Shoulder joint

| Shoulder joint | |

|---|---|

The right shoulder and shoulder joint | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Articulatio humeri |

| MeSH | A02.835.583.748 |

| Dorlands /Elsevier | a_64/{{{DorlandsSuf}}} |

| TA | A03.5.08.001 |

| FMA | 25912 |

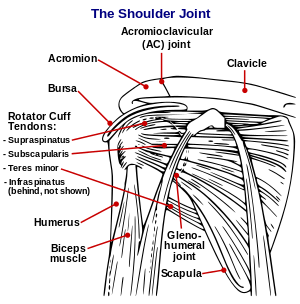

The shoulder joint (or glenohumeral joint from Greek glene, eyeball, + -oid, 'form of', + Latin humerus, shoulder) is structurally classified as a synovial ball and socket joint and functionally as a diarthrosis and multiaxial joint. It involves articulation between the glenoid cavity of the scapula (shoulder blade) and the head of the humerus (upper arm bone).

Due to the very loose joint capsule that gives a limited interface of the humerus and scapula, it is the most mobile joint of the human body.

Structure

The shoulder joint is a ball and socket joint between the scapula and the humerus. However the socket of the glenoid cavity of the scapula is itself quite shallow and is made deeper by the addition of the glenoid labrum. The glenoid labrum is a ring of cartilaginous fibre attached to the circumference of the cavity. This ring is continuous with the tendon of the biceps brachii above. Normal glenohumeral joint space is 4–5 mm.[1]

Between the associated muscles of the shoulder is an anatomic space called the axillary space which transmits the subscapular artery and axillary nerve.

Capsule

The shoulder joint has a very loose joint capsule known as the articular capsule of the humerus and this can sometimes allow the shoulder to dislocate. The long head of the biceps brachii muscle travels inside the capsule from its attachment to the supraglenoid tubercle of the scapula.

Because the tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii is inside the capsule, it requires a tendon sheath to minimize friction.

Bursae

A number of small fluid-filled sacs known as synovial bursae are located around the capsule to aid mobility. Between the joint capsule and the deltoid muscle is the subacromial-subdeltoid bursa. Between the capsule and the acromion is the subacromial bursa. The subcoracoid bursa is between the capsule and the coracoid process of the scapula. The coracobrachial bursa is between the subscapularis muscle and the tendon of the coracobrachialis muscle. Between the capsule and the tendon of the subscapularis muscle is the subscapular bursa, this is also known as the subtendinous bursa of the scapularis. (The supra-acromial bursa does not normally communicate with the shoulder joint).

Muscles

The shoulder joint is a muscle-dependent joint as it lacks strong ligaments. The primary stabilizers of the shoulder include the biceps brachii on the anterior side of the arm, and tendons of the rotator cuff; which are fused to all sides of the capsule except the inferior margin. The tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii passes through the bicipital groove on the humerus and inserts on the superior margin of the glenoid cavity to press the head of the humerus against the glenoid cavity.[2] The tendons of the rotator cuff and their respective muscles (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis) stabilize and fix the joint. The supraspinatus, infraspinatus and teres minor muscles aid in abduction and external rotation of the shoulder, while the subscapularis aids in internal rotation of the humerus.[3]

Ligaments

- Superior, middle and inferior glenohumeral ligaments

- Coracohumeral ligament

- Transverse humeral ligament

- Coraco-acromial ligament[4]

Innervation

The nerves supplying the shoulder joint all arise in the brachial plexus. They are the suprascapular nerve, the axillary nerve and the lateral pectoral nerve.

Blood Supply

The shoulder joint is supplied with blood by branches of the anterior and posterior circumflex humeral arteries, the suprascapular artery and the scapular circumflex artery.

Function

.gif)

The rotator cuff muscles of the shoulder produce a high tensile force, and help to pull the head of the humerus into the glenoid cavity.

The glenoid cavity is shallow and contains the glenoid labrum which deepens it and aids in stability. With 120 degrees of unassisted flexion, the shoulder joint is the most mobile joint in the body.

