Great Central Main Line

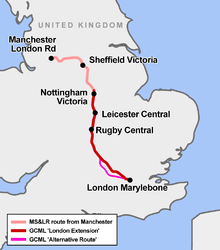

The Great Central Main Line (GCML), also known as the London Extension of the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway (MS&LR), is a former railway line in the United Kingdom. It was opened in 1899 by the Great Central Railway and ran from Sheffield in the North of England, southwards through Nottingham and Leicester to Marylebone Station in London.

The GCML was the last main line railway built in Britain during the Victorian period. It was built by the railway entrepreneur Edward Watkin who aimed to run a high-speed, north-south main line to London. The line was designed to a specification which permitted trains to run at higher speeds; Watkin believed that it would be possible to run direct rail services between Britain and France and had presided over an unsuccessful project to dig a tunnel under the English Channel in the 1880s.

Aside from this ambitious scheme, the GCML operated as a fast trunk route from the North and the East Midlands to London. It was not initially a financial success, only recovering under the leadership of Sam Fay. Although initially planned for long-distance passenger services, in practice the line's most important function became to carry goods traffic, notably coal.

In the 1960s, the line was considered by Dr Beeching as an unnecessary duplication of other lines that served the same places, especially the Midland Main Line and to a lesser extent the West Coast Main Line. Most of the route was closed between 1966 and 1969 under the Beeching axe.

Part of the former main line has been preserved as the Great Central (heritage) Railway between Leicester and Loughborough.

In 2013, the route was suggested by the Labour Party as a cheaper alternative to High Speed 2.[1]

Route

The GCML was very much a strategic line in concept. It was not intended to duplicate the Midland line by serving a great many centres of population. Instead it was intended to link the MS&LR's system stretching across northern England directly to London at as high a speed as possible and with a minimum of stops and connections: thus much of its route ran through sparsely populated countryside.

Starting at Annesley in Nottinghamshire, and running for 92 miles (148 km) in a relatively direct southward route, it left the crowded corridor through Nottingham (and Nottingham Victoria), which was also used by the London and North Western Railway (LNWR), then struck off to its new railway station at Leicester Central, passing Loughborough en route, where it crossed the Midland main line. Four railway companies served Leicester: GCR, Midland, GNR, and LNWR. Avoiding Wigston, the GCR served Lutterworth (the only town on the GCR not to be served by another railway company) before reaching the town of Rugby (at Rugby Central), where it crossed at right-angles over, and did not connect with, the LNWR's West Coast Main Line.

It continued southwards to Woodford Halse, where there was a connection with the East and West Junction Railway (later incorporated into the Stratford-upon-Avon and Midland Junction Railway), and slightly further south the GCR branch to the Great Western Railway station at Banbury. From Woodford Halse the route continued approximately south-east via Brackley to Calvert and Quainton Road, where Great Central trains joined the Metropolitan Railway (later Metropolitan and Great Central Joint Railway) via Aylesbury into London.

Partly because of disagreements with the Metropolitan Railway (MetR) over use of their tracks at the southern end of the route, the company built the Great Western and Great Central Joint Railway joint line (1906) from Grendon Underwood to Ashendon Junction, by-passing the greater part of the MetR's tracks.

Apart from a small freight branch to Gotham between Nottingham and Loughborough, and the "Alternative Route" link added later (1906), these were the only branch lines from the London extension. The line crossed several other railways but had few junctions with them.

North of Sheffield, express trains on the London extension made use of the pre-existing MS&LR trans-Pennine main line, the Woodhead Line (now also closed) to give access to Manchester London Road (now named Manchester Piccadilly).

History

Reasons for construction

In 1864 Sir Edward Watkin took over directorship of the Manchester, Sheffield & Lincolnshire Railway (MS&LR). He had grand ambitions for the company: he had plans to transform it from a provincial middle-of-the-road railway company into a major national player. He grew tired of handing over potentially lucrative London-bound traffic to rivals, and, after several unsuccessful attempts in the 1870s to co-build a line to London with other companies, decided that the MS&LR needed to create its own route to the capital. Construction of the GCML was commissioned to enable Watkin's railway company to operate its own direct express route to London independently of — and in competition with — rival railway companies.[2]

At the time many people questioned the wisdom of building the line, as all the significant population centres which the line traversed were already served by other companies. However, Watkin defended it by arguing that growth in traffic would justify the new line.[3]

Watkin was an ambitious visionary; as well as running an independent trunk route into London, he also aspired to connect his larger railway empire to the rail network of France and had even begun a project to dig a channel tunnel under the English Channel,[4] a scheme vetoed in 1882 by the British Parliament for fear of military invasion by France.[5]

