Birmingham New Street station

| Birmingham New Street | |

|---|---|

|

The east end of the station. Note the newly rebuilt and refurbished building which opened in 2015. | |

| Location | |

| Place | Birmingham |

| Local authority | City of Birmingham |

| Coordinates | 52°28′40″N 1°53′56″W / 52.47777°N 1.89885°WCoordinates: 52°28′40″N 1°53′56″W / 52.47777°N 1.89885°W |

| Grid reference | SP069866 |

| Operations | |

| Station code | BHM |

| Managed by | Network Rail |

| Number of platforms | 13 (1-12a, 1-12b + 4c, which is a separate platform at the end of 4b) |

| DfT category | A |

|

Live arrivals/departures, station information and onward connections from National Rail Enquiries | |

| Annual rail passenger usage* | |

| 2011/12 |

|

| – Interchange |

|

| 2012/13 |

|

| – Interchange |

|

| 2013/14 |

|

| – Interchange |

|

| 2014/15 |

|

| – Interchange |

|

| 2015/16 |

|

| – Interchange |

|

| Passenger Transport Executive | |

| PTE | Transport for West Midlands |

| Zone | 1 |

| History | |

| Original company | London & North Western Railway |

| 1 June 1854 | First opened |

| 8 February 1885 | Extension opened |

| 1964-1967 | Rebuilt |

| 2010-2015 | Redeveloped |

| National Rail – UK railway stations | |

| * Annual estimated passenger usage based on sales of tickets in stated financial year(s) which end or originate at Birmingham New Street from Office of Rail and Road statistics. Methodology may vary year on year. | |

|

| |

Birmingham New Street is the largest and busiest of the three main railway stations in the city centre of Birmingham, England. It is a central hub of the British railway system. It is a major destination for Virgin Trains services from London Euston, Glasgow Central and Edinburgh Waverley via the West Coast Main Line,[1] and the national hub of the CrossCountry network – the most extensive in Britain, with long-distance trains serving destinations from Aberdeen to Penzance.[2] It is also a major hub for local and suburban services within the West Midlands, including those on the Cross City Line between Lichfield Trent Valley and Redditch and the Chase Line to Walsall and Rugeley Trent Valley.

The station is named after New Street, which runs parallel to the station, although the station has never had a direct entrance to New Street except via the Shopping Centre. Historically the main entrance to the station was on Stephenson Street, just off New Street. Today the station has entrances on Stephenson Street, Smallbrook Queensway, Hill Street and Navigation Street.

New Street is the seventh busiest railway station in the UK and the busiest outside London, with 39 million passenger entries and exits between April 2015 and March 2016.[3] It is also the busiest interchange station outside London, with over 5.8 million passengers changing trains at the station annually.[4]

The original New Street station opened in 1854. At the time of its construction, the station had the largest single-span arched roof in the world,[5] In the 1960s, the station was completely rebuilt. An enclosed station, with buildings over most of its span and passenger numbers more than twice those it was designed for, the replacement was not popular with its users. A £550m redevelopment of the station named Gateway Plus opened in September 2015. It includes a new concourse, a new exterior facade, and a new entrance on Stephenson Street.[6][7]

Around 80% of train services to Birmingham go through New Street.[8] The other major city-centre stations in Birmingham are Birmingham Moor Street and Birmingham Snow Hill. On the outskirts, closer to Solihull, is Birmingham International, which serves Birmingham Airport and the National Exhibition Centre.

Since 30 May 2016, New Street has been served by the Midland Metro tram line, when it became the new terminus of Line 1, following the opening of the city-centre extension from Birmingham Snow Hill. The Grand Central New Street Station tram stop is located outside the station's main entrance on Stephenson Street.[9]

History

The first railway stations

New Street station was built by the London and North Western Railway (LNWR) between 1846 and 1854. It was built in the centre of Birmingham, replacing several earlier rail termini on the outskirts of the centre, most notably Curzon Street, which had opened in 1838, and was no longer adequate for the level of traffic.[10]

Until 1885 the LNWR shared the station with the Midland Railway, whose trains also used the station. However, in 1885 the Midland Railway opened its own extension alongside the original station for the exclusive use of its trains, effectively creating two stations side-by-side. The two companies stations were separated by a central roadway; Queens Drive.[10]

Traffic grew steadily, and by 1900 New Street had an average of 40 trains an hour departing and arriving, rising to 53 trains in the peak hours.[11]

Original LNWR station

The London and North Western Railway had obtained an Act of Parliament in 1846, to extend their line into the centre of Birmingham, which involved the acquisition of some 1.2 hectares (3 acres) of land, and the demolition of 70 or so houses in Peck Lane, The Froggery, Queen Street, and Colmore Street.[12] The Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion chapel, on the corner of Peck Lane and Dudley Street, which had only been built six years before,[13] was also demolished.[14] The station was formally opened on 1 June 1854,[8] although the uncompleted station had already been in use for two years as a terminus for trains from the Stour Valley Line, which entered the station from the Wolverhampton direction. On the formal opening day, the LNWR's Curzon Street railway station was closed to regular passenger services, and trains from the London direction started using New Street.[10]

