Gryposuchus

| Gryposuchus Temporal range: Mid Miocene-Late Pleistocene (Friasian-Lujanian) ~15.97–0.012 Ma | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Crocodilia |

| Family: | Gavialidae |

| Subfamily: | †Gryposuchinae |

| Genus: | †Gryposuchus Gurich, 1912 |

| Species | |

| |

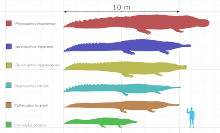

Gryposuchus is an extinct genus of gavialoid crocodilian. It is the type genus of the subfamily Gryposuchinae. Fossils have been found from Argentina, Colombia, Venezuela, Brazil and the Peruvian Amazon. The genus existed from the Middle Miocene to Late Pleistocene (Friasian to Lujanian).[1] One recently described species, G. croizati, grew to an estimated length of 10 metres (33 ft).

Species

The type species of Gryposuchus is G. neogaeus. Specimens from this species were first described from Argentina in 1885, although it was referred to Ramphostoma at the time.[2] It was assigned to the current genus in 1912 along with a newly described species, G. jessei.[3][4]

Another species, G. colombianus, has been recovered from deposits in Colombia that date back to the Miocene and Pliocene epochs. This species, named in 1965, was originally referred to Gavialis.[5] Fragmentary material of Gryposuchus from the Fitzcarrald Arch in the Peruvian Amazon dating back to the late middle Miocene bear a close resemblance to G. colombianus, but differ in rostrum proportions.[6]

Some skull material also recovered from Peruvian Amazon (Iquitos) in the Pebas Formation, has been named as Gryposuchus pachakamue in 2016 by Roberto Salas-Gismondi et al. It includes the holotype MUSM 987, a well preserved skull that lacks of temporal and occipital bones; it measures 623.2 millimeters in length, and a series of referred specimens, including possible juveniles. The species was named after the Quechuan word for a primordial god and "storyteller".[7] This new species is characterized by have 22 teeth in the mandible and the maxilla, a snout comparable in relative length to the modern Gavialis gangeticus, and is notable since that its orbits were wider than long and not so upturned as another species of gavialids, including the gryposuchines, which implies that G. pachakamue doesn't had the "telescoped" orbits (protruding eyes) condition fully developed. Since that it species, that inhabited the proto-Amazon fluvial system 13 million years ago, is the oldest record of gavialids in this area and it had a primitive telescoped eyes condition, it shows that the development of such condition was a case of convergent evolution with the species of Gavialis also found in fluvial environments.[7]

A species described in 2008, G. croizati, found from the upper Miocene Urumaco Formation in northwestern Venezuela, can be distinguished from other species of Gryposuchus on the basis of a reduced number of maxillary teeth, a slender parietal interfenestral bar, and widely separated and reduced palatine fenestrae, among other things. Based on measurements of the orbital cranial skeleton, the length of the animal has been estimated at around 10.15 m in length, with a total mass of about 1745 kg. Measuring the entire length of the skull from the end of the rostrum to the supraoccipital would result in a much larger size estimate, up to three times as great. However, because there is considerable variation seen in rostral proportions among crocodilians, the latter measurements are probably not an accurate way of estimating body mass and length.[8] Despite this, the species is still one of the largest crocodilians known to have existed, and it may indeed have been the largest gavialoid to have ever existed if a recent revision in the estimated size of the large tomistomine Rhamphosuchus is correct (the genus was once considered to be 15 m in length; the new estimate puts it at approximately 10 m).[9]

Paleobiology

Some gryposuchines such as Siquisiquesuchus and Piscogavialis have been found from localities thought to have been deposited in coastal environments.[10][11] The presence of Gryposuchus in the Urumaco Formation of Venezuela, which does include marine strata, lends credence to the idea that gryposuchines may have been living in coastal environments.[12][13] However, certain localities where material from the species G. colombianus has been recovered, such as La Venta, Colombia, were clearly deposited in non-marine environments, speaking against the proposed coastal lifestyle hypothesis for all gryposuchines.[14]

Distribution

Fossils of Gryposuchus have been found in:[1]

- Miocene

- Ituzaingó Formation, Argentina

- Solimões Formation, Brazil

- Honda Group, La Venta, Colombia

- Pebas Formation, Peru

- Urumaco Formation, Urumaco, Venezuela

- Pleistocene

References

- 1 2 Gryposuchus at Fossilworks.org

- ↑ Burmeister, G (1885). "Examen crítico de los mamíferos y los reptiles denominados pot Don Augusto Bravard". Anales del Museo Púbtico de Buenos Aires. 3: 95–173.

