Grand Isle, Louisiana

| Grand Isle, Louisiana | ||

|---|---|---|

| Town | ||

|

Lighthouse Christian Fellowship Church in Grand Isle | ||

| ||

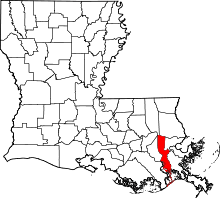

Location of Grand Isle in Jefferson Parish, Louisiana. | ||

.svg.png) Location of Louisiana in the United States | ||

| Coordinates: 29°14′N 90°00′W / 29.233°N 90.000°WCoordinates: 29°14′N 90°00′W / 29.233°N 90.000°W[1] | ||

| Country | United States | |

| State | Louisiana | |

| Parish | Jefferson | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | David Camardelle (D) | |

| Area[2] | ||

| • Total | 8.17 sq mi (21.15 km2) | |

| • Land | 6.40 sq mi (16.57 km2) | |

| • Water | 1.77 sq mi (4.58 km2) | |

| Elevation[1] | 7 ft (2 m) | |

| Population (2010) | ||

| • Total | 1,296 | |

| • Estimate (2016)[3] | 1,416 | |

| • Density | 221.35/sq mi (85.47/km2) | |

| Time zone | CST (UTC-6) | |

| • Summer (DST) | CDT (UTC-5) | |

| Area code(s) | 985 | |

| FIPS code | 22-30830 | |

| Website |

www | |

Grand Isle (French: Grande-Île) is a town in Jefferson Parish, Louisiana, located on a barrier island of the same name in the Gulf of Mexico. The island is at the mouth of Barataria Bay where it meets the gulf. As of the 2010 census, the town's resident population was 1,296, down from 1,541 at the 2000 census; during summers, the population including tourists and seasonal residents sometimes increases to over 20,000. Grand Isle is statistically part of the New Orleans−Metairie−Kenner Metropolitan Statistical Area, though it is not connected to New Orleans' continuous urbanized area.

Grand Isle's main street is the seaside start of Louisiana Highway 1 (LA 1), which stretches 436.2 miles (702.0 km) away to the northwest corner of the state, ending near Shreveport. LA 1's automobile causeway at the west end of the island is the only land access to or from Grand Isle.

Direct access to Grand Isle's seat of parish government is 95 miles (153 km) away in suburban Jefferson Parish, which leaves the town somewhat politically isolated.

History

Grand Isle has been repeatedly pummeled by hurricanes through its history. On average, Grand Isle has been affected by tropical storms or hurricanes every 2.68 years (since 1877), with direct hits on average every 7.88 years.[4] Some of the more severe are listed here.

In 1860 a 6-foot (2 m) storm surge and great winds resulted in the total devastation of the island. In the 1893 Atlantic hurricane season Grand Isle was devastated by a 16-foot (5 m) storm surge. In the 1909 Atlantic hurricane season the island was hit with a second 16-foot (5 m) storm surge. A Category 4 hurricane devastated Grand Isle on 29 September during the 1915 Atlantic hurricane season. Grand Isle was hit by a 3.6-foot (1.1 m) storm surge on 22 August during the 1947 Atlantic hurricane season. In 1956 Hurricane Flossy damaged the island.

Hurricane Betsy in September 1965 and Tropical Storm Frances in 1998 put the entire island under water. On 26 September 2002, Grand Isle was hit by Hurricane Isidore, soon followed by Hurricane Lili passing to the west of the island, causing significant damage. Hurricane Cindy scored a direct hit on Grand Isle on July 5, 2005. Even though damage was essentially limited to power outages and beach erosion, the storm's strength still caught residents by surprise.

Hurricane Katrina pounded Grand Isle for two days, August 28–29, 2005, destroying or damaging homes and camps along the entire island. Katrina's surge reached 5 ft (1.5 m) at Grand Isle. Large waves severely damaged the only bridge linking Grand Isle to the mainland.[5] A news report published less than two days after the hurricane hit falsely noted, however, that the area had been completely destroyed, reporting a scenario similar to that which befell Last Island in 1856.[6] Less than a month later, Grand Isle was further affected by Hurricane Rita. By mid October, a number of businesses were again open on the island.

Hurricane Gustav reached shore west of the island on September 1, 2008, at 9 am CDT, and hit it with a measured wind speed of 105 mph (169 km/h). It was one of the few locations in Louisiana affected while the storm was still classified as major hurricane. While both storms' eyes passed the island at similar distances, Katrina's eastern passing caused greatest damage on the bay side of island. The Gustav surge that washed over the island caused less damage than Katrina, in part due to the most vulnerable structures having already been destroyed by Katrina. Current construction codes prevented the rebuilding of such vulnerable structures. Barataria Pass water levels peaked at 5 ft (1.5 m) above recent high tide. Homes along Louisiana Highway 1 had 2 ft (0.6 m) of water below them. Large sections of levee/dunes were washed onto the highway.

Hurricane Ike passed far south of the island on September 11, 2008, while crews worked to restore power and repair the levee/dune damage caused by Gustav. Some sections of LA 1 west of the island were covered by 1 ft (0.3 m) of water. Wind gusts reached 50 mph (80 km/h) and Barataria Pass water levels reached 3 ft (0.9 m) above recent high tide while Ike was 200 miles (320 km) away.

Geography

Grand Isle is located at 29°14′N 90°0′W / 29.233°N 90.000°W (29.233, −90.000) which corresponds to 54 miles due south of New Orleans, Louisiana. According to the United States Census Bureau, the town covered a total area of 7.8 square miles (20 km2), where 6.1 square miles (16 km2) is land, and 1.7 square miles (4.4 km2) (20.88%) is water.

Climate

| Climate data for Grand Isle, Louisiana | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 83 (28) |

82 (28) |

86 (30) |

91 (33) |

95 (35) |

99 (37) |

100 (38) |

100 (38) |

97 (36) |

94 (34) |

86 (30) |

82 (28) |

100 (38) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 63 (17) |

65 (18) |

71 (22) |

77 (25) |

83 (28) |

88 (31) |

89 (32) |

90 (32) |

86 (30) |

80 (27) |

72 (22) |

65 (18) |

77.4 (25.2) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 44 (7) |

48 (9) |

54 (12) |

60 (16) |

68 (20) |

74 (23) |

75 (24) |

75 (24) |

72 (22) |

62 (17) |

54 (12) |

46 (8) |

61 (16.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 14 (−10) |

12 (−11) |

16 (−9) |

35 (2) |

48 (9) |

50 (10) |

65 (18) |

62 (17) |

52 (11) |

34 (1) |

24 (−4) |

10 (−12) |

10 (−12) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 5.1 (130) |

4.9 (124) |

4.7 (119) |

3.2 (81) |

4.5 (114) |

7.2 (183) |

8.0 (203) |

7.6 (193) |

6.2 (157) |

4.7 (119) |

3.4 (86) |

4.7 (119) |

64.2 (1,628) |

| Source: The Weather Channel (Monthly Averages) [7] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1960 | 2,074 | — | |

| 1970 | 2,236 | 7.8% | |

| 1980 | 1,982 | −11.4% | |

| 1990 | 1,455 | −26.6% | |

| 2000 | 1,541 | 5.9% | |

| 2010 | 1,296 | −15.9% | |

| Est. 2016 | 1,416 | [3] | 9.3% |

At the census[9] of 2000, 1,541 people, 622 households, and 436 families lived in the town. The population density was 251.1 inhabitants per square mile (97.0/km2). There were 1,875 housing units at an average density of 305.6 per square mile (118.0/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 96.04% White, 2.27% Native American, 0.19% African American, 0.19% Asian, 0.39% from other races, and 0.91% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.49% of the population.

There were 622 households out of which 29.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 54.2% were married couples living together, 8.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 29.9% were non-families. 24.0% of all households were made up of individuals and 9.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.46 and the average family size was 2.89.

In the town, the population was spread out with 23.7% under the age of 18, 7.9% from 18 to 24, 26.3% from 25 to 44, 28.9% from 45 to 64, and 13.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 40 years. For every 100 females there were 104.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 108.1 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $33,548, and the median income for a family was $35,517. Males had a median income of $34,000 versus $19,333 for females. The per capita income for the town was $18,330. About 9.1% of families and 13.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 14.3% of those under age 18 and 12.9% of those age 65 or over.

Education

Grand Isle, like all locations in Jefferson Parish, is served by the Jefferson Parish Public Schools. The Grand Isle School serves pre-kindergarten through 12th grade.

Grand Isle Library is a small public library responding to the needs of local residents and visitors. The new Grand Isle Library opened on Wednesday, November 14, 2012.[10]

Arts and culture

Fishing is an important part of Grand Isle's culture. The island is a premier destination for avid fishermen as anglers adore the more than 280 species of fish in the surrounding waters. In 1928, the annual Grand Isle Tarpon Rodeo, fishing tournament, was established on the island and is now one of the premier salt water fishing rodeos in the United States. The Cajun rodeo draws over 15,000 people annually offering tourists the opportunity to witness the big catch, enjoy local seafood, and mingle with locals.

The island also has well maintained beaches. Grand Isle State Park, on the east end of the island, is the only state-owned and operated beach on the Louisiana Gulf Coast. The beach is a popular destination for people living in South Louisiana. In 2010, Yahoo Travel named Grand Isle one of America's Top 10 winter beach retreats. In 2011, Yahoo travel names Grand Isle one of the Top 5 island getaways.

The island is home to the Coast Guard Station Grand Isle 29°15′55″N 89°57′23″W / 29.26528°N 89.95639°W located on the eastern end of the island.

Grand Isle Migratory Bird Festival

The Grand Isle Migratory Bird Festival, held annually in April, was first established in 1997 by several nature organizations dedicated to the preservation and restoration of the Grand Isle's chenier habitat.[11] The idea for the project of preserving and establishing the chenier habitat in order for tourists and bird watchers to see the migratory birds was first established by the Grand Isle Community Development Team. The project was then picked up a year later by the Barataria-Terrebonne Nation Estuary Program to help in the development and preservation of the habitat as well as the advertisement of the Grand Isle Migratory Bird Festival.

Originally, the festival was held on a single day, but due to increased popularity and funding, the festival has grown into a three-day event.[11] Sponsors of the Grand Isle Migratory Bird Festival believe that future efforts will be more successful if more people are educated about not only the identification of the birds that migrate through the island, but also the identification and importance of the plants the birds utilize. Each day during the festival, multiple tours are given throughout the diverse habitats of Grand Isle where experienced guides instruct beginner birders on the different techniques used to find and identify birds as well as the ecological aspects of the island. Other tours are offered that guide visitors through the chenier forests and teach them about the native plants found on the island, including the species that are not only edible to birds but to people as well. Other features of the festival include bird banding and mist netting demonstrations, seminars on what to look for when choosing a pair of binoculars or a spotting scope, as well as games and other activities.

Described as a barrier island, Grand Isle consists of mainly marsh habitat, beaches and chenier forests which attract numerous species of migratory birds.[12] The presence of these hardwood forests allows for the seasonal arrival and departure of major flocks of birds that migrate across the Gulf of Mexico to South America during both the fall and spring migrations.[13] The Migratory Bird Festival is held annually and coincides with the arrival of the spring migrants returning from their winter habitat in the south.

Chenier habitat

Chenier habitats are not limited to Grand Isle, but were historically found in wetlands throughout the southeastern coasts of Louisiana called the Chenier Plain.[12] Today, the Chenier Plain consists of uplands, wetlands, and open water that extends from Vermillion Bay, Louisiana to East Bay, Texas. Of the original 500,000 acres (200,000 ha) that had existed, an estimated 5,000 to 10,000 square acres remain.[14] Chenier forests consist of hardwood trees, primarily oaks and hackberries, as well as a variety of other vegetation such as mulberry, honeylocust, water oak, green ash, and American elm, all which grow along slightly elevated ridges. These ridges are the result of the build-up of sediment from periodic shifts of the Mississippi River's delta and can range in size from 1–3 metres (3.3–9.8 ft) high and between 30–450 metres (98–1,476 ft) wide.[12] Because of the slightly higher elevation, chenier forests not only allow for the growth of hardwood trees that support the variety of migratory birds that pass through Grand Isle, but also act as a barrier for salt water intrusion into a marsh during storm surges.[15] Typically, marshes that are north of a chenier are less saline than marshes that are closer to the gulf.

