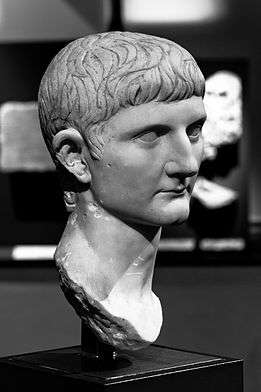

Germanicus

| Germanicus Julius Caesar | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Bust of Germanicus | |||||

| Born |

24 May 15 BC Rome, Italia, Roman Empire | ||||

| Died |

10 October AD 19 (aged 33) Antioch, Syria, Roman Empire | ||||

| Burial | Mausoleum of Augustus | ||||

| Spouse | Agrippina the Elder | ||||

| Issue | |||||

| |||||

| House | Julio-Claudian dynasty | ||||

| Father |

| ||||

| Mother | Antonia Minor | ||||

Germanicus (24 May 15 BC – 10 October AD 19), formally Germanicus Julius Caesar, was heir-designate of the Roman Empire under Tiberius and a prominent general known for his campaigns in Germania.

He was born at Rome into a prominent branch of the patrician gens Claudia, to Nero Claudius Drusus and his wife Antonia Minor. His name at birth is uncertain, but was probably Nero Claudius Drusus after his father. The agnomen Germanicus was added to his full name in 9 BC when it was posthumously awarded to his father in honor of his victories in Germania. In AD 4, he was adopted out of the Claudii and into the Julii, and his name became Germanicus Julius Caesar.

He enjoyed an accelerated political career as a Caesar, entering the office of quaestor five years before the legal age in AD 7. He held that office until AD 11, and was elected consul for the first time in AD 12. The year after, he was made proconsul of Germania Inferior, Germania Superior, and all of Gaul. From there he commanded eight legions, about one-third of the entire Roman army, which he led against the Germans in his campaigns AD 14–16. His successes made him famous after avenging the defeat of the Battle of Teutoburg Forest, and retrieving two of the three legionary eagles that had been lost during the battle. In AD 17 he returned to Rome to receive a triumph before leaving to reorganize the provinces of Asia, whereby he incorporated the provinces of Cappadocia and Commagene in AD 18.

While in the eastern provinces, he came into conflict with the governor of Syria, Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso. During their feud, Germanicus became ill in Antioch, where he died on 10 October AD 19. His death has been attributed to poison by ancient sources, but that was never proven. Beloved by the people, he was widely considered to be the ideal Roman long after his death.[1] The Roman people have been said to consider him as Rome's Alexander the Great due to the nature of his death at a young age, his virtuous character, his dashing physique and his military renown.[2][3]

Name

His praenomen is unknown, but he was probably named Nero Claudius Drusus after his father (conventionally called "Drusus"), or possibly Tiberius Claudius Nero after his uncle Tiberius.[4] In 9 BC, the agnomen Germanicus was added to his full name when it was posthumously awarded to his father in honor of his victories in Germania.[5] Though the name was inherited by his siblings too, the title seems at first to have been used exclusively by him.[6] By AD 4 he was adopted as Tiberius' son and heir. As a result, Germanicus was adopted out of the Claudii and into the Julii. In accordance with Roman naming conventions, he adopted the name "Julius Caesar" while retaining his agnomen, becoming Germanicus Julius Caesar.[note 1] Upon Germanicus' adoption into the Julii, his brother Claudius became the sole legal representative of his father, and chose to assume the title Germanicus as well.[7][8]

Family and early life

Germanicus was born in Rome on 24 May 15 BC. His father was the general Nero Claudius Drusus, the son of Livia by her first husband, Tiberius Claudius Nero. His mother was Antonia Minor, the younger daughter of the triumvir Mark Antony and Augustus' sister Octavia Minor. Germanicus had two siblings: a younger sister Livilla, and a younger brother Claudius. At the time of his birth, Livia was the third wife of Emperor Augustus and the mother of his uncle Tiberius.[9]

As a member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, he was a close relative to all five Julio-Claudian emperors. On his mother's side, he was the great-nephew of Augustus, and the nephew of Tiberius (the first and second emperors respectively). His son Gaius (known by his nickname "Caligula") would later succeed Tiberius as the third emperor. After Caligula the title passed to Germanicus' younger brother Claudius. The succession passed to Claudius' stepson Nero, the last emperor of the dynasty and a grandson of Germanicus on the side of his mother Agrippina the Younger.[10]

Germanicus was a favorite of his great-uncle Augustus who for some time considered him heir to the Empire.[10] In AD 4, persuaded by his wife Livia, Augustus decided in favor of Tiberius, his stepson from Livia's first marriage to Tiberius Claudius Nero. As a condition of Tiberius' own adoption by Augustus, Tiberius was to adopt Germanicus as a son and to name him as his heir. If Tiberius had not adopted Germanicus before his own adoption, and had Augustus adopted Tiberius first, then Tiberius would have lost sui iuris, which included the legal authority to adopt. It was a corollary to the adoption, probably the next year, that Germanicus married his maternal second cousin, Agrippina the Elder.[11][12]

By his wife Agrippina, a granddaughter of Augustus, he had nine children: Nero Julius Caesar, Drusus Caesar, Tiberius Julius Caesar (not to be confused with emperor Tiberius), a child of unknown name (normally referenced as Ignotus), Gaius the Elder, the Emperor Caligula (Gaius the Younger), the empress Agrippina the Younger, Julia Drusilla, and Julia Livilla. Only six of his children came of age; Tiberius and the Ignotus died as infants, and Gaius the Elder in his early childhood.[10]

Career

Batonian War

.svg.png)

