Greater Germanic Reich

The Greater Germanic Reich (German: Großgermanisches Reich), fully styled the Greater Germanic Reich of the German Nation (German: Großgermanisches Reich Deutscher Nation) is the official state name of the political entity that Nazi Germany tried to establish in Europe during World War II.[2] Albert Speer stated in his memoirs that Hitler also referred to the envisioned state as the Teutonic Reich of the German Nation, although it is unclear whether Speer was using the now seldom used "Teutonic" as an English synonym for "Germanic".[3] Hitler also mentions a future Germanic State of the German Nation (German: Germanischer Staat Deutscher Nation) in Mein Kampf.[4]

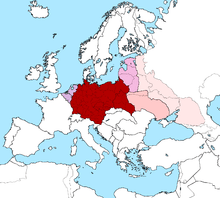

The territorial claims for the Greater Germanic Reich fluctuated over time. As early as the autumn of 1933, Hitler envisioned annexing such territories as Bohemia, Western Poland and Austria to Germany and creation of satellite or puppet states without economies or policies of their own.[5]

Between gaining power and February 1939, Hitler tried to conceal his true intentions towards Poland and revealed them only to his closest associates; the signing of a non-aggression pact with Poland in 1934 was a political maneuver to conceal his true intentions towards Poland.[6] From 1934 to early 1939, Nazi Germany secretly prepared for war against Poland and mass murder and ethnic cleansing of its population, while officially claiming to the Polish government that it would continue to guarantee Poland's existence (though still maintaining its claims on the Polish Corridor) and offer Poland the right to annex the entirety of Ukraine from the Soviet Union, should Poland support Germany in a war with the Soviet Union, while Germany would annex the Baltic states and Soviet territories.[7][8] Amidst and for a short time after German–Soviet negotiations for the partition of Poland between Germany and the Soviet Union took place, Hitler did not include territorial designs on the Soviet Union within the Greater Germanic Reich from 1939 to 1941, and instead was focusing on uniting the Germanic peoples of Scandinavia and the Low Countries into the Reich.[9]

This pan-Germanic Empire was expected to assimilate practically all of Germanic Europe into an enormously expanded Reich. Territorially speaking, this encompassed the already-enlarged German Reich itself (consisting of pre-1938 Germany proper, Austria, Bohemia, Moravia, Alsace-Lorraine, Eupen-Malmedy, Memel, Lower Styria, Upper Carniola, Southern Carinthia and German-occupied Poland), the Netherlands, the Flemish part of Belgium, Luxembourg, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Iceland, at least the German-speaking parts of Switzerland, and Liechtenstein.[10]

The most notable exception was the United Kingdom, which was not projected as having to be reduced to a German province but to instead become an allied seafaring partner of the Germans.[11] Another exception was German-populated territory in South Tyrol that was part of allied Italy. Aside from Germanic Europe, the Reich's western frontiers with France were to be reverted to those of the earlier Holy Roman Empire, which would have meant the complete annexation of all of Wallonia, French Switzerland, and large areas of northern and eastern France.[12] Additionally, the policy of Lebensraum planned mass expansion of Germany eastwards to the Ural Mountains.[13][14] Hitler planned for the "surplus" Russian population living west of the Urals to be deported to the east of the Urals.[15]

Ideological background

Racial theories

Nazi racial ideology regarded the Germanic peoples of Europe as belonging to a racially superior Nordic subset of the larger Aryan race, who were regarded as the only true culture-bearers of civilized society.[16] These peoples were viewed as either "true Germanic peoples" that had "lost their sense of racial pride", or as close racial relatives of the Germans.[17] German Chancellor Adolf Hitler also believed that the Ancient Greeks and Romans were the racial ancestors of the Germans, and the first torchbearers of "Nordic–Greek" art and culture.[18][19] He particularly expressed his admiration for Ancient Sparta, declaring it to have been the purest racial state:[20]

"The subjugation of 350,000 Helots by 6,000 Spartans was only possible because of the racial superiority of the Spartans." The Spartans had created "the first racialist state."[21]

Furthermore, Hitler's concept of "Germanic" did not simply refer to an ethnic, cultural, or linguistic group, but also to a distinctly biological one, the superior "Germanic blood" that he wanted to salvage from the control of the enemies of the Aryan race. He stated that Germany possessed more of these "Germanic elements" than any other country in the world, which he estimated as "four fifths of our people".[22]

Wherever Germanic blood is to be found anywhere in the world, we will take what is good for ourselves. With what the others have left, they will be unable to oppose the Germanic Empire.— Adolf Hitler, [23]

According to the Nazis, in addition to the Germanic peoples, individuals of seemingly non-Germanic nationality such as French, Polish, Walloon, Czech and so on might actually possess valuable Germanic blood, especially if they were of aristocratic or peasant stock.[23] In order to "recover" these "missing" Germanic elements, they had to be made conscious of their Germanic ancestry through the process of Germanization (the term used by the Nazis for this process was Umvolkung, "restoration to the race").[23] If the "recovery" was impossible, these individuals had to be destroyed to deny the enemy of using their superior blood against the Aryan race.[23] An example of this type of Nazi Germanization is the kidnapping of "racially valuable" Eastern European children.

On the very first page of Mein Kampf, Hitler openly declared his belief that "common blood belongs in a common Reich", elucidating the notion that the innate quality of race (as the Nazi movement perceived it) should hold precedence over "artificial" concepts such as national identity (including regional German identities such as Prussian and Bavarian) as the deciding factor for which people were "worthy" of being assimilated into a Greater German racial state (Ein Volk, Ein Reich, Ein Führer).[24] Part of the strategic methods which Hitler chose to ensure the present and future supremacy of the Aryan race (which was, according to Hitler, "gradually approaching extinction"[25]) was to do away with what he described as the "small state rubbish" (Kleinstaatengerümpel, compare Kleinstaaterei) in Europe in order to unite all these Nordic countries into one unified racial community.[26] From 1921 onward he advocated the creation of a "Germanic Reich of the German Nation".[2]

It was the continent which brought civilization to Great Britain and in turn enabled her to colonize large areas in the rest of the world. America is unthinkable without Europe. Why would we not have the necessary power to become one of the world's centres of attraction? A hundred-and-twenty million people of Germanic origin – if they have consolidated their position this will be a power against which no-one in the world could stand up to. The countries which form the Germanic world have only to gain from this. I can see that in my own case. My birth country is one of the most beautiful regions in the Reich, but what could it do if were left to its own devices? There is no possibility to develop one’s talents in countries like Austria or Saxony, Denmark or Switzerland. There is no foundation. That is why it is fortunate that potential new spaces are again opened for the Germanic peoples.— Adolf Hitler, 1942.[27]

Name

The chosen name for the projected empire was a deliberate reference to the Holy Roman Empire (of the German Nation) that existed in medieval times, known as the First Reich in National Socialist historiography.[28] Different aspects of the legacy of this medieval empire in German history were both celebrated and derided by the National Socialist government. Hitler admired the Frankish Emperor Charlemagne for his "cultural creativity", his powers of organization, and his renunciation of the rights of the individual.[28] He criticized the Holy Roman Emperors however for not pursuing an Ostpolitik (Eastern Policy) resembling his own, while being politically focused exclusively on the south.[28] After the Anschluss, Hitler ordered the old imperial regalia (the Imperial Crown, Imperial Sword, the Holy Lance and other items) residing in Vienna to be transferred to Nuremberg, where they were kept between 1424 and 1796.[29] Nuremberg, in addition to being the former unofficial capital of the Holy Roman Empire, was also the place of the Nuremberg rallies. The transfer of the regalia was thus done to both legitimize Hitler's Germany as the successor of the "Old Reich", but also weaken Vienna, the former imperial residence.[30]

After the 1939 German occupation of Bohemia, Hitler declared that the HRE had been "resurrected", although he secretly maintained his own empire to be better than the old "Roman" one.[31] Unlike the "uncomfortably internationalist Catholic empire of Barbarossa", the Germanic Reich of the German Nation would be racist and nationalist.[31] Rather than a return to the values of the Middle Ages, its establishment was to be "a push forward to a new golden age, in which the best aspects of the past would be combined with modern racist and nationalist thinking".[31]

The historical borders of the Holy Empire were also used as grounds for territorial revisionism by the NSDAP, laying claim to modern territories and states that were once part of it. Even before the war, Hitler had dreamed of reversing the Peace of Westphalia, which had given the territories of the Empire almost complete sovereignty.[32] On November 17, 1939, Reich Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary that the "total liquidation" of this historic treaty was the "great goal" of the Nazi regime,[32] and that since it had been signed in Münster, it would also be officially repealed in the same city.[33]

Pan-Germanism versus Pan-Germanicism

Despite intending to accord the other "Germanics" of Europe a racially superior status alongside the Germans themselves in an anticipated post-war racio-political order, the Nazis did not however consider granting the subject populations of these countries any national rights of their own.[16] The other Germanic countries were seen as mere extensions of Germany rather than individual units in any way,[16] and the Germans were unequivocally intended to remain the empire's "most powerful source of strength, from both an ideological as well as military standpoint".[27] Even Heinrich Himmler, who among the senior Nazis most staunchly supported the concept, could not shake off the idea of a hierarchical distinction between German Volk and Germanic Völker.[34] The SS's official newspaper, Das Schwarze Korps, never succeeded in reconciling the contradiction between Germanic 'brotherhood' and German superiority.[34] Members of Nazi-type parties in Germanic countries were also forbidden to attend public meetings of the Nazi Party when they visited Germany. After the Battle of Stalingrad this ban was lifted, but only if the attendees made prior notice of their arrival so that the events' speakers could be warned in advance not to make disparaging remarks about their country of origin.[35]

Although Hitler himself and Himmler's SS advocated for a pan-Germanic Empire, the objective was not universally held in the Nazi regime.[36] Goebbels and the Reich Foreign Ministry under Joachim von Ribbentrop inclined more towards an idea of a continental bloc under German rule, as represented by the Anti-Comintern Pact, Ribbentrop's "European Confederation" project and the earlier Mitteleuropa concept.

