Habiru

Habiru or Apiru (Egyptian: ˁpr.w) was the name given by various Sumerian, Egyptian, Akkadian, Hittite, Mitanni, and Ugaritic sources (dated, roughly, between 1800 BC and 1100 BC) to a group of people living as nomadic invaders in areas of the Fertile Crescent from Northeastern Mesopotamia and Iran to the borders of Egypt in Canaan.[1] Depending on the source and epoch, these Habiru are variously described as nomadic or semi-nomadic, rebels, outlaws, raiders, mercenaries, and bowmen, servants, slaves, migrant laborers, etc. The Habiru are often identified as the early Hebrews.[2][3]

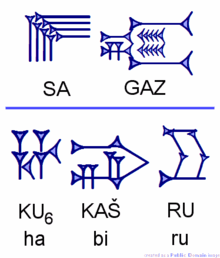

The names Habiru and Apiru are used in Akkadian cuneiform texts. The corresponding name in the Egyptian script appears to be ʕpr.w, conventionally pronounced Apiru (the w representing the Egyptian plural suffix). In Mesopotamian records they are also identified by the Sumerian logogram SA.GAZ. The name Habiru was also found in the Amarna letters to Egyptian pharaohs, along with many names of Canaanite peoples written in Akkadian.

Sources

As more texts were uncovered throughout the Near East, it became clear that the Habiru were mentioned in contexts ranging from unemployed agricultural laborers and vagrants to mounted mercenary bowmen. The context differed depending upon where the references were found.

Although found throughout most of the Fertile Crescent, the arc of civilization "extending from the Tigris-Euphrates river basins over to the Mediterranean littoral and down through the Nile Valley during the Second Millennium, the principal area of historical interest is in their engagement with Egypt."[4]

Carol Redmount, who authored "Bitter Lives: Israel in and out of Egypt" included The Oxford History of the Biblical World, concluded that the term "Habiru" had no common ethnic affiliations, that they spoke no common language, and that they normally led a marginal and sometimes lawless existence on the fringes of settled society.[5] She defines the various Apiru/Habiru as "a loosely defined, inferior social class composed of shifting and shifty population elements without secure ties to settled communities" who are referred to "as outlaws, mercenaries, and slaves" in ancient texts.[5] In that vein, some modern scholars consider the Habiru to be more of a social designation than an ethnic or a tribal one.[6]

Sumerian records

The earliest recorded instance of the term is dated to the reign of king Irkabtum of the north Syrian (Amorite) kingdom of Yamkhad (c. 1740 BC), who had a year named "Year when king Irkabtum made peace with Semuma and the Habiru." This has been taken to show that the Habiru led by Semuma already wielded such influence in the neighborhood of Alalakh that the local sovereign felt obliged to conclude a treaty with them.

Sumerian documents from the 15th century next describe these groups speaking various languages, and although described as vagrant, also having significant influence and military organisation. Those people are designated by a two-character cuneiform logogram transcribed as SA.GAZ, which is equated with the West Semitic hapiru and the Akkadian habbatu meaning bandit, robber or raider.[7]

Early Mesopotamian sources

The Sumerian logogram SA.GAZ appears in texts from Southern Mesopotamia, dated from about 1850 BC, where it is applied to small bands of soldiers, apparently mercenaries at the service of local city-states and being supplied with food or sheep.

One of those texts uses the Akkadian cuneiform word Hapiri instead of the logogram; another described them as "soldiers from the West". Their names are predominantly Akkadian; some are West Semitic, some unknown. Their origins, when recorded, are in local towns.

A letter to an Old Assyrian merchant resident in Alishar requests his aid in freeing or ransoming some Hapiri, formerly attached to the palace of Shalahshuwe (as yet unidentified), now prisoners of the local authorities.

The Tikunani Prism, dated from around 1550 BC, lists the names of 438 Habiru soldiers or servants of king Tunip-Teššup of Tikunani, a small city-state in central Mesopotamia. The majority of these names are typically Hurrian, the rest are Semitic, one is Kassite.

