Green-Wood Cemetery

|

Green-Wood Cemetery | |

|

Richard M. Upjohn's Gothic revival northern entrance to the cemetery, built in 1861-65, has been a New York City landmark since 1966[1] (2015) | |

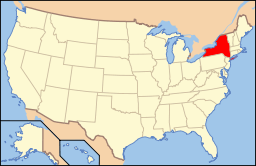

| Location | Brooklyn, New York City |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°39′08″N 73°59′28″W / 40.65222°N 73.99111°WCoordinates: 40°39′08″N 73°59′28″W / 40.65222°N 73.99111°W |

| Area | 478 acres (1.9 km2) |

| Built | 1838[2] |

| Architect |

Cemetery: David Bates Douglass Gates: Richard M. Upjohn Chapel: Warren & Wetmore Weir Greenhouse: G. Curtis Gillespie |

| NRHP Reference # | 97000228 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | March 8, 1997[3] |

| Designated NHL | September 20, 2006[4] |

| Designated NYCL |

Gates: April 19, 1966[5] Weir Greenhouse: April 13, 1982[6] Fort Hamilton Parkway Gate & Green-Wood Cemetery Chapel: April 12, 2016[7] |

Green-Wood Cemetery was founded in 1838 as a rural cemetery in Kings County, New York.[8] Like other early rural cemeteries, Green-Wood was founded in a time of rapid urbanization when churchyards in New York City were becoming overcrowded.

Located in Greenwood Heights, Brooklyn, the cemetery lies several blocks southwest of Prospect Park, between Park Slope, Windsor Terrace, Borough Park, Kensington, and Sunset Park. Paul Goldberger in The New York Times, wrote that it was said "it is the ambition of the New Yorker to live upon the Fifth Avenue, to take his airings in the Park, and to sleep with his fathers in Green-Wood".[9]

The gates of the cemetery were designated a New York City landmark in 1966,[5] and the Weir Greenhouse, used as a visitor's center, in 1982. The cemetery was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1997 and was granted National Historic Landmark status in 2006 by the U.S. Department of the Interior.[2] The Fort Hamilton Parkway Gate and the cemetery's chapel were designated as landmarks by New York City in 2016.[7]

The popularity of Green-Wood Cemetery inspired a competition to design a "Central Park" for NYC. It essentially inspired the creation of Central Park and Prospect Park.

History

Inspired by Pére Lachaise Cemetery in Paris and Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts,[11] where a cemetery in a naturalistic park-like landscape in the English manner was first established, Green-Wood was able to take advantage of the varied topography provided by glacial moraines. Battle Hill, the highest point in Brooklyn, is on cemetery grounds, rising approximately 200 feet above sea level. It was the site of an important action during the Battle of Long Island on August 27, 1776. A Revolutionary War monument by Frederick Ruckstull, Altar to Liberty: Minerva, was erected there in 1920. From this height, the bronze Minerva statue gazes towards the Statue of Liberty across New York Harbor.[12]

The cemetery was the idea of Henry Evelyn Pierrepont,[13] a Brooklyn social leader. The Pierrepont papers deposited at the Brooklyn Historical Society contain material about the organizing of Green-Wood Cemetery. It was a popular tourist destination in the 1850s, and by the early 1860s it was drawing annual crowds second in size only to Niagara Falls. Most famous New Yorkers who died during the second half of the nineteenth century were buried there. Green-Wood Cemetery is still operating with approximately 600,000 graves and 7000 trees spread out over 478 acres (1.9 km2). The rolling hills and dales, several ponds and an on-site chapel provide an environment that still draws visitors.

There are several famous monuments located there, including a statue of DeWitt Clinton, and a memorial erected by James Brown, president of Brown Brothers bank and the Collins Line, to the six members of his family lost in the SS Arctic disaster of 1854. This incorporates a sculpture of the ship, half-submerged by the waves. As well as a Civil War Memorial, during the Civil War, Green-Wood Cemetery created the "Soldiers' Lot" for free veterans' burials.

