Giordano Bruno (crater)

|

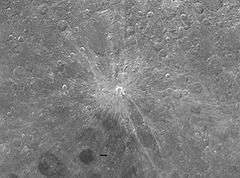

Giordano Bruno. NASA photo. | |

| Coordinates | 35°54′N 102°48′E / 35.9°N 102.8°ECoordinates: 35°54′N 102°48′E / 35.9°N 102.8°E |

|---|---|

| Diameter | 22 km |

| Depth | Unknown |

| Colongitude | 258° at sunrise |

| Eponym | Giordano Bruno |

Giordano Bruno is a 22 km lunar impact crater on the far side of the Moon, just beyond the northeastern limb. At this location it lies in an area that can be viewed during a favorable libration, although at such times the area is viewed from the side and not much detail can be seen. It lies between the craters Harkhebi to the northwest and Szilard to the southeast.

When viewed from orbit, Giordano Bruno is at the center of a symmetrical ray system of ejecta that has a higher albedo than the surrounding surface. The ray material extends for over 150 kilometers and has not been significantly darkened by space erosion. Some of the ejecta appears to extend as far as the crater Boss, over 300 km to the northwest. The outer rim of the crater is especially bright, compared to its surroundings. To all appearances this is a young formation that was created in the relatively recent past, geologically speaking. The actual age is unknown, but is estimated to be less than 350 million years.[1]

This feature was named after the Italian philosopher Giordano Bruno.

Formation

Five monks from Canterbury reported to the abbey's chronicler, Gervase, that shortly after sunset on June 18, 1178, (25 June on the proleptic Gregorian calendar) they saw "the upper horn [of the moon] split in two". Furthermore, Gervase writes:

From the midpoint of the division a flaming torch sprang up, spewing out, over a considerable distance, fire, hot coals and sparks. Meanwhile the body of the Moon which was below writhed, as it were in anxiety, and to put it in the words of those who reported it to me and saw it with their own eyes, the Moon throbbed like a wounded snake. Afterwards it resumed its proper state. This phenomenon was repeated a dozen times or more, the flame assuming various twisting shapes at random and then returning to normal. Then, after these transformations, the Moon from horn to horn, that is along its whole length, took on a blackish appearance.[2]

In 1976, the geologist Jack B. Hartung proposed that this described the formation of the crater Giordano Bruno.[3]

Modern theories predict that a (conjectural) asteroid or comet impact on the Moon would cause a plume of molten matter rising up from the surface, which is consistent with the monks' description. In addition, the location recorded fits in well with the crater's location. Additional evidence of Giordano Bruno's youth is its spectacular ray system: because micrometeorites constantly rain down, they kick up enough dust to quickly (in geological terms) erode a ray system,[4] so it can be reasonably hypothesized that Giordano Bruno was formed during the span of human history, perhaps in June 1178.

However, the question of the crater's age is not that simple. The impact creating the 22-km-wide crater would have kicked up 10 million tons of debris, triggering a week-long, blizzard-like meteor storm on Earth – yet no accounts of such a noteworthy storm of unprecedented intensity are found in any known historical records, including the European, Chinese, Arabic, Japanese and Korean astronomical archives.[5] This discrepancy is a major objection to the theory that Giordano Bruno was formed at that time.[6]

This raises the question of what the monks saw. An alternative theory holds that the monks just happened to be in the right place at the right time to see an exploding meteor coming at them and aligned with the Moon. This would explain why the monks were the only people known to have witnessed the event; such an alignment would only be observable from a specific spot on the Earth's surface.[7]

References

- ↑ Sincell, Mark (May 7, 2001). "Nothing But Moonshine". American Association for the Advancement of Science. Retrieved March 13, 2013.

- ↑ The Cosmic Winter, Clube and Napier. Blackwell Publishing, First Edition (May 1990)

- ↑ Jack B., Hartung (1976). "Was the Formation of a 20-km Diameter Impact Crater on the Moon Observed on June 18, 1178?". Meteoritics. 11 (3): 187. Bibcode:1976Metic..11..187H. doi:10.1111/j.1945-5100.1976.tb00319.x.

- ↑ Camale, O.; Mulholland, J. D. (1978). "Lunar Crater Giordano Bruno: A.D. 1178 Impact Observations Consistent with Laser Ranging Results". Science. 199 (4331): 875–87. Bibcode:1978Sci...199..875C. PMID 17757584. doi:10.1126/science.199.4331.875.

- ↑ Kettlewell, Jo (1 May 2001). "Historic lunar impact questioned". BBC. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- ↑ Stiles, Lori (April 20, 2001). "What Medieval Witnesses Saw Was Not Big Lunar Impact, Grad Student Says". University of Arizona. Retrieved March 13, 2013.

- ↑ "The Mysterious Case of Crater Giordano Bruno". NASA. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- Andersson, L. E.; Whitaker, E. A. (1982). NASA Catalogue of Lunar Nomenclature. NASA RP-1097.

- Blue, Jennifer (July 25, 2007). "Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature". USGS. Retrieved 2007-08-05.

- Bussey, B.; Spudis, P. (2004). The Clementine Atlas of the Moon. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81528-4.

- Cocks, Elijah E.; Cocks, Josiah C. (1995). Who's Who on the Moon: A Biographical Dictionary of Lunar Nomenclature. Tudor Publishers. ISBN 978-0-936389-27-1.

- McDowell, Jonathan (July 15, 2007). "Lunar Nomenclature". Jonathan's Space Report. Retrieved 2007-10-24.

- Menzel, D. H.; Minnaert, M.; Levin, B.; Dollfus, A.; Bell, B. (1971). "Report on Lunar Nomenclature by the Working Group of Commission 17 of the IAU". Space Science Reviews. 12 (2): 136–186. Bibcode:1971SSRv...12..136M. doi:10.1007/BF00171763.

- Moore, Patrick (2001). On the Moon. Sterling Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0-304-35469-6.

- Price, Fred W. (1988). The Moon Observer's Handbook. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-33500-3.

- Rükl, Antonín (1990). Atlas of the Moon. Kalmbach Books. ISBN 978-0-913135-17-4.

- Webb, Rev. T. W. (1962). Celestial Objects for Common Telescopes (6th revised ed.). Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-20917-3.

- Whitaker, Ewen A. (1999). Mapping and Naming the Moon. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-62248-6.

- Wlasuk, Peter T. (2000). Observing the Moon. Springer. ISBN 978-1-85233-193-1.

External links

- AS08-12-2209, an excellent oblique view of the ray system with Lomonosov in the foreground, from Apollo 8

- Lunar probe Kaguya overflight of Giordano Bruno crater (video)

- Giordano Bruno, The Big Picture, LRO Featured Image, June 26, 2012

- Outside of Giordano Bruno, LRO Featured Image, August 25, 2011