Juraj Košút

Juraj Košút (also Ďorď, Ďurko, Hungarian: György Kossuth, 1776 – 31 July 1849) was a Hungarian nobleman, a lawyer and a supporter of the Slovak national movement.

Family

He was baptized as Georgius Kosúth[lower-alpha 1] on 12 May 1776 in Necpaly (Necpál).[1][2] His father was Pavol (Paul) and his mother was Zuzana (Sus) Košút née Beniczky.[1] He had two brothers (Šimon and Ladislav/László) and one sister (Jana).[1]

The family lived for centuries in Košúty (Kossut). Their origin is dated back to the 13th century when king Béla IV of Hungary granted them nobility and the feod in Turiec (Turóc) in 1263. The surname means in Slovak "a billy goat" and a billy goat was also in their coat of arms. The family was a typical example of provincial gentry in the Kingdom of Hungary and was kindred with other families of the local gentry in the region of Turiec and Liptov (Liptó).[lower-alpha 2] The mother tongue of the Turiec branch of the family (including him and his brother László) was Slovak[3] and also the family archive contains only records in Slovak language together with official Latin documents.[lower-alpha 3][3] Brother László moved from Košúty to Monok and later became the father of Hungarian statesman Lajos Kossuth (Slovak: Ľudovít Košút).

The details of his childhood are not known. He studied law then he returned to the family estate. On 2 November 1803, he married Anna Zolnensis, but the couple had no children.[1] He spoke Slovak, Czech, Hungarian, Latin and German.

Work

His language skills, legal education and probably also the noble origin opened him many opportunities. He was an assesor in the County Court of Turiec (Turóc), a lay judge in Liptov (Liptó), Trenčín (Trencsén) and Orava (Árva) counties and a superintendent of Lutheran Church in Záturčie. The preacher of Záturčie was Ján Kalinčiak, a Slovak nationalist and the father of Ján Kalinčiak - a member of Štúr's movement and one of the main representatives of Slovak romantic prose. According to the Slovak historian Parenička, the Kalinčiaks significantly influenced the development of his national awareness.[1]

He became active in the Slovak national movement in 1842 when the leading personality of the movement Ľudovít Štúr required government's approval for publication of Slovak political newspaper. Štúr had to prove sufficient social interest and that the journal would have enough readers. Štúr initially attached a petition signed by priests and seminarists from the Diocese of Nitra, but he did not succeed.[4] In the meantime, nobles in Turiec have received information about his activities. They sent him a letter in which they promised "to bear witness" about the need for Slovak political newspaper. Surprised Štúr figured out that they were led by "Košút, the uncle of that angry man from Pest [Lajos Kossuth]".[4]

Košút organized petitions in several waves. The first two (at the end of 1842) were signed by 152 signatories[5][lower-alpha 4] who confirmed their interest in Slovak newspaper (mostly lower nobles and officials).[1] He also noted that he collected signatures only from one part of the county and he could collect much more if necessary. The petitions had a significant impact and according to Štúr's coworker Jozef Miloslav Hurban, they directly influenced Štúr's decision to publish his newspaper in Slovak instead of Slovakized Czech (used as a literal language by Slovak protestants) and to define a new Slovak language standard instead of Kollár's biblical Czech and Bernolák's standard based on West-Slovak dialect. The new standard was based on Central-Slovak dialects spoken also in Turiec.

He began corresponding with Štúr and promised him to make every effort "for the good of his (own) Slovak nation".[1] In 1843, he organized the third petition signed by 675 signatories (according to Košút's letter to Pavol Jozefi).[5] The details about this petition are not known, but it should be signed both by Catholic and Protestant Church authorities and the secular authorities including the vice-ispán of Turiec.[5] He promoted a similar petition in the neighboring Liptov.

In 1844, the state authorities initiated steps to close the Department of the Czechoslovak Language and Literature in Pressburg (Prešporok, Pozsony, now Bratislava). Slovak activists reacted by fundraising campaigns to save the department. Košút organized the campaign among lower nobles in Turiec, but the department was closed. Štúr was later forced to leave Pressburg and Košút donated a part of the money collected to the Slovak students who decided to move with Štúr to Levoča (Lőcse). Later, he supported Slovak society Tatrín which played an important role in the Slovak cultural life. In 1845, Štúr finally get a permission to publish a political newspaper (Slovenskje národňje novini) and Košút contributed to the newspaper as a correspondent.[1]

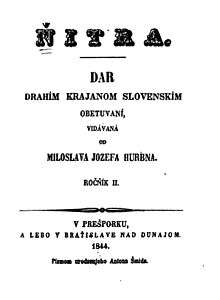

He became very popular in the Slovak national movement. Jozef Miloslav Hurban dedicated him the first book printed in Štúr's language standard and prominent Slovak poets Janko Kráľ and Janko Matuška (the author of the current Slovak anthem) wrote poems honoring him and his work.

