St Ives, Cambridgeshire

| St Ives | |

|---|---|

|

Crown Street | |

St Ives | |

| St Ives shown within Cambridgeshire | |

| Area | 10.88 km2 (4.20 sq mi) [1] |

| Population | 16,384 (2011 Census) |

| • Density | 1,506/km2 (3,900/sq mi) |

| OS grid reference | TL305725 |

| • London | 90 km (56 mi) South |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | ST. IVES |

| Postcode district | PE27 |

| Dialling code | 01480 |

| Police | Cambridgeshire |

| Fire | Cambridgeshire |

| Ambulance | East of England |

| EU Parliament | East of England |

| UK Parliament | |

St Ives is a market town and civil parish in Cambridgeshire, England.[2] St Ives lies about 5 miles (8 km) east of Huntingdon and 12 miles (19 km) north-west of the city of Cambridge. St Ives is situated within the non-metropolitan district of Huntingdonshire, which covers a similar area to the historic county of the same name.

History

Previously called Slepe, its name was changed to St Ives after the body, claimed to be that of a Persian bishop, of Saint Ivo (not to be confused with Ivo of Kermartin), was found buried in the town in about 1001/2.

In 1085 William the Conqueror ordered that a survey should be carried out across his kingdom to discover who owned which parts and what it was worth. The survey took place in 1086 and the results were recorded in what, since the 12th century, has become known as the Domesday Book. Starting with the king himself, for each landholder within a county there is a list of their estates or manors; and, for each manor, there is a summary of the resources of the manor, the amount of annual rent that was collected by the lord of the manor both in 1066 and in 1086, together with the taxable value.[3]

St Ives was listed in the Domesday Book in the Hundred of Hurstingstone in Huntingdonshire; the name of the settlement was written as Slepe in the Domesday Book.[4] In 1086 there was just one manor at St Ives; the annual rent paid to the lord of the manor in 1066 had been £20 and the rent had fallen to £18. 25 in 1086.[5]

The Domesday Book does not explicitly detail the population of a place but it records that there were 64 households at St Ives.[5] There is no consensus about the average size of a household at that time; estimates range from 3.5 to 5.0 people per household.[6] Using these figures then an estimate of the population of St Ives in 1086 is that it was within the range of 224 and 320 people.

The Domesday Book uses a number of units of measure for areas of land that are now unfamiliar terms, such as hides and ploughlands. In different parts of the country, these were terms for the area of land that a team of eight oxen could plough in a single season and are equivalent to 120 acres (49 hectares); this was the amount of land that was considered to be sufficient to support a single family. By 1086, the hide had become a unit of tax assessment rather than an actual land area; a hide was the amount of land that could be assessed as £1 for tax purposes. The survey records that there were 29. 5 ploughlands at St Ives in 1086.[5] In addition to the arable land, there was 60 acres (24 hectares) of meadows and 1,892 acres (766 hectares) of woodland at St Ives.[5]

The tax assessment in the Domesday Book was known as geld or danegeld and was a type of land-tax based on the hide or ploughland. It was originally a way of collecting a tribute to pay off the Danes when they attacked England, and was only levied when necessary. Following the Norman Conquest, the geld was used to raise money for the King and to pay for continental wars; by 1130, the geld was being collected annually. Having determined the value of a manor's land and other assets, a tax of so many shillings and pence per pound of value would be levied on the land holder. While this was typically two shillings in the pound the amount did vary; for example, in 1084 it was as high as six shillings in the pound. For the manor at St Ives the total tax assessed was twenty geld.[5]

By 1086 there were two churches and two priests at St Ives.

For the past 1,000 years it has been home to some of the biggest markets in the country, and in the thirteenth century it was an important entrepôt, and remains an important market in East Anglia.

