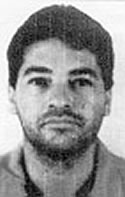

Hélmer Herrera

| Hélmer Herrera | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

August 24, 1951 Palmira, Valle del Cauca, Colombia |

| Died |

November 4, 1998 (aged 47) Palmira, Valle del Cauca, Colombia |

| Nationality | Colombian |

| Other names |

"Pacho" "H-7" |

| Occupation | Co-leader of the Cali Cartel |

| Criminal charge | Drug trafficking and money laundering |

| Criminal penalty | 6 years imprisonment |

Francisco Hélmer Herrera Buitrago also known as "Robapapas", "Pacho" and "H7", (August 24, 1951 in Palmira, Valle del Cauca – November 4, 1998 in Palmira, Valle del Cauca) was a Colombian drug trafficker, fourth in command in the Cali Cartel. Believed to be the son of Benjamin Herrera Zuleta.[1]

Early years

Herrera grew up in the Colombian town of Palmira in the Valle del Cauca Department. While in high school, Herrera studied technical maintenance, experience that got him a job later in the United States. While living in the United States he also became a jeweler and precious metals broker until he began selling cocaine in New York City. In 1975 and later in 1978 Herrera was arrested on distribution charges in New York City for selling cocaine.[2][3][4]

|

| Cali Cartel |

|---|

|

Gilberto Rodríguez Orejuela Miguel Rodríguez Orejuela José Santacruz Londoño Jorge Alberto Rodriguez Hélmer Herrera Buitrago Phanor Arizabaleta-Arzayus Mery Valencia Jairo Ivan Urdinola-Grajales Julio Fabio Urdinola-Grajales Henry Loaiza-Ceballos Victor Patiño-Fomeque Raul Grajales-Lemos Luis Grajales-Posso Juan Carlos Ortiz Escobar |

Cali Cartel

It is believed in 1983 Herrera went to Cali, Colombia to negotiate supply and distribution rights with the Cali Cartel for New York City. He would later open up trafficking routes for the Cali Cartel through Mexico with connection he had previously established. In conjunction with new trafficking routes, Herrera also ran one of the "... most sophisticated and profitable money laundering operations" according to the United States Drug Enforcement Administration.[4] Herrera was soon promoted to Cali cartel kingpin and given control over the southern Cali city of Jamundí and northern Cali cities Palmira and Yumbo.[5]

The Herrera operation according to the DEA involved importing cocaine base from Peru and Bolivia, which would be trafficked via his own transportation to conversion laboratories in Colombia. It is believed Herrera hired guerrilla forces such as Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (English: Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) (FARC) and then guerrilla group 19th of April Movement (Spanish: Movimiento 19 de Abril, M-19), to guard remote lab sites.[4]

Herrera always kept a very low profile and was never interviewed, and his name was almost never mentioned with that of the other leaders of the Cali cartel. While it has been argued that he was the source of most of the money involved in the illicit financing of Ernesto Samper's presidential campaign, Herrera himself never talked of the issue and was never formally involved in the investigation.[6] His name only came to light after a terrorist attack on a soccer field in Candelaria, Valle, on September 25, 1990, where 20 gunmen dressed in army and police attire opened fire on the crowd where Herrera was sitting, killing 18, however not hitting Herrera.[7][8] The attack was attributed to the Medellin cartel, and particularly to Pablo Escobar, who apparently blamed Herrera of being the author of a car bomb which exploded on January 13, 1988, in the Monaco building, an apartment building owned by Escobar in one of the most affluent areas in the city of Medellin. The war between the cartels shed lots of blood from both sides, but Herrera took a back role and left the fighting to the Rodriguez brothers.[7] Another attempt at his life was made on July 27, 1991, in a summer resort, where hooded gunmen wearing pink bracelets shot against the people in the place, killing 17 and hurting 13 others.[7] Herrera was always said to be the main financial provider for the Los Pepes organization, but even in that regard his name was never officially associated.[7]

Law enforcement actions

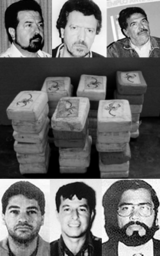

In November 1991, the DEA launched Operation Kingpin, of which two of Herreras' distribution cells in New York City were targeted. Through a large scale wiretap effort, the DEA utilized over 100 simultaneous, court-authorized wiretaps on cellular phones. At the close of Operation Kingpin close to 100 traffickers were arrested, more than $20 million in cash and assets were seized, and over 2.5 tons of cocaine seized. In addition records of transactions and personnel were seized from computers, that information later provided a greater look into the Cali Cartel cell structure.[9]

