Hachijō-jima

| Native name: 八丈島 Nickname: Hachijō Island | |

|---|---|

Hachijō-fuji | |

| |

| Geography | |

| Location | Izu Islands |

| Coordinates | 33°06′34″N 139°47′29″E / 33.10944°N 139.79139°E |

| Archipelago | Izu Islands |

| Area | 62.52 km2 (24.14 sq mi) |

| Length | 14 km (8.7 mi) |

| Width | 7.5 km (4.66 mi) |

| Coastline | 58.91 km (36.605 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 854.3 m (2,802.8 ft) |

| Administration | |

|

Japan | |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 8363 (September 2009) |

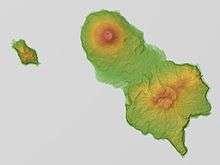

Hachijō-jima (八丈島) is a volcanic Japanese island in the Philippine Sea.[1] The island is administered by Tōkyō and located approximately 287 kilometres (178 mi) south of the Special Wards of Tōkyō. It is the southernmost and most isolated of the Izu Seven Islands group of the seven northern islands of the Izu archipelago. The chief community on the island is Mitsune; other communities are Nakanogo, Kashitate, and Ōkago all of which are administratively part of the town of Hachijō under Hachijō Subprefecture of Tokyo Metropolis. As of 2009, the island's population was 8,363 people living on 63 km2. The highest elevation is about 850 metres (2,790 feet). Hachijō-jima is also within the boundaries of the Fuji-Hakone-Izu National Park.

Geology

Hachijō-jima is a compound volcanic island 14.5 kilometres (9 miles) in length with a maximum width of 8 kilometres (5 miles). The island is formed from two stratovolcanoes.[2] Higashi-yama (東山), also called Mihara-yama (三原山), has a height of 701 metres (2,300 ft), and was active from 100,000 BC to around 1700 BC, has eroded flanks and retains a distinctive caldera. Nishi-yama (西山), also called Hachijō-fuji (八丈富士) is the highest point on the island and is the tallest peak of the entire Izu island chain, with a height of 854 metres (2,802 ft). The summit is occupied by a shallow caldera with a diameter of 400 metres (1,300 feet) and a depth of around 50 metres (160 feet). It is rated as a Class-C active volcano by the Japan Meteorological Agency with eruptions recorded in recent history in 1487, 1518, 1522–1523, 1605 and 1606. In between these two peaks are over 20 flank volcanoes and pyroclastic cones.

History

Hachijō-jima has been inhabited since at least the Jōmon period, and archaeologists have found magatama and other remains.[3] Under the Ritsuryō system of the early Nara period, the island was part of Suruga Province. It was transferred to Izu Province when Izu separated from Suruga in 680. During the Heian period, Minamoto no Tametomo was banished to Izu Ōshima after a failed rebellion, but per a semi-legendary story, escaped to Hachijō-jima, where he attempted to establish an independent kingdom.[4]

During the Edo period, the island became known as a place of exile for convicts, most notably Ukita Hideie,[5] a daimyō who was defeated at the Battle of Sekigahara. Originally the island was a place of exile mainly for political figures, but beginning in 1704 the criteria for banishment were broadened. Crimes punishable by banishment included murder, theft, arson, brawling, gambling, fraud, jailbreak, rape, and membership of an outlawed religious group. Criminals exiled to the island were never informed as to the length of their sentences, and the history of the island is filled with foiled escape attempts. Its use as a prison island ended during the Meiji Restoration, after a general amnesty in 1868 most of the island's residents chose to move to the mainland, however the policy of banishment was not officially abolished until 1881.[6]

The island was visited by former U.S. president Ulysses S. Grant during his 1877 world tour. He was given a jubilant welcome by the island's residents, who were aware of his exploits in the American Civil War. Ulysses was ceremonially adopted by the village chief, being given the name Yūtarotaishō; meaning 'courageous general' in the local dialect, and was presented with prayer beads made with pearls and gemstones. He declared that the island's residents were the "friendliest people in the pacific".[7]