The station was constructed by Messrs. Fox, Henderson & Co. and designed by Edward Alfred Cowper of that firm, who had previously worked on the design of The Crystal Palace. When completed, it had the largest arched single-span iron and glass roof in the world, spanning a width of 211 feet (64 m) and being 840 ft (256 m) long.[10][8] It held this title for 14 years until St Pancras station opened in 1868. It was originally intended to have three spans, supported by columns, however it was soon realised that the supporting columns would severely restrict the workings of the railway. Cowper's single-span design, was therefore adopted, even though it was some 62 feet (19 metres) wider than the widest roof span at that time.[15][16] George Gilbert Scott praised Cowper's roof at New Street, stating “An iron roof in its most normal condition is too spider-like a structure to be handsome, but with a very little attention this defect is obviated. The most wonderful specimen, probably, is that at the great Birmingham Station . . . ”[17] When first opened, New Street was described as the "Grand Central Station at Birmingham".[18]

The internal layout of tracks and platforms was designed by Robert Stephenson and his assistants; the station contained a total of nine platforms, comprising four through, and five bay platforms.[10]

The main entrance building on Stephenson Street incorporated Queen's Hotel, designed by John William Livock, which was opened on the same day. The Queen's Hotel was built in an Italianate style and was originally provided with 60 rooms. The hotel was expanded several times over the years, and reached its final form in 1917 with the addition of a new west wing.[8][19]

The scale of the station at this time can be taken from the station's entry in the 1863 edition of Bradshaw's Guide:[20]

| “ | The interior of this station deserves attention from its magnitude. The semicircular roof is 1,110 feet long, 205 feet wide and 80 feet high, composed of iron and glass, without the slightest support except that afforded by the pillars on either side. If the reader notice the turmoil and bustle created by the excitement of the arrival and departure of trains, the trampling of crowds of passengers, the transport of luggage, the ringing of bells, and the noise of two or three hundred porters and workmen, he will retain a recollection of the extraordinary scene witnessed daily at Birmingham Central Railway Station. | ” |

The roof of the original station was strengthened with additional steel tie bars during 1906–7, this was done as a precaution following the collapse of a similar roof at Charing Cross station in 1905.[21]

The interior of the original LNWR station in the late 19th Century, with its once record breaking roof

The interior of the original LNWR station in the late 19th Century, with its once record breaking roof Victorian image of the interior of the LNWR station.

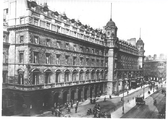

Victorian image of the interior of the LNWR station. The main entrance building to the old station on Stephenson Street, incorporating Queen's Hotel, c1920

The main entrance building to the old station on Stephenson Street, incorporating Queen's Hotel, c1920 The main entrance to the old station on Stephenson Street, including Queens Hotel in 1962.

The main entrance to the old station on Stephenson Street, including Queens Hotel in 1962.

Midland Railway extension

Midland Railway trains that had used Curzon Street began to use New Street from 1854. However, its use by the Midland Railway was limited by the fact that those trains going between Derby and Bristol would have to reverse, so many trains bypassed New Street and ran through Camp Hill. This was remedied in 1885, when a new link to the south; the Birmingham West Suburban Railway was extended into New Street, this allowed through trains to and from the south-west to run through New Street without reversing.[22]

To cope with the increase in traffic this would bring, the station required an extension, the construction of which began in 1881. A number of buildings, mostly along Dudley Street were demolished to make room for it, including a number of cottages, some business premises and a small church.[10] Built immediately to the south of the original station, the extension contained four through platforms and one bay.[23] It consisted of a trainshed with a glass and steel roof comprising two trussed arches, 58 ft (18 m) wide by 620 ft (189 m) long, and 67 ft 6 in (21 m) wide by 600 ft (183 m) long. It was designed by Francis Stevenson, Chief Engineer to the LNWR.[8] The extension was opened on 8 February 1885.[8] With its completion, New Street nearly doubled in size, and became one of the largest stations in Britain, covering an area of over twelve acres (4.9 ha).[19]

In early 1885 the number of daily users of the station was surveyed. On a Thursday, the number was 22,452 and on a Saturday it was 25,334.[24]

Initially the extension was used by both the LNWR and Midland Railway, but from 1889, it became used exclusively by Midland Railway trains,[25] It was separated from the original LNWR trainshed by Queens Drive, which became a central carriageway, but the two were linked by a footbridge which ran over Queens Drive, and across the entire width of both the LNWR and Midland stations.[26] Queens Drive was lost in the rebuilding of the 1960s, but the name was later carried by a new driveway which served the car park and a tower block, and is the access route for the station's taxis.