Built on the banks of the wide River Great Ouse between Huntingdon and Ely, St Ives has a famous chapel on its bridge. In the Anglo-Saxon era, St Ives's position on the river Great Ouse was strategic, as it controlled the last natural crossing point or ford on the river, 80 kilometres (50 mi) from the sea. The flint reef in the bed of the river at this point gave rise to a ford, which then provided the foundations for the celebrated bridge.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, St Ives was a hub of trade and navigation, and the town had dozens of inns and many bawdy houses . Goods were brought into the town on barges, and livestock rested on the last fattening grounds before delivery to London's Smithfield Market. As the railway network expanded and roads improved, the use of the River Great Ouse declined. It is now mostly used for leisure boats and recreation.

The river Great Ouse at St Ives flooded in 1947, and some parts suffered seriously again at Easter 1998[7] and in January 2003.[8] Extensive flood protection works were carried out on both sides of the river in 2006/2007 at a cost of nearly £9 million. 500 metres (1,600 ft) of brick-clad steel-piling was put into place to protect the town, most noticeably at the Waits where a pleasing plaza has also been created. A further 750 metres (2,460 ft) on the other side of the river protects Hemingford Grey, reducing the yearly risk of flooding from 10% to 1%.[9] Building on the flood plain at St Ives is now discouraged.

Original historical documents relating to St Ives, including the original parish church registers, local government records, maps and photographs, are held by Cambridgeshire Archives and Local Studies at the County Record Office in Huntingdon.

Government

As a civil parish, St Ives has a town council. The town council is elected by the residents of the town who have registered on the electoral roll; like a parish council, a town council is the lowest tier of government in England. A town council is responsible for providing and maintaining a variety of local services including allotments and a cemetery; grass cutting and tree planting within public open spaces such as a village green or playing fields. The town council reviews all planning applications that might affect the town and makes recommendations to Huntingdonshire District Council, which is the local planning authority for St Ives. The town council also represents the views of the residents of the town on issues such as local transport, policing and the environment. The town council raises its own tax to pay for these services, known as the parish precept, which is collected as part of the Council Tax. the town council consists of seventeen councillors and includes a major and a deputy-mayor.[10]

St Ives was in the historic and administrative county of Huntingdonshire until 1965. From 1965, the village was part of the new administrative county of Huntingdon and Peterborough. Then in 1974, following the Local Government Act 1972, St Ives became a part of the county of Cambridgeshire.

The second tier of local government is Huntingdonshire District Council which is a non-metropolitan district of Cambridgeshire and has its headquarters in Huntingdon. Huntingdonshire District Council has 52 councillors representing 29 district wards.[11] Huntingdonshire District Council collects the council tax, and provides services such as building regulations, local planning, environmental health, leisure and tourism.[12] [11] St Ives has three district wards for Huntingdonshire District Council; St Ives East, St Ives South, and St Ives West.[13] St Ives East and St Ives South are both represented by two district councillors, and St Ives West is represented on the district council by one councillor.[14] District councillors serve for four year terms following elections to Huntingdonshire District Council.

For St Ives the highest tier of local government is Cambridgeshire County Council which has administration buildings in Cambridge. The county council provides county-wide services such as major road infrastructure, fire and rescue, education, social services, libraries and heritage services.[15] Cambridgeshire County Council consists of 69 councillors representing 60 electoral divisions.[16] St Ives is part of the electoral division of St Ives [13] and is represented on the county council by two councillors.[16]

At Westminster St Ives is in the parliamentary constituency of Huntingdon,[13] and elects one Member of Parliament (MP) by the first past the post system of election. St Ives is represented in the House of Commons by Jonathan Djanogly (Conservative). Jonathan Djanogly has represented the constituency since 2001. The previous member of parliament was John Major (Conservative) who represented the constituency between 1983 and 2001. For the European Parliament St Ives is part of the East of England constituency which elects seven MEPs using the d'Hondt method of party-list proportional representation.

Geography

St Ives experienced town planning at a very early date, giving it a spacious Town Centre. Portions of this open space between Merryland and Crown Street were lost to market stalls that turned into permanent buildings. Some of the shops in the town centre are still to the same layout as in Medieval times, one rod in width, the standard length for floor and roof joists. The lanes along the north side of town are believed to follow the layout of the narrow medieval fields, and are slightly S-shaped because of the way ploughs turned at each end. Similar field boundaries can be seen in Warners Park.