The movement of the scapula across the rib cage in relation to the humerus is known as the scapulohumeral rhythm, and this helps to achieve a further range of movement. This range can be compromised by anything that changes the position of the scapula. This could be an imbalance in parts of the large trapezius muscles that hold the scapula in place. Such an imbalance could cause a forward head carriage which in turn can affect the range of movements of the shoulder.

Movements

- Flexion and extension of the shoulder joint in the (sagittal plane). Flexion is carried out by the anterior fibres of the deltoid, pectoralis major and the coracobrachialis. Extension is carried out by the latissimus dorsi and posterior fibres of the deltoid.

- Abduction and adduction of the shoulder (frontal plane). Abduction is carried out by the deltoid and the supraspinatus in the first 90 degrees. From 90-180 degrees it is the trapezius and the serratus anterior. Adduction is carried out by the pectoralis major, lattisimus dorsi, teres major and the subscapularis.

- Horizontal abduction and horizontal adduction of the shoulder (transverse plane)

- Medial and lateral rotation of shoulder (also known as internal and external rotation). Medial rotation is carried out by the anterior fibres of the deltoid, teres major, subscapularis, pectoralis major and the lattissimus dorsi. Lateral rotation is carried out by the posterior fibres of the deltoid, infraspinatus and the teres minor.

- Circumduction of the shoulder (a combination of flexion/extension and abduction/adduction).

Clinical significance

The capsule can become inflamed and stiff, with abnormal bands of tissue (adhesions) growing between the joint surfaces, causing pain and restricting movement of the shoulder, a condition known as frozen shoulder or adhesive capsulitis.

A SLAP tear (superior labrum anterior to posterior) is a rupture in the glenoid labrum. SLAP tears are characterized by shoulder pain in specific positions, pain associated with overhead activities such as tennis or overhand throwing sports, and weakness of the shoulder. This type of injury often requires surgical repair.[5]

Anterior dislocation of the glenohumeral joint occurs when the humeral head is displaced in the anterior direction. Anterior shoulder dislocation often is a result of a blow to the shoulder while the arm is in an abducted position. It is not uncommon for the arteries and nerves (axillary nerve) in the axillary region to be damaged as a result of a shoulder dislocation; which if left untreated can result in weakness, muscle atrophy, or paralysis.[6]

Subacromial bursitis is a painful condition caused by inflammation which often presents a set of symptoms known as subacromial impingement.

Additional images

Diagram of the human shoulder joint

Diagram of the human shoulder joint The left shoulder and acromioclavicular joints, and the proper ligaments of the scapula.

The left shoulder and acromioclavicular joints, and the proper ligaments of the scapula.- Dissection image of coracohumeral ligament of glenohumeral joint in green.

- Dissection image of cartilage of glenohumeral joint in green.

See also

References

- ↑ "Glenohumeral joint space". radref.org., in turn citing: Petersson, Claes J.; Redlund-Johnell, Inga (2009). "Joint Space in Normal Gleno-Humeral Radiographs". Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica. 54 (2): 274–276. ISSN 0001-6470. doi:10.3109/17453678308996569.

- ↑ Saladin, Kenneth S. (2012). Anatomy & Physiology: The Unity of Form and Function (Sixth ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ Hub, Ken. The Rotator Cuff. 2014. 10 December 2014

- ↑ Moore, K.; Dalley, A.; Agur, A. (2014). Moore Clinically Oriented Anatomy, (7th ed.). Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

- ↑ "Shoulder Pain: Raising the level of diagnostic certainty about SLAP lesions". Clinical Updates for Medical Professionals. Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ↑ Saladin, Kenneth (2015). Anatomy & Physiology: The Unity of Form and Function (Seventh ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. p. 296.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shoulder joint. |

- Overview at brown.edu

- Overview at ouhsc.edu

- Anatomy figure: 10:03-12 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- Diagram at yess.uk.com