LMS and British Rail

In 1923, the LNWR and Midland Railway, with others, were grouped into the London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS) by the Railways Act 1921. In 1948, the railways were nationalised and came under the control of British Railways.

During World War II, Cowper's roof sustained extensive bomb damage as a result of air raids during the Birmingham Blitz. After the war, the remains of the roof were dismantled after being deemed beyond economic repair. It was replaced with basic 'austerity' canopies over the platforms, made from surplus war materials, which remained in use until the station was rebuilt in the 1960s.[27][28][10]

1960s rebuild

The station was completely rebuilt in the 1960s as part of the West Coast Main Line modernisation programme. Demolition of the old station and Queen's Hotel began in 1964 and was not completed until 1966.[29] The rebuilt New Street station was opened on 6 March 1967 to coincide with the introduction of electric expresses on the West Coast Main Line. It cost £4.5 million to build[30] (equivalent to £73,660,000 in 2015).[31]

.jpg)

The new station was designed by Kenneth J. Davies, lead planner for British Rail London Midland Region.[32] Twelve through platforms replaced the eight through and six bay platforms of the previous station.[30] The platforms were covered over by a seven-acre (2.8 ha) concrete deck, supported by 200 columns, upon which the concourse and other buildings were constructed. Escalators, stairs and lifts are provided to reach the platforms from the concourse. The new station had sold its air rights, leading to the construction of the Pallasades Shopping Centre (then known as the Birmingham Shopping Centre) above the station between 1968 and 1970.[19][32][33] The public right of way across the station, which had previously been maintained by the station footbridge, was retained in the new station via a winding route through the shopping centre.[34] The station and the Pallasades are now partly integrated with the Bullring Shopping Centre via elevated walkways above Smallbrook Queensway.

Also above the station was a nine-storey office block called Ladywood House,[35] and a multi-storey car park dating from the 1970s. The car park closed in May 2012 and was demolished to provide space for the new concourse and rebuilt.[36] Stephenson Tower, a 20-storey residential tower block, was built alongside the station between 1965 and 1966.[37] The tower, designed by the City Architect of Birmingham, was demolished in March 2012 as part of the station redevelopment.[38]

In 1987, twelve different horse sculptures by Kevin Atherton, titled Iron Horse, were erected between New Street station and Wolverhampton at a cost of £12,000.[39][40] One stands on a platform at New Street.[41]

Due to its enclosed sub-surface platforms, New Street was designated as an underground station by the fire service. In the 1990's a number of changes had to be made to the station in order to comply with stricter fire regulations, introduced for underground stations as a result of the 1987 King's Cross fire. In 1993, a new enclosed footbridge was opened at the Wolverhampton end of the station, with access to the platforms separate from the main building: this was built primarily as a fire exit, but the new exit from the station into Navigation Street was opened to the public. All wooden fittings were removed from the platforms, and new fire doors were also installed at the foot of the stairs and elevators on the platforms.[34]

The concrete constructed design of the 1960s station was widely criticised for being ugly.[42] An enclosed station, with buildings over most of its span and passenger numbers more than twice those it was designed for,[5] by 2007 it was not popular with its users, having a customer satisfaction rate of only 52%, the joint lowest of any Network Rail major station.[43] The 1960s station was redeveloped in 2010-15.

- The concrete external architecture of the 1960s station

.jpg) The western end of the station.

The western end of the station.- A Virgin Trains Pendolino waiting at Platform 2 at New Street in 2009.

The former station concourse at rush hour.

The former station concourse at rush hour. "Iron Horse" sculpture.

"Iron Horse" sculpture.

New Street signal box

The power signal box at New Street was completed in 1964.[8] The signal box is a brutalist building with corrugated concrete architecture, designed by Bicknell & Hamilton in collaboration with William Robert Headley, the regional architect for British Railways London Midland Region.[44] The four-storey structure is at the side of the tracks connected to Navigation Street. It is now a Grade II-listed building.[45][46]

Don's Miniature New Street

A Sutton Coldfield model railway enthusiast, Don Jones, built a scale model of the entire 1960s station, and surrounding buildings including the Rotunda, the old Head Post Office and the signal box, at OO scale, and held open days to raise funds for local charities.[47][48] Private visits were held for Robert Redford and King Hussein of Jordan.[48]

2010–2015 redevelopment

In November 2003 the station was voted the second biggest "eyesore" in the UK by readers of Country Life magazine.[49] This might be blamed on the sub-surface nature of the station and the 1960s architecture. New Street was voted joint worst station for customer satisfaction with Liverpool Lime Street and East Croydon, with only 52% satisfied; the national average was 60%.[43]

The 1960s station also had become inadequate for the level of traffic it was dealing with; it had been designed with capacity for 650 trains and 60,000 passengers per day. In 2008 there were 1,350 trains and over 120,000 passengers per day.[50] By 2013 it was 140,000 passengers per day.[51] This made overcrowding and closures on safety grounds more common.[52]

A feasibility study into the redevelopment of the station was approved in January 2005. Designs were shown to the public in February 2006 for a new Birmingham New Street Station in a project known as Gateway Plus.[53]

A regeneration scheme was launched in 2006[54] and evolved through names such as Birmingham Gateway, Gateway Plus, and New Street Gateway. The scheme proposed complete rebuilding of the street-level buildings and refurbishment of the platforms by 2013, with track and platform level remaining essentially unchanged.