Germanicus was given the title of quaestor in AD 7, five years before the legal age of 25,[13] and in that year was sent to assist Tiberius in the war against the Pannonians and Dalmatians.[14] According to Cassius Dio, Augustus sent Germanicus to Illyricum because Tiberius' lack of activity made Augustus suspect that he was delaying to remain under arms as long as possible under the pretense of war.[15] Germanicus brought an army of levied citizens and manumitted slaves that were bought from their masters to reinforce Tiberius in Siscia, his base of operations in Illyricum. In late autumn/early winter additional reinforcements arrived at Siscia from Moesia and the East: three legions from Moesia led by Severus and two from Anatolia led by Silvanus with Thracian cavalry and auxiliary troops. While this did show that Augustus took the threat seriously, Tiberius had some soldiers sent back, because he had more than he needed.[16][17]

Not long after Germanicus reached Pannonia, Severus was attacked in Moesia, but successfully repelled the rebels. By the time Germanicus arrived the rebels had withdrawn to mountain fortresses from which they launched raids. The Romans were tactically unsuited at countering raids, so Tiberius had to utilize his auxiliary forces and divided his army into small detachments to cover more ground. Tiberius appears to have been conducting a war of attrition against the rebels who were now occupying strong defensive positions. In addition, the Romans began working to drive the rebels out of the countryside offering forgiveness to any tribes that would lay down their arms, and a scorched earth policy was implemented through which Tiberius may have been hoping to starve the enemy out. While most of his detachments saw little action at the time, Germanicus did defeat the Mazaei, a Dalmatian tribe.[17][18]

AD 8 saw the collapse of the rebel position in Pannonia: a rebel commander, Bato the Breucian, surrendered their leader Pinnes to the Romans and laid down his arms in return for amnesty from the Romans. Bato the Breucian was left in charge of his people and some additional Pannonians. This was a significant event in the war, considering the large population and resources of the Breuci, who were able to supply the Roman army with eight cohorts alone toward the end of the conflict.[17] Bato the Breucian was himself defeated in battle and subsequently executed by his former ally Bato the Daesitiate. As a result of the surrender of Pinnes and the death of Bato the Breucian, the Pannonians were divided against each other, and the Romans attacked, and conquered the Breuci without battle. Bato the Daesitiate withdrew from Pannonia to Dalmatia, where he occupied the mountains of Bosnia and began conducting counter-attacks, most likely against the indigenous people who sided with the Romans. Later in the year, Tiberius left Lepidus in command of Siscia and Silvanus at Sirmium.[19][20]

Roman forces took the initiative in AD 9, and pushed into Dalmatia. Tiberius divided the forces into three divisions, two under Silvanus (south-east from Sirmium) and Lepidus (north-west from Siscia), and the third led by himself with Germanicus in the Dalmatian hinterland. The divisions under Lepidus and Silvanus easily defeated their foes, having nearly exterminated the Perustae and Daesitiate, two Dalmatian tribes held up in mountain strongholds.[21] Roman forces captured many cities, with Germanicus himself taking Raetinum (which was lost in a fire set by the enemies during the siege; near Seretium), Splonum (in northern Montenegro), and Seretium (in western Bosnia).[22] Meanwhile, Germanicus and Tiberius pursued Bato until he made a stand at a fortress called Adetrium near Salona, to which the Caesars laid siege. When it became clear he would not surrender, Tiberius attacked the fortress, using a steady supply of reinforcements. The fortress was overwhelmed and the defenders were killed. While Tiberius negotiated the terms of capitulation, Germanicus went on a punitive expedition across the surrounding territory in which he besieged the fortified town of Arduba, defeating it and obtaining their surrender and that of surrounding towns. He returned to Tiberius, and sent a Postumius to subdue the remaining districts.[23][24]

Interim

After a distinguished commencement to his military career, he returned to Rome in AD 10 to personally announce his victory, whereupon he was honored with a triumphal insignia (without an actual triumph) and the rank (not the actual title) of praetor, with permission to be a candidate for consul before the regular time.[14] In addition, he was given the right to speak first in the Senate after consuls.[5]

According to Cassius Dio, Germanicus became popular in his capacity as quaestor, because he acted as an advocate for people just as much before Augustus as before the other judges. There was a case in AD 10 when he was the defense advocate for a quaestor accused of murder. The accuser demanded a trial before Augustus himself as a sort of "appeal to Caesar", fearing the jurors would vote in favor of the defense out of deference for Germanicus. A tribunal before Augustus was held, but the accuser lost anyway. This is evidence of a capital jurisdiction held by Augustus separate from the standard quaestiones ("trials").[26]

The successes in Illyricum were followed by the defeat of Varus at the Battle of Teutoburg Forest. As proconsul, Germanicus was dispatched with Tiberius to defend the empire against the Germans in AD 11. The two generals crossed the Rhine, made various excursions into enemy territory and, in the beginning of autumn, recrossed the river. In winter, Germanicus returned to Rome, where he was appointed consul for the year AD 12, after five mandates as quaestor, and despite never having been aedile or praetor. He shared the consulship with Gaius Fonteius Capito.[14][27][28]

During his consulship he advocated for the accused in court, which was a popular move, reminiscent of when he formerly used to plea for his defendants directly to Augustus. He also appealed to the people by ministering the Ludi Martiales (games of Mars), where he let loose two hundred lions in the Circus Maximus. Pliny the Elder mentions the games in his Historia Naturalis.[14][29][30]

On 16 January AD 13, Tiberius held a triumph for their victory over the Pannonians and Dalmatians, that he had postponed on account of the defeat of Varus at Teutoburg Forest. He was accompanied by Germanicus among his other generals, for whom he had obtained the triumphal regalia, and Germanicus took a distinguished part in the celebration. He was given the opportunity to display his consular insignia and his triumphal ornaments whereas his brother Drusus received no special honors except being the son of a triumphator.[14][30][31]

Commander of Germania

_en.png)