Germanic mysticism

There were also disagreements within the NSDAP leadership on the spiritual implications of cultivating a 'Germanic history' in their ideological program. Hitler was highly critical of Himmler's esoteric völkisch interpretation of the 'Germanic mission'. When Himmler denounced Charlemagne in a speech as "the butcher of the Saxons", Hitler stated that this was not a 'historical crime' but in fact a good thing, for the subjugation of Widukind had brought Western culture into what eventually became Germany.[37] He also disapproved of the pseudoarchaeological projects which Himmler organized through his Ahnenerbe organization, such as excavations of pre-historic Germanic sites:

Why do we call the whole world's attention to the fact that we have no past? It isn't enough that the Romans were erecting great buildings when our forefathers were still living in mud huts; now Himmler is starting to dig up these villages of mud huts and enthusing over every potsherd and stone axe he finds. All we prove by that is that we were still throwing stone hatchets and crouching around open fires when Greece and Rome had already reached the highest stage of culture. We really should do our best to keep quiet about this past. Instead Himmler makes a great fuss about it all. The present-day Romans must be having a laugh at these relegations.— Adolf Hitler, [37]

In an attempt to eventually supplant Christianity with a religion more amenable to National Socialist ideology, Himmler, together with Alfred Rosenberg, sought to replace it with Germanic paganism (the indigenous traditional religion or Volksreligion of the Germanic peoples), of which the Japanese Shinto was seen as an almost perfect East Asian counterpart.[38] For this purpose they had ordered the construction of sites for the worship of Germanic cults in order to exchange Christian rituals for Germanic consecration ceremonies, which included different marriage and burial rites.[38] In Heinrich Heims' Adolf Hitler, Monologe im FHQ 1941-1944 (several editions, here Orbis Verlag, 2000), Hitler is quoted as having said on 14 October 1941: "It seems to be inexpressibly stupid to allow a revival of the cult of Odin/Wotan. Our old mythology of the gods was defunct, and incapable of revival, when Christianity came...the whole world of antiquity either followed philosophical systems on the one hand, or worshipped the gods. But in modern times it is undesirable that all humanity should make such a fool of itself."

Establishment strategy

The goal was first proclaimed publicly in the 1937 Nuremberg Rallies.[39] Hitler's last speech at this event ended with the words "The German nation has after all acquired its Germanic Reich", which elicited speculation in political circles of a 'new era' in Germany's foreign policy.[39] Several days before the event Hitler took Albert Speer aside when both were on their way to the former's Munich apartment with an entourage, and declared to him that "We will create a great empire. All the Germanic peoples will be included in it. It will begin in Norway and extend to northern Italy.[nb 1][40] I myself must carry this out. If only I keep my health!"[39] On April 9, 1940, as Germany invaded Denmark and Norway in Operation Weserübung, Hitler announced the establishment of the Germanic Reich:

Just as the Bismarck Empire arose from the year 1866, so too will the Greater Germanic Empire arise from this day.[32]

The establishment of the empire was to follow the model of the Austrian Anschluss of 1938, just carried out on a greater scale.[41] Goebbels emphasized in April 1940 that the annexed Germanic countries would have to undergo a similar "national revolution" as Germany herself did after the Machtergreifung, with an enforced rapid social and political "co-ordination" in accordance with Nazi principles and ideology (Gleichschaltung).[41]

The ultimate goal of the Gleichschaltung policy pursued in these parts of occupied Europe was to destroy the very concepts of individual states and nationalities, just as the concept of a separate Austrian state and national identity was repressed after the Anschluss through the establishment of new state and party districts.[42] The new empire was to no longer be a nation-state of the type that had emerged in the 19th century, but instead a "racially pure community".[32] It is for this reason that the German occupiers had no interest in transferring real power to the various far-right nationalist movements present in the occupied countries (such as Nasjonal Samling, the NSB, etc.) except for temporary reasons of Realpolitik, and instead actively supported radical collaborators who favored pan-Germanic unity (i.e. total integration to Germany) over provincial nationalism (for example DeVlag).[43] Unlike Austria and the Sudetenland however, the process was to take considerably longer.[44] Eventually these nationalities were to be merged with the Germans into a single ruling race, but Hitler stated that this prospect lay "a hundred or so years" in the future. During this interim period it was intended that the 'New Europe' would by run by Germans alone.[34] According to Speer, while Himmler intended to eventually Germanize these peoples completely, Hitler intended not to "infringe on their individuality" (that is, their native languages), so that in the future they would "add to the diversity and dynamism" of his empire.[45] The German language would be its lingua franca however, likening it to the status of English in the British Commonwealth.[45]

A primary agent used in stifling the local extreme nationalist elements was the Germanic SS, which initially merely consisted of local respective branches of the Allgemeine-SS in Belgium, Netherlands and Norway.[46] These groups were at first under the authority of their respective pro-National Socialist national commanders (De Clercq, Mussert and Quisling), and were intended to function within their own national territories only.[46] During the course of 1942, however, the Germanic SS was further transformed into a tool used by Himmler against the influence of the less extreme collaborating parties and their SA-style organizations, such as the Hird in Norway and the Weerbaarheidsafdeling in the Netherlands.[46][47] In the post-war Germanic Empire, these men were to form the new leadership cadre of their respective national territories.[48] To emphasize their pan-Germanic ideology, the Norges SS was now renamed the Germanske SS Norge, the Nederlandsche SS the Germaansche SS in Nederland and the Algemeene-SS Vlaanderen the Germaansche SS in Vlaanderen. The men of these groups no longer swore allegiance to their respective national leaders, but to the germanischer Führer ("Germanic Führer"), Adolf Hitler:[46][47]

I swear to you, Adolf Hitler, as Germanic Führer loyalty and bravery. I pledge you and the superiors which you appointed obedience until death. So help me God.[49]

This title was assumed by Hitler on 23 June 1941, at the suggestion of Himmler.[49] On 12 December 1941 the Dutch right-wing nationalist Anton Mussert also addressed him in this fashion when he proclaimed his allegiance to Hitler during a visit to the Reich Chancellery in Berlin.[50] He had wanted to address Hitler as Führer aller Germanen ("Führer of all Germanics"), but Hitler personally decreed the former style.[49] Historian Loe de Jong speculates on the difference between the two: Führer aller Germanen implied a position separate from Hitler's role as Führer und Reichskanzler des Grossdeutschen Reiches ("Führer and Reich Chancellor of the Greater German Reich"), while germanischer Führer served more as an attribute of that main function.[50] As late as 1944 occasional propaganda publications continued to refer to him by this unofficial title as well however.[51] Mussert held that Hitler was predestined to become the Führer of Germanics because of his congruous personal history: Hitler originally was an Austrian national, who enlisted in the Bavarian army and lost his Austrian citizenship. He thus remained stateless for seven years, during which, according to Mussert, he was "the Germanic leader and nothing else".[52]

The Swastika Flag was to be used as a symbol to represent not only the National Socialist movement, but also the unity of the Nordic-Germanic peoples into a single state.[53] The swastika was seen by many National Socialists as a fundamentally Germanic and European symbol despite its presence among many cultures worldwide.