Surrender and Death

On September 1, 1996, Herrera turned himself in to the Search Bloc, (Spanish: Bloque de Busqueda), a unit of the Colombian National Police .[3] Herrera was the last of the seven leaders of the Cali Cartel to be captured.[4][5] He was sentenced to six years and eight months in prison for drug trafficking charges,[10] a sentence that was later extended to 14 years of prison in 1998.[7] Once in jail, Herrera reportedly changed his lifestyle and devoted himself to soccer, becoming the sports organizer in the jail, and sponsoring soccer tournaments. He also began a bachelor's degree in business administration.[6] Although he was supposed to be in the maximum security wing of the jail, Herrera visited the other wings, where he would meet with his lawyers. On November 4, 1998, Rafael Angel Uribe Serna, 32, got inside the jail and went to the soccer pitch where Herrera was playing. Uribe was reportedly drunk, but apparently Herrera stopped the game at seeing him and went to greet him. After hugging Herrera, Uribe took out a gun and shot him seven times in the head. Uribe was then caught by other inmates and then taken away by the prison guards, while Herrera was moved to a hospital where he died.[7]

There are a number of possible motives for Hererra's assassination. These include old vendettas from members of the Norte del Valle Cartel, in particular a man known by the alias of JJ, and Wilber Varela, who apparently had been the victim some days earlier of an assassination attempt by the Cali cartel leaders. Other hypotheses pointed out to Herrera's long-time conflict against communist guerrillas.[6] The assassin, Uribe, had been a personal adviser of Herrera for 10 years, and was a frequent visitor. Uribe declared that he had decided to kill Herrera because he had threatened Uribe's family when Uribe was unable to kill Víctor Carranza as Herrera had ordered. These declarations, however, were found unreliable, and probably a stratagem to take attention away from the real masterminds.[6][11] The most accepted hypothesis is that Uribe was actually acting under the orders of the Norte del Valle cartel who were angry with Herrera for having released information about them, and who had been eager to take up the business left behind after the capture or death of the Cali cartel leaders.[11] Uribe was also the uncle of brothers Luis Enrique and Javier Antonio Calle Serna, the "Comba" brothers, who took hold of the Norte del Valle cartel after Varela died. Uribe himself was assassinated in October, 2009.[12]

In popular culture

Herrera was portrayed by the actor Pedro Mogollón as the character of Hugo de la Cruz in TV Series El cartel. He was portrayed by the actor Daniel Rocha as the character of Gerardo Carrera in the TV Series Escobar, el patrón del mal. Finally, he was also portrayed by the actor Alberto Ammann in the Netflix series Narcos.

References

- ↑ Elaine Shannon Washington (June 24, 2001). "Cover Stories: New Kings of Coke". Time Magazine.

- ↑ "Los bienes de 'Pacho' Herrera" (in Spanish). El Tiempo. December 22, 2003. Archived from the original on May 16, 2004.

- 1 2 James R. Richards (1998). Transnational Criminal Organizations, Cybercrime, and Money Laundering: A Handbook for Law Enforcement Officers, Auditors, and Financial Investigators. CRC Press. pp. 21, 20.

- 1 2 3 4 "Surrender of Last Cali Mafia Leader". United States Drug Enforcement Administration. September 4, 1996.

- 1 2 Ron Chepesiuk (2003). The Bullet Or the Bribe: Taking Down Colombia's Cali Drug Cartel. Praeger Publishers. pp. 238, 25, 67.

- 1 2 3 4 Semana. "Otra guerra". Rafael Angel Uribe dice que mató a Helmer Herrera porque lo había amenazado, pero muy pocos le creen. Retrieved 2017-03-30.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Tiempo, Casa Editorial El. "FINAL DE UN CAPO QUE EMPEZÓ COMO MANDADERO". El Tiempo (in Spanish). Retrieved 2017-03-30.

- ↑ Dominic Streatfeild (2002). Cocaine: An Unauthorized Biography. Thomas Dunne Books. p. 360.

- ↑ DEA History: Part 2 (PDF). United States Drug Enforcement Administration. 2003.

- ↑ https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1998/11/06/colombian-drug-lord-shot-dead/98543888-faa4-4db0-a47d-237a24f90586/

- 1 2 Tiempo, Casa Editorial El. "BUSCAN A J.J. POR CRIMEN DE PACHO HERRERA". El Tiempo (in Spanish). Retrieved 2017-03-30.

- ↑ S.A., Nuevos Medios El País. "Se recrudece guerra del narcotráfico en Cali". historico.elpais.com.co (in Spanish). Retrieved 2017-03-30.