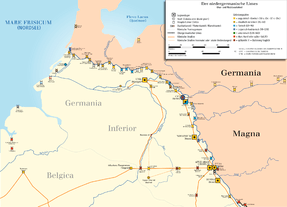

In AD 13, Augustus appointed him commander of the forces in the Rhine, which totaled eight legions and was about one-third of Rome's total military force.[32] The next year in August, Augustus died and on 17 September the Senate met to confirm Tiberius as princeps. That day the Senate also dispatched a delegation to Germanicus' camp to send its condolences for the death of his grandfather, and more importantly, to grant him proconsular imperium. The delegation would not arrive until October.[33]

In Germany and Illyricum, the legions were in mutiny. In Germany, the legions in mutiny were those of the Lower Rhine under Aulus Caecina (the V Alaudae, XXI Rapax, I Germanica, and XX Valeria Victrix). The army of the Lower Rhine was stationed in summer quarters on the border of the Ubii.[32] They had not gotten the bonuses promised them by Augustus, and when it became clear a response from Tiberius was not forthcoming, they revolted. Germanicus dealt with the troops in Germania, and Tiberius' son Drusus dealt with Illyricum.[34][35]

The army of the Lower Rhine sought an increase in pay, the reduction of their service to 16 years (down from 20) to mitigate the hardship of their military tasks, and vengeance against the centurions for their cruelty. After arriving to their camp, the soldiers listed their complaints and attempted to proclaim him emperor. His open and affable manners made him popular with the soldiers, but he remained loyal to the emperor. When news of the mutiny reached the army of the Upper Rhine under Gaius Silius (the Legions II Augusta, XIII Gemina, XVI Gallica, and XIV Gemina) a meeting was held to meet their demands. Germanicus negotiated a settlement:[14][36][37]

- After 20 years of service, a full discharge was given, but after 16 years an immunity from military tasks, except to take part in actions (missio sub vexillo).

- The legacy left by Augustus to the troops was to be doubled and discharged.

First campaign against the Germans

To satisfy the requisition promised to the legions, Germanicus paid them out of his own pocket. All 8 legions were given money, even if they didn't demand it. Both the armies of the Lower and Upper Rhine had returned to order. It seemed prudent to satisfy the armies, but Germanicus took it a step further. In a bid to secure the loyalty of his troops, he led them on a raid against the Marsi, a Germanic people on the upper Ruhr river. Germanicus massacred the villages of the Marsi he encountered and pillaged the surrounding territory. On the way back to their winter quarters at Castra Vetera, they pushed successfully through the opposing tribes (Bructeri, Tubantes, and Usipetes) between the Marsi and the Rhine.[38][39][40]

Back at Rome, Tiberius instituted the Sodales Augustales, a priesthood of the cult of Augustus which Germanicus became a member of.[41] When news arrived of his raid, Tiberius commemorated his services in the Senate with elaborate, but insincere praise: the proceedings gave him joy that the mutiny had been suppressed, but anxiety at the glory and popularity afforded to Germanicus. The Senate, in absence of Germanicus, voted that he should be given a triumph.[42][43] Ovid's Fasti dates the Senate vote of Germanicus' triumph to 1 January AD 15.[44]

Second campaign against the Germans

For the next two years, he led his legions across the Rhine against the Germans, where they would confront the forces of Arminius and his allies. Tacitus says the purpose of those campaigns were to avenge the defeat of Varus at the Battle of Teutoburg Forest, and not to expand Roman territory.[32][45]

In early spring AD 15, Germanicus crossed the Rhine and struck the Chatti. He sacked their capital Mattium (modern Maden near Gudensberg), pillaged their countryside, then returned to the Rhine. Sometime this year, he received word from Segestes, who was held prisoner by Arminius' forces and needed help. Germanicus' troops released Segestes and took his pregnant daughter, Arminius' wife Thusnelda, into captivity. Again he marched back victorious and at the direction of Tiberius, accepted the title of Imperator.[32][43]

Arminius called his tribe, the Cherusci, and the surrounding tribes to arms. Germanicus coordinated a land and riverine offensive, with troops marching eastward across the Rhine, and sailing from the North Sea up the Ems River in order to attack the Bructeri and Cherusci.[46] Germanicus' forces went through Bructeri territory, where a general Lucius Stertinius recovered the lost eagle of the XIX Legion from among the equipment of the Bructeri after routing them in battle.[47][48]

Germanicus' divisions met up to the north, and ravaged the countryside between the Ems and the Lippe, and penetrated to the Teutoburg Forest, a mountain forest in Western Germany situated between these two rivers.[43] There, Germanicus and some of his men visited the site of the disastrous Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, and began burying the remains of the Roman soldiers that had been left in the open. After half a day of the work, he called off the burial of bones so that they could continue their war against the Germans.[49] He made his way into the heartland of the Cherusci. At a location Tacitus calls the pontes longi ("long causeways"), in boggy lowlands somewhere near the Ems, Arminius' troops attacked the Romans. Arminius initially caught Germanicus' cavalry in a trap, inflicting minor casualties, but the Roman infantry reinforced the rout and checked them. The fighting lasted for two days, with neither side achieving a decisive victory. Germanicus' forces withdrew and returned to the Rhine.[43][46][note 2]

Third campaign against the Germans

In preparations for his next campaign, Germanicus sent Publius Vitellius and Gaius Antius to collect taxes in Gaul, and instructed Silius, Anteius, and Caecina to build a fleet. A fort on the Lippe called Castra Aliso was besieged, but the attackers dispersed on sight of Roman reinforcements. The Germans destroyed the nearby mound and altar dedicated to his father Drusus, but he had them both restored and celebrated funerary games with his legions in honor of his father. New barriers and earthworks were put in place, securing the area between Fort Aliso and the Rhine.[43]

Germanicus commanded eight legions with auxiliary units overland across the Rhine, up the Ems and Weser rivers as part of his last major campaign against Arminius in AD 16. His forces met those of Arminius on the plains of Idistaviso, by the Weser River near modern Rinteln, in an engagement called the Battle of the Weser River. Tacitus says that the battle was a Roman victory:[50][51]

the enemy were slaughtered from the fifth hour of daylight to nightfall, and for ten miles the ground was littered with corpses and weapons.

