Protein isoform

A protein isoform, or "protein variant"[1] is a member of a set of highly similar proteins that perform the same or similar biological roles. A set of protein isoforms may be formed from alternative splicings or other post-translational modifications of a single gene. Through RNA splicing mechanisms, mRNA has the ability to select different protein-coding segments (exons) of a gene, or even different parts of exons from RNA to form different mRNA sequences. Each unique sequence produces a specific form of a protein. A set of protein isoforms may also result from a set of closely related genes that evolved from a single gene in the past.

The discovery of isoforms could explain the discrepancy between the small number of protein coding regions genes revealed by the human genome project and the large diversity of proteins seen in an organism: different proteins encoded by the same gene could increase the diversity of the proteome. Isoforms at the DNA level are readily characterized by cDNA transcript studies. Many human genes possess confirmed alternative splicing isoforms. It has been estimated that ~100,000 ESTs can be identified in humans.[2] Isoforms at the protein level can manifest in deletion of whole domains or shorter loops, usually located on the surface of the protein.[3]

Definition

One single gene has the ability to produce multiple proteins.[4][5] All these proteins are different both in structure and composition and this process is regulated by alternative splicing of mRNA and have a large impact in proteome diversity. The specificity of produced proteins is derived by protein structure/function, development stage and even the cell type.[4][5] It becomes more complicated when a protein has multiple subunits and each subunit has multiple isoforms.

For example, the 5' AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), an enzyme, which performs different roles in human cells, has 3 subunits:[6]

- α, catalytic domain, has two isoforms: α1 and α2 which are encoded from PRKAA1 and PRKAA2

- β, regulatory domain, has two isoforms: β1 and β2 which are encoded from PRKAB1 and PRKAB2

- γ, regulatory domain, has three isoforms: γ1, γ2, and γ3 which are encoded from PRKAG1, PRKAG2, and PRKAG3

In human skeletal muscle, the preferred form is α2β2γ1.[6] But in the human liver, the most abundant form is α1β2γ1.[6]

Mechanism

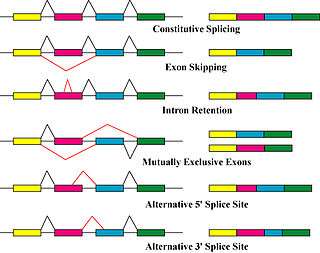

Alternative splicing is a post-transcriptional modification process which is the major molecular mechanism that contributes to the protein diversity.[5]

It was found that the spliceosome, a large ribonucleoprotein, is the place where the RNA cleavage and ligation proceeds for the removal of non protein coding segments or introns.[7] It requires five subunits, U1,U2, U4/U6 and U5, to form an active spliceosome.[7]

There are three main components of a common alternative splicing mechanism:[7]

- cis-acting regulatory sequences

- RNA-binding protein splicing factors

- RNA-RNA base pairing

In short, during the transcription process, mRNA may include (enhance) or exclude (silent) one or multiple exons of a gene.[5][7]

Related Concept

Glycoform

A glycoform is an isoform of a protein that differs only with respect to the number or type of attached glycan. Glycoproteins often consist of a number of different glycoforms, with alterations in the attached saccharide or oligosaccharide. These modifications may result from differences in biosynthesis during the process of glycosylation, or due to the action of glycosidases or glycosyltransferases. Glycoforms may be detected through detailed chemical analysis of separated glycoforms, but more conveniently detected through differential reaction with lectins, as in lectin affinity chromatography and lectin affinity electrophoresis. Typical examples of glycoproteins consisting of glycoforms are the blood proteins as orosomucoid, antitrypsin, and haptoglobin. An unusual glycoform variation is seen in neuronal cell adhesion molecule, NCAM involving polysialic acids, PSA.***

Examples

- G-actin: despite its conserved nature, it has a varying number of isoforms (at least six in mammals).

- Creatine kinase, the presence of which in the blood can be used as an aid in the diagnosis of myocardial infarction, exists in 3 isoforms.

- Hyaluronan synthase, the enzyme responsible for the production of hyaluronan, has three isoforms in mammalian cells.

- UDP-glucuronosyltransferase, an enzyme superfamily responsible for the detoxification pathway of many drugs, environmental pollutants, and toxic endogenous compounds has 16 known isoforms encoded in the human genome.[8]

- G6PDA: normal ratio of active isoforms in cells of any tissue is 1:1 shared with G6PDG. This is precisely the normal isoform ratio in hyperplasia. Only one of these isoforms is found during neoplasia.[9]

See also

References

- ↑ Smith, Lloyd M; Kelleher, Neil L; Linial, Michal; Goodlett, David; Langridge-Smith, Pat; Goo, Young Ah; Safford, George; Bonilla*, Leo; Kruppa, George. "Proteoform: a single term describing protein complexity". Nature Methods. 10 (3): 186–187. PMC 4114032

. PMID 23443629. doi:10.1038/nmeth.2369.

. PMID 23443629. doi:10.1038/nmeth.2369. - ↑ Brett, D; Pospisil, H; Valcárcel, J; Reich, J; Bork, P (2002). "Alternative splicing and genome complexity". Nature Genetics. 30 (1): 29–30. PMID 11743582. doi:10.1038/ng803.

- ↑ Kozlowski, L.; Orlowski, J.; Bujnicki, J. M. (2012). "Structure Prediction for Alternatively Spliced Proteins". Alternative pre-mRNA Splicing. p. 582. ISBN 9783527636778. doi:10.1002/9783527636778.ch54.

- 1 2 Athena Andreadis; Maria E. Gallego; Nadal-Ginard, Bernardo (1987-01-01). "Generation of Protein Isoform Diversity by Alternative Splicing: Mechanistic and Biological Implications". Annual Review of Cell Biology. 3 (1): 207–242. PMID 2891362. doi:10.1146/annurev.cb.03.110187.001231.

- 1 2 3 4 R E Breitbart; A Andreadis; Nadal-Ginard, B. (1987-01-01). "Alternative Splicing: A Ubiquitous Mechanism for the Generation of Multiple Protein Isoforms from Single Genes". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 56 (1): 467–495. PMID 3304142. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.002343.

- 1 2 3 Dasgupta, Biplab; Chhipa, Rishi Raj (2016-03-01). "Evolving Lessons on the Complex Role of AMPK in Normal Physiology and Cancer". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 37 (3): 192–206. ISSN 0165-6147. PMC 4764394

. PMID 26711141. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2015.11.007.

. PMID 26711141. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2015.11.007. - 1 2 3 4 Lee, Yeon; Rio, Donald C. (2015-01-01). "Mechanisms and Regulation of Alternative Pre-mRNA Splicing". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 84 (1): 291–323. PMC 4526142

. PMID 25784052. doi:10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-034316.

. PMID 25784052. doi:10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-034316. - ↑ Barre L, Fournel-Gigleux S, Finel M, Netter P, Magdalou J, Ouzzine M (March 2007). "Substrate specificity of the human UDP-glucuronosyltransferase UGT2B4 and UGT2B7. Identification of a critical aromatic amino acid residue at position 33". FEBS J. 274 (5): 1256–64. PMID 17263731. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05670.x.

- ↑ Pathoma, Fundamentals of Pathology

External links

| Look up isoform in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |