Glacier National Park (U.S.)

| Glacier National Park | |

|---|---|

|

IUCN category II (national park) | |

|

Mountain goat, official symbol of Glacier NP | |

Glacier | |

| Location | Flathead County & Glacier County, Montana, United States |

| Nearest city | Columbia Falls, Montana |

| Coordinates | 48°41′48″N 113°43′6″W / 48.69667°N 113.71833°WCoordinates: 48°41′48″N 113°43′6″W / 48.69667°N 113.71833°W |

| Area | 1,013,322 acres (4,100.77 km2)[1] |

| Established | May 11, 1910 |

| Visitors | 2,946,681 (in 2016)[2] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Glacier National Park |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| Criteria |

Natural: (vii), (ix) |

| Reference | 354 |

| Inscription | 1995 (19th Session) |

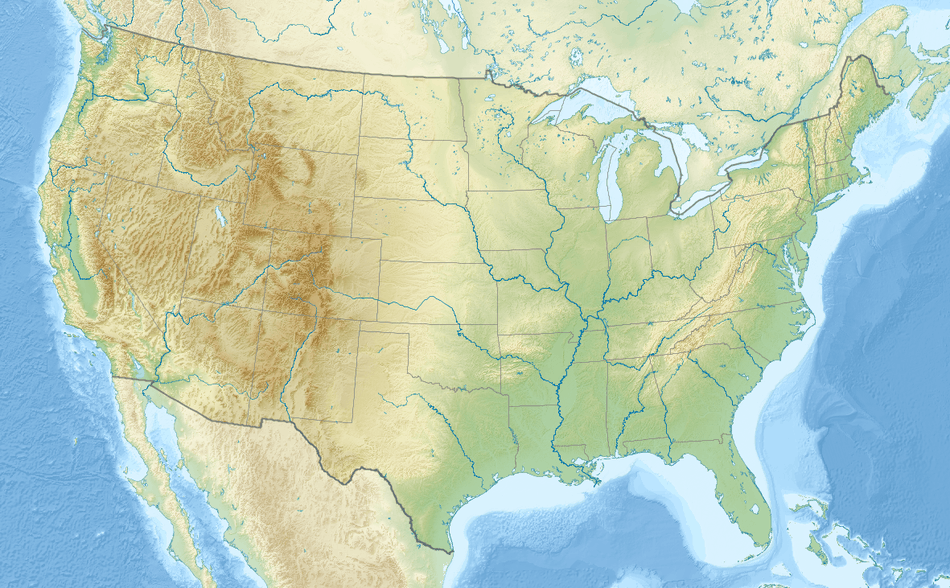

Glacier National Park is a national park located in the U.S. state of Montana, on the Canada–United States border with the Canadian provinces of Alberta and British Columbia. The park encompasses over 1 million acres (4,000 km2) and includes parts of two mountain ranges (sub-ranges of the Rocky Mountains), over 130 named lakes, more than 1,000 different species of plants, and hundreds of species of animals. This vast pristine ecosystem is the centerpiece of what has been referred to as the "Crown of the Continent Ecosystem", a region of protected land encompassing 16,000 square miles (41,000 km2).[3]

The region that became Glacier National Park was first inhabited by Native Americans. Upon the arrival of European explorers, it was dominated by the Blackfeet in the east and the Flathead in the western regions. Under pressure, the Blackfeet ceded the mountainous parts of their treaty lands in 1895 to the federal government; it later became part of the park. Soon after the establishment of the park on May 11, 1910, a number of hotels and chalets were constructed by the Great Northern Railway. These historic hotels and chalets are listed as National Historic Landmarks and a total of 350 locations are on the National Register of Historic Places. By 1932 work was completed on the Going-to-the-Sun Road, later designated a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark, which provided greater accessibility for automobiles into the heart of the park.

The mountains of Glacier National Park began forming 170 million years ago when ancient rocks were forced eastward up and over much younger rock strata. Known as the Lewis Overthrust, these sedimentary rocks are considered to have some of the finest examples of early life fossils on Earth. The current shapes of the Lewis and Livingston mountain ranges and positioning and size of the lakes show the telltale evidence of massive glacial action, which carved U-shaped valleys and left behind moraines which impounded water, creating lakes. Of the estimated 150 glaciers which existed in the park in the mid-19th century, only 25 active glaciers remained by 2010.[4] Scientists studying the glaciers in the park have estimated that all the glaciers may disappear by 2030 if current climate patterns persist.[5]

Glacier National Park has almost all its original native plant and animal species. Large mammals such as Grizzly bears, moose, and mountain goats, as well as rare or endangered species like wolverines and Canadian lynxes, inhabit the park. Hundreds of species of birds, more than a dozen fish species, and a few reptile and amphibian species have been documented. The park has numerous ecosystems ranging from prairie to tundra. Notably, the easternmost forests of western redcedar and hemlock grow in the southwest portion of the park. Large forest fires are uncommon in the park. However, in 2003 over 13% of the park burned.[6]

Glacier National Park borders Waterton Lakes National Park in Canada—the two parks are known as the Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park and were designated as the world's first International Peace Park in 1932. Both parks were designated by the United Nations as Biosphere Reserves in 1976, and in 1995 as World Heritage sites.[7][8] In April 2017, the joint Park received a fourth designation with "provisional Gold Tier designation as Waterton-Glacier International Dark Sky Park through the International Dark Sky Association"[9], the first transboundary dark sky park.

