HIV/AIDS in South Africa

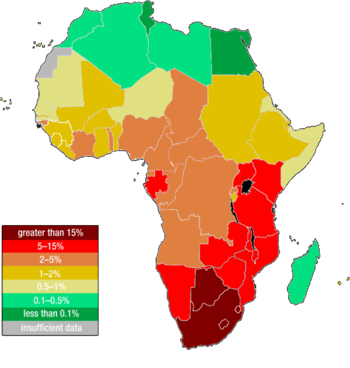

HIV/AIDS in South Africa is a prominent health concern; South Africa is believed to have more people with HIV/AIDS than any other country in the world.

The 2007 UNAIDS report estimated that 5,700,000 South Africans had HIV/AIDS, or just under 12% of South Africa's population of 48 million.[1] In the adult population the rate is 18.5%.[2] The number of infected is larger than in any other single country in the world. The other top five countries with the highest HIV/AIDS prevalence are all neighbours of South Africa.

In 2010, only 88% of people in South Africa with advanced HIV/AIDS were receiving anti-retroviral treatment (ART). In 2004, 2005 and 2006 the figures were 4%, 15% and 21% respectively.[3] By 2009, nearly 1 million or about 2% of all adult South Africans were receiving ART.[4]

In 2010, an estimated 280,000 South Africans died from the effects of HIV/AIDS. In ten years preceding, it is estimated that between 42% and 47% of all deaths among South Africans were HIV/AIDS deaths.[5] However, the Death Notification Forms Survey of 2010, which estimates a 93% completion rate, shows that out of a total of 543,856 deaths nationwide (Appendix C4), only 18,325 deaths were attributed to HIV/AIDS Diseases (B20-B24, Table 4.5).[6]

Although new infections among mature age groups in South Africa remain high, new infections among teenagers seem to be on the decline. HIV/AIDS prevalence figures in the 15–19 year age group for 2005, 2006 and 2007 were 16%, 14% and 13% respectively.[7]

Prevalence

The Human Sciences Research Council, a South African institution, estimates 10.9% of all South Africans have HIV/AIDS.[8] Additionally, the Central Intelligence Agency estimates that 310,000 individuals died in South Africa from HIV/AIDS in the year 2009.[2] The rising prevalence rate has increased from 10.6% in 2008 to 12.2% in 2012. In 2012 alone, the Human Science Research Council (HSRC), reported 470,000 new diagnoses—or nearly 1,100 new infections every day. That's 100,000 more than was seen just one year earlier in 2011. Driving these statistics is the decreasing, rather than increasing, public knowledge about HIV. According to the HSRC report, only 26.8% of the 38,000 people surveyed understood how HIV was transmitted or ways to prevent it. That's down from 30.3% in 2008, with evidence showing that South Africans under 50 are having an increasing number of sexual partners and lower condom use.

According to the latest data from UNICEF, Eastern and Southern Africa currently have 5% of the world’s population but 50% of people living with HIV. The region also has 48% of new HIV infections among adults, 55% among children, and 48% of AIDS related deaths. South Africa alone has 5.6 million people living with HIV, or 17.3% of its population. More specifically, the Southern-Africa sub-region is the most severely affected by the epidemic. Three of the countries in this region have the highest prevalence rates in the entire world. Swaziland is the highest at 26%, Botswana has 23.4%, and Lesotho has 23.3% (UNICEF).

By race

A 2008 study revealed that HIV/AIDS infection in South Africa was distinctly divided along racial lines: 13.6% of black Africans in South Africa are HIV-positive, whereas only 0.3% of whites living in South Africa have the disease.[9] False traditional beliefs about HIV/AIDS, which contribute to the spread of the disease, persist in townships due to the lack of education and awareness programmes in these regions. Sexual violence and local attitudes toward HIV/AIDS have also amplified the epidemic.

By gender

HIV/AIDS is more prevalent among females, especially those under the age of 40. Women made up roughly 4 in every 5 people with HIV/AIDS aged 20–24, and 2 out of 3 of those aged 25–29. Although prevalence is higher among women in general, only 1 in every 6 HIV/AIDS infected people with multiple sex partners are women.

By pregnant women

HIV prevalence among pregnant women is highest in the populous KwaZulu-Natal province (37%), and lowest in the Western Cape (13%), Northern Cape (16%) and Limpopo (18%) provinces. In the five other provinces (Eastern Cape, Free State, Gauteng, Mpumalanga and North West) at least 26% of women attending antenatal clinics in 2006 tested HIV-positive.