Hitler had long intended to architecturally reconstruct the German capital Berlin into a new imperial metropolis, which he decided in 1942 to rename Germania upon its scheduled completion in 1950. The name was specifically chosen to make it the clear central point of the envisioned Germanic empire, and to re-enforce the notion of a united Germanic-Nordic state upon the Germanic peoples of Europe.[54]

Just as the Bavarians and the Prussians had to be impressed by Bismarck of the German idea, so too must the Germanic peoples of continental Europe be steered towards the Germanic concept. He [Hitler] even considers it good that by renaming the Reich capital Berlin into 'Germania', we'll have given considerable driving force to this task. The name Germania for the Reich capital would be very appropriate, for in spite of how far removed those belonging to the Germanic racial core will be, this capital will instill a sense of unity.— Adolf Hitler, [55]

Policies undertaken in the countries

Low countries

| “ | For him [Hitler] it is self-evident [eine Selbstverständlichkeit] that Belgium and Flanders and Brabant will likewise be turned into German Reichsgaue (provinces). The Netherlands will also not be allowed to lead a politically independent life... Whether the Dutch offer any resistance to this or not, is fairly irrelevant. | ” |

| — Joseph Goebbels, [56] | ||

The German plans of annexation were more advanced for the Low Countries than for the Nordic states, due in part because of their closer geographical proximity as well as cultural, historical and ethnic ties to Germany. Luxembourg and Belgium were both formally annexed into the German Reich during World War II, in 1942 and 1944 respectively, the latter as the new Reichsgaue of Flandern and Wallonien (the proposed third one, Brabant, was not implemented in this arrangement) and a Brussels District. On April 5, 1942, while having dinner with an entourage including Heinrich Himmler, Hitler declared his intention that the Low Countries would be included whole into the Reich, at which point the Greater German Reich would be reformed into the Germanic Reich (simply "the Reich" in common parlance) to signify this change.[27]

In October 1940 Hitler disclosed to Benito Mussolini that he intended to leave the Netherlands semi-independent because he wanted that country to retain its overseas colonial empire after the war.[57] This factor was removed after the Japanese took over the Netherlands East Indies, the primary component of that domain.[57] The resulting German plans for the Netherlands suggested its transformation into a Gau Westland, which would eventually be further broken-up into five new Gaue or gewesten (historical Dutch term for a type of sub-national polity). Fritz Schmidt, a ranking German official in the occupied Netherlands who hoped to become the Gauleiter of this new province on Germany's western periphery stated that it could even be called Gau Holland, as long as the Wilhelmus (the Dutch national anthem) and similar patriotic symbols were to be forbidden.[58] Rotterdam, which had actually been largely destroyed in the course of the 1940 invasion was to be rebuilt as the most important port-city in the "Germanic area" due to its situation at the mouth of the Rhine river.[59]

Himmler's personal masseur Felix Kersten claimed that the former even contemplated resettling the entire Dutch population, some 8 million people in total at the time, to agricultural lands in the Vistula and Bug River valleys of German-occupied Poland as the most efficient way of facilitating their immediate Germanization.[60] In this eventuality he is alleged to have further hoped to establish an SS Province of Holland in vacated Dutch territory, and to distribute all confiscated Dutch property and real estate among reliable SS-men.[61] However this claim was shown to be a myth by Loe de Jong in his book Two Legends of the Third Reich.[62]

The position in the future empire of the Frisians, another Germanic people, was discussed on 5 April 1942 in one of Hitler’s many wartime dinner-conversations.[27] Himmler commented that there was ostensibly no real sense of community between the different indigenous ethnic groups in the Netherlands. He then stated that the Dutch Frisians in particular seemed to hold no affection for being part of a nation-state based on the Dutch national identity, and felt a much greater sense of kinship with their German Frisian brethren across the Ems River in East Frisia, an observation Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel agreed with based on his own experiences.[27] Hitler determined that the best course of action in that case would be to unite the two Frisian regions on both sides of the border into a single province, and would at a later point in time further discuss the topic with Arthur Seyss-Inquart, the governor of the German regime in the Netherlands.[27] By late May of that year these discussions were apparently concluded, as on the 29th he pledged that he would not allow the West-Frisians to remain part of Holland, and that since they were "part of the exact same race as the people of East Frisia" had to be joined into one province.[63]

Hitler considered Wallonia to be "in reality German lands" which were gradually detached from the Germanic territories by the French Romanization of the Walloons, and that Germany thus had "every right" to take these back.[12] Before the decision was made to include Wallonia in its entirety, several smaller areas straddling the traditional Germanic-Romance language border in Western Europe were already considered for inclusion. These included the small Lëtzebuergesh-speaking area centred on Arlon,[64] as well as the Low Dietsch-speaking region west of Eupen (the so-called Platdietse Streek) around the city of Limbourg, historical capital of the Duchy of Limburg.[65]

Scandinavia

After their invasion in Operation Weserübung, Hitler vowed that he would never again leave Norway,[59] and favored annexing Denmark as a German province even more due to its small size and relative closeness to Germany.[66] Himmler's hopes were an expansion of the project so that Iceland would also be included among the group of Germanic countries which would have to be gradually incorporated into the Reich.[66] He was also among the group of more esoteric National Socialists who believed either Iceland or Greenland to be the mystical land of Thule, a purported original homeland of the ancient Aryan race.[67] From a military point of view, the Kriegsmarine command hoped to see the Spitsbergen, Iceland, Greenland, the Faroe Isles and possibly the Shetland Isles (which were also claimed by the Quisling regime[68]) under its domination to guarantee German naval access to the mid-Atlantic.[69]

There was preparation for the construction of a new German metropolis of 300.000 inhabitants called Nordstern ("North Star") next to the Norwegian city of Trondheim. It would be accompanied by a new naval base that was intended to be the Germany's largest.[59][70] This city was to be connected to Germany proper by an Autobahn across the Little and Great Belts. It would also house an art museum for the northern part of the Germanic empire, housing "only works of German artists."[71]

Sweden's future subordination into the 'New Order' was considered by the regime.[72] Himmler stated that the Swedes were the "epitome of the Nordic spirit and the Nordic man", and looked forward to incorporating central and southern Sweden to the Germanic Empire.[72] Himmler offered northern Sweden, with its Finnish minority, to Finland, along with the Norwegian port of Kirkenes, although this suggestion was rejected by Finnish Foreign Minister Witting.[73][74] Felix Kersten, claimed that Himmler had expressed regret that Germany had not occupied Sweden during Operation Weserübung, but was certain that this error was to be rectified after the war.[75] In April 1942, Goebbels expressed similar views in his diary, writing that Germany should have occupied the country during its campaign in the north, as "this state has no right to national existence anyway".[76] In 1940, Hermann Göring suggested that Sweden's future position in the Reich was similar to that of Bavaria in the German Empire.[72] The ethnically Swedish Åland Islands, which were awarded to Finland by the League of Nations in 1921, were likely to join Sweden in the Germanic Empire. In the spring of 1941, the German military attaché in Helsinki reported to his Swedish counterpart that Germany would need transit rights through Sweden for the imminent invasion of the Soviet Union, and in the case of finding her cooperative would permit the Swedish annexation of the islands.[77] Hitler did veto the idea of a complete union between the two states of Sweden and Finland, however.[78]

Despite the majority of its people being of Finno-Ugric origin, Finland was given the status of being an "honorary Nordic nation" (from a National Socialist racial perspective, not a national one) by Hitler as reward for its military importance in the ongoing conflict against the Soviet Union.[78] The Swedish-speaking minority of the country, who in 1941 comprised 9.6% of the total population, were considered Nordic and were initially preferred over Finnish speakers in recruitment for the Finnish Volunteer Battalion of the Waffen-SS.[79] Finland's Nordic status did not mean however that it was intended to be absorbed into the Germanic Empire, but instead expected to become the guardian of Germany’s northern flank against the hostile remnants of a conquered USSR by attaining control over Karelian territory, occupied by the Finns in 1941.[78] Hitler also considered the Finnish and Karelian climates unsuitable for German colonization.[80] Even so, the possibility of Finland's eventual inclusion as a federated state in the empire as a long-term objective was mulled over by Hitler in 1941, but by 1942 he seems to have abandoned this line of thinking.[80] According to Kersten, as Finland signed an armistice with the Soviet Union and broke off diplomatic relations with her former brother-in-arms Germany in September 1944, Himmler felt remorse for not eliminating the Finnish state, government and its "masonic" leadership sooner, and transforming the country into a "National Socialist Finland with a Germanic outlook".[81]

Switzerland

The same implicit hostility toward neutral nations such as Sweden was also held towards Switzerland. Goebbels noted in his diary on December 18, 1941, that "It would be a veritable insult to God if they [the neutrals] would not only survive this war unscathed while the major powers make such great sacrifices, but also profit from it. We will certainly make sure that this will not happen."[82]

The Swiss people were seen by Nazi ideologists as a mere offshoot of the German nation, although one led astray by decadent Western ideals of democracy and materialism.[83] Hitler decried the Swiss as "a misbegotten branch of our Volk" and the Swiss state as "a pimple on the face of Europe" deeming them unsuitable for settling the territories that the Nazis expected to colonize in Eastern Europe.[84]

Himmler discussed plans with his subordinates to integrate at least the German-speaking parts of Switzerland completely with the rest of Germany, and had several persons in mind for the post of a Reichskommissar for the 're-union' of Switzerland with the German Reich (in analogy to the office that Josef Bürckel held after Austria's absorption into Germany during the Anschluss). Later this official was to subsequently become the new Reichsstatthalter of the area after completing its total assimilation.[10][85] In August 1940, Gauleiter of Westfalen-South Josef Wagner and the Minister President of Baden Walter Köhler spoke in favor of the amalgamation of Switzerland to Reichsgau Burgund (see below) and suggested that the seat of government for this new administrative territory should be the dormant Palais des Nations in Geneva.[86]