The approved planning application of August 2006 showed a glass façade with rounded edges. The entrance on Station Street originally included two curved 130-metre-tall towers on the site of Stephenson Tower. Due to the economic slowdown, the "twin towers" plan was shelved.[55]

In February 2008, the Secretary of State for Transport, Ruth Kelly, announced that the Department for Transport would provide £160 million in addition to £128 million that through the government White Paper Delivering a Sustainable Railway.[56] A further £100 million came from the Department for Business Enterprise and Regulatory Reform and channelled through Advantage West Midlands, the regional development agency. The announcement brought total government spending on the project to £388 million.[57] After earlier proposals were discarded, six architects were shortlisted to design the new station following a call for submissions,[58] and it was announced in September 2008 that the design by Foreign Office Architects had been chosen.[59]

.jpg)

The approved plans for the redevelopment included:[7]

- A new concourse three and a half times larger than the 1960s concourse, with a domed atrium at the centre to let in natural light.

- Refurbished platforms reached by new escalators and lifts.

- A new station facade, and new entrances.

The fact that the Gateway development leaves the railway capacity of the station more or less unaltered has not escaped attention. In July 2008 the House of Commons Transport Committee criticised the plans: it was not convinced they were adequate for the number of trains which could end up using the station. It said if the station could not be adapted, the government needed to look for alternative solutions.[60]

Work began on the redevelopment on 26 April 2010.[61] Construction was completed in phases to minimise disruption. On 28 April 2013, one half of the new concourse was opened to the public, and the old 1960s concourse was closed for redevelopment, along with the old entrances.[62] The complete concourse opened on 20 September 2015, the Grand Central shopping centre opened on the 24th.[63][64] The refurbished Pallasades Shopping Centre was renamed 'Grand Central Birmingham' and includes a new John Lewis store.[65]

During heavy winds on 30 December 2015, several roof tiles blew off, landing in the adjacent Station Street, which was therefore closed by the police as a precautionary measure.[66]

Services

Operations

Railway operations

New Street is the hub of the West Midlands rail network, as well as being a major national hub. The station is one of seventeen operated and managed by Network Rail,[67] Network Rail also provides operational staff for the station .

Station staff are provided on all platforms to assist with the safe 'dispatch' of trains. For operational reasons all trains departing New Street much be dispatched via the use of Right Away (RA) indicators. RA indicators display a signal informing the train driver it is safe to start the train, instead of using more traditional bell or hand signals.

The 12 through platforms are divided into a and b ends, with an extra bay platform called 4c between 4b and 5b, with the b end of the station towards Wolverhampton, this in effect allows twice the platforms. Longer trains that are too long for one section of the platform occupy the entire length of the platform, such as Class 390 or HSTs.

Trains departing towards Proof House Junction (a end) can depart from any platform, but there are restrictions on trains departing from the b end. All platforms can accommodate trains heading towards Wolverhampton, however due the platform layout and road bridge supports, only 5–12 can accommodate trains heading towards Five Ways. There are a number of sidings on the station for the stabling of trains; between platforms 5/6, 7/8, 9/10. The bay platforms at either end of platform 12 have been removed during the current rebuild. The sidings in front of New Street signal box have also been removed.

All signalling is controlled by New Street power signal box at the Wolverhampton or b end of the station; it can be seen at street level on Navigation Street. The station is allocated the IATA location identifier QQN.

Approach tunnels

All trains arriving and departing must use one of the several tunnels around the station.[10]

- New Street North Tunnel – also known as Monument Lane Tunnel, heads westwards towards Soho Junction & Wolverhampton, and passes under the National Indoor Arena. This tunnel is 760 yards (695 metres) long. It was opened in 1852 as part of the Stour Valley Line, and holds two tracks.

- New Street South Tunnel – 266 yards (243 metres) long, heading eastbound, passing under the Bullring, and Birmingham Moor Street station, heading towards Duddeston, Adderley Park, the Camp Hill Line and the Derby lines towards Tamworth. This tunnel opened in 1854, originally holding two tracks, it was widened in 1896 to hold four tracks,

- Gloucester Line Tunnels – are four separate tunnels heading south-west towards Five Ways. Heading from New Street in sequence the tunnels are named Holiday Street Tunnel, 93 yards (85 metres) long; Canal Tunnel, 224 yards (204 metres) long, passing under the Birmingham Canal Navigations; Granville Street Tunnel, 81 yards (74 metres) long; and Bath Row Tunnel, 209 yards (191 metres) long. These tunnels opened in 1885 as part of the Birmingham West Suburban Railway and hold two tracks.