The cover of a chenier forest provides for migratory birds a place to rest before or after making the flight across the Gulf of Mexico and in some species of birds, the habitat is essential for breeding.[16] However, some studies suggest that it is not just the cover that habitats like chenier forests provide that attract migratory birds, but it is the food availability that is the principal factor in migratory bird stopover. Stopover is a term used for when flocks of migratory birds pause in a certain area to rest and/or feed.[17] Studies have shown that significant stopover occurs more frequently as flocks of migratory birds near the coast.[18] There is a correlation between large densities of birds occurring in continuous hardwood forests, such as old-growth cheniers. Studies done on forest cover indicate that as the amount of cover increased, arthropod abundance and the presence of fleshy, fruit bearing vegetation increased as well, and that migratory birds use forest cover as an indicator of greater habitat quality, thus a better food source per impending journey across the Gulf of Mexico.[16]

The Grand Isle Birding Trail

The birding trails along Grand Isle consists of nearly sixty acres of marsh and chenier habitat and are divided up into six tracts that are managed by the Louisiana Nature Conservancy and the Grand Isle Community Development Team.[19] The trails mainly consist of tracts procured by the Grand Isle Nature Conservancy or donated by local landowners. However, because some of the boundaries of the tracts are partially fragmented, the chenier habitat can sometimes expand into private property. But due to the increased popularity of the Migratory Bird Festival, private landowners will generally allow bird watchers and ornithologists permission onto their land. Some residents will go as far as to post signs that say "Bird Friendly" as a way to invite bird watchers onto their property.[19]

The Grilleta Tract was established by a donation of ten acres by the Xavier Grilleta of B&G Services in 1998.[11] In 2001, an additional three acres were acquired that were adjacent to the original property. Although slightly smaller than the Port Commission Marsh, the Grilleta Tract is mostly chenier habitat and is considered the center of the Grand Isle Birding Trail. This stand of forest is one of only two undisturbed chenier forests that still exist on the island. In addition to live oaks, in which a select few are over 125 years old, the area supports a variety of trees and shrubs such as red mulberry, black willow, red bay.

The Grand Isle Port Commission Tract is roughly 22 acres and is located on the western part of the island at the corner of Ludwig Lane.[11] Two hundred eighty feet of boardwalk allow access to the salt marsh tidal ponds that dominate the area. In this tract, birders can spot a variety of passerines, raptors, colonial birds roosting in the sparse chenier habitat, and wading birds.[20] The second largest stretch of forest is a combination of the Maples tract and the Landry-Leblanc tract. Because of its in the vicinity of a local grocery store, it is locally named the Sureway Woods. Together, the Maples tract and the Landry-LeBlanc tract comprise twenty acres of chenier forest.

The remaining two tracts on the island consist of the Cemetery Woods which is property of Louisiana State University and the Govan Tract.[11] The Cemetery Woods is roughly four and a half acres and like the Grilleta Tract, it contains old growth trees which are over 125 years old. In addition to the hardwood forest, the property contains salt flats and marshland which promote the habitation of ducks, moorhens, grebes, and other wading birds. The Govan Tract was donated by the Govan family to the Nature Conservancy in 2003. Originally, the land had belonged to the Govan family since the late 1800s. The tract only consists of half an acre, but within the tract, the mass availability of lives oaks, hackberries, dewberry, and poison oak attracts birds such as painted buntings, red-winged blackbirds, warblers, and other passerines that can been seen during the migratory season.