History

According to archeological evidence, Native Americans first arrived in the Glacier area some 10,000 years ago. The earliest occupants with lineage to current tribes were the Flathead (Salish) and Kootenai,[11] Shoshone, and Cheyenne. The Blackfeet arrived around the beginning of the 18th century and soon dominated the eastern slopes of what later became the park, as well as the Great Plains immediately to the east.[8] The park region provided the Blackfeet shelter from the harsh winter winds of the plains, allowing them to supplement their traditional bison hunts with other game meat. Today, the Blackfeet Indian Reservation borders the park in the east, while the Flathead Indian Reservation is located west and south of the park. When the Blackfeet Reservation was first established in 1855 by the Lame Bull Treaty, it included the eastern area of the current park up to the Continental Divide.[12] To the Blackfeet, the mountains of this area, especially Chief Mountain and the region in the southeast at Two Medicine, were considered the "Backbone of the World" and were frequented during vision quests.[13] In 1895 Chief White Calf of the Blackfeet authorized the sale of the mountain area, some 800,000 acres (3,200 km2), to the U.S. government for $1.5 million, with the understanding that they would maintain usage rights to the land for hunting as long as the ceded stripe will be public land of the United States.[14] This established the current boundary between the park and the reservation.

—George Bird Grinnell (1901)[15]

While exploring the Marias River in 1806, the Lewis and Clark Expedition came within 50 miles (80 km) of the area that is now the park.[8] A series of explorations after 1850 helped to shape the understanding of the area that later became the park. In 1885 George Bird Grinnell hired noted explorer (and later well regarded author) James Willard Schultz to guide him on a hunting expedition into what would later become the park.[16] After several more trips to the region, Grinnell became so inspired by the scenery that he spent the next two decades working to establish a national park. In 1901 Grinnell wrote a description of the region in which he referred to it as the "Crown of the Continent". His efforts to protect the land make him the premier contributor to this cause.[17] A few years after Grinnell first visited, Henry L. Stimson and two companions, including a Blackfoot, climbed the steep east face of Chief Mountain in 1892.

In 1891 the Great Northern Railway crossed the Continental Divide at Marias Pass 5,213 feet (1,589 m), which is along the southern boundary of the park. In an effort to stimulate use of the railroad, the Great Northern soon advertised the splendors of the region to the public. The company lobbied the United States Congress. In 1897 the park was designated as a forest preserve.[18] Under the forest designation, mining was still allowed but was not commercially successful. Meanwhile, proponents of protecting the region kept up their efforts. In 1910, under the influence of the Boone and Crockett Club,[19] spearheaded by Club members George Bird Grinnell, Henry L. Stimson, and the railroad, a bill was introduced into the U.S. Congress which redesignated the region from a forest reserve to a national park. This bill was signed into law by President William Howard Taft on May 11, 1910.[20][21] In 1910 George Bird Grinnell wrote, "This Park, the country owes to the Boone and Crockett Club, whose members discovered the region, suggested it being set aside, caused the bill to be introduced into congress and awakened interest in it all over the country".[22]

From May until August 1910, the forest reserve supervisor, Fremont Nathan Haines, managed the park's resources as the first acting superintendent. In August 1910, William Logan was appointed the park's first superintendent. While the designation of the forest reserve confirmed the traditional usage rights of the Blackfeet, the enabling legislation of the national park does not mention the guarantees to the Native Americans. It is the position of the United States government that with the special designation as a National Park the mountains ceded their multi-purpose public land status and the former rights ceased to exist as it was confirmed by the Court of Claims in 1935. Some Blackfeet held that their traditional usage rights still exist de jure. In the 1890s, armed standoffs were avoided narrowly several times.[23]

The Great Northern Railway, under the supervision of president Louis W. Hill, built a number of hotels and chalets throughout the park in the 1910s to promote tourism. These buildings, constructed and operated by a Great Northern subsidiary called the Glacier Park Company, were modeled on Swiss architecture as part of Hill's plan to portray Glacier as "America's Switzerland". Hill was especially interested in sponsoring artists to come to the park, building tourist lodges that displayed their work. His hotels in the park never made a profit but they attracted thousands of visitors who came via the Great Northern.[24]

Vacationers commonly took pack trips on horseback between the lodges or utilized the seasonal stagecoach routes to gain access to the Many Glacier area in the northeast.[25]

The chalets, built between 1910 and 1913, included Belton, St. Mary, Going-to-the-Sun, Many Glacier, Two Medicine, Sperry, Granite Park, Cut Bank, and Gunsight Lake. The railway also built Glacier Park Lodge, adjacent to the park on its east side, and the Many Glacier Hotel on the east shore of Swiftcurrent Lake. Louis Hill personally selected the sites for all of these buildings, choosing each for their dramatic scenic backdrops and views. Another developer, John Lewis, built the Lewis Glacier Hotel on Lake McDonald in 1913–1914. The Great Northern Railway bought the hotel in 1930 and it was later renamed Lake McDonald Lodge.[26] Some of the chalets were in remote backcountry locations accessible only by trail. Today, only Sperry, Granite Park, and Belton Chalets are still in operation, while a building formerly belonging to Two Medicine Chalet is now Two Medicine Store.[27] The surviving chalet and hotel buildings within the park are now designated as National Historic Landmarks.[28] In total, 350 buildings and structures within the park are listed on the National Register of Historic Places, including ranger stations, backcountry patrol cabins, fire lookouts, and concession facilities.[29]

After the park was well established and visitors began to rely more on automobiles, work was begun on the 53-mile (85 km) long Going-to-the-Sun Road, completed in 1932. Also known simply as the Sun Road, the road bisects the park and is the only route that ventures deep into the park, going over the Continental Divide at Logan Pass, 6,646 feet (2,026 m) at the midway point. The Sun Road is also listed on the National Register of Historic Places and in 1985 was designated a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark.[30] Another route, along the southern boundary between the park and National Forests, is U.S. Route 2, which crosses the Continental Divide at Marias Pass and connects the towns of West Glacier and East Glacier.

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), a New Deal relief agency for young men, played a major role between 1933 and 1942 in developing both Glacier National Park and Yellowstone National Park. CCC projects included reforestation, campground development, trail construction, fire hazard reduction, and fire-fighting work.[31] The increase in motor vehicle traffic through the park during the 1930s resulted in the construction of new concession facilities at Swiftcurrent and Rising Sun, both designed for automobile-based tourism. These early auto camps are now also listed on the National Register.[27]

In 2011, Glacier National Park was depicted on the seventh quarter in the America the Beautiful Quarters series.[32]

Park management

Glacier National Park is managed by the National Park Service, with the park's headquarters in West Glacier, Montana. Visitation to Glacier National Park averaged about 2.2 million visitors annually over the ten-year period from 2007 to 2016,[2] though relatively few of those visitors ventured far from the roadways, hotels and campgrounds.

