Lady Franklin Bay Expedition

The 1881–1884 Lady Franklin Bay Expedition (officially the International Polar Expedition)[1] into the Canadian Arctic was led by Lt. Adolphus Greely and was promoted by the United States Army Signal Corps. Its purpose was threefold: to establish a meteorological-observation station as part of the First International Polar Year,[2] to collect astronomical data, and polar magnetic data. During the expedition, two members of the crew reached a new "Farthest North" record.

The expedition was under the auspices of the Signal Corps at a time when the Corps' Chief Disbursements Officer, Henry W. Howgate, was arrested for embezzlement. However, that did not deter the planning and execution of the voyage.

1881

The expedition was led by Lt. Adolphus Greely of the Fifth United States Cavalry, with astronomer Edward Israel and photographer George W. Rice among the crew of 21 officers and men. They sailed on the ship Proteus and reached St. John's, Newfoundland, in early July 1881.[3] At Godhavn, Greenland, they picked up two Inuit dogsled drivers, as well as physician Dr. Octave Pavy[4] and Mr. Clay[5] who had continued scientific studies instead of returning on Florence with the remainder of the 1880 Howgate Expedition.[6] Proteus arrived without problems at Lady Franklin Bay by August 11,[7] dropped off men and provisions, and left. In the following months, Lt. James Booth Lockwood and Sgt. David Legge Brainard achieved a new "farthest north" record at 83°24′N 40°46′W / 83.400°N 40.767°W,[8] off the north coast of Greenland. Unbeknownst to Greely, the summer had been extraordinarily warm, which led to an underestimation of the difficulties which their relief expeditions would face in reaching Lady Franklin Bay in subsequent years.

1882

By summer of 1882, the men were expecting a supply ship from the south. Neptune, laden with relief supplies, set out in July 1882 but, cut off by ice and weather, Capt. Beebe was forced to turn around prematurely. All he could do was leave some supplies at Smith Sound in August, and the remaining provisions in Newfoundland, with plans for their delivery the following year. On July 20, Dr. Pavy's contract ended, and Pavy announced that he would not renew it, but would continue to attend to the expedition's medical needs. Greely was incensed, and ordered the doctor to turn over all his records and journals. Pavy refused, and Greely placed him under arrest. Pavy was not confined, however Greely claimed he intended to court-martial him when they returned to the United States.[9]

1883

In 1883, new rescue attempts of Proteus, commanded by Lt. Ernest Garlington and Yantic, commanded by Cdr. Frank Wildes, USN, failed, with Proteus being crushed by the ice.

In summer 1883, in accordance with his instructions for the case of two consecutive relief expeditions not reaching Fort Conger, Greely decided to head South with his crew. It had been planned that the relief ships should depot supplies along the Nares Strait, around Cape Sabine and at Littleton Island, if they were unable to reach Fort Conger, which should have made for a comfortable wintering of Greely's men. But with Neptune not even getting that far and Proteus sunk, in reality only a small emergency cache with 40 days worth of supplies had been laid at Cape Sabine by Proteus.

When arriving there in October 1883, the season was too advanced for Greely to either try to brave the Baffin Bay to reach Greenland with his small boats, or to retire to Fort Conger, so he had to winter on the spot.

1884

In 1884, Secretary of the Navy, William E. Chandler, was credited with planning the ensuing rescue effort, commanded by Cdr. Winfield Schley. While four vessels (Bear, Thetis, the British government's Alert, and Loch Garry) made it to Greely's camp on June 22, only seven men had survived the winter.[11][12] The rest had succumbed to starvation, hypothermia, and drowning, and one man, Private Henry, had been shot on Greely's order for repeated theft of food rations.[13]

Homecoming

The surviving members of the expedition were received as heroes. A parade attended by thousands was held in Portsmouth, New Hampshire.[14] It was decided that each of the survivors was to be awarded a promotion in rank by the Army, although Greely reportedly refused.[15]

Allegations of cannibalism

Rumors of cannibalism arose following the return of the bodies of those who did not survive the expedition. On August 14, 1884, a few days after his funeral, the body of Lieutenant Frederick Kislingbury, second in command of the expedition, was exhumed and an autopsy was performed. The finding that flesh had been cut from the bones appeared to confirm the accusation.[16][17][18] Lieutenant Greely denied any knowledge of or official authorization of cannibalism.[13]

References

- ↑ "List of Smithsonian Expeditions, 1878-1917". Smithsonian Institution Archives. May 19, 2003. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ↑ Guttridge, Leonard F. (2000-09-01). "Ghosts of Cape Sabine: the harrowing true story of the Greely expedition". Arctic Institute of North America of the University of Calgary. Retrieved 2008-04-14.