The gates were designed by Richard Upjohn in Gothic Revival style. The main entrance to the cemetery was built in 1861-65 of Belleville, New Jersey brownstone. The sculptured groups on Nova Scotia limestone panels depicting biblical scenes of death and resurrection from the New Testament including Lazarus, The Widow's Son, and Jesus' Resurrection over the gateways are the work of sculptor John M. Moffitt.[11] A Designated Landmarks of New York plaque was erected on it in 1958 by the New York Community Trust, and it was designated an official New York City landmark in 1966.[1]

Several wooden shelters were also built, including one in a Gothic Revival style, one resembling an Italian villa, and another resembling a Swiss chalet.[14] A descendent colony of monk parakeets that are believed to have escaped their containers while in transit now nests in the spires of the gate, as well as other areas in Brooklyn.[15][16]

On December 5, 1876, the Brooklyn Theater Fire claimed the lives of at least 278 individuals, with some accounts reporting over 300 dead. Out of that total, 103 unidentified victims were interred in a common grave at Green-Wood Cemetery. An obelisk near the main entrance at Fifth Avenue and 25th Street marks the burial site. More than two dozen identified victims were interred individually in separate sections at the Cemetery of the Evergreens in Brooklyn. Also buried at the cemetery are 6 British Commonwealth service personnel whose graves are registered by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, 3 from World War I and 3 from World War II, among the latter being Leading Aircraftsman Remsen Taylor Williams (died 1941 aged 26), Royal Canadian Air Force, who is buried in the Steinway Vault.[17]

Green-Wood has remained non-sectarian, but was generally considered a Christian burial place for white Anglo-Saxon Protestants of good repute. One early regulation was that no one executed for a crime, or even dying in jail, could be buried there. Although he died in the Ludlow Street Jail, the family of the infamous "Boss" Tweed managed to circumvent this rule.[18] The cemetery's chapel was completed in 1911. It was designed by the architectural firm of Warren and Wetmore, who also designed Grand Central Terminal, the Commodore Hotel, the Yale Club and many other buildings. The architecture of the chapel is a reduced version of Christopher Wren's Thomas Tower at Christ Church College in Oxford, and was restored in 2001.[10]

In 1999, The Green-Wood Historic Fund, a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit institution, was created to continue preservation, beautification, educational programs and community outreach as the current "working cemetery" evolves into a Brooklyn cultural institution.

The vandalism on August 21, 2012 was one of the worst cases encountered in Green-Wood. Individual(s) was said to have jumped the fence and damage about 50 monuments and memorials.

In 2012, Hurricane Sandy toppled or damaged at least 292 of the mature trees, 210 gravestones, and 2 mausoleums in the cemetery. The damage was estimated at $500,000.[19]

In December 2012 the controversial and much traveled statue ‘’The Triumph of Civic Virtue’' by Frederick MacMonnies was moved to Green-Wood.[20]

Also in 2012, the Angel of Music made by sculptors Giancarlo Biagi and Jill Burkee, memorialized Louis Moreau Gottschalk.

In August 2013, in partnership with the Connecticut Society of the Cincinnati, signage in the Battle Hill area of the cemetery was updated to reflect new research on Battle Hill's importance in the Battle of Brooklyn.[21]

The Historic Fund’s Civil War Project

The Historic Fund's Civil War Project, an effort to identify and remember Civil War veterans buried at Green-Wood, was born of the enthusiasm felt at the rededication ceremony of Civil War Soldiers' Monument. These early graves have either sunk into the soil, been damaged, or have their markers erased.

Notable burials

_4_crop.jpg)

- Samuel Akerly (1785–1845), founder of the New York Institute for the Blind

- Augustus Chapman Allen (1806–1864), co-founder of the City of Houston

- Harvey A. Allen (1818?–1882), United States Army officer, was Commander of the Department of Alaska 1871–1873

- Albert Anastasia (1903–1957), mobster and contract killer for Murder, Inc.

- Othniel Boaz Askew (1972–2003; cremated), politician and assassin of New York City Council member James E. Davis, whose remains were relocated to another cemetery

- James Bard (1815–1897), marine artist, buried in unmarked grave

- Peter Townsend Barlow (1857–1921), New York City Magistrate

- Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960–1988), artist

- William Holbrook Beard (1824–1900), painter of Bulls and Bears representing the market cycle; a bear statue sits on top of his headstone

- Henry Ward Beecher (1813–1887), abolitionist

- George Wesley Bellows (1882–1925), painter

- James Gordon Bennett, Sr. (1795–1872), founder/publisher of the New York Herald

- Richard Rodney Bennett (1936–2012; cremated), composer of film, TV and concert music

- Henry Bergh (1818–1888), founder of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals

- Leonard Bernstein (1918–1990), pianist, composer, and conductor; alongside his wife, actress Felicia Montealegre (1922-1978)