Glacier National Park finished with a budget of $13,803,000 in 2016, with a planned budget of $13,777,000 for 2017.[33] In anticipation of the 100th anniversary of the park in 2010, major reconstruction of the Going-to-the-Sun Road was completed, creating temporary road closures. The Federal Highway Administration managed the reconstruction project in cooperation with the National Park Service.[34] Some rehabilitation of major structures such as visitor centers and historic hotels, as well as improvements in wastewater treatment facilities and campgrounds, are expected to be completed by the anniversary date. Also planned are fishery studies for Lake McDonald, updates of the historical archives, and restoration of trails.

The mandate of the National Park Service is to "... preserve and protect natural and cultural resources". The Organic Act of August 25, 1916 established the National Park Service as a federal agency. One major section of the Act has often been summarized as the "Mission", "... to promote and regulate the use of the ... national parks ... which purpose is to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations."[35] In keeping with this mandate, hunting is illegal in the park, as are mining, logging, and the removal of natural or cultural resources. Additionally, oil and gas exploration and extraction are not permitted. These restrictions, however, caused a lot of conflict with the adjoining Blackfeet Indian Reservation. When they sold the land to the United States government, it was with the stipulation of being able to maintain their usage rights of the area, many of which (such as hunting) had come into conflict with these regulations.[14]

In 1974, a wilderness study was submitted to Congress which identified 95% of the area of the park as qualifying for wilderness designation. Unlike a few other parks, Glacier National Park has yet to be protected as wilderness, but National Park Service policy requires that identified areas listed in the report be managed as wilderness until Congress renders a full decision.[29] Ninety-three percent of Glacier National Park is managed as wilderness, even though it has not been officially designated.[36]

Geography and geology

The park is bordered on the north by Waterton Lakes National Park in Alberta, and the Flathead Provincial Forest and Akamina-Kishinena Provincial Park in British Columbia.[37] To the west, the north fork of the Flathead River forms the western boundary, while its middle fork is part of the southern boundary. The Blackfeet Indian Reservation provides most of the eastern boundary. The Lewis and Clark and the Flathead National Forests form the southern and western boundary.[38] The remote Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex is located in the two forests immediately to the south.[39]

The park contains a dozen large lakes and 700 smaller ones, but only 131 lakes have been named.[40] Lake McDonald on the western side of the park is the longest at 9.4 miles (15.1 km), the largest in area at 6,823 acres (27.61 km2), and the deepest at 464 feet (141 m). Numerous smaller lakes, known as tarns, are located in cirques formed by glacial erosion. Some of these lakes, like Avalanche Lake and Cracker Lake, are colored an opaque turquoise by suspended glacial silt, which also causes a number of streams to run milky white. The lakes of Glacier National Park remain cold year round, with temperatures rarely above 50 °F (10 °C) at their surface.[40] Cold water lakes such as these support little plankton growth, ensuring that the lake waters are remarkably clear. The lack of plankton, however, lowers the rate of pollution filtration, so pollutants have a tendency to linger longer. Consequently, the lakes are considered environmental bellwethers as they can be quickly affected by even minor increases in pollutants.[41]

Two hundred waterfalls are scattered throughout the park. However, during drier times of the year, many of these are reduced to a trickle. The largest falls include those in the Two Medicine region, McDonald Falls in the McDonald Valley, and Swiftcurrent Falls in the Many Glacier area, which is easily observable and close to the Many Glacier Hotel. One of the tallest waterfalls is Bird Woman Falls, which drops 492 feet (150 m) from a hanging valley beneath the north slope of Mount Oberlin.[42]

Geology

The rocks found in the park are primarily sedimentary rocks of the Belt Supergroup. They were deposited in shallow seas over 1.6 billion to 800 million years ago. During the formation of the Rocky Mountains 170 million years ago, one region of rocks now known as the Lewis Overthrust was forced eastward 50 miles (80 km). This overthrust was several miles (kilometers) thick and hundreds of miles (kilometers) long.[43] This resulted in older rocks being displaced over newer ones, so the overlying Proterozoic rocks are between 1.4 and 1.5 billion years older than Cretaceous age rocks they now rest on.[43][44]

One of the most dramatic evidences of this overthrust is visible in the form of Chief Mountain, an isolated peak on the edge of the eastern boundary of the park rising 2,500 feet (800 m) above the Great Plains.[44][45] There are six mountains in the park over 10,000 feet (3,000 m) in elevation, with Mount Cleveland at 10,466 feet (3,190 m) being the tallest.[46] Appropriately named Triple Divide Peak sends waters towards the Pacific Ocean, Hudson Bay, and Gulf of Mexico watersheds. This peak can effectively be considered to be the apex of the North American continent, although the mountain is only 8,020 feet (2,444 m) above sea level.[47]

The rocks in Glacier National Park are the best preserved Proterozoic sedimentary rocks in the world, with some of the world's most fruitful sources for records of early life. Sedimentary rocks of similar age located in other regions have been greatly altered by mountain building and other metamorphic changes; consequently fossils are less common and more difficult to observe.[48] The rocks in the park preserve such features as millimeter-scale lamination, ripple marks, mud cracks, salt-crystal casts, raindrop impressions, oolites, and other sedimentary bedding characteristics. Six fossilized species of Stromatolites, early organisms consisting of primarily blue-green algae, have been documented and dated at about 1 billion years.[45] The discovery of the Appekunny Formation, a well preserved rock stratum in the park, pushed back the established date for the origination of animal life a full billion years. This rock formation has bedding structures which are believed to be the remains of the earliest identified metazoan (animal) life on Earth.[44]