Customer service and ticketing

Network Rail, as well as operating the station, operated a customer reception located on the main concourse. Booking office and barriers are split between Virgin Trains and London Midland, with customer service or floor walker staff provided by CrossCountry. Virgin Trains operates a first class lounge and Network West Midlands also provides a public transport information point of the station.

New Street is a penalty fare zone, which is operated by London Midland on its trains and at the automatic ticket barriers at the station.

Train operating companies

Since privatisation of British Rail there have been no fewer than 10 train companies operating into New Street: Arriva Trains Wales, Central Trains, CrossCountry, London Midland, Silverlink, Virgin Trains, Virgin CrossCountry, Wales & Borders, Wales & West, Wrexham & Shropshire.

Currently Arriva Trains Wales, London Midland, Virgin Trains and CrossCountry provide services from New Street. Chiltern Railways have on occasion used New Street during engineering works.

London Midland operates a traincrew depot at the station and stables some trains overnight around the station. For the most part they use Soho TMD in Smethwick for electric traction units, with its non-electric units kept at Tyseley TMD to the southeast of Birmingham.

CrossCountry also operates a traincrew depot at the station; it uses Tyseley TMD for the Class 170 units, and its Voyagers are based at Barton under Needwood depot near Burton on Trent, Staffordshire.

Train services

The basic Monday to Saturday off-peak service in trains per hour (tph) is as follows:

- 3tph to London Euston via Coventry

- 1tph to Glasgow Central or Edinburgh Waverley (alternating each hour) via Preston and Carlisle.

- 2tph to Manchester Piccadilly via Stafford and Stoke-on-Trent.

- 2tph to Bristol Temple Meads with one carrying on to Plymouth and some as far as Penzance.

- 2tph to Nottingham via Derby.

- 2tph to Leicester with one carrying on to Stansted Airport via Peterborough.

- 2tph to Reading via Oxford, some of which continue to Southampton Central and Bournemouth.

- 1tph to Cardiff Central via Gloucester & Newport.

- 1tph to Newcastle Central via Sheffield and Doncaster.

- 1tph to Edinburgh Waverley via Leeds and Newcastle Central, continuing alternately to Glasgow Central or Dundee and Aberdeen.

- 3tph to Longbridge

- 3tph to Redditch

- 2tph to Four Oaks

- 2tph to Lichfield City

- 2tph to Lichfield Trent Valley

- 2tph to Wolverhampton

- 3tph to Walsall

- 1tph to Rugeley Trent Valley

- 3tph to London Euston via Coventry & Northampton

- 2tph to Liverpool Lime Street via Crewe

- 1tph to Birmingham International

- 1tph to Hereford via Bromsgrove & Worcester Foregate Street

- 1tph to Shrewsbury

- 1tph to Birmingham International

- 1tph to Shrewsbury, continuing alternately to Chester & Holyhead or Aberystwyth/Pwllheli

| Preceding station | |

Following station | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birmingham International |

Arriva Trains Wales Birmingham - Chester |

Smethwick Galton Bridge | ||

| Arriva Trains Wales Cambrian Line |

||||

| Terminus | CrossCountry Birmingham - Leicester |

Water Orton or Coleshill Parkway | ||

| CrossCountry Birmingham - Stansted Airport |

Coleshill Parkway | |||

| Birmingham International |

CrossCountry Bournemouth - Manchester |

Wolverhampton | ||

| Cheltenham Spa | CrossCountry Bristol-Manchester |

|||

| Leamington Spa | CrossCountry Reading-Newcastle |

Derby | ||

| University | CrossCountry Cardiff-Nottingham |

Wilnecote or Tamworth | ||

| Terminus | ||||

| Cheltenham Spa | CrossCountry Plymouth - Edinburgh |

Tamworth | ||

| Duddeston or Terminus |

London Midland Cross City Line |

Five Ways | ||

| Duddeston | London Midland Cross City Line |

Terminus | ||

| Adderley Park or Stechford or Marston Green |

London Midland West Coast Main Line |

Terminus | ||

| University | London Midland Worcester Shrub Hill/Hereford/Great Malvern — Birmingham |

Terminus | ||

| Terminus | London Midland Birmingham to Gloucester Limited service |

University | ||

| Terminus | London Midland Birmingham-Shrewsbury |

Sandwell and Dudley or Wolverhampton | ||

| Terminus | London Midland (Birmingham-Liverpool) |

Smethwick Galton Bridge | ||

| Terminus | London Midland (Birmingham-Liverpool) |

Coseley | ||

| Duddeston or Terminus |

London Midland Walsall/Birmingham-Wolverhampton (Stopping Services) |

Smethwick Rolfe Street | ||

| Duddeston or Tame Bridge Parkway |

London Midland Birmingham-Walsall/Hednesford/Rugeley |

Terminus | ||

| Birmingham International or Terminus |

Virgin Trains West Coast Main Line |

Sandwell and Dudley or Wolverhampton | ||

| Birmingham International or Milton Keynes Central |

Virgin Trains Birmingham-London |

Terminus | ||

| Virgin Trains Wolverhampton-London |

Sandwell and Dudley | |||

| Birmingham International | Virgin Trains Shrewsbury-London |

Sandwell and Dudley | ||

| Historical railways | ||||

| Monument Lane | London and North Western Railway Stour Valley Line |

Duddeston or Adderley Park | ||

| Terminus | London and North Western Railway Birmingham–Peterborough line |

Adderley Park | ||

| Five Ways | Midland Railway Cross City Line |

Saltley | ||

| Camp Hill | Midland Railway Camp Hill Line |

Terminus | ||

Links to Moor Street and Snow Hill stations

New Street station is 600 metres away from Birmingham Moor Street; the city's second busiest railway station.[68] There is a signposted route for passengers travelling between New Street and Moor Street stations which involves a short walk through a tunnel under the Bullring shopping centre. Although the railway lines into New Street pass directly underneath Moor Street station, there is no rail connection. In 2013 a new direct walkway was opened between the two stations.[69] Birmingham Snow Hill station is 1000 metres away;[68] either a ten-minute walk away to the north, or can be reached via a short tram ride on the Midland Metro.[70]

Accidents and incidents

- On 26 November 1921, a serious accident occurred on the Midland half of New Street station, when an express from Bristol crashed into the rear of a stationary train to Derby, which was standing at platform four and had been delayed due to engine trouble. The collision caused the guards van of the Derby train to telescope with the rear coach. Three people were killed, and twenty four injured. The later inquest ruled that the express had overrun the danger signal due to driver error, and the misty conditions had made the rails moist, leading to wheelslip when the train tried to brake.[71]

Metro tram stop

| Midland Metro tram stop | |

Two Urbos 3 trams at Grand Central tram stop, the one on the left arriving, and the one on the right about to depart for Wolverhampton. | |

| Location |

Stephenson Street Birmingham city centre Birmingham England |

| Line(s) | Line 1 (Birmingham – Wolverhampton) |

| Platforms | 2 |

| History | |

| Opened | 30 May 2016[72] |

| Traffic | |

| Passengers | N/A |

On 30 May 2016, the new Midland Metro tram stop serving New Street was opened outside the station's main entrance on Stephenson Street. The stop is the current terminus of the Midland Metro Line One, and provides a link to Snow Hill station and onwards to Wolverhampton.[9]

Initially, New Street station was planned to act as the terminus of the Midland Metro extension to Line One through the city centre. However, in October 2013 Birmingham City Council voted to extend the new development works, adding a further two stops beyond New Street, at the Town Hall and Centenary Square. As the two additional stops are due to be completed in 2017, New Street will only serve as the terminus of Line One between 2016 and 2017.[73][74] In November 2013 Birmingham City Council indicated a new plan to connect Birmingham New Street with the new High Speed 2 terminus at Curzon Street, Birmingham International Airport and Coventry.

Midland Metro services

Mondays to Saturdays, Midland Metro services to Wolverhampton St George's run at six to eight-minute intervals during the day, and at fifteen-minute intervals during the evenings and on Sundays.[75]

| Preceding station | Following station | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corporation Street | Line 1 | Terminus | ||

| From 2017 | ||||

| Corporation Street | Line 1 | Victoria Square | ||

See also

- Gateway Plus

- Birmingham Snow Hill station

- Birmingham Moor Street railway station

- Transport in Birmingham

- Transport for West Midlands

- Commuter rail in the United Kingdom

- Grand Central, Birmingham

References

- ↑ "Our routes & stations". Virgin Trains. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- ↑ "Routes". CrossCountry. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- ↑ "Estimates of Station Usage 2011/12" (PDF). Office of Rail Regulation. p. 18. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- ↑ "Estimates of Station Usage 2011/12" (PDF). Office of Rail Regulation. p. 19. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- 1 2 "Birmingham New Street's 150-year history revealed as station switchover nears" (Press release). Network Rail. 22 April 2013. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- ↑ "Birmingham New Street update January 2013" (PDF). Jewellery Quarter Development Trust. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- 1 2 "New Street: New Start - The Birmingham Gateway Project". Birmingham City Council. Retrieved 22 June 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Birmingham New Street — History". Network Rail. Retrieved 6 July 2008.