- ↑ Gurich, G (1912). "Gryposuchus jessei, ein neues schmalsnauziges Krokodil aus den jungeren Ablagerungen des oberen Amazonas-Gebietes". Jahr. Hamburg. Wissensch. Anst. 29: 59–71.

- ↑ Cozzuol, M. A. (2006). "The Acre vertebrate fauna: Age, diversity, and geography". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 21: 185–203. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2006.03.005.

- ↑ Langston, W (1965). "Fossil crocodilians from Colombia and the Cenozoic history of the Crocodilia in South America". University of California Publications in Geological Sciences. 52: 1–152.

- ↑ Salas-Gismondi, R., Antoine, P. O., Baby, P., Brusset, S., Benammi, M., Espurt, N., de Franceschi, D., Pujos, F., Tejada, J. and Urbina, M. (2007). Middle Miocene crocodiles from the Fitzcarrald Arch, Amazonian Peru. In: Díaz-Martínez, E. and Rábano, I. (eds.), 4th European Meeting on the Palaeontology and Stratigraphy of Latin America Cuadernos del Museo Geominero, nº 8. Instituto Geológico y Minero de España, Madrid.

- 1 2 Rodolfo Salas-Gismondi; John J. Flynn; Patrice Baby; Julia V. Tejada-Lara; Julien Claude; Pierre-Olivier Antoine (2016). "A New 13 Million Year Old Gavialoid Crocodylian from Proto-Amazonian Mega-Wetlands Reveals Parallel Evolutionary Trends in Skull Shape Linked to Longirostry". PLoS ONE. 11 (4): e0152453. PMC 4838223

. PMID 27097031. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0152453.

. PMID 27097031. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0152453. - ↑ Riff, D.; Aguilera, O. A. (2008). "The world's largest gharials Gryposuchus: description of G. croizati n. sp. (Crocodylia, Gavialidae) from the Upper Miocene Urumaco Formation, Venezuela". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 82 (2): 178–195. doi:10.1007/bf02988408.

- ↑ Head, J. J. (2001). Systematics and body size of the gigantic, enigmatic crocodyloid Rhamphosuchus crassidens, and the faunal history of Siwalik Group (Miocene) crocodylians. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 21(Supplement to No. 3):59A.

- ↑ Kraus, R (1998). "The cranium of Piscogavialis jugaliperforatus n. gen., n. sp. (Gavialidae, Crocodylia) from the Miocene of Peru". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 72: 389–406. doi:10.1007/bf02988368.

- ↑ Brochu, C. A.; Rincon, A. D. (2004). "A gavialoid crocodylian from the Lower Miocene of Venezuela". Special Papers in Palaeontology. 71: 61–78.

- ↑ Linares, O. J. (2004). "Bioestratigrafia de la fauna de mamiferos de las Formaciones Socorro, Urumaco y Codore (Mioceno Medio–Plioceno Temprano) de la region de Urumaco, Falcon, Venezuela". Paleobiologia Neotropical. 1: 1–26.

- ↑ Sánchez-Villagra, M. R.; Aguilera, O. A. (2006). "Neogene vertebrates from Urumaco, Falcón State, Venezuela: diversity and significance". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 4: 213–220. doi:10.1017/s1477201906001829.

- ↑ Kay, R. F. and Madden, R. H. (1997). Paleogeography and paleoecology. In: Kay, R. F., Madden, R. H, Cifelli, R. L., and Flynn, J. J., eds., Vertebrate paleontology in the neotropics: the Miocene fauna of La Venta, Colombia. Smithsonian Institution Press; Washington, DC. pp. 520–550.

.jpg)