- Jane Augusta Blankman (1823–1860), courtesan

- Samuel Blatchford (1820–1893), U.S. Supreme Court Justice

- Stanley Bosworth (1927-2011), Founding headmaster of prestigious Saint Ann's School

- Andrew Bryson (1822–1892), United States Navy rear admiral

- Charlotte Canda, a debutante killed in a carriage accident on her 17th birthday

- Elliott Carter (1908–2012), composer

- Alice Cary (1820–1871), poet, author

- Phoebe Cary (1824–1871), poet, author

- George Catlin (1796–1872), painter of Native Americans in the Old West

- Henry Chadwick (1824–1908), Baseball Hall of Fame member (memorial)

- William Merritt Chase (1849–1916), painter, teacher

- Kate Claxton (1850–1924), American theatre actress noted for her role of Louise in the play The Two Orphans[22]

- DeWitt Clinton (1769–1828), unsuccessful U.S. presidential candidate 1812; U.S. Senator from New York; seventh and ninth Governor of New York

- William J. Coombs (1833–1922), U.S. Congressman from Brooklyn

- George H. Cooper (1821–1891), United States Navy rear admiral

- Peter Cooper (1791–1883), inventor, manufacturer, abolitionist, founder of Cooper Union

- James Creighton, Jr. (1841–1862), first pitcher to throw a fastball[23]

- Edwin Pearce Christy (1815–1862), minstrel, known for performing the Stephen Foster song "Old Folks at Home" (aka "Swanee River")

- George Washington Cullum (1809–1892), Superintendent of the United States Military Academy

- Nathaniel Currier (1813–1888), artist ("Currier and Ives")

- Duncan Curry (1812–1894), baseball pioneer and insurance executive

- Elizabeth Cushier (1837–1931), professor of medicine and for 25 years before her retirement in 1900, one of New York's most prominent obstetricians

- Bronson M. Cutting (1888–1935), United States Senator from New Mexico (1927–1928; 1929–1935)

- Marcus Daly (1841–1900), Irish-born copper industrialist in Montana

- James E. Davis (1962–2003), assassinated City Councilman, was buried here for a few days; upon learning his killer's ashes were also in Green-Wood, his family had his body exhumed and reinterred in the Cemetery of the Evergreens[24]

- Charles Schuyler De Bost (1826–1895), baseball pioneer

- Richard Delafield (1798–1873), Chief of Engineers and Superintendent of West Point

- Francis E. Dorn (1911–1987), U.S. Naval Commander, attorney and member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New York's 12th congressional district

- Mabel Smith Douglass (1874–1933), founder and first dean of the New Jersey College for Women

- Thomas Clark Durant (1820–1885), key figure in building the First Transcontinental Railroad

- James Durno (1795–1873), husband of labor activist Sarah Bagley (1806–1883)

- Fred Ebb (1928–2004), lyricist

- Charles Ebbets (1859–1925), baseball team (Brooklyn Dodgers) owner; built Ebbets Field

- Elizabeth F. Ellet (1818–1877), American writer and poet

- George Edwin Ewing (1828–1884), Scottish sculptor

- Charles Feltman (1841–1910), claimed to be the first person to put a hot dog on a bun

- Edward Ferrero (1831–1899), American Civil War General at the Battle of the Crater and in the Appomattox Campaign

- Edwin Forbes (1839–1895), American Civil War and postbellum artist, illustrator, and etcher

- Isaac Kaufmann Funk (1839–1912), American editor, lexicographer, publisher, and spelling reformer

- Joey Gallo (1929–1972), mobster

- William Delbert Gann (1878-1955), Stock Market author and visionary

- Asa Bird Gardiner (1839–1919), controversial soldier, attorney, and prosecutor

- Robert Selden Garnett (1819–1861), brigadier general of the Confederate States Army and the first general killed in the American Civil War

- Henry George (1839–1897), writer, politician and economist

- Henry George, Jr. (1862–1916), United States Representative from New York

- Louis Moreau Gottschalk (1829–1869), composer

- John Franklin Gray (1804–1882), the first practitioner of Homeopathy in the United States

- Horace Greeley (1811–1872), unsuccessful U.S. presidential candidate 1872; founder of the New York Tribune

- Robert Stockton Green (1831–1895), Governor of New Jersey

- Rufus Wilmot Griswold (1815–1857), literary critic

- Edward Wheeler Hall (1881–1922), one of the victims of the Hall–Mills murder case

