Gluteus maximus muscle

| Gluteus maximus | |

|---|---|

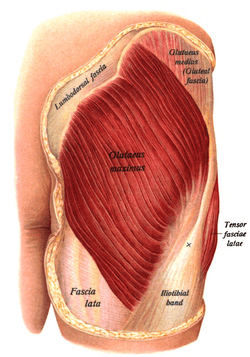

The gluteus maximus, with surrounding fascia. Skin covering area removed. | |

Gluteus maximus is the most superficial muscle of the hips, here visible at top centre with skin removed from the entire leg | |

| Details | |

| Origin | Gluteal surface of ilium, lumbar fascia, sacrum, sacrotuberous ligament |

| Insertion | Gluteal tuberosity of the femur and iliotibial tract |

| Artery | Superior and inferior gluteal arteries |

| Nerve | Inferior gluteal nerve (L5, S1 and S2 nerve roots) |

| Actions | External rotation and extension of the hip joint, supports the extended knee through the iliotibial tract, chief antigravity muscle in sitting and abduction of the hip |

| Antagonist | Iliacus, psoas major and psoas minor |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Musculus glutaeus maximus |

| Dorlands /Elsevier | m_22/12549211 |

| TA | A04.7.02.006 |

| FMA | 22314 |

The gluteus maximus (also known collectively with the gluteus medius and minimus, as the gluteal muscles, and sometimes referred to informally as the "glutes") is the main extensor muscle of the hip. It is the largest and most superficial of the three gluteal muscles and makes up a large portion of the shape and appearance of each side of the hips. Its thick fleshy mass, in a quadrilateral shape, forms the prominence of the buttocks.

Its large size is one of the most characteristic features of the muscular system in humans,[1] connected as it is with the power of maintaining the trunk in the erect posture. Other primates have much flatter hips and can not sustain standing erectly.

The muscle is remarkably coarse in function and structure, being made up of muscle fascicles lying parallel with one another, and collected together into larger bundles separated by fibrous septa.

Structure

It arises from the posterior gluteal line of the inner upper ilium, a pelvic bone, and roughly the portion of the bone including the crest of the ilium (the hip bone), immediately above and behind it; and from the posterior surface of the lower part of the sacrum, the base of the spine, and the side of the coccyx, the tailbone; from the aponeurosis of the erector spinae (lumbodorsal fascia), the sacrotuberous ligament, and the fascia covering the gluteus medius (gluteal aponeurosis). The fibers are directed obliquely downward and lateralward; The gluteus maximus has two insertions:

- those forming the upper and larger portion of the muscle, together with the superficial fibers of the lower portion, end in a thick tendinous lamina, which passes across the greater trochanter, and inserts into the iliotibial band of the fascia lata;

- the deeper fibers of the lower portion of the muscle are inserted into the gluteal tuberosity between the vastus lateralis and adductor magnus.

Bursae

Three bursae are usually found in relation with the deep surface of this muscle:

- One of these, of large size, separates it from the greater trochanter;

- a second, (often missing), is situated on the tuberosity of the ischium;

- a third is found between the tendon of the muscle and that of the vastus lateralis.

Function

When the gluteus maximus takes its fixed point from the pelvis, it extends the acetabulofemoral joint and brings the bent thigh into a line with the body.

Taking its fixed point from below, it acts upon the pelvis, supporting it and the trunk upon the head of the femur; this is particularly obvious in standing on one leg.

Its most powerful action is to cause the body to regain the erect position after stooping, by drawing the pelvis backward, being assisted in this action by the biceps femoris (long head), semitendinosus, semimembranosus, and adductor magnus.

The gluteus maximus is a tensor of the fascia lata, and by its connection with the iliotibial band steadies the femur on the articular surfaces of the tibia during standing, when the extensor muscles are relaxed.

The lower part of the muscle also acts as an adductor and external rotator of the limb. The upper fibers act as abductors of the hip joints.

Society and culture

Training

The gluteus maximus is involved in a number of sports, from running to weight-lifting. A number of exercises focus on the gluteus maximus as well as other muscles of the upper leg.

- Hip thrusts

- Glute bridge

- Quadruped hip extensions

- Kettlebell swings

- Squats (if taken below parallel) and variations like split squats, pistol squats and wide-stance lunges

- Deadlift (and variations)

- Reverse hyperextension

- Four-way hip extensions

- Glute-ham raise

Injury analysis

Functional assessment can be useful in assessing injuries to the gluteus maximus and surrounding muscles. These tests include:

- 30 Second Chair to Stand test

This test measures a participant's ability to stand up from a seated position as many times as possible in a thirty-second period of time.[2] Testing the number of times a person can stand up in a thirty-second period helps assess strength, flexibility, pain, and endurance,[2] which can help determine how far along a person is in rehabilitation, or how much work is still to be done.

- Passive piriformis stretch.

The piriformis test measures flexibility of the gluteus maximus. This requires a trained professional and is based on the angle of external and internal rotation in relation to normal range of motion without injury or impingement.[3]

Evolution

In other primates, gluteus maximus consists of ischiofemoralis, a small muscle that corresponds to the human gluteus maximus and originates from the ilium and the sacroiliac ligament, and gluteus maximus proprius, a large muscle that extends from the ischial tuberosity to a relatively more distant insertion on the femur. In adapting to bipedal gait, reorganization of the attachment of the muscle as well as the moment arm was required.[4]

Additional images

The gluteus maximus as it appear on a skeleton without other muscles

The gluteus maximus as it appear on a skeleton without other muscles All gluteal muscles, maximus in yellow

All gluteal muscles, maximus in yellow Structures surrounding right hip-joint (gluteus maximus visible at bottom)

Structures surrounding right hip-joint (gluteus maximus visible at bottom) Innervation and blood-supply of the gluteus maximus.

Innervation and blood-supply of the gluteus maximus. Gluteus maximus cut showing underlying structures.

Gluteus maximus cut showing underlying structures. Gluteus maximus cut showing underlying structures.

Gluteus maximus cut showing underlying structures. Structures visible under the gluteus maximus.

Structures visible under the gluteus maximus. Innervation as seen from under the gluteus maximus.

Innervation as seen from under the gluteus maximus.- The gluteus medius and nearby muscles.

See also

References

This article incorporates text in the public domain from the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ↑ Norman Eizenberg et al., General Anatomy: Principles and Applications (2008), p 17.

- 1 2 Dobson, F.; Bennell, K.; Hinman, R.; Abbott, H.; Roos, E. "OARSI recommended performance-based tests to assess physical function in people diagnosed with hip or knee osteoarthritis" (PDF).

- ↑ "Passive Piriformis ROM". Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- ↑ Hogervorst T, Vereecke EE (2015). "Evolution of the human hip. Part 2: muscling the double extension". Journal of Hip Preservation Surgery. 2 (1): 3–14. doi:10.1093/jhps/hnu014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gluteus maximus muscles. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Human dissection. |

- Anatomy photo:13:st-0403 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- Cross section image: pelvis/pelvis-female-17—Plastination Laboratory at the Medical University of Vienna

- Cross section image: pelvis/pelvis-e12-15—Plastination Laboratory at the Medical University of Vienna

- Cross section image: pembody/body18b—Plastination Laboratory at the Medical University of Vienna

- Muscles/GluteusMaximus at exrx.net