Glaciers

Glacier National Park is dominated by mountains which were carved into their present shapes by the huge glaciers of the last ice age. These glaciers have largely disappeared over the last 12,000 years.[49] Evidence of widespread glacial action is found throughout the park in the form of U-shaped valleys, cirques, arêtes, and large outflow lakes radiating like fingers from the base of the highest peaks.[5] Since the end of the ice ages, various warming and cooling trends have occurred. The last recent cooling trend was during the Little Ice Age, which took place approximately between 1550 and 1850.[50] During the Little Ice Age, the glaciers in the park expanded and advanced, although to nowhere near as great an extent as they had during the Ice Age.[49]

During the middle of the 20th century, examination of the maps and photographs from the previous century provided clear evidence that the 150 glaciers known to have existed in the park a hundred years earlier had greatly retreated, and in many cases disappeared altogether.[51] Repeat photography of the glaciers, such as the pictures taken of Grinnell Glacier between 1938 and 2009 as shown, help to provide visual confirmation of the extent of glacier retreat.

|

In the 1980s, the U.S. Geological Survey began a more systematic study of the remaining glaciers, which has continued to the present day. By 2010, 37 glaciers remained, but only 25 of these were considered to be "active glaciers" of at least 25 acres (0.10 km2) in area.[4][51] The National Park Service warns that if the current warming trend continues, the park's remaining glaciers will be gone by 2030.[5] This glacier retreat follows a worldwide pattern that has accelerated even more since 1980. Without a major climatic change in which cooler and moister weather returns and persists, the mass balance, which is the accumulation rate versus the ablation (melting) rate of glaciers, will continue to be negative and the glaciers have been projected to eventually disappear, leaving behind only barren rock.[52]

After the end of the Little Ice Age in 1850, the glaciers in the park retreated moderately until the 1910s. Between 1917 and 1941, the retreat rate accelerated and was as high as 330 feet (100 m) per year for some glaciers.[51] A slight cooling trend from the 1940s until 1979 helped to slow the rate of retreat and, in a few cases, even advanced the glaciers over ten meters. However, during the 1980s, the glaciers in the park began a steady period of loss of glacial ice, which continues as of 2010. In 1850, the glaciers in the region near Blackfoot and Jackson Glaciers covered 5,337 acres (21.6 km2), but by 1979, the same region of the park had glacier ice covering only 1,828 acres (7.4 km2). Between 1850 and 1979, 73% of the glacial ice had melted away.[53] At the time the park was created, Jackson Glacier was part of Blackfoot Glacier, but the two have separated into individual glaciers since.[54]

The impact of glacier retreat on the park's ecosystems is not fully known, but plant and animal species that are dependent on cold water could suffer due to a loss of habitat. Reduced seasonal melting of glacial ice may also affect stream flow during the dry summer and fall seasons, reducing water table levels and increasing the risk of forest fires. The loss of glaciers will also reduce the aesthetic visual appeal that glaciers provide to visitors.[53]

Climate

As the park spans the Continental Divide, and has more than 7,000 feet (2,100 m) in elevation variance, many climates and microclimates are found in the park. As with other alpine systems, average temperature usually drops as elevation increases.[55] The western side of the park, in the Pacific watershed, has a milder and wetter climate, due to its lower elevation. Precipitation is greatest during the winter and spring, averaging 2 to 3 inches (50 to 80 mm) per month. Snowfall can occur at any time of the year, even in the summer, and especially at higher altitudes. The winter can bring prolonged cold waves, especially on the eastern side of the Continental Divide, which has a higher elevation overall.[56] Snowfalls are significant over the course of the winter, with the largest accumulation occurring in the west. During the tourist season, daytime high temperatures average 60 to 70 °F (16 to 21 °C), and nighttime lows usually drop into the 40 °F (4 °C) range. Temperatures in the high country may be much cooler. In the lower western valleys, daytime highs in the summer may reach 90 °F (30 °C).[57]

Rapid temperature changes have been noted in the region. In Browning, Montana, just east of the park in the Blackfeet Reservation, a world record temperature drop of 100 °F (56 °C) in only 24 hours occurred on the night of January 23–24, 1916, when thermometers plunged from 44 to −56 °F (7 to −49 °C).[58]

Glacier National Park has a highly regarded global climate change research program. Based in West Glacier, with the main headquarters in Bozeman, Montana, the U.S. Geological Survey has performed scientific research on specific climate change studies since 1992. In addition to the study of the retreating glaciers, research performed includes forest modeling studies in which fire ecology and habitat alterations are analyzed. Additionally, changes in alpine vegetation patterns are documented, watershed studies in which stream flow rates and temperatures are recorded frequently at fixed gauging stations, and atmospheric research in which UV-B radiation, ozone and other atmospheric gases are analyzed over time. The research compiled contributes to a broader understanding of climate changes in the park. The data collected, when compared to other facilities scattered around the world, help to correlate these climatic changes on a global scale.[59][60]

Glacier is considered to have excellent air and water quality. No major areas of dense human population exist anywhere near the region and industrial effects are minimized due to a scarcity of factories and other potential contributors of pollutants.[61] However, the sterile and cold lakes found throughout the park are easily contaminated by airborne pollutants that fall whenever it rains or snows, and some evidence of these pollutants has been found in park waters. Wildfires could also impact the quality of water. However, the pollution level is currently viewed as negligible, and the park lakes and waterways have a water quality rating of A-1, the highest rating given by the state of Montana.[62]

| Climate data for Glacier National Park, elev. 3,154 feet (961 m) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 55 (13) |