In 1900, pioneers from Hachijō became the first inhabitants of the Daitō Islands, where they established a sugarcane farming industry. The Hachijō language is still spoken on the islands to this day.[8]

During the Pacific War, the island was regarded as a strategic point in the defense of the ocean approaches to Tokyo, and in the final stages of the war, a base of operations for the Kaiten suicide submarines was founded on the southern coast.[9] Following the end of World War II through the 1960s, the government made attempts to promote Hachijōjima as the "Hawaii of Japan" to encourage tourist development,[10] and tourism remains a large component of the island's economy to date.

Language

The Hachijō language is the most divergent form of Japanese; it is the only surviving descendant of Eastern Old Japanese.[11] The number of speakers is not certain; it is on the list of endangered languages,[12] and is likely to be extinct by 2050 if counter-measures are not taken.[13]

Climate

Hachijō-jima has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa) with very warm summers and mild winters. Precipitation is abundant throughout the year, but is somewhat lower in winter.

| Climate data for Hachijō-jima | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 12.9 (55.2) |

13.1 (55.6) |

15.3 (59.5) |

19.2 (66.6) |

22.0 (71.6) |

24.4 (75.9) |

27.6 (81.7) |

29.2 (84.6) |

27.5 (81.5) |

23.5 (74.3) |

19.9 (67.8) |

15.6 (60.1) |

20.85 (69.53) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 10.2 (50.4) |

10.2 (50.4) |

12.2 (54) |

16.2 (61.2) |

19.2 (66.6) |

22.0 (71.6) |

25.1 (77.2) |

26.4 (79.5) |

24.8 (76.6) |

20.7 (69.3) |

17.1 (62.8) |

12.8 (55) |

18.08 (64.55) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 7.5 (45.5) |

7.5 (45.5) |

9.4 (48.9) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.5 (61.7) |

19.8 (67.6) |

23.2 (73.8) |

24.2 (75.6) |

22.5 (72.5) |

18.2 (64.8) |

14.4 (57.9) |

10.0 (50) |

15.55 (59.99) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 175.2 (6.898) |

179.7 (7.075) |

257.6 (10.142) |

238.8 (9.402) |

249.2 (9.811) |

350.3 (13.791) |

189.2 (7.449) |

204.0 (8.031) |

344.1 (13.547) |

456.8 (17.984) |

255.2 (10.047) |

173.3 (6.823) |

3,073.4 (121) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 65 | 67 | 70 | 75 | 80 | 87 | 88 | 85 | 82 | 76 | 72 | 67 | 76.2 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 94.8 | 90.9 | 125.5 | 142.2 | 152.7 | 106.2 | 150.3 | 199.2 | 148.2 | 121.2 | 105.5 | 103.1 | 1,539.8 |

| Source: NOAA (1961–1990) [14] | |||||||||||||

Transportation

Hachijō-jima is accessible both by aircraft and by ferry. A pedestrian ferry leaves Tōkyō once every day at 10:30 p.m., and arrives at Hachijōjima at 8:50 a.m. the following day. Air travel to Hachijojima Airport takes 45 minutes from Tōkyō International Airport (Haneda).[15]

Notable landmarks

The island is home to the Hachijo Royal Resort, a now-abandoned French Baroque-style luxury hotel that was built during the tourism boom of the 1960s. When the hotel was built in 1963 it was one of the largest in Japan, and attracted visitors from all over the country. The hotel was finally closed in 2006 due to declining tourism to the island. As of March 2017, the grounds are overgrown and the building is severely dilapidated.[10]

Activities and accommodation

Accommodation on Hachijō-jima is plentiful. There are many Japanese-style inns, hot spring resorts and several larger hotels. There is also a free campsite that is open year-round; reservations are not required. The campsite has numerous BBQ pits, cold showers and full cooking facilities.[16]

