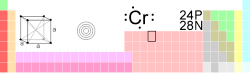

Chromium deficiency

| Chromium deficiency | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chromium | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | endocrinology |

| ICD-10 | E61.4 |

| DiseasesDB | 2625 |

Chromium deficiency is a proposed disorder that results from an insufficient dietary intake of chromium. It is an uncommon, some would say nonexistent,[1] condition.[2][3] Cases of deficiency have been claimed in hospital patients who were fed defined liquid diets intravenously for long periods of time.[4]

Dietary guidelines

The US dietary guidelines for adequate daily chromium intake were lowered in 2001 from 50–200 µg for an adult to 30–35 µg (adult male) and to 20–25 µg (adult female).[5] These amounts were set to be the same as the average amounts consumed by healthy individuals. Consequently, it is thought that few Americans are chromium deficient.[1]

Approximately 2% of ingested chromium(III) is absorbed, with the remainder being excreted in the feces. Amino acids, vitamin C and niacin may enhance the uptake of chromium from the intestinal tract.[6] After absorption, this metal accumulates in the liver, bone, and spleen. Trivalent chromium is found in a wide range of foods, including whole-grain products, processed meats, high-bran breakfast cereals, coffee, nuts, green beans, broccoli, spices, and some brands of wine and beer.[6] Most fruits and vegetables and dairy products contain only low amounts.[4] Most of the chromium in people's diets comes from processing or storing food in pans and cans made of stainless steel, which can contain up to 18% chromium.[4] The amount of chromium in the body can be decreased as a result of a diet high in simple sugars, which increases the excretion of the metal through urine. Because of the high excretion rates and the very low absorption rates of most forms of chromium, acute toxicity is uncommon.

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms of chromium deficiency caused by long-term total parenteral nutrition are severely impaired glucose tolerance, weight loss, and confusion.[7] However, subsequent studies questioned the validity of these findings.[8]

Controversy

Some researchers contend that chromium is not an essential nutrient, that chromium has no beneficial effects on body mass or composition and should be removed from the list of essential trace elements.[9] The proposed mechanism for cellular uptake of CrIII via transferrin has also been called into question.[10]

Supplementation

A natural form of chromium extracted from yeast, Glucose Tolerance Factor (GTF) chromium, was found to exert beneficial insulin-mimetic and insulin-potentiating effects in vitro and in a mouse model the GTF form was seen to produce an insulin-like effect by acting on cellular signals downstream of the insulin receptor. These beneficial results were seen to suggest Glucose Tolerance Factor as a potential source for a novel oral medication for diabetes.[11] However, studies in humans indicate chromium picolinate in particular is described as a "poor choice" as a supplement.[1] A 2007 review concluded that chromium supplements had no beneficial effect on healthy people, but that there might be an improvement in glucose metabolism in diabetics, although the authors stated that the evidence for this effect remains weak.[12]

Although it is controversial whether oral supplements should be taken by healthy adults eating a normal diet,[3] chromium is needed as an ingredient in total parenteral nutrition (TPN), since deficiency can occur after months of intravenous feeding with chromium-free TPN.[7] For this reason, chromium is added to normal TPN solutions.[13]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Vincent, John B. (2010). "Chromium: celebrating 50 years as an essential element?". Dalton Transactions. 39 (16): 3787–3794. PMID 20372701. doi:10.1039/B920480F.

- ↑ Jeejeebhoy, Khursheed N. (1999). "The role of chromium in nutrition and therapeutics and as a potential toxin". Nutrition Reviews. 57 (11): 329–335. PMID 10628183. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.1999.tb06909.x.

- 1 2 Porter, David J.; Raymond, Lawrence W.; Anastasio, Geraldine D. (1999). "Chromium: friend or foe?" (PDF). Archives of Family Medicine. 8 (5): 386–390. PMID 10500510. doi:10.1001/archfami.8.5.386. Archived from the original on 9 January 2005. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- 1 2 3 Expert group on Vitamins and Minerals (August 2002). "Review of Chromium" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ↑ Trumbo, Paula; Yates, Allison A.; Schlicker, Sandra; Poos, Mary (March 2001). "Dietary reference intakes: vitamin A, vitamin K, arsenic, boron, chromium, copper, iodine, iron, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, silicon, vanadium, and zinc". Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 101 (3): 294–301. PMID 11269606. doi:10.1016/S0002-8223(01)00078-5.

- 1 2 Lukaski, Henry C. (1999). "Chromium as a supplement". Annual Review of Nutrition. 19 (1): 279–302. PMID 10448525. doi:10.1146/annurev.nutr.19.1.279.

- 1 2 Freund, Herbert; Atamian, Susan; Fischer, Josef E. (February 1979). "Chromium deficiency during total parenteral nutrition". JAMA. 241 (5): 496–498. PMID 104057. doi:10.1001/jama.1979.03290310036012.

- ↑ John B. Vincent, Kristin R. Di Bona; Sharifa Love; Nicholas R. Rhodes; DeAna McAdory; Sarmistha Halder Sinha; Naomi Kern; Julia Kent; Jessyln Strickland; Austin Wilson; Janis Beaird; James Ramage; Jane F. Rasco (March 2011). "Chromium is not an essential trace element for mammals: effects of a "low-chromium" diet". Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry. 16 (3): 381–390. PMID 21086001. doi:10.1007/s00775-010-0734-y.

- ↑ Vincent, JB (2013). "Chromium: is it essential, pharmacologically relevant, or toxic?". Metal ions in life sciences. 13: 171–98. PMID 24470092. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7500-8_6.

- ↑ Levina, Aviva; Pham, T. H. Nguyen; Lay, Peter A. (1 May 2016). "Binding of Chromium(III) to Transferrin Could be Involved in Detoxification of Dietary Chromium(III) Rather Than Transport of an Essential Trace Element". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 55: 8104–8107. ISSN 1521-3773. PMID 27197571. doi:10.1002/anie.201602996.

- ↑ Weksler-Zangen, Sarah; Mizrahi, Tal; Raz, Itamar; Mirsky, Nitsa (September 2012). "Glucose tolerance factor extracted from yeast: oral insulin-mimetic and insulin-potentiating agent: in vivo and in vitro studies". British Journal of Nutrition. 108 (5): 875–882. PMID 22172158. doi:10.1017/S0007114511006167.

- ↑ Balk, Ethan M.; Tatsioni, Athina; Lichtenstein, Alice H.; Lau, Joseph; Pittas, Anastassios G. (2007). "Effect of chromium supplementation on glucose metabolism and lipids: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials" (PDF). Diabetes Care. 30 (8): 2154–63. PMID 17519436. doi:10.2337/dc06-0996. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ↑ Anderson, R. A. (1995). "Chromium and parenteral nutrition". Nutrition. 11 (1 Suppl): 83–86. PMID 7749258.

Further reading

- Cefalu, William T.; Hu, Frank B. (2004). "Role of Chromium in Human Health and in Diabetes" (PDF). Diabetes Care. 27 (11): 2741–2751. PMID 15505017. doi:10.2337/diacare.27.11.2741. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- Wallach, Stanley (1985). "Clinical and biochemical aspects of chromium deficiency". Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 4 (1): 107–120. PMID 3886757. doi:10.1080/07315724.1985.10720070.

- "Dietary Supplement Fact Sheet: Chromium". Office of Dietary Supplements, National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- Chromium in glucose metabolism