Gods and demons fiction

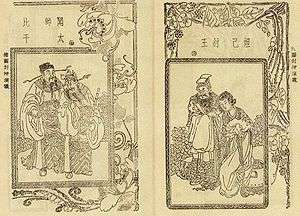

Gods and demons fiction (simplified Chinese: 神魔小说; traditional Chinese: 神魔小說; pinyin: Shénmó Xiǎoshuō) is a subgenre of fantasy fiction that revolves around the deities, immortals, and monsters of Chinese mythology. The term shenmo xiaoshuo, which was coined in the early 20th century by the writer and literary historian Lu Xun, literally means "fiction of gods and demons".[1] Works of shenmo fiction include the novels Journey to the West and The Investiture of the Gods.[2]

History

Shenmo first appeared in the Ming Dynasty as a genre of vernacular fiction,[3] a style of writing based on spoken Chinese rather than Classical Chinese. The roots of the genre are found in traditional folktales and legends.[4] Plot elements like the use of magic and alchemy were derived from Chinese mythology and religion, including Taoism and Buddhism, popular among Ming intellectuals.[5]

The Sorcerer's Revolt (Pingyao zhuan) is an early gods and demons novel written by Luo Guanzhong.[6][7] In the story, Wang Ze begins a rebellion against the government with the aid of magic.[8] The Four Journeys (Siyouji) is another early shenmo work composed of four novels and published during the dynasty as a compilation of folk stories.[9] The Story of Han Xiangzi (Han xiangzi quanzhuan), a Taoist novel from the same period, also shares this supernatural theme but contains heavier religious overtones.[10]

The most well known examples of shenmo fiction are Journey to the West (Xiyouji) and The Investiture of the Gods (Fengshen yanyi).[11] Journey to the West in particular is considered by Chinese literary critics as the chef-d'oeuvre of shenmo novels.[12] The novel's authorship is attributed to Wu Cheng'en and was first published in 1592 by Shitedang, a Ming publishing house.[13] The popularity of Journey to the West inspired a series of shenmo copycats that borrowed plot elements from the book.[14]

Comic shenmo of the Ming and Qing dynasties

Later works of gods and demons fiction drifted away from the purely fantastical themes of novels like Journey to the West. Shenmo novels were still ostensibly about monsters and gods, but carried more humanistic themes. During the late Ming Dynasty and early Qing Dynasty, a subgenre of comedic shenmo had emerged.[15]

The grotesque exposés of the Qing dynasty (qiangze xiaoshuo) reference the supernatural motifs of shenmo xiaoshuo, but in the Qing exposés, the division between the real and unreal is less clear cut. The supernatural is placed outside of conventional fantasy settings and presented as a natural part of a realistic world, bringing about its grotesque nature.[16][17] This trait is embodied in the Journey to the West and other shenmo parodies of the late Qing dynasty.[18] In A Ridiculous Journey to the West (Wuli qunao zhi xiyouji) by Wu Jianwen, the protagonist Bare-Armed Gibbon, a more venal version of Sun Wukong, aids the Vulture King once he is unable to wring any money out of a penniless fish that the vulture had caught and dropped in a puddle.[19]

The monkey returns in another Wu Jianwen story, Long Live the Constitution (Lixian wansui), and bickers with other characters from Journey to the West over a constitution for Heaven.[20] The four main characters of Journey to the West, the monkey, Xuanzang, Zhu Bajie, and Sha Wujing, travel to modern Shanghai in the New Journey to the West (Xin xiyouji) by Lengxue. In Shanghai, they mingle with prostitutes, suffer from drug addiction, and play games of mahjong. Journey to the West was not the only gods and demons novel lampooned. New Investiture of the Gods (Xin Fengshenzhuan) is a parody of Investiture of the Gods by Dalu that was published as a guji xiaoshuo comedy.[21]

Novels in this subgenre include an expanded revision of The Sorcerer's Revolt, What Sort of Book Is This?, Romance of Devil Killing (Zhanggui zhuan), and Quelling the Demons (Pinggui zhuan). Instead of focusing only on a supernatural realm, shenmo comedies used fantasy as a social commentary on the follies of the human world.[22] Lu Xun theorized that the shenmo genre shaped the satirical works later written in the Qing Dynasty.[23] The genre also influenced the science fantasy novels of the late Qing.[24]