Operation Tannenbaum, a military offensive intended to occupy all of Switzerland, most likely in co-operation with Italy (which itself desired the Italian-speaking areas of Switzerland), was in the planning stages during 1940-1941. Its implementation was seriously considered by the German military after the armistice with France, but it was definitively shelved after the start of Operation Barbarossa had directed the attention of the Wehrmacht elsewhere.[87]

Eastern France

.png)

In the aftermath of the Munich Agreement, Hitler and French Prime Minister Édouard Daladier in December 1938 made an agreement that officially declared that Germany was relinquishing its previous territorial claims on Alsace-Lorraine in the interest of maintaining peaceful relations between France and Germany and both pledged to be involved in mutual consultation on matters involving the interests of both countries.[88] However at the same time Hitler in private advised the High Command of the Wehrmacht to prepare operational plans for a joint German–Italian war against France.[88]

Under the auspices of State Secretary Wilhelm Stuckart the Reich Interior Ministry produced an initial memo for the planned annexation of a strip of eastern France in June 1940, stretching from the mouth of the Somme to Lake Geneva,[89] and on July 10, 1940, Himmler toured the region to inspect its Germanization potential.[32] According to documents produced in December 1940, the annexed territory would consist of nine French departments, and the Germanization action would require the settlement of a million Germans from "peasant families".[32] Himmler decided that South Tyrolean emigrants (see South Tyrol Option Agreement) would be used as settlers, and the towns of the region would receive South Tyrolean place-names such as Bozen, Brixen, Meran, and so on.[90] By 1942 Hitler had, however, decided that the South Tyroleans would be instead used to settle the Crimea, and Himmler regretfully noted "For Burgundy, we will just have to find another [Germanic] ethnic group."[91]

Hitler claimed French territory even beyond the historical border of the Holy Roman Empire. He stated that in order to ensure German hegemony on the continent, Germany must "also retain military strong points on what was formerly the French Atlantic coast" and emphasized that "nothing on earth would persuade us to abandon such safe positions as those on the Channel coast, captured during the campaign in France and consolidated by the Organisation Todt."[92] Several major French cities along the coast were given the designation Festung ("fortress"; "stronghold") by Hitler, such as Le Havre, Brest and St. Nazaire,[93] suggesting that they were to remain under permanent post-war German administration.

However the war ends, France will have to pay dearly, for she caused and started it. She is now being thrown back to her borders of AD 1500. This means that Burgundy will again become part of the Reich. We shall thereby win a province that so far as beauty and wealth are concerned compares more than favorably with any other German province.— Joseph Goebbels, 26 April 1942, [94]

Atlantic islands

During the summer of 1940, Hitler considered the possibility of occupying the Portuguese Azores, Cape Verde and Madeira and the Spanish Canary islands to deny the British a staging ground for military actions against Nazi-controlled Europe.[25][95] In September 1940, Hitler further raised the issue in a discussion with the Spanish Foreign Minister Serrano Súñer, offering now Spain to transfer one of the Canary islands to German usage for the price of French Morocco.[95] Although Hitler's interest in the Atlantic islands must be understood from a framework imposed by the military situation of 1940, he ultimately had no plans of ever releasing these important naval bases from German control.[95]

It had been alleged by Canadian historian Holger Herwig that both in November 1940 and May 1941, leading into and through to the period in which Japan began planning the naval attack that would bring the United States into the war,[96] that Hitler had stated that he had a desire to "deploy long-range bombers against American cities from the Azores." Due to their location, Hitler seemed to think that a Luftwaffe airbase located on the Portuguese Azores islands were Germany's "only possibility of carrying out aerial attacks from a land base against the United States", in a period about a year before the May 1942 emergence of the Amerika Bomber trans-oceanic range strategic bomber design competition.[97]

Poland

Relations between Germany and Poland altered from the early to the late 1930s. While Hitler and Nazi party before taking power openly talked about destroying Poland and were hostile to Poles, after gaining power until February 1939 Hitler tried to conceal his true intentions towards Poland and revealed them only to his closest associates; the signing of non-aggression pact with Poland in 1934 was a political maneuver to conceal his true intentions towards Poland.[6] The German Reich publicly claimed to seek rapproachment with Poland to avoid Poland entering the Soviet sphere of influence, and appealed to anti-Soviet sentiment in Poland.[98] The Soviet Union in turn at this time competed with Germany for influence in Poland.[98] In 1934 Poland reached several agreements with Germany. One was an agreement on the treatment of minorities in both countries.[99] The other was a non-aggression pact in which both countries agreed to peaceful settlement of disputes, including that over territory; the agreement however still regarded the two countries as not having settled their borders.[7] At this time, Germany sought to convince Poland that it would allow for Polish existence should Germany invade the Soviet Union resulting in Germany taking lebensraum from the Soviet Union, by offering Poland the right to annex the entirety of Ukraine from the Soviet Union while Germany would annex other Soviet territories.[7] In 1937, Germany condemned Poland for violating the minorities agreement, but publicly proposed that it would accept a resolution whereby Germany would reciprocally accept the Polish demand for Germany abandon assimilation of Polish minorities if Poland upheld its agreement to abandon assimilation of Germans.[99]

Germany's proposal was met with resistance in Poland, particularly by the Polish Western Union (PZZ) and the opposition party National Democratic party, with Poland only agreeing to a watered down version of the Joint Declaration on Minorities, on 5 November 1937.[99] Hitler welcomed this agreement and meet with representatives of Polish government and representatives of Polish minority in Germany, but in secret was frustrated and held a meeting where he declared to prepare Germany for a war to destroy Poland.[99] However, later in December 1938, Hitler indicated to his confidants that he was still interested in utilizing Poland in a war against the Soviet Union, claiming that Polish soldiers fighting alongside Germany against the Soviet Union would be beneficial in that it would reduce the need for German manpower in the fighting.[7] At the same time Nazi Germany has been secretly preparing German minority in Poland for war and since 1935 weapons were being smuggled and gathered in frontier Polish regions by Nazi intelligence, and spying networks established.[100] In November 1938, Nazi Germany organized German paramilitary units in Polish Pomerania that were to engage in diversion, sabotage as well as murder and ethnic cleansing upon German invasion of Poland.[100] At the end of 1938 one of the first editions of Sonderfahndungsbuch Polen was printed by the Nazis, containing several thousand names of Poles targeted for execution and imprisonment after invasion of Poland.[101] In January 1939, Ribbentrop held negotiations with Józef Beck, the Polish minister of foreign affairs; and Edward Rydz-Śmigły, the commander-in-chief of the Polish Army; in which Ribbentrop urged them to have Poland enter the Anti-Comintern Pact under German hegemony for expansion eastward, whereby Germany offered Poland territories in Slovakia and Ukraine.[7]

Ribbentrop in private discussion with German officials stated that he hoped that by offering Poland territories in the Soviet Union, that Germany would gain not only from Polish cooperation in a war with the Soviet Union, but also that Poland would surrender Polish Corridor to Germany in exchange for these gains, because though it would lose access to the Baltic Sea, it would gain access to the Black Sea via Ukraine.[7] However Beck refused German demands to annex territory inhabited by majority of Poles and connecting majority of Polish exports and imports with the outside world and was shocked at the idea of a war with the Soviet Union.[7] Polish administration saw the plan as a threat to Polish sovereignty, practically subordinating Poland to the Axis and the Anti-Comintern Bloc while reducing the country to a state of near-servitude as its entire trade would be dependent on Germany.[102] With the aftermath of the German occupation of Czechoslovakia and creation of a German client state of Slovakia, the German government believed that Poland would yield to German demands, however it did not.[7] In private, Hitler revealed in May that Danzig was not the real issue to him, but pursuit of Lebensraum for Germany.[7]

Role of Britain

United Kingdom

.jpg)

The one Germanic-language speaking country that was not included in the Pan-Germanic unification aim was the United Kingdom,[103] in spite of its near-universal acceptance by the Nazi government as being part of the Germanic world.[104] Leading Nordic ideologist Hans F. K. Günther theorized that the Anglo-Saxons had been more successful than the Germans in maintaining racial purity and that the coastal and island areas of Scotland, Ireland, Cornwall and Wales had received additional Nordic blood through Norse raids and colonization during the Viking Age, and the Anglo-Saxons of East Anglia and Northern England had been under Danish rule in the 9th and 10th centuries.[105] Günther referred to this historical process as Aufnordung ("additional nordification"), which finally culminated in the Norman conquest of England in 1066.[105] Britain was thus a nation created by struggle and the survival of the fittest among the various Aryan peoples of the isles, and was able to pursue global conquest and empire-building because of its superior racial heredity born through this development.[106]

Hitler professed an admiration for the imperial might of the British Empire in Zweites Buch as proof of the racial superiority of the Aryan race,[107] hoping that Germany would emulate British "ruthlessness" and "absence of moral scruples" in establishing its own colonial empire in Eastern Europe.[108] One of his primary foreign policy aims throughout the 1930s was to establish a military alliance with both the English (Hitler conflated England with Britain and the United Kingdom in his writings and speeches) as well as the Italians to neutralize France as a strategic threat to German security for eastward expansion.