- 1 2 Brown, Graeme (30 May 2016). "WATCH: Midland Metro trams head to Birmingham New Street for first time". Birmingham Mail. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Smith, Donald.J. (1984). New Street Remembered, The Story of Birmingham's New Street Station 1854-1967. Barbryn Press Limited. ISBN 0 906160 05 7.

- ↑ "www.warwickshirerailways.com - lnwrbns_str1295c". www.warwickshirerailways.com. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ↑ Aris's Birmingham Gazette, 16 February 1850.

- ↑ It had been opened Tuesday 16 May 1843. Aris's Birmingham Gazette, 20 November 1848.

- ↑ Aris's Birmingham Gazette, 20 November 1848.

- ↑ "warwickshirerailways.com - lnwrbns_str1295.htm". warwickshirerailways.com. Retrieved 10 Feb 2013.

- ↑ "Edward Alfred Cowper". Graces Guide.co.uk. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ↑ "A Selection of Great Victorian Railway Stations". victorianweb.org. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ "Birmingham New Street Station: An engraved illustration of the entrance to New Street station and the frontage of the Queen's Hotel shortly after the station was opened". www.warwickshirerailways.com.

- 1 2 3 "Birmingham New Street". Network Rail. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ↑ Bradshaw (1863). Bradshaw's Descriptive Railway Hand-book of Great Britain and Ireland. Oxford: Old House. pp. Section III, Page 20. ISBN 9781908402028.

- ↑ "Birmingham New Street Station: View taken from the Queens Hotel from above the South Staffordshire bay showing the entrance to the LNWR's parcel offices on Platform 3 to the left of the footbridge". www.warwickshirerailways.com.

- ↑ "Birmingham New Street Station: An early view of Platform 4 looking East with the entrance off Queens Drive to the left and with a MR train for Kings Norton standing in the platform". www.warwickshirerailways.com.

- ↑ "Birmingham New Street Station: A June 1883 view of the site of the extension to New Street station with Hill Street seen on the left". www.warwickshirerailways.com.

- ↑ "The largest passenger station in the world". Lichfield Mercury. England. 6 February 1885. Retrieved 29 December 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Birmingham New Street Station: View from the Midland Railway's Parcels Offices looking West towards New Street No 2 Signal Box with Platform 6 on the left". www.warwickshirerailways.com.

- ↑ "Birmingham New Street Station: A 1950 view of the layout of the enlarged station with the Midland portion at the bottom and the turntable at the West end of the station". www.warwickshirerailways.com.

- ↑ "Birmingham New Street Station: Looking towards Wolverhampton showing the erection of the temporary roof above the West end of Platforms 2A and 3". www.warwickshirerailways.com.

- ↑ http://www.newstreetnewstart.co.uk/about-the-development/history.aspx

- ↑ Foster, Andy (2007) [2005]. Birmingham. Pevsner Architectural Guides. Yale University Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-300-10731-9.

- 1 2 Christiansen, Rex (1983). A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain, Volume 7 The West Midlands. David St John Thomas David and Charles. ISBN 0946537 00 3.

- ↑ UK Consumer Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Gregory Clark (2016), "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)", MeasuringWorth.com.

- 1 2 Foster, Andy (2007) [2005]. Birmingham. Pevsner Architectural Guides. Yale University Press. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-300-10731-9.

- ↑ "Aerial View of New Street Station 1963". Birmingham City Council. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 6 July 2008.

- 1 2 Boynton, John. Rails Across The City, The Story of the Birmingham Cross City Line. Mid England Books. p. 6. ISBN 0-9522248-0-1.

- ↑ "Prime city centre long leasehold for sale". Ladywood House. 2012.

- ↑ "Pallasades car park to close for demolition and rebuilding" (Press release). New Street: New Start. 25 April 2012. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ "Report No. 7 – New Street Station, Stephenson Street/Navigation Street/Station Street and Smallbrook Queensway, City (C/05066/06/OUT) minutes" (PDF). Birmingham City Council. Retrieved 6 July 2008.

- ↑ Gibbons, Brett (30 March 2012). "Stephenson Tower finally disappears from Birmingham city centre skyline". Birmingham Post.

- ↑ "Iron Horse". Public Monuments and Sculpture Association. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "Kevin Atherton". LUX. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Noszlopy, George T.; Beach, Jeremy (1998). Public Sculpture of Birmingham including Sutton Coldfield. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0-85323-692-5.

- ↑ Jeffrey, Ben (24 July 2007). "New look for 'ugly' New Street". BBC News. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- 1 2 "Revamped station tops train poll". BBC News. 2 August 2007. Retrieved 20 August 2007.

- ↑ Foster, Andy (2007) [2005]. Birmingham. Pevsner Architectural Guides. Yale University Press. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-300-10731-9.

- ↑ Historic England. "Grade II signal box (442131)". Images of England. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- ↑ "Listed buildings". Guardian Unlimited. Retrieved 6 July 2008.