Hachijō-jima is popular with surfers, with three reef breaks and consistently warmer water than mainland Japan because of the warm water Kuroshio Current.[6] Due to the fact that Hachijō-jima is a volcanic island there are a few black sandy beaches, the main one is next to the main harbour of Sokodo. Hachijō-jima's scuba diving points are many and varied. Nazumado is the best known, and is considered one of the top 5 diving spots in Japan.[17] Sea turtles are common and underwater lava bridges are typical features for a volcanic island. Hachijōjima is also known for its hiking, waterfalls, and natural beauty. Other activities for visitors include visiting the botanical gardens, exploring wartime tunnels and hiking to the top of Hachijō-fuji.[18]

Kihachijō silk cloth is woven on the island, and one of the workshops is open to tourists.[18] The Tokyo Electric Power Company operates a free museum at its geothermal power plant.[19]

Flora and fauna

Since November 2015, humpback whales have been observed gathering around the island, far north from their known breeding areas in the Bonin Islands. All breeding activities except for giving births have been confirmed, and ongoing research is underway by the town of Hachijo-jima and the Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology to determine whether Hachijo-jima may become the northernmost breeding ground in the world, and possible expectations for opening a future tourism attraction.[20] Whales can be viewed even from hot springs.[21] Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins, likely (re)colonized from Mikura-jima, also live around the island[22] among with other cetaceans such as false killer whales,[23] sperm whales,[24] and orcas (being sighted during humpback whale research in 2017).[25]

The island is home to bioluminescent mushrooms known as Mycena Lux-Coeli meaning 'heavenly light mushrooms'. The fungi are widely found and for decades were believed only to exist on the island. The local name for the mushrooms is hato-no-hi; translated as 'pigeon fire'.[26]

Food

Hachijō-jima is famous for its sushi; known locally as shimazushi, and kusaya.[27] Local cuisine also makes use of the ashitaba plant in dishes such as ashitaba soba and tempura.[15]

Education

The town operates its public elementary and junior high schools.

Tōkyō Metropolitan Government Board of Education operates Hachijō High School.[28]

Gallery

Mt Hachijō-Fuji and Hachijō-Koshima island seen from the Noboryō Pass

Mt Hachijō-Fuji and Hachijō-Koshima island seen from the Noboryō Pass Tamaishigaki: walls built by convicts exiled on Hachijō-jima in the Edo Period

Tamaishigaki: walls built by convicts exiled on Hachijō-jima in the Edo Period The Karataki waterfall, in the hills around Mt. Mihara

The Karataki waterfall, in the hills around Mt. Mihara

Freesia Festival

Freesia Festival Aloe growing on Mt. Hachijō-Fuji

Aloe growing on Mt. Hachijō-Fuji Landsat image: Hachijō-jima and Hachijō-Koshima

Landsat image: Hachijō-jima and Hachijō-Koshima- Hachijō-jima view

- View from the top of the rock at Kurosuna, Hachijō

See also

- Runin: Banished, a 2004 film about convicts exiled to Hachijōjima and their attempts to escape

- Battle Royale, a controversial 2000 film filmed on the neighbouring, uninhabited, Hachijō Kojima, although not set on the island

- List of islands of Japan

Notes

- ↑ Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005). "Izu Shotō," Japan Encyclopedia, p. 412; Ponsonby-Fane, Richard. (1962). Sovereign and Subject, p. 332.

- ↑ https://www.volcanodiscovery.com/hachijo-jima.html

- ↑ Naumann, Nelly (Dec 31, 2000). Japanese Prehistory: The Material and Spiritual Culture of the Jōmon Period. p. 54. ISBN 978-3-447-04329-8.

- ↑ Onuma, Hideharu; DeProspero, Dan and Jackie (Jul 15, 1993). Kyudo: The Essence and Practice of Japanese Archery. p. 14. ISBN 978-4-7700-1734-5.

- ↑ Murdoch, James; Yamagata, Isoh (1903). A History of Japan. p. 432. ISBN 978-0-415-15076-7.