Demography

Population

In the period 1801 to 1901 the population of St Ives was recorded every ten years by the UK census. During this time the population was in the range of 2,099 (the lowest was in 1801) and 3,572 (the highest was in 1851).[17]

From 1901, a census was taken every ten years with the exception of 1941 (due to the Second World War).

| Parish |

1911 |

1921 |

1931 |

1951 |

1961 |

1971 |

1981 |

1991 |

2001 |

2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| St Ives | 3,015 | 2,797 | 2,664 | 3,078 | 4,082 | 7,148 | 12,331 | 14,930 | 16,001 | 16,384 |

All population census figures from report Historic Census figures Cambridgeshire to 2011 by Cambridgeshire Insight.[17]

In 2011, the parish covered an area of 2,688 acres (1,088 hectares)[17] and the population density of St Ives in 2011 was 3901 persons per square mile (1505.9 per square kilometre).

Economy

The Monday market takes over the town centre, and is larger in scale on Bank Holidays in May and August. There is a Friday market, and a Farmers' Market on the first and third Saturday every month. The Michaelmas Fair takes over for three days from the second Monday in October, and there is a carnival[18][19] which is the biggest public gathering in Huntingdonshire. The town has a mixture of shops, bars, coffee lounges, a department store and other amenities.

Public houses

As an important market town, St Ives always needed large numbers of public houses: 64 in 1838 (1 for every 55 inhabitants), 60 in 1861, 48 in 1865 and 45 in 1899, although only five of these made the owners a living. As livestock sales diminished, however, so did the need for large numbers of pubs, falling to a low point of 16 in 1962. In that year the Seven Wives on Ramsey Road was opened and, with some openings and closings since, there are 17 today. The pub which has stood on the same site, with the same name, for longest, is the Dolphin, which is over 400 years old. Next oldest is the White Hart, which is pre-1720. Nelson's Head and Golden Lion are at least as old but have not kept the same name and used to be called the Three Tuns and the Red Lion respectively. The existence of a pub on the site of the Robin Hood is also of a similar date, except that it was originally two separate pubs — the Angel and the Swan. The claim of the Royal Oak to date from 1502 cannot be proven since, while a portion at the back is 17th-century (making it physically the oldest portion of any pub in St Ives), the pub name is more recent. The reference is to Charles II's famous escape from Cromwell's Roundheads, and Charles was restored to the throne in 1660.[20]

The Golden Lion was a 19th-century coaching inn.[21] The Official Guide to the Great Eastern Railway referred to it in 1893 as one of two "leading hotels" in St Ives[22] and there are a number of ghost stories associated with the pub.[21][23][24][25]

Landmarks

St Ives Bridge

St Ives Bridge is most unusual in incorporating a chapel, the most striking of only four examples in England. Also unusual are its two southern arches which are a different shape from the rest of the bridge, being rounded instead of slightly gothic. After the dissolution of the monasteries in 1537, the chapel was given to the prior to live in. The lords of the manor of St Ives changed hands several times, as did the chapel. During this period, it was in turn - a private house, a doctors surgery and a pub, called Little Hell. The pub did have a reputation for rowdy behavior and the landlord kept pigs in the basement! The additional two storeys added in the seventeenth century were removed in 1930, due to damage being caused to the foundations. The chapel features colourfully in the historical novel 'Not Just a Whore', by local St Ives resident K M Warwick, where it is described as a fictitious "Bawdy House" (brothel). The bridge was partially rebuilt after Oliver Cromwell knocked down two arches during the English Civil War to prevent King Charles I's troops approaching London from the Royalist base in Lincolnshire. During the war and for some period afterwards, the gap was covered by a drawbridge. The town square contains a statue of Oliver Cromwell erected in 1901. It is one of four statues of Cromwell on public display in Britain, the others being in Parliament Square, outside Wythenshawe Hall and in Warrington.

St Ives Corn Exchange is the home of St Ives Youth Theatre (SIYT).