Another text from around 1500 BC describes the Hapiru as soldiers or laborers, organized into bands of various sizes commanded by SA.KAS leaders: one band from Tapduwa has 15 soldiers, another from Sarkuhe has 29, and another from Alalakh has 1,436. [8]

Meaning of SA.GAZ

SA.GAZ 'murderer, robber', literally 'one who smashes sinews', is an original Sumerian nominal compound attested as early as ca. 2500 BC. It is later equated with Akkadian habbātu 'plunderer, bandit' and šaggāšu 'murderer'. It has been suggested that a second Sumerian logogram SAG.GAZ 'one who smashes heads', a variant of SA.GAZ, may be artificially derived from the like-sounding šaggāšu, even though SAG.GAZ is attested in several unilingual Sumerian texts from at least 2100 BC. SA.GAZ and occasionally SAG.GAZ are equated with Akkadian hāpiru, a West Semitic loanword first attested in early 2nd millennium Assyrian and Babylonian texts, in texts from El Amarna in Egypt.[9]

Canaanite sources

A number of the Amarna letters—sent to pharaohs Amenhotep III, Akhenaten (Amenhotep IV) and, briefly, his two successors from vassal kings in Canaan and Syria in the 14th century BC — mention the "Habiru". These letters, written by Canaanite scribes in the cuneiform-based Akkadian language, complain about attacks by armed groups who were willing to fight and plunder on any side of the local wars in exchange for equipment, provisions, and quarters.

Those people are identified by the Sumerian logogram SA.GAZ in most of the letters, and by the Akkadian name Hapiru in a few from the area of Jerusalem. They appear to be active on a broad area including Syria (near Damascus), Phoenicia (Sumur, Batrun and Byblos), and to the south as far as Jerusalem. None of the kings of the region, with the possible exception of one Abdi-Ashirta, is called Habiru or SA.GAZ.

Sources also discuss one Labayu, who had been an Egyptian vassal, and set up for himself. Attacking Megiddo, he assembled a group of Hapiru who consisted of both dispossessed local people and invaders. Having won Megiddo for himself, he gave his supporters Shechem for their own (Harrelson, van der Steen).

Idrimi, the 15th century BC King of Alalakh, son of the King of Aleppo, states in his chronicles, that after his family had been forced to flee to Emar, with his mother's people, he left them and joined the "Hapiru people" in "Ammija in the land of Canaan", where the Hapiru recognized him as the "son of their overlord" and "gathered around him"; after living among them for seven years, he led his Habiru warriors in a successful attack by sea on Alalakh, where he became king.

Abdi-Heba, the Egyptian vassal ruler of Jerusalem in the Amarna period (mid-1330s BC), wrote a series of letters to the Egyptian king in which he complained about the activities of the "Habiru", who were plundering the king's lands.

Abdi-Heba wanted to know why the king was letting them behave in this way; why he was not sending archers to protect his, the king's properties. If he did not send military help the whole land would fall to the Habiru. [10]

Egyptian sources

| |||||

| ˁApiru (ʕprw)[11] in hieroglyphs |

|---|

Several Egyptian sources, both before and after the Amarna letters, mention a people called ʻPR.W in the consonant-only Egyptian script, where .W is the plural marker. The pronunciation of this word has been reconstructed as ˁapiru. From similarity of context and description, it is believed that the Egyptian ʻPR.W are equivalent to the Akkadian Habiru/Hapiru.

In his account of the conquest of Joppa, General Djehuty or Toth of pharaoh Thutmose III of Egypt (around 1440 BC) asks at some point that his horses be taken inside the city, lest they be stolen by a passing Apir.

On two stelae at Memphis and Karnak, Thutmose III's son Amenhotep II boasts of having made 89,600 prisoners in his campaign in Canaan (around 1420 BC), including "127 princes and 179 nobles(?) of Retenu, 3600 Apiru, 15,200 Shasu, 36,600 Hurrians", etc.

A stela from the reign of Seti I (around 1300 BC) tells that the pharaoh sent an expedition into the Levant, in response to an attack of "the apiru from Mount Yarmuta" upon a local town.

A list of goods bequeathed to several temples by Pharaoh Ramesses III (around 1160 BC) includes many serfs, Egyptian and foreign: 86,486 to Thebes (2607 foreigners), 12,364 to Heliopolis (2093 foreign), and 3079 to Memphis (205 foreign). The foreign serfs are described as "maryanu (soldiers), apiru, and people already settled in the temple estate".

The laborers that Ramesses IV sent to the quarry of Wadi Hammamat in his third year (ca. 1154–1158 BCE) included 5,000 soldiers, 2,000 men attached to the temples of Pharaoh as well as 800 Apiru.[12] This is the last known reference to the Apiru in Egyptian documents.

Hittite sources

The SA.GAZ are mentioned in at least a dozen documents from the Hittite kingdom, starting from 1500 BC or earlier. Several documents contain the phrase "the troops from Hatti and the SA.GAZ troops", Hatti being the core region of the Hittite kingdom.

Two oaths from the reigns of Suppiluliuma (probably Suppiluliuma I, reigned ca. 1358 BC to 1323 BC) and Mursilis II (around 1300 BC) invoke, among a long list of deities, "...the Lulahhi gods (and) the Hapiri gods, Ereshkigal, the gods and goddesses of the Hatti land, the gods and goddesses of Amurru land, ...".

Another mention occurs in a treaty between kings Duppi-Teshub of Amurru and Tudhaliya of Carchemish, arbitrated by Mursili II. The Hittite monarch recalls how he had restored king Abiradda to the throne of Jaruwatta, a town in the land of Barga, which had been captured by the Hurrians and given to "the grandfather of Tette, the SA.GAZ".

Another text record the existence of a Habiru settlement somewhere near a Hittite temple; one from Tahurpa names two female SA.GAZ singers.

Mitanni sources

An inscription on a statue found at Alalakh in southeastern Anatolia the Mitanni prince Idrimi of Aleppo (who lived from about 1500 BC to 1450 BC), tells that, after his family had been forced to flee to Emar, he left them and joined the "Hapiru people" in "Ammija in the land of Canaan". The Hapiru recognized him as the "son of their overlord" and "gathered around him;" they are said to include "natives of Halab, of the country of Mukish, of the country Nihi and also warriors from the country Amae." After living among them for seven years, he led his Habiru warriors in a successful attack by sea on the city-state of Alalakh, where he became king.

Several detailed lists of SA.GAZ troops have been found on the same site, enumerating eighty in all. Their names are predominantly Hurrian; seven are perhaps Semitic. They come from a variety of settlements scattered around the region. One had been a thief, another a slave, two others, priests; most became infantry, a handful were charioteers, one a messenger.

Like the SA.GAZ soldiers of the earlier Mesopotamian city-states, they received payment, or perhaps rations, in the form of sheep. A general enumeration of SA.GAZ soldiers within the city counts 1436 in all.

At Nuzi in Mesopotamia, documents from the household of an official named Tehiptilla record a number of Habiru voluntarily entering long-term service in exchange for food, clothing, and shelter.[14] Public records from the same city tally handouts of food and clothing to Habiru, the former to groups, the latter to individuals. One is given feed for a horse, perhaps indicating a military role. Another document allocates Habiru laborers to various individuals.

The local population was predominantly Hurrian, while approximately 2/3 of the Habiru names are Semitic; of these, all are East Semitic (Akkadian), none West Semitic.

Ugarit

In the port town of Ugarit in northern Syria, a cuneiform tablet that was still being baked when the city was destroyed (around 1200 BC) mentions the PRM (which are assumed to be the Hapiru, -M being the Ugaritic plural suffix). Tax lists from the city record the existence of "Aleppo of the PRM" (in Ugaritic) and "Aleppo of the SA.GAZ" (in Akkadian; the logogram is slightly modified from the usual SA.GAZ).

Being found in lists of four Aleppos that are otherwise the same, these are certainly the same location, but it is unclear whether they are separate settlements or quarters of one city.

Habiru and the biblical Hebrews

Since the discovery of the 2nd millennium inscriptions mentioning the Habiru there have been many theories linking these to the Hebrews of the Bible.

Encyclopædia Britannica states: "Many scholars feel that among the Hapiru were the original Hebrews, of whom the later Israelites were only one branch or confederation."[15]

Anson Rainey has argued that "the plethora of attempts to relate apiru (Habiru) to the gentilic ibri are all nothing but wishful thinking."[16] The Zondervan Illustrated Bible Dictionary states that Habiru is not an ethnic identification and is used to refer to both Semites and non-Semites, adding that "the connection, if there is any, remains obscure."[17]

See also

Notes

- ↑ (William H McNeil and Jean W Sedlar, in "The Ancient Near East" discuss the etymology of the name habiru and references to it in the Amarna letters and Egyptian campaign literature.)