The latest HIV data collected at antenatal clinics suggest that HIV infection levels might be levelling off, with HIV prevalence in pregnant women at 30% in 2007, 29% in 2006, and 28% in 2005. The decrease in the percentage of young pregnant women (15–24 years) found to be infected with HIV also suggests a possible decline in the annual number of new infections.[10]

By age

Between 2005 and 2008, the number of older teenagers with HIV/AIDS has nearly halved.[8] Between 2002 and 2008, prevalence among South Africans over 20 years old have increased whereas the figure for those under 20 years old have dropped somewhat over the same period.[8]

Condom use is highest among the youth and lowest among old people. More than 80% of men and more than 70% of women under 25 years old use condoms, and slightly more than half of men and women aged 25–49 claim to use condoms.[8]

More than 30% of young adults and more than 80% of older adults are aware of the dangers posed by HIV/AIDS. Knowledge about HIV/AIDS is lowest among people older than 50 years—less than two thirds know the truth about the disease.[8]

By province

In 2008, more than half (55%) of all South Africans infected with HIV reside in the KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng provinces.[11]

Between 2005 and 2008, the total number of people infected with HIV/AIDS have increased in all of South Africa's provinces except KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng. Nevertheless, KwaZulu-Natal still has the highest infection rate at 15.5% In the province with the lowest infection rate, the Western Cape, the total number of people with HIV/AIDS doubled between 2005 and 2008.[8]

Condom use has increased twofold in all provinces between 2002 and 2008. The two provinces where condoms were least used in 2002 were also the provinces where condoms are least used in 2008, namely the Northern Cape and the Western Cape.[8]

HIV/AIDS prevalence among sexually active South Africans by province are:

- KwaZulu-Natal: 25.8%.

- Mpumalanga: 23.1%

- Free State: 18.5%

- North West: 17.7%

- Gauteng: 15.2%

- Eastern Cape: 15.2%

- Limpopo: 13.7%

- Northern Cape: 9.2%

- Western Cape: 5.3%

Economic impact

The comparison done in 2003 of the results from four forecasting methods predicted the difference between an HIV/AIDS scenario versus a no-HIV/AIDS scenario for annual growth rates between 2002 and 2015.[12] According to the study, real growth in GDP would be 0.6 percentage points lower than if there were no HIV/AIDS, but per-capita growth in GDP would be 0.9 percentage points higher. Growth in population would have been 1.5 percentage points lower, and growth of the labour force would be 1.2 percentage points lower, but the unemployment rate would be 0.9 percentage points lower as well.

The South African branch of the company Daimler-Chrysler estimated that in 2002 expenses related to HIV/AIDS were equivalent to 4% of all its salaries in South Africa.[13] A study done in 2000 by South Africa's second largest company, Sasol, indicated that 15% of its local workforce was HIV positive, of which 11% had AIDS.[14] According to the CEO of South Africa's largest company, SAB Miller, the cost of HIV/AIDS include costs associated with increased absenteeism, reduced productivity, increased turnover, and healthcare costs.[15]

Political Impact

HIV/AIDS poses a real threat to South Africa’s political structure. HIV/AIDS creates instability throughout a country, especially in the government and those in power. The disease can cause conflict and/or thrives in it. This fact has increasingly dangerous effects on economies and governments, which can lead to failing states. Failing states are often a hotbed for terrorism. Colin McInnes says in an International Affairs article that the mid 90s-beginning of the century was “marked by examples of failing states creating problems for international security, while in the wake of 9/II a link was drawn between failing states and international terrorism, notably by the Bush administration in the United States”.[16] The effects are not immediate as well, they linger as people get sicker and sicker and keep dying. A journal article by Robert Ostergard even says that people in the highest government positions are being brought down by the disease. He reports that “President Mugabe of Zimbabwe has admitted that three of his cabinet- level ministers have died from AIDS”.[17] When this happens (and it is more than likely happening in governments all over Africa), the policy making is disrupted and decision making is inconsistent. As bodies pile up, governments, militaries, communities, healthcare systems, and infrastructures crumble.