When it became apparent to the National Socialist leadership that the United Kingdom was not interested in a military alliance, anti-British policies were adopted to ensure the attainment of Germany’s war aims. Even during the war however, hope remained that Britain would in time yet become a reliable German ally.[109] Hitler preferred to see the British Empire preserved as a world power, because its break-up would benefit other countries far more than it would Germany, particularly the United States and Japan.[109] In fact, Hitler's strategy during 1935-1937 for winning Britain over was based on a German guarantee of defence of the British Empire.[110] After the war, Ribbentrop testified that in 1935 Hitler had promised to deliver twelve German divisions to the disposal of Britain for maintaining the integrity of her colonial possessions.[111]

The continued military actions against Britain after the fall of France had the strategic goal of making Britain 'see the light' and conduct an armistice with the Axis powers, with July 1, 1940, being named by the Germans as the "probable date" for the cessation of hostilities.[112] On May 21, 1940, Franz Halder, the head of the Army General Staff, after a consultation with Hitler concerning the aims envisaged by the Führer during the present war, wrote in his diary: "We are seeking contact with Britain on the basis of partitioning the world".[113]

One of Hitler's sub-goals for the invasion of Russia was to win over Britain to the German side. He believed that after the military collapse of the USSR, "within a few weeks" Britain would be forced either into a surrender or else come to join Germany as a "junior partner" in the Axis.[114] Britain's role in this alliance was reserved to support German naval and aerial military actions against the USA in a fight for world supremacy conducted from the Axis power bases of Europe, Africa and the Atlantic.[115] On August 8, 1941, Hitler stated that he looked forward to the eventual day when "England and Germany [march] together against America" and on January 7, 1942, he daydreamed that it was "not impossible" for Britain to quit the war and join the Axis side, leading to a situation where "it will be a German-British army that will chase the Americans from Iceland".[116] National Socialist ideologist Alfred Rosenberg hoped that after the victorious conclusion of the war against the USSR, Englishmen, along with other Germanic nationalities, would join the German settlers in colonizing the conquered eastern territories.[23]

From a historical perspective Britain’s situation was likened to that which the Austrian Empire found itself in after it was defeated by the Kingdom of Prussia in the Battle of Königgrätz in 1866.[109] As Austria was thereafter formally excluded from German affairs, so too would Britain be excluded from continental affairs in the event of a German victory. Yet afterwards, Austria-Hungary became a loyal ally of the German Empire in the pre-World War I power alignments in Europe, and it was hoped that Britain would come to fulfill this same role.[109]

Channel Islands

The British Channel Islands were to be permanently integrated into the Germanic Empire.[117] On July 22, 1940, Hitler stated that after the war, the islands were to be given to the control of Robert Ley's German Labour Front, and transferred into Strength Through Joy holiday resorts.[118] German scholar Karl Heinz Pfeffer toured the islands in 1941, and recommended that the German occupiers should appeal to the islanders' Norman heritage and treat the islands as "Germanic micro-states", whose union with Britain was only an accident of history.[119] He likened the preferred policy concerning the islands similar to the one pursued by the British in Malta, where the Maltese language had been "artificially" supported against the Italian language.[119]

Ireland

A military operation plan for the invasion of Ireland in support of Operation Sea Lion was drawn up by the Germans in August 1940. Occupied Ireland was to be ruled along with Britain in a temporary administrative system divided into six military-economic commands, with one of the headquarters being situated in Dublin.[120] Ireland's future position in the New Order is unclear, but it is known that Hitler would have united Ulster with the Irish state.[121]

Role of Northern Italy

.svg.png)

Hitler regarded northern Italians to be strongly Aryan[122] but not southern Italians.[123] He even admitted that The Ahnenerbe, an archaeological organization associated with the SS, asserted that archaeological evidence proved the presence of Nordic-Germanic peoples in the region of South Tyrol in the Neolithic era that it claimed proved the significance of ancient Nordic-Germanic influence on northern Italy.[124] The NSDAP regime regarded the ancient Romans to have been largely a people of the Mediterranean race however they claimed that the Roman ruling classes were Nordic, descended from Aryan conquerors from the North; and that this Nordic Aryan minority was responsible for the rise of Roman civilization.[125] The National Socialists viewed the downfall of the Roman Empire as being the result of the deterioration of the purity of the Nordic Aryan ruling class through its intermixing with the inferior Mediterranean types that led to the empire's decay.[125] In addition, racial intermixing in the population in general was also blamed for Rome's downfall, claiming that Italians were a hybrid of races, including black African races. Due to the darker complexion of Mediterranean peoples, Hitler regarded them as having traces of Negroid blood and therefore did not have strong Nordic Aryan heritage and were thus inferior to those that had stronger Nordic heritage.[126] Hitler held immense admiration for the Roman Empire and its legacy.[127] Hitler praised post-Roman era achievements of northern Italians such as Sandro Botticelli, Michelangelo, Dante Alighieri, and Benito Mussolini.[128] The Nazis ascribed the great achievements of post-Roman era northern Italians to the presence of Nordic racial heritage in such people who via their Nordic heritage had Germanic ancestors, such as NSDAP Foreign Affairs official Alfred Rosenberg recognizing Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci as exemplary Nordic men of history.[129] German official Hermann Hartmann wrote that Italian scientist Galileo Galilei was clearly Nordic with deep Germanic roots because of his blond hair, blue eyes, and long face.[129] The Nazis claimed that aside from biologically Nordic people that a Nordic soul could inhabit a non-Nordic body.[130] Hitler emphasized the role of Germanic influence in Northern Italy, such as stating that the art of Northern Italy was "nothing but pure German",[131] and National Socialist scholars viewed that the Ladin and Friulian minorities of Northern Italy were racially, historically and culturally a part of the Germanic world.[132] To put it bluntly, Hitler declared in private talks that the modern Reich should emulate the racial policy of the old Roman-Germanic Holy Empire, by annexing the Italian lands and especially Lombardy, whose population had well preserved their original Germanic Aryan character, unlike the lands of East Europe, with its racially alien population, scarcely marked by a Germanic contribution.[133] According to him, German are more closely linked with the Italians than with any other people.[131] Plans to incorporate northern Italy into the Greater Germanic Reich were influenced by the collapse of the fascist Italian government in 1943.

"From the cultural point of view, we are more closely linked with the Italians than with any other people. The art of Northern Italy is something we have in common with them: nothing but pure Germans. The objectionable Italian type is found only in the South, and not everywhere even there. We also have this type in our own country. When I think of them: Vienna-Ottakring, Munich-Giesing, Berlin-Pankow ! If I compare the two types, that of these degenerate Italians and our type, I find it very difficult to say which of the two is the more antipathetic."

The Nazi regime's stances in regards to northern Italy was influenced by the regime's relations with the Italian government, and particularly Mussolini's Fascist regime. Hitler deeply admired and emulated Mussolini. Hitler emphasized the racial closeness of his ally Mussolini to Germans of Alpine racial heritage.[134] Hitler regarded Mussolini to not be seriously contaminated by the blood of the Mediterranean race.[128] Other National Socialists had negative views of Mussolini and the Fascist regime. The NSDAP's first leader, Anton Drexler was one of the most extreme in his negative views of Mussolini – claiming that Mussolini was "probably" a Jew and that Fascism was a Jewish movement.[135] In addition there was a perception in Germany of Italians being racially weak, feckless, corrupt and corrupting, bad soldiers as perceived as demonstrated at the Battle of Caporetto in World War I, for being part of the powers that established the Treaty of Versailles, and for being a treacherous people given Italy's abandonment of the Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary in World War I to join the Entente.[135] Hitler responded to the review of Italy betraying Germany and Austria-Hungary in World War I by saying that this was a consequence of Imperial Germany's decision to focus its attention on upholding the moribund Austro-Hungarian empire while ignoring and disregarding the more promising Italy.[135]

The region of South Tyrol had been a place of contending claims and conflict between German nationalism and Italian nationalism. One of the leading founders of Italian nationalism, Giuseppe Mazzini, along with Ettore Tolomei, claimed that the German-speaking South Tyrolian population were in fact mostly a Germanicized population of Roman origin who needed to be "liberated and returned to their rightful culture".[136] With the defeat of Austria-Hungary in World War I, the peace treaty designated to Italy the South Tyrol, with its border with Austria along the Brenner Pass.[136] The Italian Fascist regime pursued Italianization of South Tyrol, by restricting use of the German language while promoting the Italian language; promoting mass migration of Italians into the region, encouraged mainly through industrialization; and resettlement of the German-speaking population.[137]