Holt Island

The eastern or town end of Holt Island is nature reserve, and the western end, opposite the parish church, is a facility for the Sea Scouts. The scout portion contains what was, before the opening of the Leisure Centre, the town's outdoor town swimming pool. The pool was dug in 1913 and closed to the public in 1949.[26] It is now used by the scouts for canoeing and rappelling. In November 1995, the island was the locus of a significant lawsuit and a break-away Scouting Association was prevented from using and developing a claim to it.[27]

Culture and community

The Norris Museum holds a great deal of local history, including a number of books written by its former curator, Bob Burn-Murdoch.[28] After over 30 years of service, Bob Burn-Murdoch retired in December 2012.[29] The Norris Museum was founded by Herbert Norris, who left his lifetime's collection of Huntingdonshire relics to the people of St Ives when he died in 1931.

Sports

There is an indoor recreation centre adjacent to the Burgess Hall and an outdoor recreation centre at the top end of the town. Both have football grounds, and the Colts also play football in Warners Park over the winter. The original swimming pool, fed by the river, is in the middle of Holt Island and is now used for canoeing practice and other activities. St Ives also has a Rugby club on Somersham Road,[30] and a Non-League football club, St Ives Town F.C., which plays at Westwood Road. The St Ives Rowing Club was once captained by John Goldie and has had a number of members who have competed at Olympic and Commonwealth championships.

There is an active swimming club. New members are always welcome, from age 4½ upwards, whatever their swimming ability and can be slotted into (and trained up to) teaching groups, a pre-competitive group, development squads or senior/competitive squads

St Ives has an 18 hole championship golf course, located 1/2 mile east of St Ives on the A1123. It opened in the summer of 2010, replacing the previous 9 hole course on Westwood Road.

Education

St Ives has a main secondary school, St Ivo School. Eastfield nursery and infant school, Westfield Junior school and two primary schools Thorndown and Wheatfields.

Transport

Guided busway

The major section of the world's longest guided busway, using all new construction techniques and technology, connects St Ives directly to Cambridge Science Park on the outskirts of Cambridge[31] along the route of a disused railway line. The same buses continue into the centre of Cambridge along regular roads in one direction and continue to Huntingdon in the other direction. A shorter section of the same busway system operates from the railway station on the far side of Cambridge to Addenbrooke's Hospital and Trumpington.[32] The scheme, budgeted at £116.2 million, opened in summer 2011. Construction of the busway was beset with problems, causing delays; for example, cracks appeared in the structure allowing weeds to grow through. Contractors BAM Nuttall were fined a significant amount of money for each day that the busway completion date was not met.[33]

The St Ives Park & Ride on Meadow Lane is part of the scheme and will open at the same time.[34] A "Green Update" newsletter came out in Winter 2007 with news on conservation work including protection of the Great Crested Newt.[35]

Road

St Ives is just off the A14 road on a particularly congested section of the route from the UK's second city, Birmingham, to the port of Felixstowe and thence to the mainland of Europe[36] This 32-kilometre (20 mi) section of road also links the northern end of the M11 (Cambridge and region) to the M1 and the whole of the North of England and Scotland. A new by-pass is planned for St Ives and Huntingdon, leaving the existing alignment near Swavesey and passing to the south of both market towns.[37] A northern bypass has been under discussion for even longer but is not anticipated any time soon.

Rail and conventional bus

Bus services are provided by Stagecoach in Huntingdonshire and Go Whippet, the former also having its depot near the town. Services to Cambridge and Huntingdon are frequent during the day, though less frequent in the evenings. There are also buses to Somersham, Ramsey and Cambourne.

Between 1847 and 1970 the town was served by St Ives railway station on the Cambridge and Huntingdon railway.[38] The line from Cambridge and the station almost survived the 1963 to 1973 Beeching Axe, but were lost to passenger service in the final stages of the process. Some sections continued to be used for freight until 1993. A campaign to reopen the passenger rail service only ended with the ripping-up of disused track shortly before construction of the Guided Busway. Huntingdon, 7 miles (11 km)) away, has the nearest railway station. Buses using the Busway system provide direct links to both Huntingdon and Cambridge stations.