- ↑ "Dictionary and Thesaurus - Merriam-Webster".

- ↑ "the definition of Habiru".

- ↑ Carol A. Redmount, 'Bitter Lives: Israel in and out of Egypt' in The Oxford History of the Biblical World, ed: Michael D. Coogan, (Oxford University Press: 1999), p.98

- 1 2 Redmount, p.98

- ↑ Rainey, Anson (November 2008). "Shasu or Habiru. Who Were the Early Israelites?". Biblical Archeology Review. Biblical Archaeology Society. 34 (06 (Nov/Dec)).

- ↑ Mendenhall, George E; Huffmon, H.B.; Spina, F.A.; Green, Alberto R.W. (1982). The Quest for the Kingdom of God: studies in honor of George E. Mendenhall. Eisenbrauns. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-931464-15-7.

- ↑ citation(s) needed

- ↑ "PSD: home page".

- ↑ Citations needed for this section

- ↑ An Egyptian Hieroglyphic Dictionary, in Two Volumes, Budge, Sir E.A.Wallis.; p.119, Vol. 1; Dover Publications, Inc. New York; © 1920

- ↑ A.J. Peden, The Reign of Ramesses IV, (Aris & Phillips Ltd: 1994), pp.86-89

- ↑ Citations needed for this section

- ↑ http://rbedrosian.com/Ref/Speiser/Speiser_1927_Kirkuk.pdf

- ↑ The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. "Canaan: Historical region, Middle East". Encyclopædia Britannica: School and Library Subscribers. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ↑ Anson F. Rainey, Unruly Elements in Late Bronze Canaanite Society, in "Pomegranates and golden bells" ed. David Pearson Wright, David Noel Freedman, Avi Hurvitz, (Eisenbrauns, 1995) p.483

- ↑ Douglas, J.D. (2011). Zondervan Illustrated Bible Dictionary. Zondervan. p. 557. ISBN 978-0310229834.

Further reading

- W.F. Albright, "The Amarna Letters from Palestine," Cambridge Ancient History, vol. 2.

- Robert D. Biggs, (Review of Salvini). Journal of Near Eastern Studies 58 (4), October 1999, p294.

- Robert Drews, The Coming of the Greeks: Indo-European Conquests in the Aegean and the Near East, Princeton, 1988. ISBN 0-691-03592-X

- Robert Drews, The End of the Bronze Age: Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe ca. 1200 B.C., Princeton, 1993. ISBN 0-691-02591-6

- Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman, The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of its Sacred Texts. 2003

- Moshe Greenberg, The Hab/piru, American Oriental Society, New Haven, 1955.

- Walter Harrelson (February 1957). Wright, G.E., ed. "Part I. Shechem in Extra-Biblical References". Biblical Archaeologist. The American Schools of Oriental Research. 20 (1): 2–10. JSTOR 3209166. doi:10.2307/3209166.

- George E. Mendenhall, Ancient Israel's Faith and History: An Introduction to the Bible in Context, Westminster John Knox Press, 2001.

- George E. Mendenhall, The Tenth Generation: The Origins of the Biblical Tradition, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973.

- Oxford History of the Biblical World, page 72. ISBN 0-19-513937-2

- James B. Pritchard, Ed. Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, Second Edition. Princeton, 1955.

- Forrest Reinhold, Hurrian Hebrews; Ea as Yahweh; The Origins Of The Hebrews & "The Lord Iowa, 2000.

- George Roux, Ancient Iraq, third edition 1992 ISBN 0-14-012523-X

- Mirjo Salvini, The Habiru prism of King Tunip-Teʔʔup of Tikunani. Istituti Editoriali e Poligrafici Internazionali, Rome (1996). ISBN 88-8147-093-4

- Daniel C. Snell, Life in the Ancient Near East, Yale, 1997. ISBN 0-300-06615-5

- Eveline J. van der Steen, Tribes and Territories in Transition: The Central East Jordan Valley: A Study of the Sources, Peeters, 2003, ISBN 978-90-429-1385-1

External links

![]() Media related to Habiru at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Habiru at Wikimedia Commons