CIRES Climate Diagnostic Center (2004) (PDF file 2.9 MB)

- 1 2 Dargan M.W. Frierson; Jian Lu; Gang Chen (2007). "Width of the Hadley cell in simple and comprehensive general circulation models" (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters. 34 (18): L18804. Bibcode:2007GeoRL..3418804F. doi:10.1029/2007GL031115.

- 1 2 Dian J. Seidel; Qian Fu; William J. Randel; Thomas J. Reichler (2007). "Widening of the tropical belt in a changing climate". Nature Geoscience. 1 (1): 21–4. Bibcode:2008NatGe...1...21S. doi:10.1038/ngeo.2007.38.

- ↑ Celeste M. Johanson; Qiang Fu (2009). "Hadley Cell Widening: Model Simulations versus Observations" (PDF). Journal of Climate. 22 (10): 2713–25. Bibcode:2009JCli...22.2713J. doi:10.1175/2008JCLI2620.1.

- ↑ van Geel B.,van der Plicht, J.,Kilian, M.R., (1998). "The sharp rise of 14C ca. 800 cal BP:possible causes, related climatic teleconnections and the impact on human environments.". Radiocarbon. 40 (1): 535–550.

- ↑ van Geel B., Renssen, H., (1998). "Abrupt climate change around 2650 BP in North-West Europe:evidence for climatic teleconnections and a tentative explanation". In Issar, A.S.,Brown, N. Water, Environment and Society in Times of Climatic Change. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht. pp. 21–41.

External links

- Planetary-scale tropospheric systems, John Brandon's 'Fly Safe!' tutorials

- Planetary scale tropospheric systems, Recreational Aviation Australia