German Empire (1848/1849)

| German Empire | ||||||||||

| Deutsches Reich | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

.svg.png) Flag

.svg.png) Imperial Coat of arms

| ||||||||||

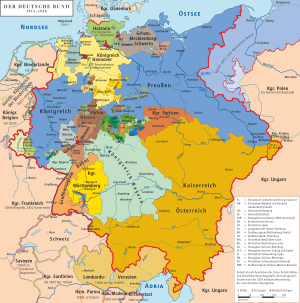

The German Empire in 1849, consisting of the area of the German Confederation. | ||||||||||

| Capital | Frankfurt | |||||||||

| Government | Hereditary Monarchy | |||||||||

| Emperor | ||||||||||

| • | 1849 | Frederick William IV1 | ||||||||

| Imperial Vicar | ||||||||||

| • | 1849 | Archduke John[1] | ||||||||

| Legislature | Frankfurt National Assembly | |||||||||

| History | ||||||||||

| • | Revolution of 1848 | 1848 | ||||||||

| • | Frankfurt National Assembly dissolved | 31 May 1849 | ||||||||

| • | German Confederation restored | 1850 | ||||||||

| ||||||||||

| 1: Frederick William IV was offered the imperial crown, but refused to "pick up a crown from the gutter".[2] | ||||||||||

The German Empire (German: Deutsches Reich) was a short-lived nation state which existed from 1848 to 1849. It was created by the Frankfurt Parliament in spring 1848, following the March Revolution. The empire officially ended when the German Confederation was fully reconstituted in the Summer of 1851, but came to a de facto end in December 1849 when the Central German Government was replaced with a Federal Central Commission.

The Empire struggled to be recognized by both German and foreign states. The German states, represented by the Federal Convention of the German Confederation, on July 12, 1848, acknowledged the Central German Government. In the following months, however, the larger German states did not always accept the decrees and laws of the Central German Government and the Frankfurt Parliament.

Several foreign states recognized the Central Government and sent ambassadors: the United States, Sweden, the Netherlands, Belgium, Switzerland, Sardinia, Sicily and Greece.[3] France and Great Britain installed official envoys to keep contact with the Central Government.

The first constitutional order of the German Empire was the Imperial Law concerning the introduction of a provisional Central Power for Germany, on June 28, 1848. With the order, the Frankfurt Parliament established the offices of Reichsverweser (Imperial Regent, a provisional monarch) and imperial ministers. A second constitutional order, the Frankfurt Constitution, on March 28, 1849, was accepted by 28 German states but not by the larger ones. Prussia, along with other German states, forced the Frankfurt Parliament into dissolution.

Several of this German Empire's accomplishments outlasted it: the Frankfurt Constitution was used as a model in other states in the decades to follow and the electoral law was used nearly verbatim in 1867 for the election of the Reichstag of the North German Confederation. The Reichsflotte (Imperial Fleet) created by the Frankfurt Parliament was lasted until 1852. The imperial law issuing a decree concerning bills of exchange (Allgemeine Deutsche Wechselordnungen, General German exchange bills) was considered to be valid for nearly all of Germany.

Continuity and status

Contemporaries and scholars had different opinions about the statehood of the German Empire of 1848/1849:

- One group followed a positivist point of view: law was statutory law. A constitution for Germany had to be agreed upon with the governments of all German states. This was the opinion of the monarchists and the German states.

- The other group valued natural law and the principle of the sovereignty of the people higher; the National Assembly alone had the power to establish a constitution. This was the opinion of the majority of the Frankfurt Parliament, but especially the republican left.[4]

In reality the distinction was less clear. The majority of the Frankfurt Parliament, based on the liberal groups, wanted to establish a duelist system with a sovereign monarch whose powers would be constrained by a constitution and parliament.

A German Confederation was created in 1815. This treaty organization for the defense of the German territories lacked, in the view of the national movement, a government and a parliament. But it was generally acknowledged by German and foreign powers – to establish a national state, it was the easiest to present it as the continuation of the Confederation. This was actually the road the National Assembly took, although it originally saw itself as a revolutionary organ.

The continuity between the old Confederation and the new organs was based on two decisions of the Confederation's Federal Convention:

- The Federal Convention (representing the German states' governments) called for elections of the Frankfurt Parliament in April/May 1848.

