Goliad, Texas

| Goliad, Texas | |

|---|---|

| City | |

|

Historic district of downtown Goliad; the Von Dohlen Building is named for an early settler. | |

| Motto: "Birthplace of Texas Ranching"[1] | |

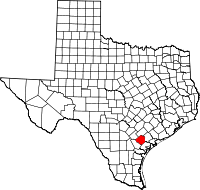

Location of Goliad, Texas | |

| Coordinates: 28°40′N 97°24′W / 28.667°N 97.400°WCoordinates: 28°40′N 97°24′W / 28.667°N 97.400°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Texas |

| County | Goliad |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1.57 sq mi (4.07 km2) |

| • Land | 1.56 sq mi (4.05 km2) |

| • Water | 0.004 sq mi (0.01 km2) |

| Elevation | 164 ft (50 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 1,908 |

| • Density | 1,219/sq mi (470.6/km2) |

| Time zone | Central (CST) (UTC-6) |

| • Summer (DST) | CDT (UTC-5) |

| ZIP code | 77963 |

| Area code(s) | 361 |

| FIPS code | 48-30080[2] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1358133[3] |

| Website |

www |

Goliad (/ˈɡoʊliæd/ GOH-lee-ad) is a city in Goliad County, Texas, United States. It had a population of 1,908 at the 2010 census.[4] Founded on the San Antonio River, it is the county seat of Goliad County.[5] It is part of the Victoria, Texas, Metropolitan Statistical Area.

History

Spain

In 1747, the Spanish government sent José de Escandón to inspect the northern frontier of its North American colonies, including Spanish Texas. In his final report, Escandón recommended the Presidio La Bahía be moved from its Guadalupe River location to the banks of the San Antonio River, so it could better assist settlements along the Rio Grande.[6] Both the presidio and the mission which it protected, Mission Nuestra Señora del Espíritu Santo de Zúñiga, moved to their new location sometime around October 1749. Escandón proposed that 25 Mexican families be relocated near the presidio to form a civilian settlement, but he was unable to find enough willing settlers.[7]

With the conclusion of the Seven Years' War in 1763, France ceded Louisiana and its Texas claims to Spain.[8] With France no longer a threat to the Crown's North American interests, the Spanish monarchy commissioned the Marquis de Rubi to inspect all of the presidios on the northern frontier of New Spain and make recommendations for the future.[9] Rubi recommended that several presidios be closed, but that La Bahia be kept and rebuilt in stone. La Bahia was soon "the only Spanish fortress for the entire Gulf Coast from the mouth of the Rio Grande to the Mississippi River".[10] The presidio was at the crossroads of several major trade and military routes. It quickly became one of the three most important areas in Texas, alongside Béxar and Nacogdoches.[10] A civil settlement, then known as La Bahia, soon developed near the presidio. By 1804, the settlement had one of only two schools in Texas.[11]

In early August 1812, during the Mexican War of Independence, Mexican revolutionary Bernardo Gutiérrez de Lara and his recruits, called the Republican Army of the North, invaded Texas.[12] In November the invaders captured Presidio La Bahia.[13] For the next four months, Texas governor Manuel María de Salcedo laid siege to the fort.[14] Unable to win a decisive victory, Salcedo lifted the siege on February 19, 1813, and turned toward San Antonio de Bexar.[15] The rebels controlled the presidio until July or August 1813, when José Joaquín de Arredondo led royalist troops in retaking all of Texas.[16] Henry Perry, a member of the Republican Army of the North, led forces back to Texas in 1817 and attempted to recapture La Bahia. The Mexicans reinforced the presidio with soldiers from San Antonio, and defeated Perry's forces on June 18 near Coleto Creek.[16]