Military Impact

HIV/AIDS is also a military threat, and not just a healthcare crisis, because “it has become an 'accepted assumption ... that the rates of HIV are higher among the military and other uniformed forces than among the general population”.[16] It has been reported that at one point in time, military members were between 2-3 and 2-5 times more likely to be infected than the general population. These numbers rise even further during times of conflict. One of the main reasons that has been attributed to this group being affected more is that the military is composed mostly of sexually active 15-24 year olds, which is the demographic most at risk of contracting the disease. Drugs, peer pressure, and access to sex workers compounds the danger of contracting HIV/AIDS, while rape as a weapon of terror also spreads HIV/AIDS. This threatens national security because of a host of issues: “Flight times in African militaries have been significantly affected because crew have been too ill to fly; there is concern that soldiers may be wary of helping comrades with blood injuries in combat through fear of infection; and unit cohesion may suffer if some members are HIV-positive and others are not. The high rate of infection among the officer corps and NCOs will not only affect leadership and experience, but may mean the loss of informal networks crucial to the efficient operation of complex institutions such as the military".[16]

These effects of HIV/AIDS on military forces make an already unstable region even weaker.

Awareness campaigns

The four main HIV/AIDS awareness campaigns in South Africa are Khomanani (funded by the government), LoveLife (primarily privately funded), Soul City (a television drama for adults) and Soul Buddyz (a television series for teenagers).[18] Soul City and Soul Buddyz are the most successful campaigns although both campaigns experienced a slight loss of effectiveness between 2005 and 2008. Khomanani is the least successful campaign, although its effectiveness has increased by more than 50% between 2005 and 2008.

The dubious quality of condoms which are distributed is a setback to these efforts. In 2007, the government recalled more than 20 million locally manufactured condoms which were defective. Some of the contraceptive devices given away at the ANC's centenary celebrations in 2012 failed the water test conducted by the Treatment Action Campaign.[19]

Co-infection with tuberculosis

In 2007, it was estimated that one third of HIV infected people will develop TB (tuberculosis) in their lifetimes. In 2006, 40% of TB patients were tested for HIV. It has been the government policy since 2002 to cross-check all new cases of TB for HIV infection.[20]

Although STI prevention is part of the government's HIV/AIDS programmes, as it is in that of most countries, in South Africa HIV/AIDS prevention is done in conjunction with TB prevention. Most patients who die from HIV-related causes die from TB or similar illnesses. In fact the Health Department's programme of prevention is called the "National HIV and AIDS and TB Programme".[21] In line with United Nations requirements, South Africa has also drawn up an "HIV & AIDS and STI Strategic Plan".[22]

History of HIV/AIDS in South Africa

In 1983, AIDS was diagnosed for the first time in two patients in South Africa.[23] The first recorded death owing to AIDS occurred in 1983.[23] By 1986, there were 46 recorded AIDS diagnoses. Estimates from 2000 indicated that 5% of actual infections and only 1% of actual deaths due to AIDS were reported prior to 1990. Prior to 1990, AIDS was more common among men who have sex with men. By 1990, less than 1% of South Africans had AIDS. By 1996, the figure stood at around 3% and by 1999 the figure had reached 10%.[24] AIDS infection started reaching pandemic proportions around 1995.[25]

1960s

The earliest cases of HIV in Africa were discovered in the 1960s (Poku).

1970s

This is the decade when the true HIV/AIDS epidemic broke out (Poku).

1985

In 1985, the South African government set up the country’s first AIDS Advisory Group.

1990

In 1990, the first national antenatal survey to test for HIV found that 0.8% of pregnant women were HIV-positive. It was estimated that there were between 74,000 and 6,500,135 people in South Africa living with HIV. Antenatal surveys have subsequently been carried out annually.

1993

In 1993, the HIV prevalence rate among pregnant women was 4.3%. By 1993 the National Health Department reported that the number of recorded HIV infections had increased by 60% in the previous two years and the number was expected to double in 1993.