58 (14) |

66 (19) |

83 (28) |

90 (32) |

93 (34) |

99 (37) |

99 (37) |

95 (35) |

79 (26) |

65 (18) |

52 (11) |

99 (37) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 30.5 (−0.8) |

35.0 (1.7) |

43.2 (6.2) |

54.0 (12.2) |

64.5 (18.1) |

71.7 (22.1) |

80.0 (26.7) |

79.3 (26.3) |

67.5 (19.7) |

52.3 (11.3) |

37.3 (2.9) |

28.8 (−1.8) |

53.8 (12.1) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 18.3 (−7.6) |

18.9 (−7.3) |

24.6 (−4.1) |

30.6 (−0.8) |

38.0 (3.3) |

44.3 (6.8) |

48.5 (9.2) |

47.1 (8.4) |

39.3 (4.1) |

32.0 (0) |

25.5 (−3.6) |

17.8 (−7.9) |

32.1 (0.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −35 (−37) |

−32 (−36) |

−30 (−34) |

3 (−16) |

13 (−11) |

24 (−4) |

31 (−1) |

26 (−3) |

18 (−8) |

−3 (−19) |

−29 (−34) |

−36 (−38) |

−36 (−38) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.23 (82) |

1.98 (50.3) |

2.08 (52.8) |

1.93 (49) |

2.64 (67.1) |

3.47 (88.1) |

1.70 (43.2) |

1.30 (33) |

2.05 (52.1) |

2.49 (63.2) |

3.27 (83.1) |

3.01 (76.5) |

29.15 (740.4) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 29.5 (74.9) |

16.8 (42.7) |

13.6 (34.5) |

2.9 (7.4) |

0.3 (0.8) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

1.7 (4.3) |

17.9 (45.5) |

34.3 (87.1) |

117 (297.2) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 16.5 | 12.9 | 13.5 | 12.1 | 14.0 | 14.7 | 9.5 | 7.8 | 9.4 | 12.4 | 16.2 | 16.5 | 155.5 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 12.6 | 8.3 | 5.8 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 6.9 | 13.4 | 49.9 |

| Source #1: NOAA (normals, 1981–2010)[63] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Western Regional Climate Center (extremes 1949–present)[64] | |||||||||||||

Wildlife and ecology

Flora

Glacier is part of a large preserved ecosystem collectively known as the "Crown of the Continent Ecosystem", all of which is primarily untouched wilderness of a pristine quality. Virtually all the plants and animals which existed at the time European explorers first entered the region are present in the park today.[65]

A total of over 1,132 plant species have been identified parkwide.[66] The predominantly coniferous forest is home to various species of trees such as the Engelmann spruce, Douglas fir, subalpine fir, limber pine and western larch, which is a deciduous conifer, producing cones but losing its needles each fall. Cottonwood and aspen are the more common deciduous trees and are found at lower elevations, usually along lakes and streams.[55] The timberline on the eastern side of the park is almost 800 feet (244 m) lower than on the western side of the Continental Divide, due to exposure to the colder winds and weather of the Great Plains. West of the Continental Divide, the forest receives more moisture and is more protected from the winter, resulting in a more densely populated forest with taller trees. Above the forested valleys and mountain slopes, alpine tundra conditions prevail, with grasses and small plants eking out an existence in a region that enjoys as little as three months without snow cover.[67] Thirty species of plants are found only in the park and surrounding national forests.[66] Beargrass, a tall flowering plant, is commonly found near moisture sources, and is relatively widespread during July and August. Wildflowers such as monkeyflower, glacier lily, fireweed, balsamroot and Indian paintbrush are also common.

The forested sections fall into three major climatic zones. The west and northwest are dominated by spruce and fir and the southwest by redcedar and hemlock; the areas east of the Continental Divide are a combination of mixed pine, spruce, fir and prairie zones. The cedar-hemlock groves along the Lake McDonald valley are the easternmost examples of this Pacific climatic ecosystem.[68]

Whitebark pine communities have been heavily damaged due to the effects of blister rust, a non native fungus. In Glacier and the surrounding region, 30% of the whitebark pine trees have died and over 70% of the remaining trees are currently infected. The whitebark pine provides a high fat pine cone seed, commonly known as the pine nut, that is a favorite food of red squirrels and Clark's nutcracker. Both grizzlies and black bears are known to raid squirrel caches of pine nuts, one of the bears' favorite foods. Between 1930 and 1970, efforts to control the spread of blister rust were unsuccessful, and continued destruction of whitebark pines appears likely, with attendant negative impacts on dependent species.[69]

Fauna

_8625.jpg)

Virtually all the historically known plant and animal species, with the exception of the bison and woodland caribou, are still present, providing biologists with an intact ecosystem for plant and animal research. Two threatened species of mammals, the grizzly bear and the Canadian lynx, are found in the park.[36] Although their numbers remain at historical levels, both are listed as threatened because in nearly every other region of the U.S. outside of Alaska, they are either extremely rare or absent from their historical range. On average, one or two bear attacks on humans occur each year; since the creation of the park in 1910, there have been a total of 10 bear-related deaths.[70] The number of grizzlies and lynx in the park is not known for certain, but park biologists believed as of 2008 that there were just above 300 grizzlies in the park; a study which commenced in 2001 hopes to determine the number of lynx.[36][71] The exact population figures for grizzlies and the smaller black bear are not known but biologists are using a variety of methods to try to determine an accurate population range.[72] Another study has indicated that the wolverine, another very rare mammal in the lower 48 states, also lives in the park.[73] Other mammals such as the mountain goat (the official park symbol), bighorn sheep, moose, elk, mule deer, skunk, white-tailed deer, bobcat, coyote, and cougar are either plentiful or common.[74] Unlike in Yellowstone National Park, which implemented a wolf reintroduction program in the 1990s, it is believed that wolves recolonized Glacier National Park naturally during the 1980s.[75] Sixty-two species of mammals have been documented including badger, river otter, porcupine, mink, marten, fisher, six species of bat and numerous other smaller mammals.[74]

A total of 260 species of birds have been recorded, with raptors such as the bald eagle, golden eagle, peregrine falcon, osprey and several species of hawks residing year round.[76] The harlequin duck is a colorful species of waterfowl found in the lakes and waterways. The great blue heron, tundra swan, Canada goose and American wigeon are species of waterfowl more commonly encountered in the park. Great horned owl, Clark's nutcracker, Steller's jay, pileated woodpecker and cedar waxwing reside in the dense forests along the mountainsides, and in the higher altitudes, the ptarmigan, timberline sparrow and rosy finch are the most likely to be seen.[76][77] The Clark's nutcracker is less plentiful than in past years due to the decline in the number of whitebark pines.[69]