The area was invaded again in 1821. The United States and Spain had signed the Adams–Onís Treaty in 1819, which ceded all US territorial claims on the Texas area to Spain. On October 4, the Long Expedition (with 52 members) captured La Bahia. Four days later, Colonel Ignacio Pérez arrived with troops from Bexar, and Long surrendered.[17] By the end of 1821, Mexico had achieved its independence from Spain, and Texas became part of the newly created country.[18]

Mexico

In 1829, the name of the Mexican Texas village of La Bahía was changed to "Goliad", believed to be an anagram of Hidalgo (omitting the silent initial "H"), in honor of the patriot priest Miguel Hidalgo, the father of the Mexican War of Independence.[19]

On October 9, 1835, in the early days of the Texas Revolution, a group of Texans attacked the presidio in the Battle of Goliad. The Mexican garrison quickly surrendered, leaving the Texans in control of the fort. The first declaration of independence of the Republic of Texas was signed here on December 20, 1835. Texans held the area until March 1836, when their garrison under Colonel James Fannin was defeated at the nearby Battle of Coleto. Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, then President of Mexico, ordered that all survivors were to be executed. On Palm Sunday, March 27, 1836, in what was later called the Goliad Massacre, 303 were marched out of the fort to be executed, and 39 were executed inside the presidio (20 prisoners were spared because they were either physicians or medical attendants); 342 men were killed and 28 escaped.[20]

The famous Mexican General Ignacio Zaragoza was born in Goliad in 1829. He commanded the forces resisting the French Army in the Battle of Puebla, now celebrated as Cinco de Mayo on May 5, 1862.[21]

The Texas gunfighter King Fisher lived for a time in Goliad before moving to Eagle Pass in Maverick County, Texas.

1902 tornado

The 1902 Goliad tornado devastated the town, killing 114 people, including Sheriff Robert Shaw, and injuring at least 225. It is tied for the deadliest tornado in Texas history and the 10th-deadliest in the United States.[22] Dr. Louis Warren Chilton, a young doctor whose wife was injured and whose daughter was lifted in the tornado funnel but survived, set up a temporary hospital and morgue in the courthouse. The Dr. L.W. and Martha E.S. Chilton House was built starting in June and included an underground shelter.[23]

Geography

Goliad is located near the center of Goliad County at 28°40′N 97°24′W / 28.667°N 97.400°W (28.669, -97.392).[24] U.S. Route 59 passes through the center of town as Pearl Street, leading northeast 26 miles (42 km) to Victoria and southwest 29 miles (47 km) to Beeville. U.S. Route 183 (Jefferson Street) crosses US 59 northeast of the original center of town; US 183 leads north 31 miles (50 km) to Cuero and south 26 miles (42 km) to Refugio. Goliad is 91 miles (146 km) southeast of San Antonio and 68 miles (109 km) north of Corpus Christi.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 1.6 square miles (4.1 km2), of which 0.004 square miles (0.01 km2), or 0.28%, are water.[4] The San Antonio River flows from west to east along the southern border of the city; it is a tributary of the Guadalupe River, joining it just before their mouth at San Antonio Bay.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1880 | 885 | — | |

| 1930 | 1,424 | — | |

| 1940 | 1,446 | 1.5% | |

| 1950 | 1,584 | 9.5% | |

| 1960 | 1,782 | 12.5% | |

| 1970 | 1,709 | −4.1% | |

| 1980 | 1,990 | 16.4% | |

| 1990 | 1,946 | −2.2% | |

| 2000 | 1,975 | 1.5% | |

| 2010 | 1,908 | −3.4% | |

| Est. 2016 | 1,981 | [25] | 3.8% |

As of the census[2] of 2000, 1,975 people, 749 households, and 518 families resided in the city. The population density was 1,294.3 people per square mile (498.4/km²). There were 877 housing units at an average density of 574.7 per square mile (221.3/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 75.44% White, 6.08% African American, 0.35% Native American, 0.61% Asian, 14.99% from other races, and 2.53% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 49.72% of the population.

Of the 749 households, 33.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 51.7% were married couples living together, 12.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 30.8% were not families. About 28.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 15.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.49 and the average family size was 3.04.