- 1 2 "Getting to Know Hachijo". Japanzine. Japan: Carter Witt Media. Jun 5, 2007. Retrieved Apr 13, 2017.

- ↑ Smith, Jean Edward (Apr 5, 2001). Grant. p. 588. ISBN 0-684-84926-7.

- ↑ Hayward, Philip; Long, Daniel (2013). "Language, music and cultural consolidation on Minami Daito". Perfect Beat. ISSN 1836-0343.

- ↑ Hastings, Max (Mar 18, 2008). Retribution:The Battle for Japan, 1944–45. p. 441. ISBN 978-0-307-27536-3.

- 1 2 Whitelocks, Sadie (Mar 17, 2017). "An empty bar and very soiled beds: The haunting carcass of Japan's most luxurious hotel after it was abandoned". Daily Mail. Retrieved Apr 13, 2017.

- ↑ Shibatani, Masayoshi (May 3, 1990). The Languages of Japan. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-521-36918-3.

- ↑ http://www.unesco.org/languages-atlas/en/atlasmap.html

- ↑ Heinrich, Patrick (Feb 10, 2012). The Making of Monolingual Japan: Language Ideology and Japanese Modernity. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-84769-659-5.

- ↑ "Hachijojima Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 5, 2013.

- 1 2 "Hachijo-jima - Floral Paradise". Hiragana Times. Japan. Feb 2010. Retrieved Apr 13, 2017.

- ↑ "Hachijojima: Island bliss not far from home". Tokyo Weekender. Jun 17, 2005. Retrieved Apr 13, 2017.

- ↑ Noorbakhsh, Sarah (Jul 3, 2008). "Tokyo's Secret Scuba". Japan Inc. Retrieved Apr 13, 2017.

- 1 2 http://www.japanvisitor.com/tokyo/hachijo

- ↑ http://www.geothermal-hachijo.com/brochure_e.pdf

- ↑ Hachijo Town. 2017. 八丈島ザトウクジラ調査について. Retrieved on March 13, 2017

- ↑ 2017. 八丈島に今年もザトウクジラがやってきた!

- ↑ Hachijo Visitor Center. ミナミハンドウイルカ. Retrieved on March 31, 2017

- ↑ 八丈島譲歩サイト BOOGEN. 2005. オキゴンドウと接近遭遇. Retrieved on March 31, 2017

- ↑ Ishida 光史. 2016. 国内の鳥(ツアー報告)-【ツアー報告】アホウドリに会いたい!東京~八丈島航路 2016年3月26日~27日. Naturing News.jp. Retrieved on March 31, 2017

- ↑ Hachijo-jima tourism organizations. 2017. 八丈島シャチ目撃情報 2017年2月9日 神湊東沖 on Youtube. Retrieved on March 31, 2017

- ↑ Bird, Winifred (Jun 11, 2008). "Luminescent mushrooms cast light on Japan's forest crisis". Japan Times. Retrieved Apr 13, 2017.

- ↑ Kendall, Philip (Sep 17, 2012). "Just 45 minutes from Haneda Airport: 6 things that make Hachijo-jima a hidden gem". Japan Today. Retrieved Apr 13, 2017.

- ↑ Homepage of Tokyo Toritsu Hachijoko School

References

- Teikoku's Complete Atlas of Japan, Teikoku-Shoin Co., Ltd. Tokyo 1990, ISBN 4-8071-0004-1

Further reading

- Tsune Sugimura; Shigeo Kasai, Hachijo: Isle of Exile, (Weatherhill 1973), ISBN 978-0-8348-0081-6

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hachijojima. |

- Hachijojima - Japan Meteorological Agency (in Japanese)

- "Hachijojima: National catalogue of the active volcanoes in Japan" (PDF). - Japan Meteorological Agency

- Hachijo Jima Volcano Group - Geological Survey of Japan

- Hachijojima: Global Volcanism Program - Smithsonian Institution