1995

In August 1995, the Department of Health awarded a R14.27 million contract to produce a sequel to the musical, Sarafina, about AIDS that would reach young people.[26] The project was dogged by controversy, and was finally shelved in 1996.[27]

From 6–10 March 1995, the 7th International Conference for People Living with HIV and AIDS was held in Cape Town, South Africa.[28] The conference was opened by then-Deputy President Thabo Mbeki.[29]

1996

In January 1996, it was decided that South Africa's national soccer team, Bafana-Bafana, would contribute to the AIDS Awareness Campaign by wearing red ribbons to all their public appearances during the African Nations Cup.[30]

On 5 July 1996,[31] South Africa's health minister Nkosazana Zuma spoke at the 11th International Conference on AIDS in Vancouver. She said:

- Most people infected with HIV live in Africa, where therapies involving combinations of expensive anti-viral drugs are out of the question.[32]

1997

In February 1997, South African government's Health Department defended its support for the controversial AIDS drug Virodene by stating that "the `cocktails' that are available [for the treatment of HIV/AIDS] are way beyond the means of most patients [even from developed countries]".[33] Parliament had previously launched an investigation into the procedural soundness of the clinical trials for the drug.[34]

1999

In 1999, the South African HIV prevention campaign loveLife is founded.

2000

In 2000, the Department of Health outlined a five-year plan to combat AIDS, HIV and STIs. A National AIDS Council (SANAC) was set up to oversee these developments.

2001

The South African government successfully defended against a legal action brought by transnational pharmaceutical companies in April 2001 of a law that would allow cheaper locally produced medicines, including anti-retrovirals, although the government's roll-out of anti-retrovirals remained generally slow.

In 2001, Right to Care, an NGO dedicated to the prevention and treatment of HIV and associated diseases, was founded. Using USAID's PEPFAR funding, the organisation expanded rapidly and after ten years (2011) had over 125 000 HIV-positive patients in clinical care.

2002

In 2002, South Africa's High Court ordered the government to make the drug nevirapine available to pregnant women to help prevent mother to child transmission of HIV, following campaigns by Treatment Action Campaign and others.

Demographics

According to the National HIV and Syphilis Antenatal Sero-prevalence Survey of 2005[35] and 2007,[36] the percentage of pregnant women with HIV per year was as follows:

| Year: | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 [37] |

| Percentage: | 0.7 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 4.0 | 7.6 | 10.4 | 14.2 | 17.0 | 22.8 | 22.4 | 24.5 | 24.8 | 26.5 | 27.9 | 29.5 | 30.2 | 29.1 | 28.0 | 29.3 | 29.4 | 30.2 | 29.5 |

According to a 2006 study by The South African Department of Health, 13.3% of 9,950 Africans that were included in the poll had HIV. Out of 1,173 whites, 0.6% had HIV.[38] These numbers are confirmed in a 2008 study by the Human Sciences Research Council that found a 13.6% infection rate among Africans, 1.7% among Coloreds, 0.3% among Indians, and 0.3% among Whites.[39]

In 2007, it was estimated that between 4.9 and 6.6 million of South Africa's 48 million people of all ages were infected with HIV (human immunodeficiency virus), which is the virus that causes AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome).[40]

AIDS denialism in South Africa

- See also HIV/AIDS denialism in South Africa.

2000

On 9 July 2000, then President Thabo Mbeki opened the International AIDS Conference in Durban with a speech not about HIV or AIDS but about extreme poverty in Africa. In the speech, he confirmed his belief that immune deficiency is a big problem in Africa but that one can't possibly attribute all immune deficiency related diseases to a single virus.[41][42]

On 4 September 2000, Thabo Mbeki acknowledged during an interview with Time Magazine (South African edition) that HIV can cause AIDS but confirmed his opinion that HIV should not be regarded as the sole cause of immune deficiency. He said:

- ...the notion that immune deficiency is only acquired from a single virus cannot be sustained. Once you say immune deficiency is acquired from that virus, your response will be anti-retroviral drugs. But if you accept that there can be a variety of reasons ... then you can have a more comprehensive treatment response.[43][44]

On 20 September 2000, then President Thabo Mbeki responded to a question in Parliament about his views. He said:

- All HIV/AIDS programmes of this government are based on the thesis that HIV causes AIDS. [But...] can a virus cause a syndrome? ... It can't, because a syndrome is a group of diseases resulting from acquired immune deficiency. Indeed, HIV contributes [to the collapse of the immune system], but other things contribute as well.[45]

2001

In 2001 the government appointed a panel of scientists, including a number of AIDS denialists, to report back on the issue. The report suggested alternative treatments for HIV/AIDS, but the South African government responded that unless alternative scientific proof is obtained, it will continue to base its policy on the idea that the cause of AIDS is HIV.[46]

2003

Despite international drug companies offering free or cheap anti-retroviral drugs, the Health Ministry remained hesitant about providing treatment for people living with HIV. Only in November 2003 did the government approve a plan to make anti-retroviral treatment publicly available. Prior to 2003, South Africans with HIV who used the public sector health system could get treatment for opportunistic infections but could not get anti-retrovirals.[38]

