Dracunculus medinensis

| Guinea worm | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Nematoda |

| Class: | Chromadorea |

| Order: | Spirurida |

| Superfamily: | Dracunculoidea |

| Family: | Dracunculidae |

| Genus: | Dracunculus |

| Species: | D. medinensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Dracunculus medinensis (Linnaeus, 1758) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Gordius medinensis Linnaeus, 1758 | |

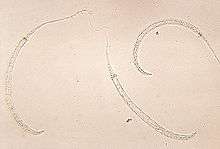

Dracunculus medinensis or Guinea worm is a nematode that causes dracunculiasis, also known as guinea worm disease.[1] The disease is caused by the female[2] which, at up to 800 mm (31 in) in length,[3] is among the longest nematodes infecting humans.[4] In contrast, the longest recorded male Guinea worm is only 40 mm (1.6 in).[3]

The common name "guinea worm" is derived from the Guinea region of Western Africa.

Life cycle

D. medinensis larvae are found in freshwater, where they are ingested by copepods of the genus Cyclops. Within the copepod, the D. medinensis larvae develop to an infective stage within 14 days.[5] When the infected copepod is ingested by a mammalian host, the copepod is dissolved by stomach acid and the D. medinensis larvae migrate through the wall of the mammalian intestine, and mature into adults. One hundred days after infection, a male and female D. medinensis meet and sexually reproduce within the host tissue. The male dies in the host tissue while the female migrates to the host's subcutaneous tissue. Approximately one year after infection, the female causes the formation of a blister on the skin's surface, generally on the lower extremities, though occasionally on the hand or scrotum. When the blister ruptures, the female slowly emerges over the course of several days or weeks.[5] This causes extreme pain and irritation to the host. When the host submerges the affected body part in water, the female expels thousands of larvae into the water. From here, the larvae infect copepods, continuing the life cycle.[5]

Removal

The female guinea worm slowly starts to emerge from the host's skin after the blister ruptures. The most common method for removing the worm involves submerging the affected body part in water to help coax the worm out. The site is then cleaned thoroughly. Then, slight pressure is applied to the worm as it is slowly pulled out of the wound. To avoid breaking the worm, pulling should stop when resistance is met. Full extraction of the female guinea worm usually takes several days. After each day's worth of extraction, the exposed portion of the worm is wrapped around a piece of rolled-up gauze or small stick to maintain tension.[6] This method of wrapping the worm around a stick or gauze is speculated to be the source for the Rod of Asclepius, the symbol of medicine.[7] Once secure, topical antibiotics are applied to affected region to help prevent secondary infections due to bacteria and then is wrapped in gauze to protect the wound. The same steps are repeated each day until the whole worm has been removed from the lesion.[6]

Eradication program

| Guinea worm cases by year [8][9][10][11] | ||

| Year | Reported Cases | Countries |

|---|---|---|

| 1986 | 3,500,000[12] | 16 |

| 1989 | 892,055 | 16 |

| 1995 | 129,852 | 19 |

| 2000 | 75,223 | 16 |

| 2001 | 63,717 | 16 |

| 2002 | 54,638 | 14 |

| 2003 | 32,193 | 13 |

| 2004 | 16,026 | 13 |

| 2005 | 10,674 | 12 |

| 2006 | 25,217[13] | 10 |

| 2007 | 9,585 | 9 |

| 2008 | 4,619 | 7 |

| 2009 | 3,190 | 5 |

| 2010 | 1,797 | 6 |

| 2011 | 1,060 | 4 |

| 2012 | 542 | 4 |

| 2013 | 148 | 5 |

| 2014 | 126 | 4 [14] |

| 2015 | 22 | 4 |

| 2016 | 25 | 3[15] |

In the 1980s, the Carter Center initiated a program to eradicate guinea worm.[16] The Guinea Worm Eradication campaign began in 1980 at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In 1984, the CDC was appointed as the World Health Organization Collaborating Center for research, training, and eradication of Dracunculus medinensis. There were 20 countries in 1986 that were affected by guinea worms. That year, WHO started the eradication program and the Carter Center took the lead on the effort.[6] The program included education of people in affected areas that the disease was caused by larvae in drinking water, isolation and support for sufferers, and – crucially – widespread distribution of net filters and pipe filters for drinking water, and education about the importance of using them.