Religious sites

There are ten places of worship, including the ancient parish church. Many other Christian denominations are also represented, and the town also has a mosque and an Islamic Community Centre.

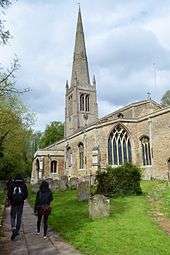

All Saints Church (Church of England) on Church Street has been in the town since AD970 and is one of only two Grade I listed buildings in the town, the other being The Bridge. Originally the parish church of the settlement of Slepe, before St Ives came into existence, it now enjoys a tranquil location at the end of Church Street, situated to the west of the town centre. All Saints, as it stands today, dates largely from the rebuilding of the late 15th century. It was extensively reordered in the late 19th century by Sir Ninian Comper.

The church which dominates the town's market place, is The Free Church (United Reformed Church). This was built in 1864, but was modernised in 1980, moving the worship area upstairs. The Church of the Sacred Heart (Roman Catholic) on Needingworth Road, was originally built by Augustus Pugin in Cambridge, but was dismantled in 1902 and transported by barge to St Ives. The hall at the back was added in about 2001. The current Methodist Church on The Waits opened in 1905. Crossways Church (Assembly of God) meet at Crossways Christian Centre on Ramsey Road. St Ives Christian Fellowship (Partnership) meet at Thorndown Junior School on Hill Rise. The Bridge Church (New Frontiers) meet in a newly renovated former industrial building on the corner of Burrel Road and Marley Road. St Ives Evangelical Christian Church (Evangelical) meet at the Burleigh Hill Community Centre, off Constable Road.

Cultural references

The town name is featured in the anonymous nursery rhyme/riddle "As I was going to St Ives". While sometimes claimed to be St Ives, Cornwall, the man with seven wives, each with seven sacks containing seven cats etc. may have been on his way to (or coming from) the Great Fair at St Ives.[39] On Ramsey Road there is a public house called The Seven Wives, though this is a modern pub with no connection to the ancient rhyme other than the name.[40]

The term tawdry is a St Ives derived word (vying with the rival Ely claim), basically meaning something that is 'cheap and cheerful', and was evolved directly from the St Audrey's Lane cloth market held during the mediaeval and later ages. Made from discarded inferior wool and/or other felt fibres, it was a popular source of cheap material bought by the locals, and those further afield, who flocked to the market in their droves to buy cheap supplies for their own domestic clothing.

The famous war poet Rupert Brooke lived at Grantchester some 32 kilometres (20 mi) away in the same county. In his famous poem "The Old Vicarage, Grantchester" he heaped praise on his own village, but not on the shire town of Cambridge itself, or on the other villages around. Of St Ives he wrote:

| “ | Strong men have blanched and shot their wives, rather than send them to St Ives[41] | ” |

References

- ↑ "2011 Census area information". Retrieved 25 June 2014.

- ↑ Ordnance Survey: Landranger map sheet 153 Bedford & Huntingdon (St Neots & Biggleswade) (Map). Ordnance Survey. 2013. ISBN 9780319231722.

- ↑ Dr Ann Williams, Professor G.H. Martin, eds. (1992). Domesday Book: A Complete Translation. London: Penguin Books. pp. 551–561. ISBN 0-141-00523-8.

- ↑ Dr Ann Williams, Professor G.H. Martin, eds. (1992). Domesday Book: A Complete Translation. London: Penguin Books. p. 1402. ISBN 0-141-00523-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Professor J.J.N. Palmer, University of Hull. "Open Domesday: Place - St Ives". www. opendomesday.org. Anna Powell-Smith. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ↑ Goose, Nigel; Hinde, Andrew. "Estimating Local Population Sizes" (PDF). Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ↑ "1998 Floods in St Ives". Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 6 September 2009.

- ↑ "2003 Floods in St Ives". Retrieved 6 September 2009.

- ↑ "£8. 8m flood defence scheme opened". BBC News. 22 June 2007. Retrieved 6 September 2009.