Shortly after the battle, the sides met at a place Tacitus called the Angivarian Wall further downstream on the Weser (west of modern Hanover). According to Tacitus, the Romans won, but the victory was indecisive. Germanicus sent some troops back to the Rhine, with some of them taking the land route, but most of them took the fast route and traveled by boat. They went down the Ems toward the North Sea, but as they reached the sea, a storm struck, sinking most of the boats and killing many men and horses.[43][50]

A few more raids were launched across the Rhine, which resulted in the recovery of another of the three legion's eagles lost in AD 9. Germanicus' successes in Germany had made him popular with the soldiers. He had dealt a significant blow to Rome's enemies, quelled an uprising of troops, and returned lost standards to Rome. His actions had increased his fame, and he had become very popular with the Roman people. Tiberius took notice, and had Germanicus recalled to Rome and informed him that he would be given a triumph and reassigned to a different command.[52]

Result

While Germanicus enjoyed some success in his campaigns against Arminius and his allies, Tiberius decided not to conquer the Germans and recalled Germanicus to Rome. The effort it would have taken to conquer Germania Magna was too great when compared with the low potential for profit from acquiring the new territory. Rome regarded Germany as a wild territory of forests and swamps, with little wealth compared to territories Rome already had.[53] However, the campaign significantly healed the Roman psychological trauma from the Varus disaster, and greatly recovered Roman prestige. In addition to the recovery of two of the three lost eagles, he fought Arminius, the leader who destroyed the three Roman legions in 9 AD, and defeated him. In leading his troops across the Rhine without recourse to Tiberius, he contradicted the advice of Augustus to keep that river as the boundary of the empire, and opened himself to potential doubts from Tiberius about his motives in taking such independent action. This error in political judgement gave Tiberius reason to controversially recall his nephew.[52] Tacitus, with some bitterness, asserts that had Germanicus been given full independence of action, he could have completed the conquest of Germania.[54][55]

Recall

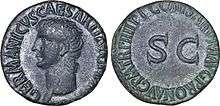

At the beginning of AD 17, Germanicus returned to the capital and on May 26 he celebrated a triumph for his victories over the Germans. He had captured a few important prisoners, but Arminius was still at large. It was far from clear that Germanicus had won the war. Nonetheless, this did not take away from the spectacle of his triumph: a near contemporary calendar marks 26 May as the day in "which Germanicus Caesar was born into the city in triumph", while coins issued under his son Gaius (Caligula) depicted him on a triumphal chariot, with the reverse reading "Standards Recovered. Germans Defeated."[57]

His triumph included a long procession of captives including the wife of Arminius, Thusnelda, and her three-year-old son, among others of the defeated German tribes.[note 3] The procession displayed replicas of mountains, rivers, and battles; and the war was considered closed.[58]

Tiberius gave money out to the people of Rome in his name, and he was scheduled to hold the consulship next year with the emperor. As a result, in AD 18, Germanicus was granted the eastern part of the empire, just as Agrippa and Tiberius had received before, when they were successors to the emperor.[59]

Command in Asia

Following his triumph, Germanicus was sent to Asia to reorganize the provinces and kingdoms of Asia, which were in such disarray that the attention of a domus Augusta was deemed necessary to settle matters.[note 4] Germanicus was given imperium maius (extraordinary command) over the other governors and commanders of the area he was to operate; however, Tiberius had replaced the governor of Syria with Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso, who was meant to be his helper (adiutor), but turned out to be hostile.[60] According to Tacitus, this was an attempt to separate Germanicus from his familiar troops and weaken his influence, but the historian Richard Alstonsays Tiberius had little reason to undermine his heir.[61]

Not waiting to take up his consulship in Rome, he left after his triumph but before the end of AD 17. He sailed down the Illyrian coast of the Adriatic Sea to Greece, where he restored the temple of Spes, and won a chariot race at the Olympic games that year. He arrived at Nicopolis near the site of the Battle of Actium, where he took up his second consulship on 18 January AD 18. He visited the sites associated with his adoptive grandfather Augustus and his natural grandfather Marc Antony, before crossing the sea to Lesbos and then to Asia Minor. There he visited the site of Troy and the oracle of Apollo Claros near Colophon. Piso left at the same time as Germanicus, but traveled directly to Athens and then to Rhodes where he and Germanicus met for the first time. From there Piso left for Syria where he immediately began replacing the officers with men loyal to himself in a bid to win the loyalty of his soldiers.[60][62]

Next Germanicus traveled through Syria to Armenia where he installed king Artaxias as a replacement for Vonones, whom Augustus had deposed and placed under house arrest at the request of the king of Parthia, Artabanus. The king of Cappadocia died too, whereupon Germanicus sent Quintus Veranius to organize Cappadocia as a province – a profitable endeavor as Tiberius was able to reduce the sales tax down to .5% from 1%. The revenue from the new province was enough to make up the difference lost from lowering the sales tax. The Kingdom of Commagene was split on whether or not to remain free or to become a province with both sides sending deputations, so Germanicus sent Quintus Servaeus to organize the province.[63][64][65]

Having settled these matters he traveled to Cyrrhus, a city in Syria between Antioch and the Euphrates, where he spent the rest of AD 18 in the winter quarters of the Legion X Fretensis.[66] Evidently here Piso attended Germanicus, and quarreled because he failed to send troops to Armenia when ordered. Artabanus sent an envoy to Germanicus requesting the Vonones be moved further from Armenia as to not incite trouble there. Germanicus complied, moving Vonones to Cilicia, both to please Artabanus and to insult Piso who Vonones was friendly with.[67][68]

