Gottfried Reinhold Treviranus (politician)

Gottfried Reinhold Treviranus (20 March 1891, Schieder, Germany – 7 June 1971 Florence, Italy) was a German politician from the Conservative People's Party and a Reichsminister in both of Chancellor Heinrich Brüning's cabinets. In the first he was Minister for Occupied Areas (March – October 1930) and then Minister without Portfolio (October 1930 – October 1931); in the second (October 1931 – May 1932), he served as Minister of Transport.

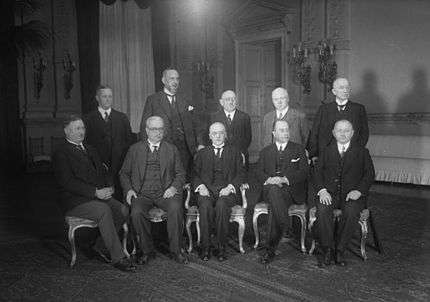

NOTE: CP: Centre Party D: Democrat DPP: German People's Party BPP:Bavarian People's Party CPP: Conservative People's Party EP: Economic Party

Early life

He was the son of a German father and a Scottish mother. After graduation, he became an officer in the Imperial German Navy from 1912 to 1918, holding the rank of lieutenant commander. After leaving the navy, he studied agriculture and in 1921 became director of the Chamber of Agriculture. He was married to Elisabeth Dryander, a travel writer.

Career

Party politician (1924 to 1930)

In 1924, Treviranus supported the German National People's Party (DNVP) and was responsible for the Free State of Lippe. As a representative of the moderate wing of the DNVP he rejected the extreme right led by Alfred Hugenberg who became party president in 1928. In the summer of 1929, Treviranus together with Hans Schlange-Schöningen was one of two prominent DNVP Reichstag deputies resigned from the party's caucus in protest against the Young Plan referendum bill which they called irresponsible in the extreme, to be joined shortly afterwards by the former chairman Count Kuno von Westarp and other 20 DNVP MRDs leaving the party and forming the more moderate Conservative People's Party.[1]

Treviranus politically supported a center-right Government coalition. His goal was to align the CPP coalition with the moderate right. The center-right alliance should conduct comprehensive reforms. With this objective, Treviranus had built close relationships and had good contacts.

Treviranus has played a significant role in the development of Brüning's government in March 1930. In December 1929 he had participated in preliminary discussions with Brüning, Schleicher, Defence Minister Wilhelm Gröner and President Hindenburg's State Secretary Otto Meissner, at the house of his national conservative party friend Friedrich Wilhelm Freiherr von Willisen.[2] Hindenburg gave Brüning the task of building a Cabinet that would govern without the Social Democrats (SPD).[3]

Government Minister (1930 to 1932)

Treviranus' first position in the new government was as Minister for the Occupied Territories, being those parts of the Rhineland still under French and Belgian occupation following World War I. After the occupation forces were reduced following the Young Plan in June 1930 he became Minister without Portfolio and he liaised with industry for Hindenburg and Brüning.

Before the General Election of 1930, Treviranus, in co-operation with politically influential military leaders, tried to re-organise the party system. He negotiated forming a loose middle-class electoral alliance to secure a majority for Brüning. This was funded by generous donations from big business but it was not successful[4]

From 9 October 1931 to 30 May 1932 he served in Brüning's second cabinet as Minister of Transport.

The Government adopted a right wing nationalist stance during election campaigns and also at Cabinet meetings. When French Foreign Minister Aristide Briand submitted a plan for a European Union it was rejected by the entire Cabinet, and Treviranus said that the plan as an attack on the current German foreign policy at that time. In Cabinet meetings he pushed to get the Versailles Treaty revised.[5][6][7][8]

As Reich Commissioner for Eastern Germany, he was not successful in saving the country from bankruptcy and after this failure he resigned in August 1931.[9][10]

The Brüning government went through a crisis in autumn 1931 with a worsening economic situation. Treviranus once again liaised between businesses and the Government. On behalf of Brüning, he advised the major Ruhr industrialists Paul Reusch and Fritz Springorum not to collaborate with the National Socialists and German nationalists. However, the Government fell when embarrassing documents about the behaviour of industry and the banks during the crisis came to light.[11] In the parliamentary elections of 31 July 1932, Treviranus lost his seat as did his conservative People's Party. Treviranus went into business; he was chairman of the Upper Silesian Bata shoe factory. His political career was over at the age of 41.[12]