Because of the colder climate, ectothermic reptiles are all but absent, with two species of garter snake and the western painted turtle being the only three reptile species proven to exist.[78] Similarly, only six species of amphibians are documented, although those species exist in large numbers. After a forest fire in 2001, a few park roads were temporarily closed the following year to allow thousands of western toads to migrate to other areas.[79]

A total of 23 species of fish reside in park waters and native game fish species found in the lakes and streams include the westslope cutthroat trout, northern pike, mountain whitefish, kokanee salmon and Arctic grayling. Glacier is also home to the threatened bull trout, which is illegal to possess and must be returned to the water if caught inadvertently.[80] Introduction in previous decades of lake trout and other non-native fish species has greatly impacted some native fish populations, especially the bull trout and west slope cutthroat trout.[81]

Fire ecology

Forest fires were viewed for many decades as a threat to protected areas such as forests and parks. As a better understanding of fire ecology developed after the 1960s, forest fires were understood to be a natural part of the ecosystem. The earlier policies of suppression resulted in the accumulation of dead and decaying trees and plants, which would normally have been reduced had fires been allowed to burn. Many species of plants and animals actually need wildfires to help replenish the soil with nutrients and to open up areas that allow grasses and smaller plants to thrive.[82] Glacier National Park has a fire management plan which ensures that human-caused fires are generally suppressed. In the case of natural fires, the fire is monitored and suppression is dependent on the size and threat the fire may pose to human safety and structures.[83]

Increased population and the growth of suburban areas near parklands, has led to the development of what is known as Wildland Urban Interface Fire Management, in which the park cooperates with adjacent property owners in improving safety and fire awareness. This approach is common to many other protected areas. As part of this program, houses and structures near the park are designed to be more fire resistant. Dead and fallen trees are removed from near places of human habitation, reducing the available fuel load and the risk of a catastrophic fire, and advance warning systems are developed to help alert property owners and visitors about forest fire potentials during a given period of the year.[84] Glacier National Park has an average of 14 fires with 5,000 acres (20 km2) burnt each year.[85] In 2003, 136,000 acres (550 km2) burned in the park after a five-year drought and a summer season of almost no precipitation. This was the most area transformed by fire since the creation of the park in 1910.[6]

Recreation

Glacier is distant from major cities. The closest airport is in Kalispell, Montana, southwest of the park. Amtrak trains stop at East and West Glacier, and Essex. A fleet of restored 1930s White Motor Company coaches, called Red Jammers, offer tours on all the main roads in the park. The drivers of the buses are called "Jammers", due to the gear-jamming that formerly occurred during the vehicles' operation. The tour buses were rebuilt in 2001 by Ford Motor Company. The bodies were removed from their original chassis and built on modern Ford E-Series van chassis.[86] They were also converted to run on propane to lessen their environmental impact.[87]

Historic wooden tour boats, some dating back to the 1920s, operate on some of the larger lakes. Several of these boats have been in continuous seasonal operation at Glacier National Park since 1927 and carry up to 80 passengers.[88]

Hiking is popular in the park. Over half of the visitors to the park report taking a hike on the park's nearly 700 miles (1,127 km) of trails.[89] 110 miles (177 km) of the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail spans most of the distance of the park north to south, with a few alternative routes at lower elevations if high altitude passes are closed due to snow. The Pacific Northwest National Scenic Trail crosses the park on 52 miles (84 km) from east to west.

Dogs are not permitted on any trails in the park due to the presence of bears and other large mammals. Dogs are permitted at front country campsites that can be accessed by a vehicle and along paved roads.

Anyone entering the United States over land or waterway from Canada must have a passport with them.[90]

Many day hikes can be taken in the park. Back-country camping is allowed at campsites along the trails. A permit is required and can be obtained from certain visitor centers or arranged for in advance. Much of Glacier's back country is usually inaccessible to hikers until early June due to accumulated snow pack and avalanche risk, and many trails at higher altitudes remain snow packed until July.[91] Campgrounds that allow vehicle access are found throughout the park, most of which are near one of the larger lakes. The campgrounds at St. Mary and at Apgar are open year-round, but conditions are primitive in the off-season, as the restroom facilities are closed and there is no running water. All campgrounds with vehicle access are usually open from mid-June until mid-September.[92] Guide and shuttle services are also available.

Fishing is popular in the park. Some of the finest fly fishing in North America can be found in the streams that flow through Glacier National Park. Though the park requires that those fishing understand the regulations, no permit is required to fish the waters within the park boundary. The threatened bull trout must be released immediately back to the water if caught; otherwise, the regulations on limits of catch per day are liberal.[93]

Winter recreation in Glacier is limited. Snowmobiling is illegal throughout the park. Cross-country skiing is permitted in the lower altitude valleys away from avalanche zones.[94]

Gallery

_8633.jpg) Hidden Lake and Bearhat Mountain (right)

Hidden Lake and Bearhat Mountain (right)

Saint Mary Lake and Wild Goose Island

Saint Mary Lake and Wild Goose Island Visitors observing Mountain Goats

Visitors observing Mountain Goats

In popular culture

- Glacier Park Remembered, a documentary produced by Montana PBS[95]

- Through Glacier Park in 1915 / Seeing America first with Howard Eaton (With Illustrations), a road trip travelogue by Mary Roberts Rinehart[96]

- Tenting Tonight: A Chronicle of Sport and Adventure in Glacier Park and Cascade Mountains (1918) by Mary Roberts Rinehart, first published in Cosmopolitan (1917)[97]

See also

- Glacier National Park (Canada)

- List of national parks of the United States

- T. J. Hileman, photographer

References

- ↑ "Listing of acreage as of December 31, 2011". Land Resource Division, National Park Service. Retrieved 2012-03-06.

- 1 2 "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service. Retrieved 2017-02-08.

- ↑ "Welcome to the Crown of the Continent Ecosystem". Crown of the Continent Ecosystem Education Consortium. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- 1 2 Brown, Matthew (2010-04-07). "Glacier National Park loses two glaciers". Huffington Post. Retrieved 2011-05-09.