20th century

Shenmo literature declined in the early 20th century. The generation of writers following the May Fourth Movement rejected fantasy in favor of literary realism influenced by the trends of 19th-century European literature.[25] Chinese writers regarded fantasy genres like shenmo as superstitious and a product of a feudal society. Stories of gods and monsters were seen as an obstacle to the modernization of China and scientific progress.[26] The writer Hu Shih wrote that the spells and magical creatures of Chinese fiction were more harmful to the Chinese people than the germs discovered by Louis Pasteur. Stories of the supernatural were denounced during the Cultural Revolution, an era when "Down with ox-ghosts and snake-spirits" was a popular Communist slogan.[27]

Shenmo and other fantasy genres experienced a revival in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and, later, in Mainland China after the Cultural Revolution ended.[28] Having returned to Chinese popular culture, fantasy has populated film, television, radio, and literature. Contemporary writers frequently use supernatural themes to accentuate the otherworldly atmosphere of their works.[29]

Origin of the term

The term shenmo xiaoshuo was coined by the writer and literary historian Lu Xun in his book A Brief History of Chinese Fiction (1930), which has three chapters on the genre. The literary historian Mei Chun translates Lu Xun's term as "supernatural/ fantastic".[30] The term was adopted as a convention by the generations of Chinese literary critics that followed him.[31] In their 1959 translation of Lu Xun's book, Gladys Yang and Yang Xianyi translate shenmo as "Gods and Devils".[32][33] Lin Chin, a historian of Chinese literature, categorized the fantasy novels of the Ming dynasty as shenguai xiaoshuo, "novels of gods and strange phenomenon".[34]

Notes

- ↑ Chun 2011, p. 120

- ↑ Wang 1997, p. 201

- ↑ Lu 1959, p. 198

- ↑ Lu 1959, p. 199

- ↑ Lu 1959, p. 198

- ↑ Lu 1959, p. 198

- ↑ Lu 1959, p. 419

- ↑ Lu 1959, pp. 176–177

- ↑ Lu 1959, p. 190

- ↑ Yang 2008, p. xxxii

- ↑ Wang 1997, p. 201

- ↑ Yu 2008, p. 44

- ↑ Chun 2011, p. 120

- ↑ Chun 2011, p. 120

- ↑ Wang 1997, p. 205

- ↑ Wang 1997, p. 183

- ↑ Wang 1997, p. 202

- ↑ Wang 1997, p. 204

- ↑ Wang 1997, pp. 202–203

- ↑ Wang 1997, p. 204

- ↑ Wang 1997, p. 204

- ↑ Wang 1997, p. 205

- ↑ Wang 2004, p. 264

- ↑ Wang 1997, p. 201

- ↑ Wang 2004, p. 264

- ↑ Wang 2004, p. 264

- ↑ Wang 2004, p. 265

- ↑ Wang 2004, p. 265

- ↑ Wang 2004, p. 266

- ↑ Chun 2011, p. 120 note 28.

- ↑ Yu 2008, p. 44

- ↑ Lu 1959, pp. 198–231

- ↑ Yang 2008, p. xxxi

- ↑ Yang 2008, p. xxxii

References and further reading

- Wang, David Der-wei (1997). Fin-de-siècle Splendor: Repressed Modernities of Late Qing Fiction, 1849-1911. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2845-4.

- Wang, David Der-wei (2004). The Monster that is History: History, Violence, and Fictional Writing in Twentieth-century China. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-93724-6.

- Chun, Mei (2011). The Novel and Theatrical Imagination in Early Modern China. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-19166-2.

- Lu, Hsün (1959). A Brief History of Chinese Fiction. Translated by Hsien-yi Yang; Gladys Yang. Foreign Language Press. ISBN 978-7-119-05750-7.

- Yang, Erzeng (2008). The Story of Han Xiangzi: The Alchemical Adventures of a Daoist Immortal. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-80194-0.

- Yu, Anthony (2008). "The Formation of Fiction in the "Journey to the West"". Asia Minor. Academia Sinica. 21 (1): 15–44. JSTOR 41649940.