In addition to the Grand Isle Birding Trail, bird watchers can also see marine birds such as gulls, terns, pelicans, and other shorebirds from the Grand Isle State Park located at the northeast end of the island.[16]

Restoration

In 1998, the State of Louisiana and its federal and local partners approved a coastal restoration project called Coast 2050: Toward a Sustainable Coast.[21] It is a $14 billion fund that is hoped to be allocated over 50 years in around 77 restoration projects with the aim of creating a sustainable ecosystem of coastal Louisiana.[22] While the plan focuses on all of Louisiana, restoration of the Barataria Basin was the first priority and Grand Isle is at the mouth of Barataria Bay.[21] On February 18, 2000, the United States Army Corps of Engineers and the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources signed an agreement to initiate a restoration plan to this basin. The loss of wetland in Barataria Bay is estimated at about 11 square miles per year from 1978-1990 (Fuller et al. 1995).[21] Most strategies in the Barataria Basin region depend on the overall input, movement, and circulation of water, sediment, and nutrients in the basin.[21] Other strategies can be implemented independently of these considerations.[21] These include barrier shoreline restoration, marsh creation in the southwestern basin, and a delta-building diversion from the lower Mississippi.[21] The completion of Coast 2050 was to restore and protect 450,000 acres of wetland.[23] Congress had not approved the Coast 2050 plan, and when Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Rita hit, Congress was studying a less costly, scaled down proposal which could be initiated in the span of a decade.[23]

In April 2009, the Mississippi River Sediment Delivery System was proposed to channel dredged sediment from the Mississippi River to the wetlands in South Louisiana to restore 474 acres (192 ha) of tidal marsh.[22] Approximately 200 million tons of sediment flows down the Mississippi River annually, of which the Army Corps of Engineers dredges about 60 million cubic yards of the sediment to maintain Louisiana's waterways.[22] According to the project documents, if successful, the Sediment Delivery system could potentially create 18 square miles (47 km2) of marsh a year and reduce wetland losses by as much as two-thirds.[22] The dredged sediment will be piped to Bayou Dupont via a 1-meter (3 ft 3 in) pipe, to an 500-acre (200 ha) area of open water and broken marsh.[22] Once the area has been adequately filled, it will be planted with marsh grasses.[24] It is estimated that the project will cost $28 million and be completed by August 2009.[22]

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration put up $3 million in the summer of 2009 in federal stimulus grants to restore a protective marsh that will shield the island from backwater flooding.[25] The money will help Grand Isle strengthen its natural defenses, provide better hurricane protection, while also preserving a critical barrier island that buffers inland parishes from the full force of hurricanes.[25] In 2009, the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources used $3 million to dredge sediment from the Mississippi River and create 50 acres (20 ha) of tidal marsh.[25] Not only will the marsh help support recreational and commercial fisheries by providing a healthy habitat, officials said, but it will also buffer the island and reduce storm surge and flooding.[25]

Also in 2009, the Nature Conservancy received a $4 million grant for its Grand Isle shoreline-restoration project, which will create four miles of oyster reefs along the beach in Grand Isle and Biloxi Marsh.[25] (see Oyster Reef Restoration) The frames eventually grow into 2-to-3-foot-high (0.61–0.91 m) oyster reefs that buffer the shore and create productive ocean habitats for fish.[25] Once these reefs have fully restored themselves, they will also help filter the water.[26] The Nature Conservancy hope that these oysters colonize on breakwater structures and that the space on these breakwater structures increase biodiversity.[27]

In response the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill, the Coalition and the National Wildlife Foundation organized the planting of more than 1,600 mangroves in Grand Isle State Park on June 25, 2011.[28] They hope that this planting will help stabilize the sediment and sand and provide habitat for wildlife, specifically pelicans.[28]

On September 29, 2012, the Coalition to Restore Coastal Louisiana (CRCL) and the Abita Brewing Company partnered together to bring out more than 100 volunteers to help restore and protect the beach dunes at Grand Isle State Park in response to Hurricane Isaac (2012).[29] It was the first project undertaken in Grand Isle since Hurricane Issac made landfall.[29] Volunteers installed dune fences and planted more than 12,000 plugs of dune grass. This will help stabilize the fragile beach along Grand Isle.[29] Abita Beer and CRCL together implemented this and other restoration projects which will directly restore dune habitat and strengthen Grand Isle State Park and other sites in the future.[29] "Save Our Shore: Volunteer for the Coast" restoration projects such as this one will also allow volunteers the opportunity to learn about coastal land loss while participating in projects that promote Louisiana's ties to our coast and culture.[29]

Media

- Grand Isle was the setting for the novel The Awakening (1899) by Kate Chopin. Chopin spent her summers in Grand Isle for over a decade.