- The German states immediately acknowledged Archduke John, the provisional monarch elected by the Frankfurt Parliament. On July 12, 1848, the Federal Convention ended its activities in favor of the Imperial Regent, Archduke John. This was an implicit recognition of the Law concerning the Central Power of June 28.[5]

Of course, the German states and the Federal Convention made those decisions under pressure of the revolution. They wanted to avoid a breakup with the Frankfurt Parliament. (Already in August this pressure faltered, and the larger states started to regain power.) According to historian Ernst Rudolf Huber, it was possible to determine a continuity or even legal identity of Confederation and the new Federal State. The old institution was enhanced with a (provisional) constitutional order and the name German Confederation was changed to German Empire.[6] Ulrich Huber notes that none of the German states declared the Imperial Regent John and his government to be usurpatory or illegal.[7]

State power, territory and people

The Frankfurt Assembly saw itself as the German national legislature, as made explicit in the Imperial Law concerning the declaration of the imperial laws and the decrees of the provisional Central Power, from September 27, 1848.[8] It issued laws earlier, such as the law of June 14 that created the Imperial Fleet. Maybe the most notable law declared the highly acclaimed Basic Rights of the German People, December 27, 1848.[9]

The Central Power or Central Government consisted of the Imperial Regent, Archduke John, and the ministers he appointed. He usually appointed those politicians that had the support of the Frankfurt Parliament, at least until May 1849. One of the ministers, the Prussian general Eduard von Peucker, was charged with the federal troops and federal fortifications of the German Confederation. The Central Government had not much to govern, as the administration remained in the hands of the single states. But in February 1849, 105 people worked for the Central Government (in comparison to the 10 for the Federal Convention).[10]

The Frankfurt Parliament assumed in general that the territory of the German Confederation was also the territory of the new state. Someone was a German if he was a subject of one of the German states within the German Empire (§ 131, Frankfurt Constitution). Additionally it discussed the future of other territories where Germans lived. The members of parliament sometimes referred to the German language spoken in a territory, sometimes to historical rights, sometimes to military considerations (e.g. when a Polish state was rejected because it would be too weak to serve as a buffer state against Russia). One of the most disputed territories was Sleswig.

Further reading

- Ralf Heikaus: Die ersten Monate der provisorischen Zentralgewalt für Deutschland (Juli bis Dezember 1848). PhD thesis. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main [u. a.] 1997, ISBN 3-631-31389-6

References

- ↑ elected by the Frankfurt National Assembly as Imperial Vicar of a new German Reich. The German Confederation was considered dissolved.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica Vol. 2 p. 1078.

- ↑ Ernst Rudolf Huber: Deutsche Verfassungsgeschichte seit 1789. Band II: Der Kampf um Einheit und Freiheit 1830 bis 1850. 3rd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [et. al.] 1988, p. 638.

- ↑ Simon Kempny: Die Staatsfinanzierung nach der Paulskirchenverfassung. Untersuchung des Finanz- und Steuerverfassungsrechts der Verfassung des deutschen Reiches vom 28. März 1849 (Diss. Münster), Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2011, p. 23.

- ↑ Ralf Heikaus: Die ersten Monate der provisorischen Zentralgewalt für Deutschland (Juli bis Dezember 1848). Diss. Frankfurt am Main, Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main [et. al.], 1997, p. 40/41.

- ↑ Ernst Rudolf Huber: Deutsche Verfassungsgeschichte seit 1789. Band II: Der Kampf um Einheit und Freiheit 1830 bis 1850. 3rd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [et. al.] 1988, p. 634.

- ↑ Ulrich Huber: Das Reichsgesetz über die Einführung einer allgemeinen Wechselordnung für Deutschland vom 26. November 1848. In: JuristenZeitung. 33rd year, no. 23/24 (December 8, 1978), p. 790.

- ↑ Ralf Heikaus: Die ersten Monate der provisorischen Zentralgewalt für Deutschland (Juli bis Dezember 1848). Diss. Frankfurt am Main, Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main [et. al.], 1997, p. 127-129, also footnote 288.

- ↑ Jörg-Detlef Kühne: Die Reichsverfassung der Paulskirche. Vorbild und Verwirklichung im späteren deutschen Rechtsleben. Habil. Bonn 1983, 2rd edition, Luchterhand, Neuwied 1998 (1985), p. 380/381, 526; Dietmar Willoweit: Deutsche Verfassungsgeschichte. Vom Frankenreich bis zur Wiedervereinigung Deutschlands. 5th edition, C.H. Beck, München 2005, p. 304.

- ↑ Hans J. Schenk: Ansätze zu einer Verwaltung des Deutschen Bundes. In: Kurt G. A. Jeserich (ed.): Deutsche Verwaltungsgeschichte. Band 2: Vom Reichsdeputationshauptschluß bis zur Auflösung des Deutschen Bundes. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1983, p. 155–165, here p. 164.