Watkin's Great Central Main Line was designed to a continental European loading gauge, more generous than the usual specification on British railway lines, and it is thought that Watkin's aim was to construct a line which, when connected to a future channel tunnel, would be able to accommodate larger continental rolling stock.[6][7][8]

Construction of the line

In the 1890s the MS&LR set about building its own line, having received Parliamentary approval on 28 March 1893,[9] for the London Extension. The Bill nearly failed due to opposition from cricketers at the Marylebone Cricket Club in London through which the line would pass.[10] However it was agreed to put the line through a tunnel passing under the grounds.[3] The first sod of the new railway was cut at Alpha Road, St John’s Wood, London, on 13 November 1894 by Countess Wharncliffe, wife of 1st Earl of Wharncliffe, the Chairman of the Board.[11]

The new line, 92 miles (148 km) long started at Annesley in Nottinghamshire and ran to Quainton Road in Buckinghamshire.[12]:32 From here, the route followed the existing Metropolitan Railway (MetR) Extension (which became joint MetR/GCR owned) as far as Harrow and thence along the (GCR owned) final section to Marylebone.

Construction of the route involved some major engineering works, including three new major city-centre stations (Nottingham Victoria, Leicester Central and Marylebone) along with many smaller ones. A number of new viaducts were constructed for the line including the 21-arch Brackley Viaduct, and viaducts at Braunston, Staverton and Catesby in Northamptonshire, one was built over the River Soar, along with two over Swithland Reservoir in Leicestershire, and one over the River Trent near Nottingham. Several tunnels had to be built, the longest of which was the 2,997 yards (2,740 m) Catesby Tunnel. Many miles of cuttings and embankments were also built.[13]

The construction of the railway through Nottingham and the station involved heavy earthworks with 6,750 feet (2,060 m) of tunnelling and almost 1 mile (1.6 km) of viaduct. The site for Nottingham Victoria railway station required the demolition of 1,300 houses, 20 public houses[12]:132 and the clearing of a cutting from which 600,000 cubic yards (460,000 m3) of sandstone were removed.[12]:132 The purchase of the land cost £473,000[12]:132 (equivalent to £49,270,000 in 2015),[14] and the construction of the station brought the sum to over £1,000,000.

The original estimated cost for the construction of the line was £3,132,155, however in the event it cost £11,500,000 (equivalent to £1,167,470,000 in 2015),[14] nearly four times the original estimate.[13]

Features of the line were:

- The line was engineered to very high standards: a ruling gradient of 1 in 176 (5.7 ‰)[10] (exceeded in only a few locations on the London extension) was employed; curves of a minimum radius of 1 mile (1.6 km) (except in city areas) were used;[10] and there was only one level crossing between Sheffield Victoria and London Marylebone (at Beighton, still in use).

- The standardised design of stations, almost all of which were built to an "island platform" design with one platform between the two tracks instead of two at each side. This was so that the tracks only needed to be moved further away from the platform if continental trains were to traverse the line, rather than wholesale redesign of stations. It would also aid any future plans to add extra tracks (as was done in several locations).

The line was formally opened by Charles Ritchie, 1st Baron Ritchie of Dundee, President of the Board of Trade on 9 March 1899.[15] Three special corridor trains, forming part of the new rolling stock constructed for the new line, were run from Manchester, Sheffield and Nottingham to the terminus at Marylebone for the inaugural ceremony. A lunch for nearly 300 guests was provided, and then the trains made the return trip.

Public passenger services began on 15 March 1899,[12]:132 and for goods traffic on 11 April 1899. Shortly before the opening of the new line, the MS&LR changed its name to the grander-sounding "Great Central Railway" (GCR) to reflect its new-found national ambitions.[16]

The London extension was the last mainline railway line to be built in Britain until section one of High Speed 1 opened in 2003. It was also the shortest-lived intercity railway line.