- Frances Noel Stevens Hall (1874–1942), wife of Edward and suspect in the Hall–Mills murder

- Paul Hall (1914–1980), labor leader

- Henry Wager Halleck (1815–1872), U.S. Army Commander during the middle part of the American Civil War

- William Stewart Halsted (1852–1922), pioneer in American medicine and surgery, often credited as the "Father of Modern American Surgery"

- Jeremiah Hamilton (1806/1807–1875), "the only black millionaire in New York" around the time of the American Civil War

- John Hardy (1835–1913), member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New York

- Townsend Harris (1804–1878), first U.S. Consul General to Japan

- Nathaniel H. Harris (1834–1900), Confederate brigadier general during the American Civil War[25]

- William S. Hart (1864–1946), star of silent "Western" movies

- John A. Hartwell (1861–1940), noted athlete, philanthropist, pioneer in American surgery, and personal physician of Theodore Roosevelt

- Thomas Hastings (1784–1872), wrote the music to the hymn "Rock of Ages"

- Genevieve Hecker (1883–1960), champion golfer

- Joseph Henderson (1826–1890), notable harbor pilot

- Philip A. Herfort (1851–1921), violinist and orchestra leader

- Abram S. Hewitt (1822–1903), Teacher, lawyer, iron manufacturer, U.S. Congressman, and a mayor of New York; son-in-law of Peter Cooper

- Henry B. Hidden (c. 1839–1862), American Civil War cavalry officer

- DeWolf Hopper (1858–1935), actor

- Elias Howe (1819–1867), invented the sewing machine (see Walter Hunt)

- James Howell (1829–1897), 19th mayor of Brooklyn

- Walter Hunt (1785–1869), invented the safety pin

- Richard Isay (1934–2012), psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, author, gay activist

- James Merritt Ives (1824–1895), artist ("Currier and Ives")

- Paul Jabara (1948–1992), actor, singer and songwriter

- Leonard Jerome (1817–1891), entrepreneur, grandfather of Winston Churchill

- Eastman Johnson (1824–1906), American painter, and co-founder of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

- James Weldon Johnson (1871–1938), American author, educator, lawyer, diplomat, songwriter, and civil rights activist. Author of "Lift Every Voice and Sing"

- Tom L. Johnson (1854–1911), former mayor of Cleveland, Ohio

- Laura Keene (1826–1873), actress who was on stage when Lincoln was shot

- Florence La Badie (1888–1917), actress

- John La Farge (1835–1910), artist

- Laura Jean Libbey (1862–1924), popular "dime-store" novelist

- Brockholst Livingston (1757–1823), U.S. Supreme Court Justice

- William Livingston (1723–1790), signer of the U.S. Constitution; first Governor of New Jersey

- William Lewis Lockwood (1836–1867), one of the founders of the Sigma Chi Fraternity

- Pierre Lorillard IV (1833–1901), tobacco tycoon, introduced the tuxedo to the U.S.

- James Maury (consul) (1746–1840), first U.S. consul to Liverpool, England

- Susan McKinney Steward (1847–1918), one of the first black women to earn a medical degree, and the first in the state of New York

- Ormsby M. Mitchel (1805–1862), American astronomer and major general in the American Civil War

- Henry James Montague (1840–1878), stage actor[26]

- Lola Montez (1821–1861), actress and mistress of many notable men among them King Ludwig I of Bavaria

- Frank Morgan (1890–1949), actor (The Wizard of Oz)

- Samuel F. B. Morse (1791–1872), invented Morse code, language of the telegraph

- William Niblo (1790–1878), also known as Billy Niblo, the owner of Niblo's Garden

- Violet Oakley (1874–1961), artist

- James Kirke Paulding (1779–1860), U.S. Secretary of the Navy under Martin Van Buren; thought to be "author" of "Peter picked a peck of pickled peppers"[27]

- Mary Ellis Peltz (1896–1981), American drama and music critic, magazine editor, poet and writer on music.