Egypt

.jpg)

He then made way to Egypt, arriving to a tumultuous reception in January AD 19. He had gone there to relieve a famine in the country vital to Rome's food supply. The move upset Tiberius, because it had violated an order by Augustus that no senator shall enter the province without consulting the emperor and the Senate (Egypt was an imperial province, and belonged to the emperor).[note 5] He returned to Syria by summer, where he found that Piso had either ignored or revoked his orders to the cities and legions. Germanicus in turn ordered Piso's recall to Rome, although this action was probably beyond his authority.[67][69]

In the midst of this feud, Germanicus became ill and despite the fact Piso had removed himself to the port of Seleucia, he was convinced that Piso was somehow poisoning him. Tacitus reports that there were signs of black magic in Piso's house with hidden body parts and Germanicus' name inscribed on lead tablets.[70] Germanicus sent Piso a letter formally renouncing their friendship (amicitia). Germanicus died soon after on 10 October of that year.[67] His death aroused much speculation, with several sources blaming Piso, acting under orders from Emperor Tiberius. This was never proven, and Piso later died while facing trial. Tiberius feared the people of Rome knew of the conspiracy against Germanicus, but Tiberius' jealousy and fear of his nephew's popularity and increasing power was the true motive as understood by Tacitus.[71]

The death of Germanicus in dubious circumstances greatly affected Tiberius' popularity in Rome, leading to the creation of a climate of fear in Rome itself. Also suspected of connivance in his death was Tiberius' chief advisor, Sejanus, who would, in the 20s, create an atmosphere of fear in Roman noble and administrative circles by the use of treason trials and the role of delatores, or informers.[72]

Post mortem

When Rome had received word of Germanicus' death, the people began observing a iustitium before the Senate had officially declared it. Tacitus says this shows the true grief that the people of Rome felt,[73] and this also shows that by this time the people already knew the proper way to commemorate dead princes without an edict from a magistrate.[74] At his funeral, there were no procession statues of Germanicus. There were abundant eulogies and reminders of his fine character and a particular eulogy was given by Tiberius himself in the Senate.[75]

The historians Tacitus and Suetonius record the funeral and posthumous honors of Germanicus. His name was placed into the Carmen Saliare, and onto the Curule chairs that were placed with oaken garlands over them as honorary seats for the Augustan priesthood. His ivory statue was at the head of the procession during the Circus Games; his posts as priest of Augustus and Augur were to be filled by members of the imperial family; knights of Rome gave his name to a block of seats at a theatre in Rome, and rode behind his effigy on 15 July AD 20.[76]

After consulting with his family, Tiberius made his wishes known whereupon the Senate collected the honors into a commemorative decree, the Senatus Consultum de memoria honoranda Germanini Caesaris, and ordered the consuls of AD 20 to issue a public law honoring the death of Germanicus, the Lex Valeria Aurelia. Although Tacitus stressed the honors paid to him, the funeral and processions were carefully modeled after those of Gaius and Lucius, Agrippa's sons. This served to emphasize the continuation of the domus Augusta across the transition from Augustus to Tiberius. Commemorative arches were built in his honor and not just at Rome, but at the frontier on the Rhine and in Asia where he had governed in life. The arch of the Rhine was placed alongside of that of his father, where the soldiers had built a funerary monument honoring him. Portraits of him and his natural father were placed in the Temple of Apollo on the Palatine in Rome.[74][76]

On the day of Germanicus' death his sister Livilla gave birth to twins by Drusus. The oldest was named Germanicus and died young. In 37, Germanicus' only remaining son Caligula became emperor and renamed September Germanicus in honor of his father.[6] Many Romans, in the account of Tacitus, considered Germanicus to be their equivalent to King Alexander the Great, and believed that he would have easily surpassed the achievements of Alexander had he become emperor.[3] In book eight of his Natural History, Pliny connects Germanicus, Augustus, and Alexander as fellow equestrians: when Alexander's horse Bucephalus died he named a city Bucephalia in his honor. Less monumental, Augustus' horse received a funeral mound, which Germanicus wrote a poem about.[77]

Trial of Piso

Piso was rumored to have been responsible for his death and with accusations coming in it wasn't long before the well known accuser, Lucius Fulcinius Trio, brought charges against him. The Pisones were longtime supporters of the Claudians, and had allied themselves with Octavian early on. The continued support of the Pisones and his own friendship to Piso made him hesitant to hear the case himself. After briefly hearing both sides, Tiberius deferred the case to the Senate, making no effort to hide his deep anger toward Piso. Tiberius made allowances for Piso to summon witnesses of all social orders, including slaves, and he was given more time to plea than the prosecutors, but it made no difference: before the trial was over Piso died ostensibly by suicide, but Tacitus supposes Tiberius may have had him murdered before he could implicate the emperor in Germanicus' death.[78][79][80]

The accusations brought against Piso are numerous, including:[81][note 6]

- Insubordination

- Corruption

- Abandoning and reentering a province

- Summary justice

- Destroying military discipline

- Misusing the fiscus principis (emperor's money)

- Fomenting civil war

- Violating the divinity of Divus Augustus (sacrilege).