Traffic on the London extension

Passenger

The London Extension's main competitor was the Midland Railway which had served the route between London, the East Midlands and Sheffield since the 1860s on its Midland Main Line. Traffic was slow to establish itself on the new line, passenger traffic especially so. Enticing customers away from the established lines into London was more difficult than the GCR's builders had hoped. However, there was some success in appealing to higher-class 'business' travellers in providing high-speed luxurious trains, promoted by the jingle 'Rapid Travel in Luxury'. These were in a way the first long-distance commuter trains. The Great Central also became important for cross-country trains, which took advantage of its connections to other lines.[17]

Nevertheless, in the late-1930s heyday of fast long-distance passenger steam trains, there were six crack expresses a day from Marylebone to Sheffield, calling at Leicester and Nottingham, and going forward to Manchester. Some of these achieved a London-Sheffield timing of 3 hours and 6 minutes in 1939, making them fully competitive with the rival Midland service out of St Pancras as far as journey time was concerned.[18]

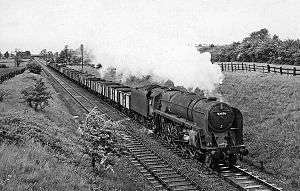

Freight

Freight traffic grew healthily and became the lifeblood of the line, the staples being coal, iron ore, steel, and fish and banana trains. The connection with the Stratford-upon-Avon and Midland Junction Railway at Woodford Halse proved strategically important for freight on the route. Another major centre for freight was at Annesley.[19]

Rundown and closure

The First World War, and the hostile European political climate which followed, ended any possibility of a Channel Tunnel being constructed within the GCR's lifetime. The various Channel Tunnel schemes, including one in 1883 which prompted Sir Edward Watkin and the MS&LR to construct the London extension, foundered on the fear of French invasion. Further work in the 1920s was again vetoed for similar reasons. In the 1923 Grouping the Great Central Railway was merged into the London and North Eastern Railway, which in 1948 was nationalised along with the rest of Britain's railway network. The Great Central thrived in the early years of nationalisation. However, from the late 1950s onwards the freight traffic upon which the line relied started to decline, and the GCR route was largely neglected as other railway lines were thought to be more important.

It was designated a duplicate of the Midland Main Line and in 1958 transferred from the management of the Eastern Region to the London Midland Region, whose management still had loyalties to former companies (Midland/LMS) and against their rivals GCR/LNER.

In January 1960, express passenger services from London to Sheffield and Manchester were discontinued, leaving only three "semi-fast" London-Nottingham trains per day. In March 1963 local trains on many parts of the route were cancelled and many rural local stations were closed. However, at this time it was still hoped that better use of the route could be made for parcels and goods traffic.[20]

In the 1960s Beeching era, Dr Beeching decided that the London to northern England route was already well served by other lines, to which most of the traffic on the GCR could be diverted. Closure came to be seen as inevitable.

The sections between Rugby and Aylesbury and between Nottingham and Sheffield were closed in 1966, leaving only an unconnected stub between Rugby and Nottingham, on which a skeleton shuttle service operated. This last stretch was closed to passenger services in May 1969. Goods trains continued to run on the London Extension between Nottingham and East Leake until 1973, and continue to run between Loughborough and East Leake to this day.

The closure of the GCR was the largest single closure of the Beeching era, and one of the most controversial. In a letter published in The Daily Telegraph on 28 September 1965, Denis Anthony Brian Butler, 9th Earl of Lanesborough, a peer and railway supporter, wrote:

| “ | [Among] the main lines in the process of closure, surely the prize for idiotic policy must go to the destruction of the until recently most profitable railway per ton of freight and per passenger carried in the whole British Railways system, as shown by their own operating statistics. These figures were presented to monthly management meetings until the 1950s, when they were suppressed as "unnecessary", but one suspects really "inconvenient" for those proposing Beeching type policies of unnecessarily severe contraction of services [...] This railway is of course the Great Central forming a direct Continental loading gauge route from Sheffield and the North to the Thames valley and London for Dover and France [...].[21] | ” |

Recent history

A new company founded in 1991, Central Railway Ltd, proposed to re-open the GCR largely as a freight link following completion of the Channel Tunnel rail link. These proposals faced financial, environmental and social difficulties and were rejected by Parliament twice.[22]

Remaining infrastructure

The trackbed of the 40-mile stretch of main line between Calvert and Rugby, closed in 1966, is still intact except for a missing viaduct at Brackley and Willoughby. Proposals for its reopening as part of one scheme or another are made from time to time.[23]

Frequent passenger services run over the joint line between London Marylebone and Aylesbury Vale Parkway, and also between Marylebone and High Wycombe (continuing northwards to Princes Risborough, Bicester North, Banbury and Birmingham Snow Hill). Currently, both these groups of services are operated by Chiltern Railways. Strictly speaking, neither of these routes is specifically of GCR heritage, although the line between Neasden South Junction and Northolt Junction was built, maintained and run by the GCR and is still in use today for all Chiltern Main Line services.

A short extension of Chiltern passenger services to a new Aylesbury Vale Parkway railway station on the Aylesbury-Bicester main road opened on 14 December 2008.[24] There are also heritage diesel shuttle services on the May Bank Holiday and August Bank Holiday weekends between Aylesbury and Quainton Road stations, the latter serving the Buckinghamshire Railway Centre.