- Anson Greene Phelps (1781–1853), founder of Phelps, Dodge mining and copper company

- Duncan Phyfe (1768–1854), cabinetmaker

- Hezekiah Pierrepont (1768–1838) merchant and founder of Brooklyn Heights, Brooklyn

- William "Bill The Butcher" Poole (1821–1855), a member of the Bowery Boys gang and the Know Nothing political party; also a bare-knuckle boxer

- Henry Jarvis Raymond (1820–1869), American journalist and politician and founder of The New York Times

- Samuel C. Reid (1783–1861), suggested the design upon which all U.S. flags since 1818 have been based

- Alice Roosevelt (1861–1884), first wife of U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt

- Martha Bulloch Roosevelt (1834–1884), mother of U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt

- Robert Roosevelt (1829–1906), uncle of U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt

- Theodore Roosevelt, Sr. (1831–1878), father of U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt

- Henry Rutgers (1745–1830), Revolutionary War hero, philanthropist, namesake of Rutgers University

- Ira Sankey (1840–1908), hymn composer

- Frederick August Otto Schwarz (1836–1911), founder of specialty toy retailer FAO Schwarz

- Eli Siegel (1902–1978), poet, educator, founder of the philosophy Aesthetic Realism

- John D. Sloat (1781–1867), United States Navy commodore, claimed California for the U.S.

- Henry Warner Slocum (1827–1894), Union general in the American Civil War, U.S. Representative from New York

- Ole Singstad (1882–1969), Norwegian-American civil engineer, designed Lincoln Tunnel and others

- Francis Barretto Spinola (1821–1891), first Italian-American elected to the U.S. House of Representatives

- Emma Stebbins (1815–1882), artist, sculptor of Bethesda Fountain

- George Steers-(1819-1856), designer of the Yacht America, winner of the first America's Cup.

- Henry Steinway (1797–1871), founder of Steinway & Sons, piano manufacturers

- William Steinway (1836–1896), son of Henry Steinway, and founder of Steinway, New York

- John Austin Stevens Jr. (1827–1910), founder of Sons of the Revolution

- James S. T. Stranahan (1808–1898), "Father of Prospect Park", instrumental promoter of the park, the Brooklyn Bridge, and the consolidation of Brooklyn into Greater New York

- Francis Scott Street (1831–1883), co-owner of Street & Smith publishers

- Silas Stringham (1798–1876), long serving United States Navy officer during the American Civil War and War of 1812

- George Crockett Strong (1832–1863), Union brigadier general in the American Civil War

- Thomas William "Fightin' Tom" Sweeny (1820–1892), Irish immigrant and American Civil War general

- Richard Termini Sr. (1929–1982), Father of musician Richard Termini

- John Thomas (1805–1871), founder of The Christadelphians

- Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848–1933), artist

- Alfred Toftenes (1881–1918), Norwegian Chief Officer blamed for the collision that sank the Empress of Ireland

- Matilda Tone (or Mathilda) (1769–1849), widow of Irish rebel Wolfe Tone

- George Francis Train (1829–1904), railroad promoter

- Juan Trippe (1899–1981), airline pioneer, headed Pan Am from 1927 to 1968

- Robert Troup (1756–1832), Revolutionary War hero, New York State assemblyman and Judge; body moved to Green-Wood in 1872[28]

- William Magear "Boss" Tweed (1823–1878), notorious New York political boss, member of the U.S. House of Representatives and New York State Senate

- Camilla Urso (Camille Urso) (1842–1902), French violinist

- Steven C. Vincent (1955–2005), American journalist and author kidnapped and murdered in Iraq August 2005

- Leopold von Gilsa (1824–1870), American Civil War colonel and brigade commander

- Charles S. Wainwright (1826–1907), American Civil War colonel and artillery officer

- Hugo Wesendonck (1817–1900) Founder of the Germania Life Insurance Company, now Guardian Life

- Henry John Whitehouse (1803–1874), Episcopal Bishop

- Thomas R. Whitney (1807–1858), member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New York

- Barney Williams (1824–1876), Irish-American actor-comedian

- Beekman Winthrop (1874–1940), governor of Puerto Rico from 1904 to 1907, and later an Assistant Secretary of the Treasury

- Jonathan Young (1826–1885), United States Navy commodore

- William West Durant (1850–1934) son of Thomas Clark Durant and designer and developer of camps in the Adirondack Great Camp style

Gallery

European beech tree and mausoleums

European beech tree and mausoleums Largest tulip tree in the cemetery

Largest tulip tree in the cemetery Large ginkgo tree

Large ginkgo tree Camperdown elm tree

Camperdown elm tree Two old sassafras trees

Two old sassafras trees Koi pond in the Tranquility Garden section of the Cemetery

Koi pond in the Tranquility Garden section of the Cemetery

In popular culture

- In the season 2 episode of Daredevil "Penny and Dime," the cemetery is where Matt Murdock brings a wounded Frank Castle after rescuing him from the Kitchen Irish. Matt is later shown standing on top of the entrance archway while the police are arresting Frank.