As of 2015, the species has been reported to be near eradication.[16] The International Commission for the Certification of Dracunculus Eradication (ICCDE) has certified 198 countries, territories, and other WHO represented areas. In January 2015, eight countries remained to be certified as Dracunculus medinensis free. These eight countries include Angola, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya, Sudan, Chad, Ethiopia, Mali, and South Sudan. Of these, Chad, Ethiopia, Mali, and South Sudan are the only remaining endemic countries.[6] Not coincidentally, all four are affected by civil wars which affect the safety of health workers.

Other animals

However, as of 2016 there have been more than 500 dogs in Chad, 13 in Ethiopia and one dog in Mali and South Sudan, respectively, diagnosed with guinea worm.[17] Furthermore, it has been possible to infect frogs under laboratory conditions and recently natural infection has been reported in wild frogs in Chad.[18] These findings are a potential problem for the eradication programme.

Etymology

Dracunculus medinensis (little dragon from Medina) is a parasitic nematode that infects humans and domestic animals through contaminated water. D. medinensis was described in Egypt as early as the 15th century BCE and may have been the "fiery serpent" of the Israelites described in the Bible.[19]

See also

References

- ↑ Stefanie Knopp; Ignace K. Amegbo; David M. Hamm; Hartwig Schulz-Key; Meba Banla; Peter T. Soboslay (March 2008). "Antibody and cytokine responses in Dracunculus medinensis patients at distinct states of infection". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 102 (3): 277–283. PMID 18258273. doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.12.003.

- ↑ Langbong Bimi (2007). "Potential vector species of Guinea worm (Dracunculus medinensis) in Northern Ghana". Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases. 7 (3): 324–329. PMID 17767406. doi:10.1089/vbz.2006.0622.

- 1 2 G. D. Schmidt; L S. Roberts (2009). Larry S. Roberts; John Janovy, Jr., eds. Foundations of Parasitology (8th ed.). McGraw-Hill. pp. 480–484. ISBN 978-0-07-128458-5.

- ↑ Talha Bin Saleem; Irfan Ahmed (2006). ""Serpent" in the breast" (PDF). Journal of Ayub Medical College Abbottabad. 18 (4): 67–68. PMID 17591014.

- 1 2 3 "Dracunculiasis: About Guinea-Worm Disease". World Health Organization. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "Centers for Disease Control and Prevention". Parasites – Dracunculiasis (also known as Guinea Worm Disease). Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ↑ Satin, Morton (2007). Death in the Pot: The Impact of Food Poisoning on History. Amherst: Prometheus Books. pp. 63–65.

- ↑ WHO. "Dracunculiasis Epidemiological Data (1989-2008)" (PDF). World Health Organization. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

- ↑ WHO. "WHO Weekly Epidemiology Record 86, issue 10". Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- ↑ Carter Center. "Guinea Worm Wrap up 209" (PDF).

- ↑ "Guinea Worm Disease: Case Countdown". Carter Center.

- ↑ https://www.1843magazine.com/content/features/tom-whipple/good-riddance

- ↑ Increase in reported cases resulted from improved reporting in southern Sudan following the peace agreement in 2005 "Progress Toward Global Eradication of Dracunculiasis, January 2005--May 2007 [sic]". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 56 (32): 813–817. 2007. Retrieved 2011-03-16.

- ↑ "Carter Center: 126 Cases of Guinea Worm Disease Remain Worldwide". Retrieved 2015-05-09.

- ↑ "Carter: Guinea Worm disease reported in 3 countries in 2016". Associated Press. Retrieved 2017-01-11.

- 1 2 World Science Festival. "This Species Is Close to Extinction and That's a Good Thing". TIME.

- ↑ "Dracunculiasis (guinea-worm disease)". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2016-10-02.

- ↑ Eberhard, Mark L.; Cleveland, Christopher A.; Zirimwabagabo, Hubert; Yabsley, Michael J.; Ouakou, Philippe Tchindebet; Ruiz-Tiben, Ernesto. "Guinea Worm (Dracunculus medinensis) Infection in a Wild-Caught Frog, Chad". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 22 (11): 1961–1962. PMC 5088019

. PMID 27560598. doi:10.3201/eid2211.161332.

. PMID 27560598. doi:10.3201/eid2211.161332. - ↑ "Dracunculiasis: Historical background". World Health Organization. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

External links

Media related to Dracunculus medinensis at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Dracunculus medinensis at Wikimedia Commons- Donors Commit $240 Million to Fight Neglected Diseases

- How to Slay a Dragon – documentary by Clifford Bestall, broadcast on Al Jazeera English, Spring 2014 (video, 47 min.)