In November 2011 HM Government allocated funding for reopening of the section between Bicester and Bletchley (via Claydon Junction), and between Aylesbury Vale Parkway and Claydon Junction, as part of the East West Rail Link scheme,[25] which could see passenger services operating between Reading and Milton Keynes Central (via Oxford) and between London (Marylebone) and Milton Keynes (via Aylesbury).

Currently, this stretch of route is used for freight consisting of binliner (containerised domestic waste) and spoil trains going to the Calvert Waste Facility (landfill) site at Calvert just south of Calvert station. Four container trains each day use the site, originating from: Brentford; Cricklewood; and Northolt. There was also a daily train from Bath and Bristol (known as the "Avon Binliner") until April 2011. The containers, each of which contains 14 tons of waste, are unloaded at the transfer station onto lorries awaiting alongside which then transport the waste to the landfill site.[26] The site, dating from 1977 and now one of the largest in the country, stretches to 106 hectares and partly reuses the clay pits dug out by Calvert Brickworks which closed in 1991.[27]

The Main Line Preservation Group was established in 1968, to preserve part of the remaining section of the Great Central main line. The group was reformed, in 1971, as Main Line Steam Trust Limited and the group's original ambitions were trimmed to exclude the section north of Loughborough. Restoration work on the line between Loughborough Central and the northern outskirts of Leicester commenced and, by 1973, Steam train services were operated under the supervision of a British Railways Inspector.[28] In 1976 operations were transferred to Great Central Railway (1976) Limited a company that, as Great Central Railway PLC, remains active to this day. Additionally, a preserved single-track section under the auspices of the Nottingham Transport Heritage Centre at Ruddington is operated with occasional services run by Great Central Railway (Nottingham). There are plans to relink this section to the adjacent mainline section.[29]

North of Ruddington, and as far as Nottingham, sections of the GCML right of way are used by the Nottingham Express Transit (NET), Nottingham's second generation tramway. The first section is north from Ruddington Lane tram stop as far as the River Trent, used by the 2015-opened line 2 of NET. North of the river the Great Central route was eliminated by housing development in the 1970s, and the tramway uses a different route across the river and north to Nottingham railway station (the former Midland station). The GCML crossed above this on a bridge, and NET uses the same alignment to provide a tram stop at the station before transitioning back to the city streets. North of here the GCML route is blocked by the Victoria shopping centre, built on the site of the GCR's Nottingham station.[30]

Sections of the GCML around Rotherham are open for passenger and freight traffic, indeed a new station was built there in the 1980s using the Great Central lines which were closer to the town centre than the former Midland Railway station. Commuter EMU trains run from Hadfield to Manchester via Glossop. These are modern trains using 25 kV overhead wires that were installed to replace the 1500 V system. Daily steel trains run from Sheffield to Deepcar where they feed the nearby Stocksbridge Steelworks[31][32] owned by Tata Group.

Plans

High Speed 2

In March 2010 the government announced plans for a future high-speed railway between London and Birmingham that would re-use about 12 miles of the GCR route. The proposed line would parallel the current Aylesbury line (former Met/GCR joint) corridor and then continue alongside the GCR line between Quainton Road and Calvert. From there it would roughly follow the disused but still extant GCR trackbed via Finmere as far as Mixbury before diverging on a new alignment towards Birmingham.

East West Rail Link

It was announced in November 2011 that HM Government had allocated funding to re-open the section of track from Aylesbury Parkway to a re-opened Varsity Line as part of the proposed East West Rail Link. The line is due to be opened in 2019.[33]

Aylesbury to Rugby

Chiltern Railways did have a long-term plan to reopen the Great Central Main Line north of Aylesbury as far as Rugby[23] and onward at a later stage to Leicester. However, in 2013 Chiltern Railways stated that the plan is "no longer active".[34]

Freight Reopening

In August 2017, the English Regional Transport Association (a voluntary lobby group) proposed that the line between Calvert and Rugby be reopened using a continental loading gauge, the same as that previously used by the Great Central Railway. The proposal includes a new stretch bypassing the western side of Rugby and would join the West Coast Main Line.[35] A petition online by ERTA has proposed the line should be reopened all the way to Manchester as it would increase capacity on the network with a loop at Buckingham and new stations at Daventry & Brackley with a link to the East West Rail Link at Claydon. New sections of track will be required in some areas if this does happen.[36]

Re-opening

The Labour MP for Luton North, Kelvin Hopkins, proposed the re-opening of the GCR as cheaper alternative to HS2.[1] Hopkins had advocated re-opening the GCR as Central Railway – a freight line for a direct container transport connection between continental Europe and northern England – in 2002.[37]

References

- 1 2 Ross, Tim; Gilligan, Andrew (27 October 2013). "HS2: Labour to examine cheaper rival plan". The Sunday Telegraph. London.