After Mussolini had made clear in 1922 that he would never give up the region of South Tyrol from being in Italy, Hitler adopted this position.[138] Hitler in Mein Kampf had declared that concerns over the rights of Germans in South Tyrol under Italian sovereignty was a non-issue considering the advantages that would be gained from a German-Italian alliance with Mussolini's Fascist regime.[139] In Mein Kampf Hitler also made clear that he was opposed to having a war with Italy for the sake of obtaining South Tyrol.[138] This position by Hitler of abandoning German land claims to South Tyrol produced aggravation among some NSDAP members who up to the late 1920s found it difficult to accept the position.[140]

On 7 May 1938, Hitler during a public visit to Rome declared his commitment to the existing border between Germany (that included Austria upon the Anschluss) and Italy at the Brenner Pass.[141]

In 1939, Hitler and Mussolini resolved the problem of self-determination of Germans and maintaining the Brenner Pass frontier by an agreement in which German South Tyroleans were given the choice of either assimilation into Italian culture, or leave South Tyrol for Germany; most opted to leave for Germany.[141]

After King Victor Emmanuel III of the Kingdom of Italy removed Mussolini from power, Hitler on 28 July 1943 was preparing for the expected abandonment of the Axis for the Allies by the Kingdom of Italy's new government, and was preparing to exact retribution for the expected betrayal by planning to partition Italy.[142] In particular Hitler was considering the creation of a "Lombard State" in northern Italy that would be incorporated into the Greater Germanic Reich, while South Tyrol and Venice would be annexed directly into Germany.[142]

In the aftermath of the Kingdom of Italy's abandonment of the Axis on 8 September 1943, Germany seized and de facto incorporated Italian territories into its direct control.[143]

After the Kingdom of Italy capitulated to the Allies in September 1943, according to Goebbels in his personal diary on 29 September 1943, wrote that Hitler had expressed that the Italian-German border should extend to those of the region of Veneto.[144] Veneto was to be included into the Reich in an "autonomous form", and to benefit from the post-war influx of German tourists.[144] At the time when Italy was on the verge of declaring an armistice with the Allies, Himmler declared to Felix Kersten that Northern Italy, along with the Italian-speaking part of Switzerland, was "bound to eventually be included in Greater Germany anyway".[145]

Whatever was once an Austrian possession we must get back into our own hands. The Italians by their infidelity and treachery have lost any claim to a national state of the modern type.

After the rescue of Mussolini and the establishment of the Italian Social Republic (RSI), in spite of urging by local German officials, Hitler refused to officially annex South Tyrol, instead he decided that the RSI should hold official sovereignty over these territories, and forbade all measures that would give the impression of official annexation of South Tyrol.[147] However, in practice the territory of South Tyrol within the boundaries defined by Germany as Operationszone Alpenvorland that included Trent, Bolzano, and Belluno, were de facto incorporated into Germany's Reichsgau Tirol-Vorarlberg and administered by its Gauleiter Franz Hofer.[143][148] While the region identified by Germany as Operationszone Adriatisches Küstenland that included Udine, Gorizia, Trieste, Pola, Fiume (Rijeka), and Ljubljana were de facto incorporated into Reichsgau Kärnten and administered by its Gauleiter Friedrich Rainer.[149]

In a supplementary OKW order dated 10 September 1943, Hitler decrees on the establishment of further Operational Zones in Northern Italy, which were the stretch all the way to the French border.[150] Unlike Alpenvorland and Küstenland, these zones did not immediately receive high commissioners (oberster kommissar) as civilian advisors, but were military regions where the commander was to exercise power on behalf of Army Group B.[150] Operation zone Nordwest-Alpen or Schweizer Grenze was located between the Stelvio Pass and Monte Rosa and was to contain wholly the Italian provinces of Sondrio and Como and parts of the provinces of Brescia, Varese, Novara and Vercelli.[151] The zone of Französische Grenze was to encompass areas west of Monte Rosa and was to incorporate the province of Aosta and a part of the province of Turin, and presumably also the provinces of Cuneo and Imperia.[151]

From Autumn 1943 onward, members of the Ahnenerbe, associated with the SS, asserted that archaeological evidence of ancient farmsteads and architecture proved the presence of Nordic-Germanic peoples in the region of South Tyrol in the Neolithic era including prototypical Lombard style architecture, the significance of ancient Nordic-Germanic influence on Italy, and most importantly that South Tyrol by its past and present and historic racial and cultural circumstances, was "Nordic-Germanic national soil".[124]

Expected participation in the colonization of Eastern Europe

Despite the pursued aim of pan-Germanic unification, the primary goal of the German Reich’s territorial expansionism was to acquire sufficient Lebensraum (living space) in Eastern Europe for the Germanic übermenschen or superior men. The primary objective of this aim was to transform Germany into a complete economic autarky, the end-result of which would be a state of continent-wide German hegemony over Europe. This was to be accomplished through the enlargement of the territorial base of the German state and the expansion of the German population,[152] and the wholesale extermination of the indigenous Slavic inhabitants and the Germanisation of Baltic inhabitants.[153]

[on German colonization of Russia] As for the two or three million men whom we need to accomplish this task, we will find them more quickly than we think. They will come from Germany, Scandinavia, the western countries, and America. I shall no longer be here to see all that, but in twenty years the Ukraine will already be a home for twenty million inhabitants besides the natives.— Adolf Hitler, [154]

Because of their perceived racial worth, the NSDAP leadership was enthusiastic at the prospect of "recruiting" people from the Germanic countries to also settle these territories after the Slavic inhabitants would have been driven out.[155] The racial planners were partly motivated in this because studies indicated that Germany would likely not be able to recruit enough colonial settlers for the eastern territories from its own country and other Germanic groups would therefore be required.[153] Hitler insisted however that German settlers would have to dominate the newly colonized areas.[17] Himmler's original plan for the Hegewald settlement was to settle Dutch and Scandinavians there in addition to Germans, which was unsuccessful.[156]

Later development

As the foreign volunteers of the Waffen-SS were increasingly of non-Germanic origin, especially after the Battle of Stalingrad, among the organization's leadership (e.g. Felix Steiner) the proposition for a Greater Germanic Empire gave way to a concept of a European union of self-governing states, unified by German hegemony and the common enemy of Bolshevism.[157] The Waffen-SS was to be the eventual nucleus of a common European army where each state would be represented by a national contingent.[157] Himmler himself, however, gave no concession to these views, and held on to his Pan-Germanic vision in a speech given in April 1943 to the officers of SS divisions LSAH, Das Reich and Totenkopf:

We do not expect you to renounce your nation. [...] We do not expect you to become German out of opportunism. We do expect you to subordinate your national ideal to a greater racial and historical ideal, to the Germanic Reich.[157]

See also

- Administrative divisions of Nazi Germany

- Areas annexed by Nazi Germany

- Empire of Japan

- Fourth Reich

- Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere

- Hitler's plans for North America

- Hypothetical Axis victory in World War II

- Imperial Italy

- Italian Empire

- Kleindeutschland and Grossdeutschland

- Latin Bloc (proposed alliance)

- New Order (Nazism), Nazi concept for a post-World War II world order

- Pan movements

- Racial policy of Nazi Germany

Notes

- ↑ This passage should in all likelihood be interpreted to mean "extending up to northern Italy", not that it would also include this region. There is no convincing evidence that Hitler intended to include any Italian provinces in the German state before 1943, including South Tyrol.

References

- ↑ "Utopia: The 'Greater Germanic Reich of the German Nation'". München – Berlin: Institut für Zeitgeschichte. 1999.

- 1 2 Elvert 1999, p. 325.

- ↑ Speer 1970, p. 260.

- ↑ DHM – Mein Kampf

- ↑ Majer, Diemut (2003). "Non-Germans" under the Third Reich: the Nazi judicial and administrative system in Germany and occupied Eastern Europe with special regard to occupied Poland, 1939—1945. JHU Press. pp. 188–9. ISBN 0-8018-6493-3.

- 1 2 Stutthof. Zeszyty Muzeum, 3. PL ISSN 0137-5377. Mirosław Gliński Geneza obozu koncentracyjnego Stutthof na tle hitlerowskich przygotowan w Gdansku do wojny z Polsk

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Oscar Pinkus. The War Aims and Strategies of Adolf Hitler. McFarland, 2005. p. 44.

- ↑ Gerhard L. Weinberg. Hitler's Foreign Policy 1933-1939: The Road to World War II. Enigma Books, 2013. p. 152.

- ↑ Heinrich August Winkler. Germany, The Long Road West, 1933-1990. Oxford, England, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 74.

- 1 2 Rich 1974, pp. 401–402.

- ↑ Strobl 2000, pp. 202–208.

- 1 2 Williams 2005, p. 209.

- ↑ André Mineau. Operation Barbarossa: Ideology and Ethics Against Human Dignity. Rodopi, 2004. p. 36

- ↑ Rolf Dieter Müller, Gerd R. Ueberschär. Hitler's War in the East, 1941-1945: A Critical Assessment. Berghahn Books, 2009. p. 89.

- ↑ Bradl Lightbody. The Second World War: Ambitions to Nemesis. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2004. p. 97.