In the city, the population was distributed as 26.3% under the age of 18, 7.2% from 18 to 24, 24.4% from 25 to 44, 21.3% from 45 to 64, and 20.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39 years. For every 100 females, there were 91.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 84.1 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $26,200, and for a family was $33,438. Males had a median income of $28,889 versus $20,167 for females. The per capita income for the city was $13,997. About 19.7% of families and 23.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 31.5% of those under age 18 and 17.6% of those age 65 or over.

Education

The Goliad Independent School District serves Goliad.

Attractions

- The Texas Mile, a weekend motorsports racing festival, used to be held at the Goliad Airport near Berclair, TX. After the US Navy reclaimed the airport as a training field, the festival has been held at an airport in Beeville, Texas.

- Goliad Market Days (held on the second Saturday of every month) is an event where produce, arts and crafts, and other retail items are sold.

- Schroeder Hall is one of Texas most legendary dance halls where legends like George Jones, Merle Haggard, Willie Nelson, Ray Price and many others often performed. The hall is still presenting some of the biggest names in country music today as it has for generations.

Notable residents

Climate

The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Goliad has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps.[27]

References

- ↑ "City of Goliad Texas". City of Goliad Texas. Retrieved October 19, 2012.

- 1 2 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 11 September 2013. Retrieved 31 January 2008.

- ↑ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 25 October 2007. Retrieved 31 January 2008.

- 1 2 "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Goliad city, Texas". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved March 14, 2017.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on 31 May 2011. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- ↑ Roell (1994), p. 13

- ↑ Roell (1994), p. 14

- ↑ Weber (1992), p. 198

- ↑ Chipman (1992), p. 173

- 1 2 Roell (1994), p. 15

- ↑ Roell (1994), p. 19

- ↑ Almaráz (1971), p. 159

- ↑ Almaráz (1971), p. 164

- ↑ Roell (1994), p. 20

- ↑ Almaráz (1971), p. 168

- 1 2 Roell (1994), p. 21

- ↑ Roell (1994), p. 23

- ↑ Weber (1992), p. 300

- ↑ Jeri Robison Turner, "GOLIAD, TX," Handbook of Texas Online (http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/hjg05), (Texas State Historical Association), accessed 16 April 2011.

- ↑ Hardin (1994), p. 174

- ↑ "ZARAGOZA, IGNACIO SEGUIN," Handbook of Texas Online (http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fza04) (Texas State Historical Association), accessed 15 April 2011.

- ↑ Texas State Historical Commission, Goliad Tornado of 1902 Historical Marker

- ↑ Mary Burns and Mary Dillman (February 1998). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Dr. L.W. and Martha E.S. Chilton House". National Archives. (accessible by searching within National Archives Catalog)

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 12 February 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- ↑ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved June 9, 2017.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on May 12, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ Climate Summary for Goliad, Texas

- Almaráz, Félix D., Jr. (1971), Tragic Cavalier: Governor Manuel Salcedo of Texas, 1808–1813 (2nd ed.), College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, ISBN 0-89096-503-X

- Chipman, Donald E. (1992), Spanish Texas, 1519–1821, Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, ISBN 0-292-77659-4

- Hardin, Stephen L. (1994), Texian Iliad – A Military History of the Texas Revolution, Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, ISBN 0-292-73086-1, OCLC 29704011

- Davenport, Harbert; Roell, Craig H. "GOLIAD MASSACRE". Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- Roell, Craig H. (1994), Remember Goliad! A History of La Bahia, Fred Rider Cotten Popular History Series (9), Austin, TX: Texas State Historical Association, ISBN 0-87611-141-X

- Weber, David J. (1992), The Spanish Frontier in North America, Yale Western Americana Series, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-05198-0

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Goliad, Texas. |

- City of Goliad official website

- Handbook of Texas Online article

- The Texas Mile