- ↑ Healy 1987, pp. 24–25.

- 1 2 Healy 1987, p. 27.

- ↑ Goffin, Magdalen (2005). "4. The Watkin path". The Watkin path : an approach to belief. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press. pp. 23–25. ISBN 9781845191283. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ↑ Hadfield-Amkhan, Amelia (2010). "4. The 1882 channel Tunnel Crisis". British foreign policy, national identity, and neoclassical realism. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 73–76. ISBN 9781442205468.

- ↑ Sharpe, Brian (2009). The Flying Scotsman : the legend lives on. Barnsley: Wharncliffe. p. 100. ISBN 9781845630904. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ↑ Guise, Richard (2013). A wiggly way through England. Richard Guise. p. 163. ISBN 9780954558741. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ↑ Brandon, David; Brooke, Alan (2010). Shadows in the Steam the haunted railways of Britain. Stroud: History Press. pp. 49–50. ISBN 9780752462301. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ↑ "Doings of Parliament. House of Lords". Shields Daily Gazette. British Newspaper Archive. 29 March 1893. Retrieved 23 July 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive. (Subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 3 "The Manchester, Sheffield, And Lincolnshire Extension. London’s New Terminus". Bucks Herald. British Newspaper Archive. 24 November 1894. Retrieved 23 July 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "The New Line to London. Cutting the First Sod". Nottingham Evening Post. British Newspaper Archive. 14 November 1894. Retrieved 23 July 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive. (Subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 3 4 5 Leleux, Robin (1976). A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain. Volume 9 The East Midlands. David & Charles. Newton Abbot. ISBN 0715371657.

- 1 2 Healy 1987, pp. 24–53.

- 1 2 UK Consumer Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Gregory Clark (2016), "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)", MeasuringWorth.com.

- ↑ "Opening of the London Extension. Speech by Mr. C. T. Ritchie". Sheffield Daily Telegraph. British Newspaper Archive. 10 March 1899. Retrieved 23 July 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Healy 1987, pp. 54–55.

- ↑ Healy 1987, pp. 78–86.

- ↑ Cook's Continental Time-Table, London, August 1939, pp. 90, 108.

- ↑ Healy 1987, pp. 90-105.

- ↑ "The Great Central", Trains Illustrated, London, February 1960, p.68.

- ↑ The Daily Telegraph, London, 28 September 1965; Quoted in: Buckman, J., "The Steyning Line and its closure", S.B. Publications, 2002, p. 7.

- ↑ Central Railway Ltd, Resources, 2006.

- 1 2 "Bid To Reopen Central Railway To Passengers". 10 August 2000.

- ↑ "Aylesbury Vale Parkway fully open in June". The Bucks Herald. Aylesbury. 14 April 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- ↑ "Autumn statement backs investment in east west rail". East West Rail Consortium. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- ↑ Calvert waste transfer station

- ↑ Calvert Landfill Site

- ↑ Main Line No. 11, published by Main Line Steam Trust Limited

- ↑

- ↑ Skelsey, Geoffrey (2015). Nottingham's growing tramway - Building on NET's success. LRTA. ISBN 978-0-948106-49-1.

- ↑ Shannon, Paul (September 2014). "British Freight Today - Metals". The Railway Magazine. Vol. 161 no. 1362. p. 24.

- ↑ Shannon, Paul (17 February 2016). "Freight steels itself for a fresh challenge". Rail Magazine. No. 794. p. 70. ISSN 0953-4563.

- ↑ "Disappointment as East West Rail delayed by two years" (Press release). Bucks Herald. 31 March 2014. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ↑ "Chiltern Railways Twitter Feed". 25 February 2013.

- ↑ RAIL Issue 832, p.37

- ↑ "PressReader.com - Connecting People Through News". www.pressreader.com. Retrieved 2017-08-11.

- ↑ "Hansard 11 Jun 2002 : Column 185WH Central Railway". 11 June 2002.

Sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Great Central Main Line. |

- Dow, George (1962). Great Central. 2: Domination of Watkin, 1864–1899. Shepperton: Ian Allan. OCLC 655514941.

- Healy, John (1987). Echoes of the Great Central. Greenwich Editions. ISBN 0-86288-076-9.

External links

- "The Last Main Line". Railway Archive. Transport Archive.