- ↑ "St Ives Town Council: Councillors". www.stivestowncouncil.gov.uk. St Ives Town Council. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- 1 2 "Huntingdonshire District Council: Councillors". www.huntingdonshire.gov.uk. Huntingdonshire District Council. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ↑ "Huntingdonshire District Council". www.huntingdonshire.gov.uk. Huntingdonshire District Council. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Ordnance Survey Election Maps". www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk. Ordnance Survey. Archived from the original on 20 February 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ↑ "Huntingdonshire District Council: Councillors". www.huntsdc.gov.uk. Huntingdonshire District Council. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ↑ "Cambridgeshire County Council". www.cambridgeshire.gov.uk. Cambridgeshire County Council. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- 1 2 "Cambridgeshire County Council: Councillors". www.cambridgeshire.gov.uk. Cambridgeshire County Council. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Historic Census figures Cambridgeshire to 2011" (xlsx - download). www.cambridgeshireinsight.org.uk. Cambridgeshire Insight. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Burn-Murdoch, Bob (16 October 2008), The Pubs of St Ives (3rd ed.), Friends of the Norris Museum

- 1 2 Stuart Fisher (2013). British River Navigations: Inland Cuts, Fens, Dikes, Channels and Non-tidal Rivers. A&C Black. p. 151. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ↑ Great Eastern Railway (1893). The Official Guide to the Great Eastern Railway. Cassell. p. 271. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ↑ Damien O'Dell (2013). Paranormal Cambridgeshire. Amberley Publishing Limited. p. 53. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ↑ Alan Wood (2013). Military Ghosts. Amberley Publishing Limited. p. 69. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ↑ Dennis William Hauck (2000). The International Directory of Haunted Places. Penguin Group. p. 18. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ↑ "St Ives a new Millenium". St Ives Photo Publication Group. Inchcape. 2002. pp. 8–9. [sic]

- ↑ "SCOUTS FIGHT FOR RIGHT TO ISLAND". Local Government Chronicle. Emap Communications. 19 November 1995. Retrieved 6 November 2008.

- ↑ "Norris Museum". Norris Museum. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ↑ "St Ives museum comes to an end of an era". Hunts Post. 9 August 2012. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ Kirby, Andy. "St Ives Rugby Union Football Club". Stivesrufc.co.uk. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ↑ "Secretary Of State Celebrates Start Of Works On Guided Busway". Cambridgeshire County Council. 5 March 2007. Archived from the original on 6 June 2009. Retrieved 6 September 2009.

- ↑ "The Busway Network". Cambridgeshire County Council. Archived from the original on 16 April 2009. Retrieved 6 September 2009.

- ↑ "Cambridgeshire Guided Busway - Information about the scheme" (PDF). Cambridgeshire County Council. 10 January 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2008. Retrieved 6 September 2009.

- ↑ "Guided Busway Update" (PDF). Cambridgeshire County Council. October 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 6 September 2009.

- ↑ "Guided Busway Green Update - Winter 2007" (PDF). cambridgeshire County Council. 26 November 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 6 September 2009.

- ↑ "Trafficmaster/RAC Foundation Congestion report: Volume 2" (PDF). Trafficmaster plc and RAC Foundation for Motoring. p. 9. Retrieved 6 September 2009.

- ↑ "Ellington to Fen Ditton Improvemebt" (PDF). Highways Agency. November 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 6 September 2009.

- ↑ Catford, Nick. "Station Name:ST. IVES (Huntingdonshire)". www.subbrit.org.uk. Retrieved 29 October 2008.

- ↑ Hudson, Noel (1989), St Ives, Slepe by the Ouse, St Ives Town Council, p. 131, ISBN 978-0-9515298-0-5

- ↑ Indeed in the earliest recorded English version of the riddle, of 1730, there were nine wives. See main article.

- ↑ Brooke, Rupert (May 1912). The Old Vicarage, Grantchester. Café des Westerns, Berlin. Retrieved 21 March 2009.

Further reading

St Ives, Slepe by the Ouse, by Noel Hudson. Black Bear Press, 1989, ISBN 0-9515298-0-3

External links

![]() Media related to St Ives, Cambridgeshire at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to St Ives, Cambridgeshire at Wikimedia Commons