In addition to his political activities, he inherited and administered the family estate in Košúty. He introduced several modern methods of agriculture in northern Upper Hungary (which is mostly today's Slovakia). He published his articles about agriculture in Nový i starý vlastenský kalendář (New and Old Patriotic Calendar) issued by his friend Gašpar Fejérpataky-Belopotocký.[1]

Relations to Lajos Kossuth

He was an uncle of politician Lajos Kossuth. As he did not have his own children his relation to Lajos was first very cordial and Lajos Kossuth regularly visited him in Turiec. But later when Lajos Kossuth entered political life and represented Hungarian (Magyar) interests, the relation between them was broken. Košút reproached him “a treason of the Slovak nation and Kossuth family” and the fact that Lajos Kossuth as a chief-editor of the Magyar newspaper Hírlap refused to publish his articles in which he was critical to the campaign of Magyarisation. He also used to criticize the political style of Lajos Kossuth. He considered it as hyperemotional, aggressive, thoughtless, hysterical and even “crazy.” His widow (Anna) in 1862 disinherited Lajos Kossuth and entailed the family possession to the children of Lajos Kossuth (Ferenc Lajos, Vilma and Lajos Tódor).

Notes

- ↑ The Latin form of his name.

- ↑ Beniczky de Benice, Rakovszky de Rákó, Raksánszky de Kisraksa, Záborszky de Zábor and Zatureczky de Zaturcsány.

- ↑ Slovak documents prevailed in the archive also in 1850s, after the Hungarian Revolution of 1848.

- ↑ Other sources mention 148 signatories. This number was mentioned already by Štúr's coworker Ján Francisci-Rimavský. The first petition (November 1942) was signed by 100 signatories, the second (December 1842) by 52.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Parenička 2014.

- ↑ "Slovakia Church and Synagogue Books, 1592-1910, database with images". FamilySearch. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- 1 2 Demmel 2012, p. 63.

- 1 2 Demmel 2012, p. 61.

- 1 2 3 Kovačka 2008, p. 19.

Bibliography

- Demmel, József (2015). "Spisovná slovenčina a uhorskoslovenské zemianstvo. Štúrovčina ako nástroj spoločenskej integrácie?" [Standard Slovak and Hungarian-Slovak low nobility. The Štúr language as an instrument of social integration?]. In Macho, Peter; Kodajová, Daniela. Ľudovít Štúr na hranici dvoch vekov (PDF) (in Slovak). Bratislava: Historický ústav SAV, VEDA, vydavateľstvo Slovenskej akadémie vied. ISBN 978-80-224-1454-8. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- Demmel, József (2012). ""Stav zemiansky národa slovenského". Uhorská šľachta slovenského pôvodu" ["The nobility of the nation of Slovaks…": The Nobility of Slovak Origin in the Kingdom of Hungary] (PDF). Forum Historiae (in Slovak). Bratislava: Historický ústav SAV (2). ISSN 1337-6861. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- Parenička, Pavol (14 November 1990). "Košút versus Kossuth". Slovenské národné noviny (in Slovak). Martin: Vydavateľstvo Matice slovenskej.

- Parenička, Pavol (13 August 2014). "Juraj Košút bol jednou z najpozoruhodnejších postáv slovenského národného hnutia" [Juraj Košút was one of the most notable figures of Slovak national movement]. Slovenské národné noviny (in Slovak). Martin: Vydavateľstvo Matice slovenskej. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- Parenička, Pavol (12 May 2015). "Štúrove Slovenskje národňje novini 1845 – 1848 – kapitoly z históri" [Štúr's Slovak National News 1845 – 1848 – chapters from history]. Slovenské národné noviny (in Slovak). Martin: Vydavateľstvo Matice slovenskej. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- Kovačka, Miloš (2008). "Memorialis Turčianskej stolice z roku 1707 v kontexte turčianskych výziev, proklamácií a memoránd do roku 1849" [Memorialis of Turiec County from 1707 in the context of Turiec manifetos, proclamations and memorandums]. In Kovačka, Miloš; Augustínová, Eva. Memorialis - historický spis slovenských stolíc. Zborník prác z medzinárodnej vedeckej konferencie, ktorá sa konala pri príležitosti 300. výročia tragických udalostí na počesť turčianskych martýrov Melchiora Rakovského a Krištofa Okoličániho 7. a 8. júna 2007 v Martine (PDF) (in Slovak). Martin: Slovenská národná knižnica. ISBN 978-80-89301-25-6. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

External links

- Košútovci

- Pavol Parenička: Košút versus Kossuth

- Kossuth és Petőfi, a szlovák nép két nagy gyermeke (in Hungarian)