- ↑ Berton, Pierre: The Arctic Grail -- The Quest for the North-West Passage and the North Pole, McClelland and Stewart 1988, ISBN 978-0-7710-1266-2, pp. 438

- ↑ Dr. Octave Pavy

- ↑ Berton (1988), pp. 439

- ↑ Shrady, G. F., & Stedman, T. L. (5 July – 27 December 1884). "Medical Record". 26. New York: William Wood & Co.: 103. OCLC 1757009.

- ↑ Berton (1988), pp. 440

- ↑ Berton (1988), pp. 444

- ↑ Berton (1988), pp. 447-8

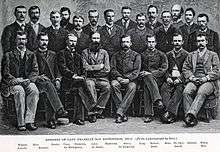

- ↑ Those present are (as numbered on the original print): 1. Commander Winfield S. Schley, USN, commanding officer, Greely Relief Expedition, and of USS Thetis; 2. Lieutenant William H. Emory, Jr., commanding officer of USS Bear; 3. Commander George W. Coffin, USN, commanding officer of Steamer Alert; 4. Lieutenant Emory H. Taunt, USN, Thetis; 5. Lieutenant (Junior Grade) Samuel C. Lemly, USN, Thetis; 6. Lieutenant Freeman H. Crosby, USN, Bear; 7. Lieutenant (Junior Grade) John C. Colwell, USN, Bear; 8. Lieutenant (Junior Grade) Nathaniel R. Usher, USN, Bear; 9. Lieutenant (Junior Grade) Charles J. Badger, USN, Alert; 10. Lieutenant (Junior Grade) Henry J. Hunt, USN, Alert; 11. Ensign Washington I. Chambers, USN, Thetis; 12. Ensign Charles H. Harlow, USN, Thetis; 13. Ensign Lovell K. Reynolds, USN, Bear; 14. Ensign Charles S. McClain, USN, Alert; 15. Ensign Albert A. Ackerman, USN, Alert;16. Chief Engineer George W. Melville, USN, Thetis; 17. Chief Engineer John Lowe, USN, Bear; 18. Passed Assistant Engineer William H. Nauman, USN, Alert; 19. Passed Assistant Surgeon Edward H. Green, USN, Thetis; 20. Passed Assistant Surgeon Howard E. Ames, USN, Bear; 21. Passed Assistant Surgeon Francis S. Nash, USN, Alert; 22. First Lieutenant Adolphus W. Greely, U.S. Army; 23. Private Julius Frederick, U.S. Army; 24. Sergeant David L. Brainard, U.S. Army; 25. Private Henry Bierderbick, U.S. Army; 26. Private Maurice Connell, U.S. Army; 27. Private Francis Long, U.S. Army; 28. Lieutenant Uriel Sebree, USN, Thetis;

- ↑ Guttridge, Leonard F. (2000-09-01). "Ghosts of Cape Sabine: the harrowing true story of the Greely expedition". Arctic Institute of North America of the University of Calgary. Retrieved 2008-04-14.

- ↑ Stein, Stephen K (December 2006). "The Greely Relief Expedition and the New Navy", International Journal of Naval History

- 1 2 "Lieut. Greely Speaks". The New York Times. 14 August 1885. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ↑ "CHEERING ARCTIC HEROES; FORMALLY WELCOMING GREELY AND HIS COMRADES". The New York Times. 5 August 1884. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ↑ "Promotions for Arctic Survivors". The New York Times. 7 August 1884. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ↑ "The Second in Command Lieut. Kislingbury's Mutilated Body Disinterred". The New York Times. 15 August 1884. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ↑ Peck, William F. (1908). History of Rochester and Monroe County, New York. p. 109.

- ↑ "The Shame of the Nation". The New York Times. 13 August 1884. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

Further reading

- Hubank, Roger: North Sentinel Rock Press, 2014. ISBN 978-1940777443. A fictional account of the Lady Franklin Bay Expedition.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lady Franklin Bay Expedition. |

- Report By United States Board of Officers for relief of Lieut Greely and others 1883-1884

- Annual Reports of the Secretary of the Navy Volume 1

- The Greely Arctic Expedition as fully Narrated by Lieut. Greely 1884

- The Rescue of Greely by Winfield Scott Schley 1885

- Collection of the Lady Franklin Bay Expedition 1881-1884 held by The Explorer's Club