Escape and emigration

On 30 June 1934, Treviranus narrowly escaped arrest and probably death. This was part of the "Röhm putsch", one of the political purges in the early summer of 1934. While in exile, he recalled that in the early afternoon of 30 June, a large number of police and SS men entered his house. He and his daughter were playing tennis in the garden when she cried out "front of house full of Nazis!" He got away by jumping over the garden fence, and climbed into his car which had the key already in the ignition and drove away at high speed. Five rifle shots fortunately missed. For several days he was hidden by friends, and then helped into the Netherlands by the same person who had helped Heinrich Brüning to flee. It is not clear who put Treviranus' name on the list of persons to be arrested but there is evidence that he was hated by Hitler personally.[13]

After a few days stay in the Netherlands, he went to Great Britain. He met many well-known politicians including Churchill and Anthony Eden, at whose behest, he was asked about the character of Hitler and the Nazi movement. He warned of Hitler's aggressive expansion plan. He was formally expatriated in 1939 by the German Reich and at the outbreak of war went to Canada where he worked as a farmer.

Later years (1945 to 1971)

After 1945, Treviranus advised America on the allocation of loans to German companies as part of the Marshall Plan. In 1949, he returned to Germany. In the 1950s, his name became associated with a gambling scandal. In the 1960s, he worked as a defence lobbyist in Bonn. He died in 1971 during a stay in Florence.

References

- ↑ Wheeler-Bennett, John The Nemesis of Power, London: Macmillan, 1967 page 209.

- ↑ Johannes Hürter: Wilhelm Groener. Defence Minister at the end of the Weimar Republic R Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 1993, p.242

- ↑ Hermann Pünder: Politics in the Reich Chancellery. Records from the years 1929-1932. German publishing house, Stuttgart 1961, p.46

- ↑ Reinhard Neebe: Business, government and the Nazi Party from 1930 to 1933. Paul Silverberg and the National Federation of German Industries in the crisis of the Weimar Republic. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen, 1981, pp.254f.

- ↑ Files of the Reich Chancellery - the Brüning cabinets I and II (1930-1932). Volume 1 Edit. v. Tilman Koops, Boldt, Boppard on the Rhine 1982, No.104

- ↑ Hermann Graml: Between Stresemann and Hitler. The foreign policy of the presidential Brüning, Papen and Schleicher. R. Oldenbourg publishing house, Munich 2001, pp. 52-54

- ↑ Akten der Reichskanzlei. Die Kabinette Brüning I und II (1930–1932). Vol 1, bearb. v. Tilman Koops, Boldt, Boppard am Rhein 1982, No.180]

- ↑ Hans Luther: Vor dem Abgrund 1930–1933. Reichsbankpräsident in Krisenzeiten. Propyläen Verlag, Berlin 1964, S.162

- ↑ Akten der Reichskanzlei. Die Kabinette Brüning I und II (1930–1932) Vol 1 , bearb. v. Tilman Koops, Boldt, Boppard am Rhein 1982, S.XLIV

- ↑ Harold James: Deutschland in der Weltwirtschaftskrise 1924–1936 (Germany in the Worldwide Economic Crisis 1924-36) Deutsche Verlagsanstalt, Stuttgart 1988, S.266f

- ↑ Reinhard Neebe: Großindustrie, Staat und NSDAP 1930–1933. Paul Silverberg und der Reichsverband der Deutschen Industrie in der Krise der Weimarer Republik. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1981, S.107

- ↑ Horst Möller: Gottfried Reinhold Treviranus. Ein Konservativer zwischen den Zeiten. Horst Möller und Andreas Wirsching: Aufklärung und Demokratie. Historische Studien zur politischen Vernunft. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 2003, S.241

- ↑ Dieser nannte Treviranus etwa "ein[en] Schuft" und behauptete: "So ein marxistischer (sic!) kleiner Prolet ist in einer Welt groß geworden, die er gar nicht begriffen hat", siehe Werner Jochmann (Hrsg.): Monologe aus dem Führerhauptquartier. Hamburg 1980, S.248