- The second episode of Route 66 was filmed here, in 1960. The plot involved the local shrimp-fishing community imperiled by an approaching hurricane.

See also

References

- 1 2 "Grand Isle, Louisiana". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. June 4, 1980. Retrieved 2007-12-12.

- ↑ "2016 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved Jul 2, 2017.

- 1 2 "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved June 9, 2017.

- ↑ http://www.hurricanecity.com/city/grandisle.htm

- ↑ "NBC5.com - Katrina: At A Glance" (2005-09-15), NBC5.com WMAQ TV Chicago, web: NBC5-Chicago.

- ↑ Beitler, Stu. "Last Island, LA Hurricane, Aug 1856". Louisiana Disasters. gendisasters.com. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ↑ "Climate Statistics for Grand Isle, Louisiana". Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on May 12, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2013-09-11. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ Grand Isle Library. Jefferson Parish Library. Retrieved on September 28, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "The Grand Isle Migratory Bird Festival". Barataria-Terrebonne National Estuary Program. Retrieved November 2, 2011.

- 1 2 3 Neyland, R; Meyer H. "Species Diversity of Louisiana Chenier Woody Vegetation Remnants.". Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society. 124: 254–261. JSTOR 2996613. doi:10.2307/2996613.

- ↑ Lincoln, FC; SR Peterson. "Migration of Birds". U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 16: 119–124. Archived from the original on 2006-04-11.

- ↑ Louisiana Depart of Wildlife and Fisheries (2005). "Conservation Habitats and Species Assessments" (PDF). LACWCS.

- ↑ Russell, RJ; HV Howe (1935). "Cheniers of Southwestern Louisiana". Geographical Review. 25: 449–461. JSTOR 209313. doi:10.2307/209313.

- 1 2 3 Wilson, Scott; Shannon LaDeau; Anders Tottrup; Peter Marra (2011). "Range-wide effects of breeding- and nonbreeding-season climate on the abundance of a Neotropical migrant songbird". Ecology. 92: 1789–1798. doi:10.1890/10-1757.1.

- ↑ Buler, Jeffrey; Frank R. Moore; Stefan Woltmann (2007). "A Multi-Scale Examination of Stopover Habitat Use By Birds". Ecology. 88 (7): 1789–1802. JSTOR 27651296. doi:10.1890/06-1871.1.

- ↑ Deppe, Jill L.; John T. Rotenberry (2008). "Scale-Dependent Habitat Use by Fall Migratory Birds: Vegetation Structure, Floristics, and Geography". Ecological Monographs. 78: 461–487. JSTOR 27646145. doi:10.1890/07-0163.1.

- 1 2 Galliano, Sue. "President of the Grand Isle Development Team".

- ↑ "Grand Isle". Orleans Audubon Society. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Coast2050". Coast2050.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Uplifting the Coast". Uplifiting the Coast.

- 1 2 "Hurricanes Katrina and Rita and the Coastal Louisiana Ecosystem Restoration" (PDF). Report from Congress.

- ↑ "Bayou Dupont Sediment Delivery System (BA-39)". CWPPRA.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Federal money to help Grand Isle coastal restoration projects". NOAA and the NC.

- ↑ "Oyster Restoration". The Nature Conservancy Camp.

- ↑ "Grand Isle Oyster Reef Project" (PDF). The Nature Conservancy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-07.

- 1 2 "Restoration efforts underway in oil spill-impacted Grand Isle State Park". Restoration efforts underway in oil spill-impacted Grand Isle State Park. Archived from the original on 2014-08-15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "CRCL and Abita Beer Partner on Grand Isle Restoration Project". CRCL and Abita Beer Partner.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Grand Isle, Louisiana. |

- Town of Grand Isle

- Island community all but vanishes in hurricane's wake, an August 31, 2005, article about the damage from Hurricane Katrina

- Grand Isle, Louisiana: Voices From a Community Devastated by BP Oil Spill - video report by Democracy Now!

- GrandIsle.us History of Grand Isle, old and modern photographs, things to do in Grand Isle