2006

The effort to improve treatment of HIV/AIDS was damaged by the attitude of many figures in the government, including President Mbeki. The then health minister, Manto Tshabalala-Msimang, advocated a diet of garlic, olive oil and lemon to cure the disease.[47] Although many scientists and political figures called for her removal, she was not removed from office until Mbeki himself was removed from office.[48] These policies led to the deaths of over 300,000 South Africans.[49]

2007

In August 2007, President Mbeki and Health Minister Tshabalala-Msimang dismissed Deputy Health Minister Nozizwe Madlala-Routledge. Madlala-Routledge has been widely credited by medical professionals and AIDS activists.[50] Although she was officially dismissed for corruption, it was widely held that she was dismissed for her more mainstream beliefs about AIDS and its relation with HIV.[51]

2013

The United States announced in March, 2013 that their support to South Africa will be cut in half by 2017 due to the economic crisis and compulsory budget cuts.[52]

The role of the media in South Africa's epidemic

The South African press took a strong advocacy position during the denialism era under Thabo Mbeki.[53][54] There are numerous examples of journalists taking the government to task for policy positions and public statements that were seen as irresponsible.[53] Some of these examples include: attacks on Health Minister Manto Tshabalala-Msimang’s “garlic and potato” approach to treatment,[55] outrage at Mbeki’s statement that he never knew anyone who had died of AIDS,[56] and coverage of the humiliating 2006 Global AIDS Conference.[57]

It could be claimed that the news media have taken a less aggressive stance since the end of Mbeki’s presidency and the death of Tshabalala Msimang. The emergence of Jacob Zuma as party and state leader heralded what the press saw as a new era of AIDS treatment.[58] However, this also means that HIV is afforded less news coverage. A recent study by the HIV/AIDS and the Media Project has shown that the quantity of HIV-related news coverage has declined dramatically from 2002/3 (what could be considered the pinnacle of government denialism) to the more recent “conflict resolution” phase under Zuma. Perhaps HIV has fallen into the traditional categories of being impersonal, undramatic, "old" news.[54] The number of health journalists has also declined considerably.[59]

See also

General:

References

- ↑ "page 214" (PDF). Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- 1 2 "South Africa - CIA - The World Factbook". https://www.cia.gov. 4 April 2007. External link in

|work=(help) - ↑ "page 271" (PDF). Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0302/P03022010.pdf page 5

- ↑ http://www.statssa.gov.za/publicationsd/P0302/P03022010.pdf page 8

- ↑ http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/p03093/p030932010.pdf Table 4.5

- ↑ "page 25-26" (PDF). Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "The HIV and AIDS epidemic in South Africa: Where are we?" (PDF). Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ "South Africa HIV & AIDS Statistics." AVERT. Web. 3 Mar. 2012. <http://www.avert.org/south-africa-hiv-aids-statistics.htm>.

- ↑ "The national hiv and syphilis prevalence survey south africa 2007". The South African Department of Health. Archived from the original on 10 October 2008. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- ↑ "Sub-Saharan Africa AIDS epidemic update. Regional Summary" (PDF). UNAIDS. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- ↑ "The Impact of HIV/AIDS on the South African Economy: A Review of Current Evidence" (PDF). TIPS. Retrieved 22 October 2008. table on page 23

- ↑ "GLOBAL HEALTH INITIATIVE. Private Sector Intervention Case Example" (PDF). Daimler-Chrysler. Retrieved 22 October 2008. page 2

- ↑ "page 14" (PDF). Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ "Graham Mackay, CEO, SABMiller , Global Business Coalition on HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria". Gbcimpact.org. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- 1 2 3 McInnes, C. (2006). HIV / AIDS and Security. International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-), 82(2), 315-326. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3569423

- ↑ Ostergard, R. (2002). Politics in the Hot Zone: AIDS and National Security in Africa. Third World Quarterly, 23(2), 333-350. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3993504

- ↑ "slide 33". Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ "South Africa recalls 1m ANC condoms: Scores of people given free condoms at the party's centenary celebrations have complained that they are faulty". The Guardian. 31 January 2012.