- ↑ "Don's Miniature New Street '88 & '05". Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- 1 2 "Fundraiser Don lines up big day". Birmingham Mail. 24 August 2005. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- ↑ "Windfarms top list of UK eyesores". BBC News. 13 November 2003. Retrieved 29 November 2006.

- ↑ Walker, Jonathan. "New Street Station rebuild gets go-ahead". Birmingham Post. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ "Video feature: new look for Birmingham New Street 27 March 2013". Railway Technology.Com. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- ↑ "New Street Station Compulsory Purchase Order". Birmingham City Council. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ Re-New Street: Change at New Street Archived 18 December 2005 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Rail Air Rights Towers Planned For Birmingham". Skyscrapernews.com. 2006. Retrieved 26 July 2006.

- ↑ Elkes, Neil (24 August 2009). "Twin towers plan for New Street station shelved". Birmingham Mail.

- ↑ "Delivering a sustainable railway - White Paper CM7176". Department for Transport. 24 July 2007.

- ↑ Walker, Jonathan (12 February 2008). "New Street Station rebuild gets go-ahead". Birmingham Post. Archived from the original on 11 March 2008. Retrieved 12 February 2008.

- ↑ Schaps, Karolin (18 February 2008). "Six architects vie for Birmingham New Street station". Building. London. Retrieved 6 July 2008.

- ↑ "Transforming New Street Station". Network Rail / Birmingham City Council / Advantage West Midlands / Centro. Retrieved 3 October 2008.

- ↑ "MPs criticise New Street revamp". BBC News. 21 July 2008. Retrieved 7 August 2008.

- ↑ "Birmingham New Street work to start this year". RailNews. 5 February 2010.

- ↑ "Birmingham New Street station: Concourse opened". BBC News. 28 April 2013. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- ↑ "Birmingham New Street station officially reopens". BBC News. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- ↑ "Grand Central opening: Pictures from Birmingham's newest retail centre". BBC News. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- ↑ "Grand Central". New Street: New Start. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- ↑ "Birmingham Grand Central roof tiles blow off in storm - BBC News". BBC Online. 30 December 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ↑ "Commercial information" (PDF). Complete National Rail Timetable. London: Network Rail. May 2013. p. 43. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- 1 2 "Birmingham New Street Station Map". National Rail. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- ↑ "The first half of the new concourse at Birmingham New Street station will open on 28 April 2013". Network Rail. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ↑ "Walkit.com - Birmingham New Street to Birmingham Snow Hill". Walkit.com. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ↑ "1921 accident report" (PDF). Railways Archive. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- ↑ "Midland Metro Grand Central extension will open Monday 30th May". British Trams Online.

- ↑ Walker, Jonathan (16 February 2012). "£128m Birmingham Midland Metro extension from Snow Hill Station to New Street Station set to create 1,300 jobs gets go-ahead". Birmingham Mail. Archived from the original on 3 August 2012. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ "Birmingham City Centre Extension and Fleet Replacement". Centro. Archived from the original on 1 March 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ "Network West Midlands timetable". Network West Midlands. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

Further reading

- Foster, Richard, Birmingham New Street. The Story of a Great Station Including Curzon Street. 1 Background and Beginnings. The Years up to 1860. Wild Swan Publications, 1990. ISBN 0-906867-78-9

- Foster, Richard, Birmingham New Street. The Story of a Great Station Including Curzon Street. 2 Expansion and Improvement. 1860 to 1923. Wild Swan Publications, 1990. ISBN 0-906867-79-7

- Foster, Richard, Birmingham New Street. The Story of a Great Station Including Curzon Street. 3 LMS Days. 1923-1947. Wild Swan Publications, 1997. ISBN 1-874103-37-2

- Foster, Richard, Birmingham New Street. The Story of a Great Station Including Curzon Street. 4 British Railways. The First 15 Years. Wild Swan Publications. (Not yet published).

- Kirkman, Richard (2015). Transforming Birmingham New Street. Lily Publications Ltd. (UK). ISBN 9781907945915. OCLC 927826418.

- Norton, Mark, Birmingham New Street Station Through Time. Amberley, 2013. ISBN 978-1-4456-1095-5.

- Smith, Donald J., New Street Remembered: The story of Birmingham's New Street Station 1854-1967 in words and pictures. Barbryn Press, 1984. ISBN 0-906160-05-7.

- Upton, Chris, A History of Birmingham, Phillimore 1997. ISBN 0-85033-870-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Birmingham New Street railway station. |

- New Street - New Start

- Birmingham New Street, on Warwickshire Railways Photographs and information on the Victorian Station.

- 1890 Ordnance Survey map of the station

- Rail Around Birmingham and the West Midlands: Birmingham New Street station

- Building a model of Birmingham New Street station

- 1967 ATV report on station rebuilding and opening

- 1994 video of Don's Miniature New Street