- In season 1 of Iron Fist, the cemetery is the location of a memorial to Danny Rand and his family.

See also

- List of cemeteries in New York

- List of mausoleums

- List of New York City Landmarks

- List of National Historic Landmarks in New York City

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Kings County, New York

References

Notes

- 1 2 New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission; Dolkart, Andrew S. (text); Postal, Matthew A. (text) (2009), Postal, Matthew A., ed., Guide to New York City Landmarks (4th ed.), New York: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-470-28963-1, p. 250

- 1 2 "Green-Wood Cemetery". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. 2007-09-14.

- ↑ National Park Service (2007-01-23). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ "Green-Wood Cemetery". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. 2007-09-14.

Green-Wood Cemetery, established in 1838, was the largest and most varied of the early American rural cemeteries. Its scale, diverse topography, and intended civic prominence made it the prototype for how a cemetery with Picturesque landscaping could be created in contrast to the rapidly expanding cities of the 19th century. Inspired by Alexander Jackson Downing, the most nationally prominent landscape designer and author in antebellum America, David Bates Douglass conceived the overall plan for the Picturesque landscape, executed with complementary Gothic Revival buildings by Richard Upjohn and his son Richard Michell Upjohn

- 1 2 Staff (April 19, 1966) Green-Wood Cemetery Gates Designation Report" New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission

- ↑ Staff (April 13, 1982) "Weir Greenhouse Designation Report" New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission

- 1 2 Hurley, Marianne (April 12, 2016) "Fort Hamilton Parkway Entrance and Green=Wood Cemetery Chapel Designation Report" New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission

- ↑ Collins, Glenn (April 1, 2004). "Ground as Hallowed as Cooperstown; Green-Wood Cemetery, Home to 200 Baseball Pioneers". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-03-28.

Before A-Rod and Jeter, there were J-Creigh and Woodward. That would be James Creighton, Jr., the world's first true baseball star, and John B. Woodward, an outfielder who became a Union general in the Civil War. Both played for the Excelsior Club – sort of the Yankees of the early 1860s – and now both reside in the Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn.... Mr. Nash discovered some monuments, like that of Duncan Curry, by sheer chance, while walking through the cemetery. Curry, first president of the Knickerbocker Baseball Club, is immortalized with a monument that proudly dubs him Father of Baseball because he headed the club that scholars say first codified many of the game's rules.... Another Green-Wood resident, DeWolf Hopper, a thespian, delivered a rendition of the Ernest Thayer poem, Casey at the Bat, shortly after it was published in 1888, and proceeded to perform it more than 10,000 times over the next half-century. One of his six marriages was to a Hollywood socialite who took his name: Hedda Hopper. At Tulip Hill, the imposing granite vault of the three Patchen brothers – Sam Patchen (shortstop), Joe Patchen (right field) and Edward Patchen (infielder) – is the only crypt of early baseball players, the Alou brothers of their time.... A happier story is that of Charles J. Smith, one of the great players of the 1860s, Mr. Richman said. He was buried in a seemingly unmarked grave at Green-Wood. But investigation by a grounds crew discovered his monument last year, a few feet underground, where it had sunk. It has now been restored.

- ↑ Paul Goldberger (November 17, 1977). "Design Notebook; Pastoral Green-Wood cemetery is a lesson in 19th-century taste". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-09-23.

'Before there was a Central Park and a Prospect Park, people came to GreenWood,' said William J. Ward. Green-Wood is not a park, it is not a playground and it is not a rural outpost; it is a cemetery in southwest Brooklyn. But there is no mystery as to why it was once popular for Sunday outings--Green-Wood is as lush a landscape as exists anywhere in the built-up boroughs of New York.

(subscription required) - 1 2 "Chapel Services" Green-Wood Cemetery website

- 1 2 Moylan, Richard J. "Green-Wood Cemetery" in Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (2010), The Encyclopedia of New York City (2nd ed.), New Haven: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-11465-2, pp. 557-58

- ↑ Daniel B. Schneider (1998-05-24). "F.Y.I.". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-08-11.

