Grandes Heures of Anne of Brittany

The Grandes Heures of Anne of Brittany (Les Grandes Heures d'Anne de Bretagne in French) is a book of hours, commissioned by Anne of Brittany, Queen of France to two kings in succession, and illuminated in Tours or perhaps Paris by Jean Bourdichon between 1503 and 1508. It has been described by John Harthan as "one of the most magnificent Books of Hours ever made",[1] and is now in the Bibliothèque nationale de France as Ms lat. 9474. It has 49 full-page miniatures in a Renaissance style, and more than 300 pages have large borders illustrated with a careful depiction of, usually, a single species of plant.

Description

The book is large for a book of hours at 30.5 cm by 20 cm, and consists of 476 pages including 49 full-page miniatures, 12 calendar pages with genre scenes of the months of the year, two pages of Anne's heraldic devices, and 337 pages with illuminated borders showing flowers and other plants.[2] The full-page miniatures have large figures in an advanced Renaissance style for France at this date, drawing on both Italian and Flemish painting, and with well-developed perspective. There are gold highlights on the figures, a technique taken from Bourdichon's master Jean Fouquet, and the miniatures are framed with imitation gilded wood picture frames of the type found in Early Netherlandish painting, a style Bourdichon used in some other miniatures.[3] Similar frames surround the miniatures of the Sforza Hours, begun in Italy in the 1490s. Outside the frames the edges of these pages are painted plain black. Some landscape backgrounds suggest a knowledge of the sfumato style of Leonardo da Vinci.[4] In particular specific borrowings from the architecture of Bramante and the painting of Perugino suggest that Bourdichon may have made an unrecorded visit to Italy.[5]

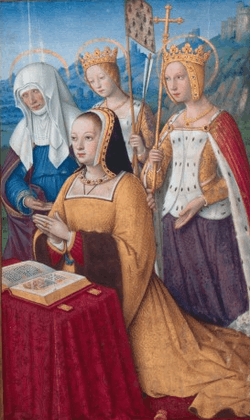

There is a donor portrait of Anne at prayer, presented by her patron saints to the dead Christ held by the Virgin Mary in a Pietà on the facing page, the Virgin meeting Anne's gaze.[6] Night-scenes include a famous Annunciation to the Shepherds and the Nativity.[7] Despite the general "sweetness of Bourdichon's style",[8] the work contains gruesome images of the mass martyrdoms of Saint Ursula's eleven thousand virgin companions and the Theban Legion, though rather characteristically both show moments after the action and contain relatively little movement. Scenes from the Life of Christ and that of the Virgin are depicted as well as a number of portraits and scenes of saints. F. 197v has the rare scene of the Virgin Mary being taught how to read by Saint Anne, who is seated on a dais like a medieval professor.

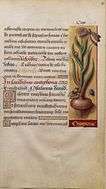

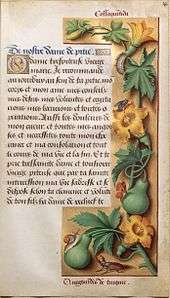

The book is also remarkable for its realistic representations of 337 plants in the borders that most text pages are given.[9] There are flowers, cultivated and wild, shrubs, some trees and among the plants a wide variety of insects and small animals of the countryside. The plants include Cannabis sativa on f. 90v, and the major cereal crops of the day on ff. 94–96. The insects represented are butterflies and moths, dragonflies, grasshoppers, caterpillars, beetles, flies, carpenter bees, crickets, earwigs, bees and beetles. The small animals represented are snakes, lizards, slow worms, frogs, turtles, squirrels, snails, rabbits, monkeys and spiders. The style borrows from the elaborate and realistic borders of natural life developed in the preceding decades by Flemish illuminators, but unlike them Bourdichon generally treats only one species on a page, and often shows roots and bulbs, and labels each page with the plant's name in Latin and French, in the manner of a florilegium or a herbal (a book on medicinal plants).[10] In most pages the border is a single panel to the outside of the text, but in others it surrounds the text on all four sides. The plants are shown as if laid out on a plain coloured surface, upon which they cast a shadow. In 1894 Giulio Camus wrote an account of the plants in the work, and a full modern facsimile was published in 2008. There are 395 images from the book available online through the BnF.[11]

Commission

Anne of Brittany was the last independent ruler of Brittany, inheriting the Duchy as a girl of twelve in 1488, and securing her inheritance was a crucial matter for both the House of Habsburg and the French Crown. She first conducted a proxy marriage with Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor, then still heir to the Empire, who had already acquired the Duchy of Burgundy for his son by his first wife Mary of Burgundy (who like Anne's father had died in a riding accident). But there was a recent treaty between Brittany and France requiring French consent to Anne's marriage, and this had not been obtained. After a French invasion, the marriage was swiftly annulled and one arranged with Charles VIII of France. All their four children died as infants, so when Charles died in 1498, logic dictated a marriage with his cousin and successor, Louis XII, once he had annulled his marriage with Anne's sister-in-law Jeanne de France. After many more pregnancies and stillborn children, at her death in 1514 Anne left two daughters, of whom Claude married François I, the cousin who succeeded to the throne.[12]