- 1 2 3 Bohn 1997, p. 7.

- 1 2 Wright 1968, p. 115.

- ↑ Hitler 2000, p. 225.

- ↑ Housden 2000 , p. 163.

- ↑ Grafton et al 2010, p. 363.

- ↑ Hitler, Pol Pot, and Hutu Power: Distinguishing Themes of Genocidal Ideology Professor Ben Kiernan, Holocaust and the United Nations Discussion Paper

- ↑ Hitler 2000, p. 307.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fest 1973, p. 685.

- ↑ Hitler 1927, p. 1.

- 1 2 Fest 1973, p. 210.

- ↑ Fink 1985, pp. 27, 152.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hitler 2000, p. 306.

- 1 2 3 Hattstein 2006, p. 321.

- ↑ Hamann, Brigitte (1999). Hitler's Vienna: A Dictator's Apprenticeship. Trans. Thomas Thornton. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512537-5.

- ↑ Haman 1999, p. 110

- 1 2 3 Brockmann 2006, p. 179.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sager & Winkler 2007, p. 74.

- ↑ Goebbels, p. 51.

- 1 2 3 Wright 1968, pp. 141–142.

- ↑ Rothwell 2005, p. 31.

- ↑ Lipgens 1985, p. 41.

- 1 2 Speer 1970, pp. 147–148.

- 1 2 Domarus 2007, p. 158.

- 1 2 3 Speer 1970, pp. 115–116.

- ↑ Rich 1974, p. 318.

- 1 2 Welch 1983, p. 145.

- ↑ Rich 1974, pp. 24–25, 140.

- ↑ See e.g. Warmbrunn 1963, pp. 91–93.

- ↑ Rich 1974, p. 140.

- 1 2 Speer 1976, p. 47.

- 1 2 3 4 Bramstedt 2003, pp. 92–93.

- 1 2 Kroener, Müller & Umbreit 2003, pp. 122–123.

- ↑ Morgan 2003, p. 182.

- 1 2 3 De Jong 1974, p. 181.

- 1 2 De Jong 1974, pp. 199–200.

- ↑ Adolf Hitler: Führer aller Germanen. Storm, 1944.

- ↑ Lipgens 1985, p. 101

- ↑ Rich 1974, p. 26.

- ↑ Hitler 2000, p. 400

- ↑ Hillgruber & Picker, p. 182.

- ↑ Unpublished fragment from Joseph Goebbels' diaries, located in the collection of the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace, Palo Alto, California.

- 1 2 Rich 1974, p. 469, note 110.

- ↑ De Jong 1969, Vol. 1, p. 97.

- 1 2 3 Fest 1973, p. 689.

- ↑ Waller 2002, p. 20.

- ↑ Kersten 1947, pp. 84–85.

- ↑ Louis de Jong, 1972, reprinted in German translation: H-H. Wilhelm and L. de Jong. Zwei Legenden aus dem dritten Reich : quellenkritische Studien, Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt 1974, pp 79-142.

- ↑ Hitler (2000), 29th of May 1942.

- ↑ Gildea, Wieviorka & Warring 2006, p. 130.

- ↑ Hamacher, Hertz & Keenan 1989, p. 444.

- 1 2 Rothwell 2005, p. 32.

- ↑ Janssens 2005, p. 205.

- ↑ Philip H. Buss, Andrew Mollo (1978). Hitler's Germanic legions: an illustrated history of the Western European Legions with the SS, 1941-1943. Macdonald and Jane's, p. 89

- ↑ Stegemann & Vogel 1995, p. 286

- ↑ Weinberg 2006, pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Weinberg 2005, pp. 26–27.

- 1 2 3 Leitz 2000, p. 52.

- ↑ Ackermann 1970, p. 191.

- ↑ Kersten 1957, p. 143.

- ↑ Rich 1974, p. 500.

- ↑ The Goebbels diaries, 1942-1943, p.171.

- ↑ Griffiths 2004, pp. 180–181.

- 1 2 3 Rich 1974, p. 401.

- ↑ Nieme, Jarto; Pipes, Jason. "Finnish Volunteers in the Wehrmacht in WWII". Feldgrau. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- 1 2 Boog 2001, p. 922.

- ↑ Kersten 1947, pp. 131, 247.

- ↑ Urner 2002, p. x.

- ↑ Halbrook 1998, pp. 24–25.

- ↑ Hitler 2000.

- ↑ Fink 1985, pp. 71–72.

- ↑ Hans Rudolf Fuhrer (1982). Spionage gegen die Schweiz. Huber. p. 68. ISBN 3-274-00003-5.

- ↑ Halbrook 1998, p. 151.

- 1 2 Nazi Foreign Policy, 1933–1941: The Road to Global War. p. 58.

- ↑ Schöttler 2003, pp. 83–131.

- ↑ Steininger 2003, p. 67.

- ↑ Rich 1974, p. 384.

- ↑ Rich 1974, p. 198.

- ↑ Zaloga 2007, p. 10.

- ↑ The Goebbels diaries, 1942–1943, p. 189.

- 1 2 3 Stegemann & Vogel 1995, p. 211.

- ↑ Gailey, Harry A. (1997). War in the Pacific: From Pearl Harbor to Tokyo Bay. Presidio. p. 68. ISBN 0-89141-616-1.

- ↑ Duffy, James P. Target America: "Hitler's Plan to Attack the United States". The Lyons Press, 2006. ISBN 978-1-59228-934-9.

- 1 2 Jan Karski. The Great Powers and Poland: From Versailles to Yalta. Rowman & Littlefield, 2014. p. 197.

- 1 2 3 4 Richard Blanke. Orphans of Versailles: The Germans in Western Poland, 1918–1939. Lexington, Kentucky, USA: University Press of Kentucky, 1993. p. 215.

- 1 2 Stutthof: hitlerowski obóz koncentracyjny Konrad Ciechanowski Wydawnictwo Interpress, 1988, page 13

- ↑ Gdańsk 1939: wspomnienia Polaków-Gdańszczan Brunon Zwarra Wydawnictwo Morskie, 1984, p 13

- ↑ Avalon Project : The French Yellow Book : No. 113 - M. Coulondre, French Ambassador in Berlin, to M. Georges Bonnet, Minister for Foreign Affairs. Berlin, April 30, 1939

- ↑ Rich 1974, p. 398.

- ↑ Strobl 2000, pp. 36–60.

- 1 2 Strobl 2000, p. 84.

- ↑ Strobl 2000, p. 85.

- ↑ Hitler 2003.

- ↑ Strobl 2000, p. 61.

- 1 2 3 4 Rich 1974, p. 396.

- ↑ Nicosia 2000, p. 73.

- ↑ Nicosia 2000, p. 74.

- ↑ Hildebrand 1973, p. 99.

- ↑ Hildebrand 1973, p. 96.

- ↑ Hildebrand 1973, p. 105.

- ↑ Hildebrand 1973, pp. 100–105.

- ↑ Pinkus 2005, p. 259.

- ↑ Rich 1974, p. 421.

- ↑ Sanders 2005, p. xxiv.

- 1 2 Sanders 2005, p. 188.

- ↑ Rich 1974, p. 397.

- ↑ Weinberg 2006, p. 35.

- ↑ David Nicholls. Adolf Hitler: A Biographical Companion. ABC-CLIO. p. 211.

- ↑ Hitler: diagnosis of a destructive prophet. Oxford University Press, 2000. p. 418

- 1 2 Ingo Haar, Michael Fahlbusch. German Scholars and Ethnic Cleansing, 1919-1945. p. 130.

- 1 2 Alan J. Levine. Race Relations Within Western Expansion. Praeger Publishers, 1996. p. 97.

- ↑ Andrew Vincent. Modern Political Ideologies. John Wiley & Sons, 2009, p. 308.

- ↑ Alex Scobie. Hitler's State Architecture: The Impact of Classical Antiquity. pp. 21-22.

- 1 2 R J B Bosworth. Mussolini's Italy: Life Under the Dictatorship, 1915-1945

- 1 2 David B. Dennis. Inhumanities: Nazi Interpretations of Western Culture. Cambridge University Press, 2012. p. 17-19.

- ↑ Jo Groebel, Robert A. Hinde. Aggression and War: Their Biological and Social Bases. Cambridge University Press, 1989. p. 159.

- 1 2 Rich 1974, p. 317.

- ↑ Wedekind 2006, pp. 113, 122–123.

- ↑ Norman Cameron, R. H. Stevens. Hitler's Table Talk, 1941-1944: His Private Conversations. Enigma Books, 2000. p. 287.

- ↑ Richard Breiting, Adolf Hitler, Édouard Calic (ed.). Secret conversations with Hitler:the two newly-discovered 1931 interviews. John Day Co., 1971. p. 77.

- 1 2 3 R. J. B. Bosworth. Mussolini. Bloomsbury, 2014.

- 1 2 Jens Woelk, Francesco Palermo, Joseph Marko. Tolerance Through Law: Self Governance and Group Rights In South Tyrol. Leiden, Netherlands: Koninlijke Brill NV, 2008. p. 5.