- ↑ "Henry Evelyn Pierrepont". Findagrave.com. Retrieved 2011-11-02.

- ↑ "Pierrepont Family Memorial" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 21, 2007. Retrieved September 23, 2007.

Henry Evelyn Pierrepont was known as the "first citizen" of Brooklyn for good reason. He, along with his father Hezekiah B. and mother Anna Maria before him, played a significant role in the planning of Brooklyn as a physical city, its crucial ferry services to New York, and the establishment of Green-Wood Cemetery itself.

- ↑ "BrooklynParrots.com: A Web Site About the Wild Parrots of Brooklyn". Retrieved 2007-09-23.

The beautiful Civil War-era gate to Greenwood Cemetery is spectacular in its own right; add vociferous parrots and you've got one of the most sublime, most surreal locales on the planet.

- ↑ Pesquarelli, Adrianne. "Gotham Gigs; Birdman". Crain's New York Business. Retrieved 2007-09-23. The article presents information concerning the year-round tours led by Steve Baldwin in Brooklyn, New York to the nests of parrots. Baldwin volunteers to lead walking tours to the nests of an extended family of wild Quaker parrots that escaped from a shipping crate at JFK International Airport in the late 1960s.

- ↑ CWGC Cemetery Report. Breakdown obtained from casualty record.

- ↑ The Irish of Green-Wood Cemetery, Michael Burke, Irish America magazine

- ↑ David W. Dunlap (November 25, 2012). "Many Cemeteries Damaged, but Green-Wood Bore the Brunt of the Storm". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-11-26.

High winds destroyed or badly damaged at least 292 of the mature trees ... He estimated the clean-up would cost at least $500,000....

- ↑ Colangelo, Lisa (December 16, 2012). "Triumph of Civic Virtue is moved to Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn". nydailynews.com. Mortimer Zuckerman. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- ↑ Richman, Jeff (August 27, 2013). "Commemorating the Battle of Brooklyn". green-wood.com. The Green-Wood Historic Fund. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- ↑ James, Edward T.; James, Janet Wilson; Boyer, Paul S. "Notable American women, 1607–1950: a biographical dictionary", p. 345, Harvard University Press, 1971. ISBN 0-674-62734-2. Accessed June 28, 2009.

- ↑ Schweber, Nate (October 18, 2012). "Recalling a New Pitch and a Strange Death". The New York Times.

- ↑ Mulligan, Thomas S. (August 3, 2003). "Slain New York City Councilman Reburied; Reinterment occurred after family learned his killer's ashes were in the same cemetery.". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

'If she had known that Askew's cremated remains were at Green-Wood, she never would have agreed to have her son buried there,' Hill said.

- ↑ Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher, Civil War High Commands. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1. p. 282.

- ↑ "Final Tributes To Montague. Thousands Of Friends Attend His Funeral Services.". The New York Times. August 22, 1878.

The mortal remains of Henry J. Montague were laid to rest yesterday within the quiet precincts of Green-Wood Cemetery....

- ↑ although it had already been published in children's primers in Britain as early as 1813

- ↑ Tripp, Wendell E. (1982). Robert Troup: A Quest for Security in a Turbulent New Nation. Ayer Publishing. p. 322. ISBN 0-405-14074-6. Retrieved 2008-02-02.

Further reading

- Cleveland, Jehemiah (1866). Green-Wood Cemetery: A History from 1838 to 1864. Anderson and Archer.

- Killgannon, Corey (January 30, 2006). "The Ones Who Prepare the Ground for the Last Farewell". The New York Times.

- Bergman, Edward F. (1995). "Green-Wood Cemetery". In Jackson, Kenneth T. The Encyclopedia of New York City. pp. 509–510. ISBN 0300055366.

- Richman, Jeffrey I. (1998). Brooklyn's Green-Wood Cemetery: New York's Buried Treasure.

- Richman, Jeffrey I. (2007). Final Camping Ground: Civil War Veterans at Brooklyn's Green-Wood Cemetery, In Their Own Words. ISBN 0966343530.

- Mosca, Alexandra Kathryn (2008). Green-Wood Cemetery. Images of America: New York.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Green-Wood Cemetery. |

- Official website

- More names of buried persons

- Pictures of Green-Wood

- Seasonal and special event pictures of Green-Wood

- Seeking Room for New Graves at Green-Wood, The New York Times

- Video tour of the catacombs and crypts of Green-Wood Cemetery