He was found guilty and punished posthumously for the crime of treason. The Senate had his property proscribed, forbade mourning on his account, removed images of his likeness, such as statues and portraits, and his name was erased from the base of one statue in particular as part of his damnatio memoriae. Yet, in a show of clemency not unlike that of the emperor, the Senate had Piso's property returned and divided equally between his two sons, on condition that his daughter Calpurnia be given 1,000,000 sesterces as dowry and a further 4,000,000 as personal property. His wife Placina was absolved.[81][82]

Literary activity

In AD 4, Germanicus wrote a Latin version of Aratus's Phainomena, which survives, wherein he rewrites the contents of the original. For example, he replaces the opening hymn to Zeus with a passage in honor of the Roman emperor.[83] He avoided writing in the poetic style of Cicero, who had translated his own version of the Phainomena, and he wrote in a new style to meet the expectations of a Roman audience whose tastes were shaped by "modern" authors like Ovid and Virgil.[84] For his work, Germanicus is ranked among Roman writers on astronomy, and his work was popular enough for scholia to be written on it well into the Medieval era.[85]

Historiography

Germanicus and Tiberius are often contrasted by ancient historians, poets who wrote using themes found in drama, with Germanicus playing the tragic hero and Tiberius the tyrant. The endurance of the Principate is challenged in these narratives, by the emperor's jealous trepidation toward competent commanders such as Germanicus. Attention is paid particularly to their leadership styles, i.e., in their relationship with the masses. Germanicus is painted as a competent leader able to handle the masses whereas Tiberius is indecisive and envious.[86][87]

Despite the poetics attached to Germanicus by ancient authors, it is accepted by historians such as Anthony Barrett that Germanicus was an able general. He fought against the Pannonians under Tiberius, quelled the mutiny in the Rhine, and led three successful campaigns into Germania. As for his popularity, he was popular enough that the mutinous legions of the Rhine attempted to proclaim him emperor in AD 14; however, he remained loyal and led them against the German tribes instead. Tacitus and Suetonius claim that Tiberius was jealous of Germanicus' popularity, but Barrett suggests their claim might be contradicted by the fact that, following his campaigns in Germany, Germanicus was given command of the eastern provinces – a sure sign he was intended to rule. In accordance with the precedent set by Augustus, Agrippa had been given command of those same provinces in the east when Agrippa was the intended successor to the empire.[14][88]

Publius Cornelius Tacitus

The Annals by Tacitus is one of the most detailed accounts of Germanicus' campaigns against the Germans. He wrote his account in the early years of the second century. Tacitus described Germanicus as a fine general who was kind and temperate, saying that his early death had taken a great ruler from Rome.[2][47]

Book 1 of Annals extensively focuses on the mutinies of the legions in Pannonia and Germany (AD 14). The riotous army figures into the unpredictable wrath of the Roman people giving Tiberius the chance to reflect on what it means to lead. It serves to contrast the "old-fashioned" Republican values assigned to Germanicus, and the imperial values possessed by Tiberius. The mood of the masses is a recurring theme, with their reactions to the fortunes of Germanicus being a prominent feature of the relationship between him and Tiberius well into the Annals (as far as Annals 3.19).[86]

Suetonius Tranquillus

Suetonius was an equestrian who held administrative posts during the reigns of Trajan and Hadrian. The Twelve Caesars details a biographical history of the principate from the birth of Julius Caesar to the death of Domitian in AD 96. Like Tacitus, he drew upon the imperial archives, as well as histories by Aufidius Bassus, Cluvius Rufus, Fabius Rusticus and Augustus' own letters.[89]

The attitude of Suetonius toward Germanicus' personality and moral temperament is that of adoration. He dedicates a good portion of his Life of Caligula to Germanicus, claiming Germanicus' physical and moral excellence surpassed that of his contemporaries. Suetonius also says that Germanicus was a gifted writer, and that despite all these talents, he remained humble and kind.[88][90]

Legacy

Due to his prominence as heir to the imperial succession, he is depicted in many works of art. He often appears in literature as the archetypal ideal Roman.[91] His life and character have been portrayed in many works of art, the most notable of which include:

- Germanico in Germania (1732), an Italian opera by Nicola Porpora. He was played by Domenico Annibali.[92]

- Thusnelda im Triumphzug des Germanicus (1873), a painting by German painter Karl von Piloty.[56]

- I, Claudius (1934), a historical fiction novel by classicist Robert Graves.[93]

- The Caesars (1968), a television series by Philip Mackie. He was played by Eric Flynn.[94]

- I, Claudius (1976), a television series by Jack Pulman. He was played by David Robb.[95]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Germanicus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Footnotes

- ↑ His agnomen, "Germanicus", was a cognomen ex virtue, and would at first be a suffix at the end of his full name, and became the first part of his full name following his adoption into the Julii, as his original praenomen and nomen were removed, "Germanicus" was retained, and thus attained usage as his praenomen preceding the new additions (the nomen "Julius", and cognomen "Caesar", respectively) (Possanza 2004, p. 225). Smith 1880, p. 258: "In subsequent coins he becomes stylized as Germanicus Caesar, Ti. Aug. F. Divi Aug. N."

- ↑ Tacitus claims that the Romans won the battle at pontes longi (Tacitus, I.63); however, modern sources say the battle was inconclusive (Wells 2003, p. 206; Smith 1880, p. 259).

- ↑ Captives featured in the triumph include: "Segimuntus, the son of Segestes, the chief of the Cherusci, and his sister, named Thusnelda, the wife of Armenius, who led on the Cherusci when they treacherously attacked Quintilius Varus, and even to this day continues the war; likewise his son Thumelicus, a boy three years old, as also Sesithacus, the son of Segimerus, chief of the Cherusci, and his wife Rhamis, the daughter of Ucromirus, chief of the Chatti, and Deudorix, the son of Bætorix, the brother of Melon, of the nation of the Sicambri; but Segestes, the father-in-law of Armenius, from the commencement opposed the designs of his son-in-law, and taking advantage of a favorable opportunity, went over to the Roman camp and witnessed the triumphal procession over those who were dearest to him, he being held in honor by the Romans. There was also led in triumph Libes the priest of the Chatti, and many other prisoners of the various vanquished nations, the Cathylci and the Ampsani, the Bructeri, the Usipi, the Cherusci, the Chatti, the Chattuarii, the Landi, the Tubattii." (Strabo, Geography, VII.4.33–38)

- ↑ Domus Augusta (lit. "House of Augustus") was the family of Tiberius including cognate relations (Cascio 2005, p. 140).