- ↑ Jens Woelk, Francesco Palermo, Joseph Marko. Tolerance Through Law: Self Governance and Group Rights In South Tyrol. Leiden, Netherlands: Koninlijke Brill NV, 2008. p. 6.

- 1 2 Christian Leitz. Nazi Foreign Policy, 1933-1941: The Road to Global War. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: p. 10.

- ↑ H. James Burgwyn. Italian foreign policy in the interwar period, 1918–1940. Wesport, Connecticut, USA: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1997. p. 81.

- ↑

- 1 2 Rolf Steininger. South Tyrol: A Minority Conflict of the Twentieth Century. p. 49.

- 1 2 Allen Welsh Dulles, Neal H. Petersen, United States. Office of Strategic Services. Bern Office. From Hitler's Doorstep: The Wartime Intelligence Reports of Allen Dulles, 1942-1945. Pennsylvania State Press, 1996.

- 1 2 Dr Susan Zuccotti, Furio Colombo. The Italians and the Holocaust: Persecution, Rescue, and Survival. University of Nebraska Press paperback edition, 1996. p. 148.

- 1 2 Petacco 2005, p. 50.

- ↑ Kersten 1947, p. 186.

- ↑ Rich 1974, pp. 320, 325

- ↑ Rolf Steininger. South Tyrol: A Minority Conflict of the Twentieth Century. p. 69.

- ↑ Giuseppe Motta. The Italian Military Governorship in South Tyrol and the Rise of Fascism. English translation edition. Edizioni Nuova Cultura, 2012. p. 104.

- ↑ Arrigo Petacco. Tragedy Revealed: The Story of Italians from Istria, Dalmatia, and Venezia Giulia, 1943-1956. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: University of Toronto Press, 2005. p. 50.

- 1 2 Kroener, Müller, Umbreit (2003), Germany and the Second World War: Volume V/II: Organization and Mobilization in the German Sphere of Power: Wartime Administration, Economy, and Manpower Resources 1942-1944/5, p. 79, ISBN 0-19-820873-1

- 1 2 Wedekind 2003, Nationalsozialistische Besatzungs- und Annexionspolitik in Norditalien 1943 bis 1945, pp. 100–101

- ↑ Rich 1974, p. 331.

- 1 2 Madajczyk.

- ↑ Rich 1974, p. 329.

- ↑ Poprzeczny 2004, p. 181.

- ↑ Nicholas 2006, pp. 330-331

- 1 2 3 Stein 1984, pp. 145–148.

- Bibliography

- Ackermann, Josef (1970). Heinrich Himmler als Ideologe (in German). Musterschmidt. LCCN 75569891.

- Bohn, Robert (1997). Die deutsche Herrschaft in den "germanischen" Ländern 1940-1945 (in German). Steiner. ISBN 3-515-07099-0.

- Boog, Horst (2001). Germany and the Second World War. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-822888-0.

- Bramstedt, E. K. (2003). Dictatorship and Political Police: The Technique of Control by Fear. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-17542-9.

- Brockmann, Stephen (2006). Nuremberg: the imaginary capital. Camden House. ISBN 978-1-57113-345-8.

- Crozier, Andrew J (1997). The Causes of the Second World War. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-18601-8.

- De Jong, Louis (1969). Het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in de tweede wereldoorlog: Voorspel (in Dutch). M. Nijhoff.

- De Jong, Louis (1974). Het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in de tweede wereldoorlog: Maart '41 - Juli '42 (in Dutch). M. Nijhoff.

- Domarus, Max (2007). The essential Hitler: speeches and commentary. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-0-86516-665-3.

- Elvert, Jürgen (1999). Mitteleuropa!: deutsche Pläne zur europäischen Neuordnung (1918-1945) (in German). Verlag Wiesbaden GmbH. ISBN 3-515-07641-7.

- Fest, Joachim C. (1973). Hitler. Verlagg Ulstein. ISBN 0-15-602754-2.

- Fink, Jürg (1985). Die Schweiz aus der Sicht des Dritten Reiches, 1933-1945 (in German). Schulthess. ISBN 3-7255-2430-0.

- Gildea, Robert; Wieviorka, Olivier; Warring, Anette (2006). Surviving Hitler and Mussolini: Daily Life in Occupied Europe. Berg Publishers. ISBN 1-84520-181-7.

- Goebbels, Joseph; Taylor, Fred (1982). The Goebbels diaries, 1939-1941. H. Hamilton. ISBN 0-241-10893-4.

- Grafton, Anthony; Most, Glenn W.; Settis, Salvatore (2010). The Classical Tradition. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-03572-0.

- Griffiths, Tony (2004). Scandinavia. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 1-85065-317-8.

- Halbrook, Stephen P. (1998). (1998). Target Switzerland: Swiss Armed Neutrality in World War II. Sarpedon. ISBN 0-306-81325-4.

- Hamacher, Werner; Hertz, Thomas; Keenan, Anette (1989). Responses: On Paul de Man's Wartime Journalism. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-7243-9.

- Hattstein, Markus (2006). "Holy Roman Empire, The". In Blamires, Paul; Jackson. World Fascism: A Historical Encyclopedia. 1. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-57607-940-6.

- Hildebrand, Klaus (1973). The Foreign Policy of the Third Reich. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-02528-8.

- Hillgruber, Andreas; Picker, Henry (1968). Hitlers Tischgespräche im Führerhauptquartier 1941–1942.

- Hitler, Adolf (1926). Mein Kampf. Eher Verlag.

- Hitler, Adolf (2000). Bormann, Martin, ed. Hitler's Table Talk 1941-1944. trans. Cameron, Norman; Stevens, R.H. (3rd ed.). Enigma Books. ISBN 1-929631-05-7.

- Hitler, Adolf (2003). Weinberg, Gerhard L., ed. Hitler's Second Book: The Unpublished Sequel to Mein Kampf (PDF). Enigma Books. ISBN 1-929631-16-2.

- Housden, Martyn (2000). Hitler: study of a revolutionary?. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-415-16359-5.

- Janssens, Jozef (2005). Superhelden op perkament: middeleeuwse ridderromans in Europa (in Dutch). Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 90-5356-822-0.

- Kersten, Felix (1957). The Kersten Memoirs, 1940-1945. Hutchinson. LCCN 56058163.

- Kersten, Felix (1947). The Memoirs of Doctor Felix Kersten. Ernst Morwitz (trans.). Doubleday & Company. LCCN 47001801.

- Kieler, Jørgen (2007). Resistance Fighter: A Personal History of the Danish Resistance Movement, 1940-1945. Gefen Publishing House. ISBN 965-229-397-0.

- Kroener, Bernhard; Müller, Rolf-Dieter; Umbreit, Hans (2003). Germany and the Second World War: Organization and Mobilization of the German Sphere of Power. Wartime Administration, Economy, and Manpower Resources 1942-1944/5. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820873-1.

- Leitz, Christian (2000). Nazi Germany and Neutral Europe During the Second World War. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-5069-3.

- Lipgens, Walter (1985). Documents on the History of European Integration: Continental Plans for European Union 1939-1945. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-009724-9.

- Madajczyk, Czeslaw (1962). "Generalplan East: Hitler's Master Plan for Expansion". Polish Western Affairs. III (2).

- Morgan, Philip (2003). Fascism in Europe, 1919-1945. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-16942-9.

- Nicholas, Lynn H. (2006). Cruel World: The Children of Europe in the Nazi Web. Vintage Books. ISBN 0-679-77663-X.

- Nicosia, Francis R. (2000). The Third Reich and the Palestine Question. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 0-7658-0624-X.

- Petacco, Arrigo (2005). A Tragedy Revealed: The Story of the Italian Population of Istria, Dalmatia, and Venezia Giulia, 1943-1956. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-3921-9.

- Pinkus, Oscar (2005). The War Aims and Strategies of Adolf Hitler. McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-2054-5.

- Poprzeczny, Joseph (2004). Odilo Globocnik: Hitler's Man in the East. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-1625-7.

- Rich, Norman (1974). Hitler's War Aims: The Establishment of the New Order. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-33290-X.

- Rothwell, Victor (2005). War Aims in the Second World War: the War Aims of the Major Belligerents. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-1503-2.

- Sanders, Paul (2005). The British Channel Islands under German Occupation, 1940-1945. Paul Sanders. ISBN 0-9538858-3-6.

- Sager, Alexander; Winkler, Heinrich August (2007). Germany: The Long Road West. 1933-1990. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-926598-4.

- Schöttler, Peter (2003). "Eine Art "Generalplan West": Die Stuckart-Denkschrift vom 14. Juni 1940 und die Planungen für eine neue deutsch-französische Grenze im Zweiten Weltkrieg". Sozial Geschichte (in German). 18 (3): 83–131.

- Speer, Albert (1970). Inside the Third Reich. Macmillan Company. LCCN 70119132.

- Speer, Albert (1976). Spandau: The Secret Diaries. Macmillan Company.