- 1 2 3 "Glaciers / Glacial Features". National Park Service. 2009-09-22. Retrieved 2010-04-24.

- 1 2 "Fire Regime". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. 2008-03-29. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- ↑ "Biosphere Reserve Information". United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization. 2005-03-11. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- 1 2 3 "Historical Overview,". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- ↑ Staff. "2017 - Summer Guide to Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park" (PDF). nps.gov. National Park Service. p. 1. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ↑ Schultz, James Willard (1916). Blackfeet Tales of Glacier National Park. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin & Co.

- ↑ "History". National Park Service. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ↑ "The Blackfeet Nation". Manataka American Indian Council. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- ↑ Grinnell, George Bird (1892). Blackfoot Lodge Tales (PDF). New York: Charles Scribners Sons. ISBN 0-665-06625-2. Retrieved 2010-04-24.

- 1 2 Spence, Mark David (1999). Dispossessing the Wilderness. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-19-514243-3.

- ↑ Yenne, Bill (2006). Images of America-Glacier National Park. Chicago, IL: Arcadia Publications. p. Introduction. ISBN 978-0-7385-3011-6.

- ↑ Hanna, Warren L (1986). "Exploring With Grinnell". The Life and Times of James Willard Schultz (Apikuni). Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 133–145. ISBN 0-8061-1985-3.

- ↑ Grinnell, George Bird (May–October 1901). "The Crown of the Continent". The Century Magazine. London: MacMillan and Co. 62: 660–672. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- ↑ Spence, Mark David (July 1996). "Crown of the Continent, Backbone of the World". Environmental History. Durham, NC: Forest History Society. 1 (3): 29–49 [35]. JSTOR 3985155.(registration required)

- ↑ Grinnell, George Bird (1910). History of the Boone and Crockett Club. New York, New York: Forest and Stream Publishing Co. p. 9.

- ↑ Andrew C. Harper, "The Creation of Montana's Glacier National Park," Montana: The Magazine of Western History, Summer 2010, 60#2 pp 3–24

- ↑ "Glacier Centennial 2010". National Park Service. 2009-02-17. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- ↑ Grinnell, George Bird (1910). The History of the Boone and Crockett Club. New York, New York: Forest and Stream Publishing Company. p. 49.

- ↑ Spence, Mark David (July 1996). "Crown of the Continent, Backbone of the World". Environmental History. Durham, NC: Forest History Society. 1 (3): 40–41. JSTOR 3985155.(registration required)

- ↑ Hipólito Rafael Chacón, "The Art of Glacier National Park," Montana: The Magazine of Western History, Summer 2010, Vol. 60 Issue 2, pp 56–74

- ↑ "Many Glacier Hotel Historic Structure Report" (PDF). National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. July 2002. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- ↑ Harrison, Laura Soullière (2001). "Lake McDonald Lodge". Architecture in the Parks. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- 1 2 Djuff, Ray (2001). View with a Room: Glacier's Historic Hotels and Chalets. Helena, Montana: Farcountry Press. p. 52. ISBN 1-56037-170-6.

- ↑ Harrison, Laura Soullière (1986). "Great Northern Railway Buildings". Architecture in the Parks. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- 1 2 "General Management Plan" (PDF). National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. April 1999. p. 49. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-01-27. Retrieved 2010-04-14.

- ↑ Guthrie, C. W. (2006). Going-To-The-Sun Road: Glacier National Park's Highway to the Sky. Helena, Montana: Farcountry Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-56037-335-3.

- ↑ Matthew A. Redinger, "The Civilian Conservation Corps and the Development of Glacier and Yellowstone Parks, 1933–1942," Pacific Northwest Forum, 1991, Vol. 4 Issue 2, pp 3–17

- ↑ The United States Mint Coins and Medals Program

- ↑ "Budget Justifications and Performance Information: Fiscal Year 2018" (PDF). National Park Service, The Department of the Interior. 2018. p. 156. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ↑ "Going-to-the-Sun Road project". U.S. Department of Transportation. 2010-04-14. Retrieved 2010-04-14.

- ↑ "The National Park System, Caring for the American Legacy". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2010-04-14.

- 1 2 3 4 "Mammals". National Park Service. 2008-03-05. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ "Akamina-Kishinena Provincial Park". BC Parks. Retrieved 2010-04-19.

- ↑ "Nearby Attractions". National Park Service. 2010-01-11. Retrieved 2010-04-19.

- ↑ "Great Bear Wilderness". Wilderness.net, The University of Montana. Retrieved 2010-04-19.

- 1 2 "Lakes and Ponds". Nature and Science. National Park Service. 2008-03-29. Retrieved 2010-04-19.

- ↑ "WACAP – Western Airborne Contaminants Assessment Project". National Park Service. 2010-02-25. Retrieved 2010-04-19.

- ↑ "Bird Woman Falls". World Waterfall Database. 2005-09-13. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- 1 2 "Lewis Overthrust Fault". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2010-09-03.

- 1 2 3 "Park Geology". Geology Fieldnotes. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. 2005-01-04. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- 1 2 "Geologic Formations". Nature and Science. National Park Service. 2008-03-29. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- ↑ "Glacier National Park Ranges". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- ↑ "Triple Divide Peak, Montana". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- ↑ "Exposed Rocks within the Park". America's Volcanic Past: Montana. United States Geological Survey. 2003-06-11. Retrieved 2010-04-24.

- 1 2 "History of Glaciers in Glacier National Park". Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center, United States Geological Survey. 2010-04-13. Retrieved 2010-04-24.

- ↑ "Was there a Little Ice Age and a Medieval Warm Period?". Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, United Nations Environment Programme. 2003. Retrieved 2010-04-24.

- 1 2 3 "Retreat of Glaciers in Glacier National Park". Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center, United States Geological Survey. 2010-04-13. Retrieved 2010-04-24.

- ↑ "Monitoring and Assessing Glacier Changes and Their Associated Hydrologic and Ecologic Effects in Glacier National Park". Glacier Monitoring Research. Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center, United States Geological Survey. 2010-04-13. Archived from the original on 2013-02-18. Retrieved 2010-04-24.