- ↑ That he violated this order is possibly confirmed by the fact that the trip is omitted in Germanicus' res gestae in the Senatus Consultum de memoria honoranda Germanini Caesaris, a commemorative decree issued by the Senate and approved by Tiberius following his death (Lott 2012, p. 343).

- ↑ Despite the exhaustive list only two statutes are mentioned: that of Piso violating Germanicus' imperium, as he officially held greater authority despite both of them being of proconsular rank; and treason, which violated the lex Iulia maiestatis for moving troops out of his province without authorization to wage war (Rowe 2002, p. 11 and Ando, Tuori & Plessis 2016, p. 340).

References

- ↑ Barrett 1993, p. 27

- 1 2 Tacitus, The Annals, II.73

- 1 2 Barrett 2015, p. 20

- ↑ Simpson 1981, p. 368

- 1 2 Swan 2004, p. 249

- 1 2 Smith 1880, p. 257

- ↑ Gibson 2013, p. 9

- ↑ Suetonius, Claudius 2

- ↑ Meijer 1990, pp. 576–7

- 1 2 3 Salisbury 2001, p. 3

- ↑ Swan 2004, p. 142

- ↑ Levick 1999, p. 33

- ↑ Pettinger 2012, p. 65

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Smith 1880, p. 258

- ↑ Cassius Dio, Roman History, LV.31.1

- ↑ Crook 1996, p. 107

- 1 2 3 Dzino 2010, p. 151

- ↑ Radman-Livaja & Dizda 2010, pp. 47–48

- ↑ Cassius Dio, Roman History, LV.34.4–7

- ↑ Dzino 2010, pp. 151–152

- ↑ Velleius Paterculus, Compendium of Roman History, 2.114.5, 115-1-4

- ↑ Swan 2004, pp. 240–241

- ↑ Cassius Dio, Roman History, LVI.11–16

- ↑ Dzino 2010, pp. 152–153

- ↑ Chrystal 2015, p. 153

- ↑ Swan 2004, p. 276

- ↑ Wells 2003, pp. 202–3

- ↑ Gibson 2013, pp. 80–82

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, Historia Naturalis, ii. 26

- 1 2 Gibson 2013, pp. 82

- ↑ Suetonius, Tiberius 20

- 1 2 3 4 Wells 2003, p. 204

- ↑ Levick 1999, pp. 50–53

- ↑ Cassius Dio, Roman History, LVII.6

- ↑ Pettinger 2012, p. 190

- ↑ Pettinger 2012, p. 189

- ↑ Alston 1998, p. 25

- ↑ Smith 1880, pp. 258–259

- ↑ Velleius Paterculus, Compendium of Roman History, ii. 125

- ↑ Dando-Collins 2010, p. 183

- ↑ Rowe 2002, p. 89

- ↑ Dando-Collins 2008, p. 6

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Smith 1880, p. 259

- ↑ Herbert-Brown 1994, p. 205

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals I.43

- 1 2 Wells 2003, pp. 204–205

- 1 2 Wells 2003, p. 42

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals, I.60

- ↑ Wells 2003, pp. 196–197

- 1 2 Wells 2003, p. 206

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals, II.18

- 1 2 Shotter 1992, pp. 35–37

- ↑ Wells 2003, pp. 206–207

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals II.88

- ↑ Bowman, Champlin & Lintott 1996, p. 209

- 1 2 Beard 2007, p. 108

- ↑ Beard 2007, pp. 107–109

- ↑ Beard 2007, p. 167

- ↑ Alston 1998, p. 25

- 1 2 Lott 2012, p. 342

- ↑ Alston 1998, pp. 25–26

- ↑ Barrett 1993, p. 12

- ↑ Barrett 1993, p. 14

- ↑ Tabula Siarensis, 113–114

- ↑ Suetonius, Caligula 1

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals II.57.1

- 1 2 3 Lott 2012, p. 343

- ↑ Barrett 1993, p. 50

- ↑ Shotter 1992, p. 38

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals II.69

- ↑ Lott 2012, p. 40

- ↑ Ward, Heichelheim & Yeo 2010, p. 297

- ↑ Tacitus, The Annals, II.82

- 1 2 Lott 2012, p. 19

- ↑ Levick 2012, p. 105

- 1 2 Tacitus, The Annals, II.83

- ↑ Heckel & Tritle 2009, p. 261

- ↑ Suetonius, Tiberius 52

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals III.15-16

- ↑ Shotter 1992, pp. 41–44

- 1 2 Rowe 2002, pp. 9–17

- ↑ Ando, Tuori & Plessis 2016, p. 340

- ↑ Possanza 2004, p. 10

- ↑ Possanza 2004, p. 116

- ↑ Dekker 2013, p. 4

- 1 2 Miller & Woodman 2010, pp. 11–13

- ↑ Mehl 2011, p. 146

- 1 2 Barrett 1993, pp. 19–20

- ↑ Suetonius, Life of Tiberius 43-45

- ↑ Suetonius, Life of Caligula 3

- ↑ Perrottet 2002, p. 369

- ↑ Robinson & Monson 1992, pp. 1065–1067

- ↑ Perrottet 2002, p. 20

- ↑ Vahimagi & Grade 1996, p. 162

- ↑ Newcomb 1997, p. 1157

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Cassius Dio, Roman History Books 55–57, English translation

- Suetonius, Lives of the Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula, Latin text with English translation

- Suetonius, Lives of the Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius, Latin text with English translation

- Tacitus, Annals, I–VI, English translation

- Velleius Paterculus, Roman History Book II, Latin text with English translation

Secondary sources

- Alston, Richard (1998), Aspects of Roman History AD 14–117, Routledge, ISBN 0-203-20095-0