According to a letter from the queen written in March 1508, Jean Bourdichon, who was one of the main artists regularly working for the court, was paid the sum of 1500 livres tournois in the form of 600 écus, although it seems the payment was not made for several years.[13] In all, four books of hours belonging to Anne survive, including the Très Petites Heures d'Anne de Bretagne (BnF Ms nouv. acq. 3120) of about 1498, another with the same name in the Morgan Library in New York (M. 50), and the Petites Heures d'Anne de Bretagne (BnF Ms nouv. acq. 3027) of around 1503.[14] Prayers like Obsecro te, which are written in Latin, contain words such as pronouns that indicate the gender of the supplicant. More often than not, the words indicate that the supplicant is male, even if the supplicant is female, suggesting that the prayer books were intended to be passed on as an heirloom that males would be able to use. This is true of the Obsecro te in the Grandes Heures of Anne of Brittany.[15] After Anne's death the book remained in the hands of the French royal family until the Revolution, and then passed to the government.

In art history

The book comes very late in the history of the illuminated manuscript, and the conception of the full-page miniatures as resembling a series of individual panel paintings, complete with frames, has seemed to many art historians a prophecy of the direction art was to take, and something of an abdication of the distinct needs of book illustration. Anthony Blunt noted that "Many of his designs – for instance the 'St Sebastian' – look in reproduction like altarpieces rather than miniatures; and to this extent his art represents the decay of true illumination".[16] However, royalty and the grandest other patrons continued to commission manuscripts for several further decades, and in some cases well after that, and the miniatures of the Grandes Heures are integrated with the texts of the book in the traditional ways. For example, the borders opposite miniatures are often co-ordinated with them in terms of colour.[17] By Anne's day printing was well established, with Paris as one of Europe's leading centres, and she also patronized printed books and their authors.[18]

Gallery

- The Flight into Egypt, f. 76v

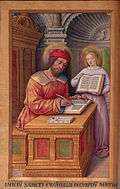

Saint Matthew the Evangelist, f. 87

Saint Matthew the Evangelist, f. 87 The martyrdom of the Theban Legion, f. 177v

The martyrdom of the Theban Legion, f. 177v The Holy Trinity, f. 155v

The Holy Trinity, f. 155v- The floral borders opposite the shepherds, f. 69, with Solanum dulcamara

Onion, f. 143

Onion, f. 143 Cucurbita pepo subsp. texana, f. 161[19]

Cucurbita pepo subsp. texana, f. 161[19]

Notes

- ↑ Harthan, 128. The name means "The Large Hours" as opposed to her "Small Hours" and "Very Small Hours" (see below); the mixed French and English of the name is usual in English sources.

- ↑ Walther & Wolf, 409

- ↑ Harthan, 128; Blunt, 18; Walther & Wolf, 409; for another example, see File:Bnf059.jpg from Jean Marot, Le Voyage de Gênes (Voyage to Genoa), Tours, around 1508, BnF MS Fr. 5091

- ↑ Harthan, 128; Walther & Wolf, 409

- ↑ Blunt, 18–19

- ↑ Harthan, 128

- ↑ Harthan, 132; Walther & Wolf, 408–409

- ↑ Harthan, 128

- ↑ Harthan, 133; Walther & Wolf, 409

- ↑ Harthan, 133; Blunt, 18

- ↑ See external links for the facsimile and the online images

- ↑ Harthan, 128–129

- ↑ Harthan, 37

- ↑ Walther & Wolf, 410–411

- ↑ Harthan, 85; this may have been to encourage the use of the books as heirlooms that would be used by descendents, including males.

- ↑ Blunt, 19; Harthan, 132; Walther & Wolf, 410

- ↑ Harthan, 132; Walther & Wolf, 410

- ↑ See Brown in further reading, throughout.

- ↑ Paris, Harry S.; Daunay, Marie-Christine; Pitrat, Michel; Janick, Jules (July 2006). "First Known Image of Cucurbita in Europe, 1503–1508". Annals of Botany. 98 (1): 41–47. PMC 2803533

. PMID 16687431. doi:10.1093/aob/mcl082.

. PMID 16687431. doi:10.1093/aob/mcl082.

References

- Blunt, Anthony, Art and Architecture in France, 1500–1700, 2nd edn 1957, Penguin

- Harthan, John, The Book of Hours, 1977, Thomas Y Crowell Company, New York, ISBN 0690016549

- Walther, Ingo F. and Wolf, Norbert, Masterpieces of Illumination (Codices Illustres), 2005, Taschen, Köln; ISBN 382284750X

Further reading

- Brown, Cynthia Jane, The Queen's Library: image-making at the court of Anne of Brittany, 1477–1514, 2010, University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 0812242823, 9780812242829, google books

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Grandes Heures d'Anne de Bretagne. |

- BnF, Mandragore database enter "Latin 9474" in "Cote" box for 395 "Images" (in French)

- Digital facsimile of the entire manuscript on Gallica

- Le Monde