- ↑ "South Africa – Country Progress Report" (PDF). Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ "National HIV/AIDS and TB Unit, National Department of Health, Pretoria". Doh.gov.za. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ http://www.info.gov.za/otherdocs/2007/aidsplan2007/background.pdf

- 1 2 Ras GJ, Simson IW, Anderson R, Prozesky OW, Hamersma T. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. A report of 2 South African cases. S Afr Med J 1983 Jul 23; 64(4): 140–2.

- ↑ http://www.info.gov.za/otherdocs/2000/population/chap6.pdf

- ↑ "Epidemiology of HIV/AIDS in South Africa : Dr T Govender" (PDF). Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ "The Sarafina II Controversy". Healthlink.org.za. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ "Zuma'S Response To Sarafina Ii". Doh.gov.za. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ "International Conference for People Living with HIV and AIDS, Cape Town, South Africa, March 6–10; Pre- Conference for Wo". Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ http://70.84.171.10/~etools/newsbrief/1995/news0304

- ↑ "Bafana Endorses Aids Awareness Campaign". Info.gov.za. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ "AEGiS-BAR: Vancouver or bust". Aegis.org. 13 May 1996. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ HEARD :: Home Archived 19 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Dr. N C Zuma On Virodene Controversy". Info.gov.za. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ "Response To Virodene Investigation". Info.gov.za. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ "National HIV & Syphilis Antenatal Sero-Prevalence Survey in SA 2005" (PDF). Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ Archived 26 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ The 2011 National Antenatal Sentinel HIV & syphilus prevalence survey in South Africa, National Department of Health of South Africa http://www.doh.gov.za

- 1 2 "The South African Department of Health Study, 2006". Avert.org. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence, Behaviour and Communication Survey, 2008. Human Sciences Research Council. 2009. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-7969-2292-2. Archived from the original on 22 May 2010. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- ↑ "Epidemiological Fact Sheet on HIV and AIDS, 2008 (page 4 and 5)" (PDF). Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ "MBEKI: 13TH INTERNATIONAL AIDS CONFERENCE". Info.gov.za. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ "Controversy dogs Aids forum". BBC News. 10 July 2000. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ http://www.tac.org.za/newsletter/2000/ns000908.txt

- ↑ Vos, Pierre De (28 May 2009). "Thabo Mbeki’s strange relationship with the truth continues – Constitutionally Speaking". Constitutionallyspeaking.co.za. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ "How can a virus cause a syndrome? asks Mbeki". Aegis.com. 21 September 2000. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ "South African split over Aids". BBC News. 4 April 2001. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ Blandy, Fran (16 August 2006). "'Dr Beetroot' hits back at media over Aids exhibition". Mail & Guardian Online.

- ↑ Garlic AIDS cure minister sidelined, 12 Sep 2006

- ↑ Lewandowsky, Mann, Bauld, Hastings, Loftus. "http://www.psychologicalscience.org/index.php/publications/observer/2013/november-2013/the-subterranean-war-on-science.html". Observer. Association for psychological science. Retrieved 4 November 2013. External link in

|title=(help) - ↑ Mbeki Gives Reason for Firing Minister 12 August 2007

- ↑ Madlala-Routledge was 'set up': De Lille 8 August 2007

- ↑ Madapolitics. "Daunting Outlook for AIDS Crisis in South Africa". Madapolitics. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- 1 2 Malan, Mia (2006). "Shaping the conflict: factors influencing the representation of conflict around HIV/AIDS policy in the South African press". Mobilizing Media.

- 1 2 Finlay, A (December 2004). "Exposing AIDS:Media’s impact in South Africa". Communicare 23(2).

- ↑ "Zapiro cartoon". Zapiro.com. 15 February 2004. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ "We don't need red hrrings". Mg.co.za. 29 September 2003. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ "Manto defends AIDS policies". Mg.co.za. 21 August 2006. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ "President heralds new era". Unaids.org. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ Duncan, C (2009). "HIV in the print media: A comparative and retrospective print media monitoring analysis".

Further reading

- Pieter Fourie "The Political Management of HIV and AIDS in South Africa: One burden too many?" Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, ISBN 0-230-00667-1

- Fassin, Didier "When Bodies Remember: Experiences and Politics of AIDS in South Africa" University of California Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-520-25027-7

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to AIDS in South Africa. |

- AIDSPortal South Africa page – latest research, guidelines and case studies

- NewsHour: HIV/AIDS and TB in South Africa

- JournAIDS: A resource on HIV for South African media practitioners