Cape Guardafui

| Cape Guardafui Ras Asir, Gardafuul راس عسير Aromata promontorium | |

|---|---|

|

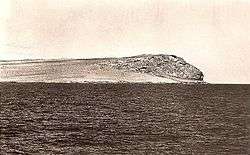

Cape Guardafui c. 1900 | |

Cape Guardafui location | |

| Country | |

| Region | Bari |

| Time zone | EAT (UTC+3) |

Cape Guardafui (Somali: Gees Gardafuul), also known as Ras Asir and historically as Aromata promontorium, is a headland in the autonomous Puntland region in Somalia. Coextensive with the Gardafuul administrative province, it forms the geographical apex of the Horn of Africa. Its shore at 51°27'52"E is the second easternmost point on mainland Africa after Ras Hafun.

Location

Cape Guardafui is located at 11°49′N 51°15′E / 11.817°N 51.250°E, near the Gulf of Aden. The archipelago of Socotra lies off the cape in the Indian Ocean.[1]

Fifteen leagues (45 miles) west of Guardafui is Ras Filuk, a steep cliff jutting into the Gulf of Aden from flatland. The mountain is believed to correspond with the ancient Elephas Mons or Cape Elephant (Ras Filuk in Arabic) described by Strabo.[2][3]

History

Referred to as Aromata promontorium by the ancient Greeks, Guardafui was described as early as the 1st century CE in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, along with other flourishing commercial settlements on the northern Somali littoral.[2]

The name Guardafui originated during the late Middle Ages by sailors using the Mediterranean Lingua Franca: "guarda fui" in ancient Italian means "look and escape", as a reference to the danger of the cape.[4]

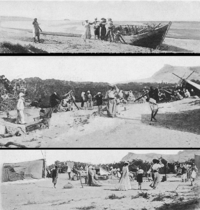

In the early 19th century, Somali seamen barred entry to their ports along the coast, while engaging in trade with Aden and Mocha in adjacent Yemen using their own vessels.[2]

Due to the frequency of shipwrecks in the treacherous seas near Cape Guardafui, the British signed an agreement with sultan Osman Mahamuud of the Majeerteen Sultanate, which controlled much of the northeastern Somali seaboard during the 19th century. The agreement stipulated that the British would pay annual subsidies to protect shipwrecked British crews and guard wrecks against plunder. The agreement, however, remained unratified, as the British feared that doing so would "give other powers a precedent for making agreements with the Somalis, who seemed ready to enter into relations with all comers."[5]

Sultan Yusuf Ali Kenadid of the Sultanate of Hobyo, which also controlled a portion of the coast, later granted concessions to an Aden-based French hotel proprietor and a former French Army officer to construct a lighthouse in Cape Guardafui. Capital for the project was raised by a firm in Marseilles, but the deal subsequently fell through.[6]

Lighthouse "Francesco Crispi"

Britain ceded to Italy sovereignty over the disputed region where is located Cape Guardafui in 1894. Starting in 1899, the Italians undertook detailed studies and surveys to build a lighthouse and the first concrete project came out in 1904. Italy wanted the construction and maintenance costs of the future lighthouse to be shared by the maritime powers which would benefit most from the new lighthouse but Britain, which suspected that Italy also intended to build a coaling station that would compete with Aden, finally refused to contribute.[7]

Thus, it is only in the early 1920s that the authorities of Italian Somaliland finally made good on their promise to build a lighthouse. The first one, inaugurated in April 1924 as the Francesco Crispi Lighthouse, was a simple, functional metal-framed lighthouse built atop the headland.[8] Simultaneously, a wireless station to monitor maritime traffic, which had been built in the nearly village of Tohen, was activated.

A large-scale rebellion against Italian rule in that part of Italian Somaliland was underway at the time and troops guarding the new lighthouse and the wireless station repelled two attacks by several hundred rebels in November 1925 and January 1926.[9]

The lighthouse had suffered some damages during the attacks and this was one of the reasons that prompted the authorities to build a stronger, stone and reinforced concrete lighthouse, which was inaugurated in 1930. The striking new lighthouse was built in the shape of an Italian fascist "Fascio littorio". The lighthouse, which is no longer in use, still has the huge stone axe blade characteristic of fascist symbolism.

A stone lighthouse and radio station were eventually built in the headland,[10] with the former named after Francesco Crispi in 1930.[11]

The lighthouse has an original "Fascio littorio" exterior stone as a decoration, that is typical of fascist architecture promoted by Benito Mussolini. Italian authorities have requested a study to declare the lighthouse an "historical monument" of Somalia and a proposed World Heritage Site [12]

Gardafuul Region

On April 8, 2013, the Puntland government announced the creation of a new region coextensive with Cape Guardafui named Gardafuul. Carved out of the Bari region, it consists of five districts (Baargaal, Bareeda, Alula, Muranyo and Gumbax) and has its capital at Alula. It is the largest region in Puntland, it has the longest coast(Indian Ocean and Gulf of Aden). The main resources of the region are: 1) Frankincense - produces more than 1.5 million kg of various types - Maydi, Beeyo, Falaxfalax and sweet gum (Xankookib). 2) Fish production is high, more than 50,000 tons of fish every month 3) Date Palm, in the region there are 258,000 date palm trees that, if developed, can produce enough dates to the entirety of Somalia 4) Coal deposit, high quantity and quality 5) Oil and gas - In Bina, Toxin, Afkalahaye and Geesalay. 6) 26 Natural water springs - along the escarpment there are natural water springs, if developed can aid in the development of the region.

Main projects: 1) International port at Guardafuul - from Alula to Olog and Damo. 2) International Airport 3) Developing main roads - Lafagoray, Gumayo, Dhabaqa and Hursale

See also

References

- ↑ Longhurst, Alan R. (2007). Ecological Geography of the Sea (second ed.). Burlington, Massachusetts: Academic Press. pp. 297–298. ISBN 978-0-0804-6557-9. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Tuckey, James Hingston, Commander, Royal Navy (1815). Maritime geography and statistics, or A description of the ocean and its coasts, maritime commerce, navigation, etc. Volume III. London: Printed for Black, Parry, and Co. p. 30. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- ↑ Strabo (1889). The geography of Strabo: Literary translated, with notes. translated by Hans Claude Hamilton & William Falconer. Volumes 74-76 of Bohn's classical library. G. Bell & sons. p. 200.

- ↑ Piratestan Archived March 13, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Laitin, David D. (1977). Politics, Language, and Thought: The Somali Experience. University Of Chicago Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-2264-6791-7.

- ↑ Committee on Northeast African Studies (1981). Northeast African Studies. Volume 3. Michigan State University Press. p. 50.

- ↑ http://www.lastampa.it/2014/04/06/cronaca/un-faro-torinese-contro-i-pirati-africani-ZufZUOUhwa4NPplnO3we3M/pagina.html

- ↑ https://farofrancescocrispicapeguardafui.wordpress.com/2014/01/29/1924-il-primo-faro-a-capo-guardafui/

- ↑ https://farofrancescocrispicapeguardafui.wordpress.com/2014/10/05/caduti-in-somalia-per-la-difesa-del-faro-francesco-crispi/

- ↑ Collier's Encyclopedia: With Bibliography and Index. Volume 9. New York: P.F. Collier & Son Corporation. 1957. p. 405.

- ↑ Bowditch, Nathaniel (1939). American Practical Navigator: An Epitome of Navigation and Nautical Astronomy. p. 352.

- ↑ Faro Francesco Crispi