- Chrystal, Paul (2015), Roman Military Disasters: Dark Days & Lost Legions, Pen & Sword Military, ISBN 978-1-47382-357-0

- Ando, Clifford; Tuori, Kaius; Plessis, Paul J. du, eds. (2016), Oxford Handbook of Law and Society, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-872868-9

- Barrett, Anthony A. (1993), Caligula: The Corruption of Power, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-21485-8

- Barrett, Anthony A. (2015), Caligula: The Abuse of Power, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-65844-7

- Beard, Mary (2007), The Roman Triumph, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-02613-1

- Bowman, Alan K.; Champlin, Edward; Lintott, Andrew (1996), The Cambridge Ancient History, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-26430-8

- Cascio, Elio Lo, ed. (2005), "The Domus Augusta and the Dynastic Ideology", The Cambridge Ancient History: Volume 12, The Crisis of Empire, AD 193–337, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-30199-8

- Crook, J.A., ed. (1996), "Political History, 30 B.C. to A.D. 14", The Cambridge Ancient History: Volume X, The Augustan Empire, 43 B.C. – A.D. 69, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-26430-8

- Dando-Collins, Stephen (2008), Blood of the Caesars: How the Murder of Germanicus Led to the Fall of Rome, Wiley, ISBN 9780470137413

- Dando-Collins, Stephen (2010), Legions of Rome, Quercus, ISBN 978-1-62365-201-2

- Dekker, Elly (2013), Illustrating the Phaenomena: Celestial cartography in Antiquity and the Middle Ages, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-960969-7

- Dzino, Danijel (2010), Illyricum in Roman Politics, 229 BC-AD 68, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-19419-8

- Gibson, Alisdair (2013), The Julio-Claudian Succession: Reality and Perception of the "Augustan Model", Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-23191-7

- Heckel, Waldemar; Tritle, Lawrence A. (2009), Alexander the Great: A New History, Blackwell Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4051-3081-3

- Herbert-Brown, Geraldine (1994), Ovid and the Fasti: An Historical Study, Clarendon Press Oxford, ISBN 0-19-814935-2

- Levick, Barbara (1999), Tiberius the Politician, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-21753-9

- Levick, Barbara (2012), Claudius, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-41516619-5

- Lott, J. Bert (2012), Death and Dynasty in Early Imperial Rome: Key Sources, with Text, Translation, and Commentary, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-86044-4

- Mehl, Andreas (2011), Roman Historiography, translated by Mueller, Hans-Friedrich, Blackwell Publishers, Ltd., ISBN 978-1-4051-2183-5

- Meijer, J. W. (Trans.) (1990), Jaarboeken: Ab excessu divi Augusti Annales, Ambo, ISBN 978-90-263-1065-2

- Miller, John; Woodman, Anthony (2010), Latin Historiography and Poetry in the Early Empire: Generic Interactions, Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-17755-0

- Newcomb, Horace (1997), Encyclopedia of Television, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-203-93734-1

- Perrottet, Tony (2002), Pagan Holiday: On the Trail of Ancient Roman Tourists, Random House Trade Paperbacks, ISBN 0-375-75639-6

- Pettinger, Andrew (2012), The Republic in Danger: Drusus Libo and the Succession of Tiberius, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-960174-5

- Possanza, D. Mark (2004), Translating the Heavens: Aratus, Germanicus, and the Poetics of Latin Translation, translated by Peter Lang, Classical Studies, ISBN 0-8204-6939-4

- Radman-Livaja, I.; Dizda, M. (2010), "Archaeological Traces of the Pannonian Revolt 6–9 AD:Evidence and Conjectures", Veröffentlichungen der Altertumskommiion für Westfalen Landschaftsverband Westfalen-Lippe, Band XVIII, Aschendorff Verlag, pp. 47–58

- Robinson, Michael F.; Monson, Dale E. (1992), "Porpora Nicola (Antonio)", The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, 3, Grove's Dictionaries of Music, ISBN 978-0-93585-992-8

- Rowe, Greg (2002), Princes and Political Cultures: The New Tiberian Senatorial Decress, University of Michigan Press, ISBN 0-472-11230-9

- Salisbury, Joyce E. (2001), Women in the ancient world, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-57607-092-5, retrieved 3 January 2012

- Shotter, David (1992), Tiberius Caesar, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-203-62502-6

- Simpson, Ch. J. (1981), "The Early Name of the Emperor Claudius", Acta antiqua Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae (29)

- Swan, Michael Peter (2004), The Augustan Succession: An Historical Commentary on Cassius Dio's Roman History, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-516774-0

- Vahimagi, Tise; Grade, Michael Ian (1996), British television: an illustrated guide, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-815926-1

- Ward, Allen M.; Heichelheim, Fritz M.; Yeo, Cedric A. (2010), A History of the Roman People (5th ed.), Prentice Hall, ISBN 978-0205846795

- Wells, Peter S. (2003), The Battle That Stopped Rome, Norton, ISBN 978-0-393-32643-7

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1880). "Germanicus". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. 2. pp. 257–262.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1880). "Germanicus". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. 2. pp. 257–262.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Germanicus. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Germanicus Caesar. |

- Works by or about Germanicus in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Life of Caligula by Suetonius (Loeb Classical Library translation) Much of Caligula's biography focuses on his famous father.

- Life of Caligula by Suetonius (Alexander Thomson translation)

-

"Germanicus Cæsar". The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

"Germanicus Cæsar". The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Manius Aemilius Lepidus and Titus Statilius Taurus |

Consul of the Roman Empire together with Gaius Fonteius Capito 12 |

Succeeded by Gaius Silius and Lucius Munatius Plancus |

| Preceded by Lucius Pomponius Flaccus and Gaius Caelius Rufus |

Consul of the Roman Empire together with Tiberius 18 |

Succeeded by Marcus Junius Silanus Torquatus and Lucius Norbanus Balbus |