- 1 2 Hall, Myrna; Daniel Fagre (February 2003). "Modeled Climate-Induced glacier change in Glacier National Park, 1850–2100". 53 (2). Bioscience. Retrieved 2010-04-24.

- ↑ "Blackfoot-Jackson Glacier Complex 1914–2009". Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center, United States Geological Survey. 2010-04-13. Retrieved 2010-04-24.

- 1 2 "Montane Forest Ecotype". State of Montana. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ Landscape Photo World (October 25, 2015). "Glacier National Park". Retrieved December 8, 2015.

- ↑ "Weather". National Park Service. 2006-12-21. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ "Top Ten Montana Weather Events of the 20th Century". National Weather Service Unveils Montana's Top Ten Weather/Water/Climate Events of the 20th Century. National Weather Service. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ Fagre, Daniel (2010-04-13). "Global Change Research A Focus on Mountain Ecosystems". U.S. Geological Survey, Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ "Response of Western Mountain Ecosystems to Climatic Variability and Change: The Western Mountain Initiative" (pdf). U.S. Geological Survey, Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center. 2009-02-11. Retrieved 2014-01-12.

- ↑ "Air Quality". National Park Service. 2008-03-29. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ "Water Quality". National Park Service. 2008-03-27. Retrieved 2010-04-14.

- ↑ "MT West Glacier". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ↑ "West Glacier, Montana". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ↑ "The Crown of the Continent Ecosystem". Biodiversity. National Park Service. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- 1 2 "Plants". Nature and Science. National Park Service. 2008-03-05. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ "Wildflowers". Nature and Science. National Park Service. 2008-03-25. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ "Forests". Nature and Science. National Park Service. 2008-03-29. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- 1 2 "Whitebark Pine Communities". Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center, U.S. Geological Survey. 2010-04-13. Archived from the original on 2010-05-27. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ "If you encounter a bear". Bears. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2006-12-22. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ Hudson, Laura (2008-01-10). "Lynx inventories under way in the Intermountain Region". National Park Service. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ Kendall, Katherine; Lisette Waits (2010-04-13). "Greater Glacier Bear DNA Project 1997–2002". Northern Divide Grizzly Bear Project. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ Copeland, Jeff; Rick Yates; Len Ruggiero (2003-06-16). "Wolverine Population Assessment in Glacier National Park, Montana" (PDF). Wolverine Foundation. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- 1 2 "Mammal Checklist". Mammals of Glacier National Park Field Checklist. National Park Service. 2006-12-21. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ "Gray Wolf – Canis lupus". Montana Field Guide. State of Montana. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- 1 2 "Birds". Nature and Science. National Park Service. 2010-01-12. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ "Birds of Glacier National Park Field Checklist" (PDF). National Park Service. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-12-29. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ "Reptiles". Nature and Science. National Park Service. 2008-03-05. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ "Amphibians". Nature and Science. National Park Service. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ "Preserving Glacier's Native Bull Trout" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ "Fish". Nature and Science. National Park Service. 2008-03-05. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ "A Fire Ecosystem". Glacier National Park Wildland Fire Management. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2006-12-29. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ "Working With Fire: a look at Fire Management". Glacier National Park Wildland Fire Management. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2006-12-30. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ "Wildland Urban Interface". Glacier National Park Wildland Fire Management. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2006-12-12. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ "Fire in Glacier National Park". Glacier National Park Wildland Fire Management. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2006-12-05. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ 1930s White Glacier National Park Red Bus

- ↑ Vanderbilt, Amy M (2002). "On the Road Again: Glacier National Park's Red Buses" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-05-27. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ "History". Glacier Park Boat Company. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ Hayden, Bill (2008-10-01). "Hiking the Trails". National Park Service. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ "Trail Status Report". National Park Service. 2009-06-22. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ "Winter Hiking in Glacier National Park, Montana". Youtube. Retrieved 2011-07-08.

- ↑ "Backcountry Guide 2006" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-12-30. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ "Fishing Regulations 2008–2009" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ "Operating Hours & Seasons". National Park Service. 2010-01-05. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ Glacier Park Remembered. Montana PBS. A documentary.

- ↑ Roberts Rinehart, Mary (1915). Through Glacier Park in 1915/ Seeing America first with Howard Eaton (With Illustrations). Roberts Rinehart Publishers.

- ↑ Roberts Rinehart, Mary (1918). Tenting Tonight: A Chronicle of Sport and Adventure in Glacier Park and Cascade Mountains, with Illustrations.

Further reading

- National Park Service. "Glacier National Park".

- Parks Canada. "Waterton Lakes National Park of Canada".

- Sierra Club. "Glacier National Park is a Global Warming Laboratory". Global Warming and Energy.

- U.S. Geological Survey. "Glacier retreat in Glacier National Park, Montana". Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center research.

- U.S. Geological Survey. "Modeled Climate-Induced Glacier Change in Glacier National Park, 1850–2100".

- U.S. Geological Survey. "USGS Repeat Photography Project, Glacier National Park, MT".

- Dutiful Son: Louis W. Hill Sr. Book, Book about Louis W. Hill Sr., son and successor of empire builder James J. Hill and major force behind the establishment and development of Glacier National Park.

External links

- Bottomly-O'looney, Jennifer, and Deirdre Shaw. "Glacier National Park: People, a Playground, and a Park." Montana: The Magazine of Western History 60#1 (2010): 42–55.

- Harper, Andrew C. "Conceiving Nature: The Creation of Montana's Glacier National Park." Montana: The Magazine of Western History 60#1 (2010): 3–24.

- Glacier National Park, National Park Service homepage

- Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP). "Going-to-the-Sun Road: A Model of Landscape Engineering".

- The Kintla Archives. "The Kintla Archives: Waterton/Glacier History".

- Guide to the Glacier National Park Papers at the University of Montana

- The Glacier Institute

Media related to Glacier National Park at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Glacier National Park at Wikimedia Commons