Georgy Zhukov

| Georgy Zhukov | |

|---|---|

| Гео́ргий Жу́ков | |

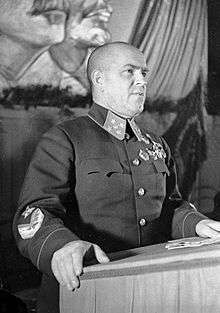

Zhukov in 1944 | |

| Minister of Defence | |

|

In office 9 February 1955 – 26 October 1957 | |

| Premier | Nikolai Bulganin |

| Preceded by | Nikolai Bulganin |

| Succeeded by | Rodion Malinovsky |

| Full member of the 20th Politburo | |

|

In office 29 June – 29 October 1957 | |

| Candidate member of the 20th Politburo | |

|

In office 27 February 1956 – 29 June 1957 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Georgy Konstantinovich Zhukov (Гео́ргий Константи́нович Жу́ков) 1 December 1896 Strelkovka, Kaluga Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died |

18 June 1974 (aged 77) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Nationality |

|

| Political party | Communist Party of the Soviet Union |

| Spouse(s) |

Alexandra Dievna Zuikova (1920–1953) Galina Alexandrovna Semyonova (1965–1974) |

| Children |

Era Zhukova (born 1928) |

| Profession | Soldier |

| Awards |

|

| Signature |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

Russian Imperial Army Soviet Army |

| Years of service | 1915–1957 |

| Rank | Marshal of the Soviet Union |

| Commands |

Kiev Military District Chief of the General Staff Reserve Front Leningrad Front Western Front 1st Belorussian Front Odessa Military District |

| Battles/wars |

World War I Russian Civil War Soviet–Japanese Border War (Battles of Khalkhin Gol) Soviet occupation of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina Great Patriotic War |

Georgy Konstantinovich Zhukov (Russian: Гео́ргий Константи́нович Жу́ков; IPA: [ɡʲɪˈorgʲɪj kənstɐnˈtʲinəvʲɪtɕ ˈʐukəf]; 1 December [O.S. 19 November] 1896 – 18 June 1974), was a Soviet-Russian officer in the Red Army of the Soviet Union who became Chief of General Staff, Deputy Commander-in-Chief, Minister of Defence and a member of the Politburo. During World War II he participated in multiple battles, ultimately commanding the 1st Belorussian Front in the Battle of Berlin, which resulted in the defeat of Nazi Germany, and the end of the War in Europe

In recognition of Zhukov's role in World War II, he was allowed to participate in signing the German Instrument of Surrender and to inspect the Moscow Victory Parade of 1945.

Early life and career

Born into a poverty-stricken peasant family in Strelkovka, Maloyaroslavsky Uyezd, Kaluga Governorate (now merged into the town of Zhukov in Zhukovsky District of Kaluga Oblast in modern-day Russia), Zhukov became an apprentice furrier in Moscow. In 1915 the Army of the Russian Empire conscripted him; he served first in the 106th Reserve Cavalry Regiment (then called the 10th Dragoon Novgorod Regiment).[1][2] During World War I, Zhukov was awarded the Cross of St. George twice, and promoted to the rank of non-commissioned officer for his bravery in battle. He joined the Bolshevik Party after the 1917 October Revolution; in Party circles his background of poverty became a significant asset. After recovering from a serious case of typhus he fought in the Russian Civil War over the period 1918 to 1921, serving with the 1st Cavalry Army, among other formations. He received the decoration of the Order of the Red Banner for his part in subduing the Tambov Rebellion in 1921.[3]

Early peacetime service

At the end of May 1923, Zhukov became a commander of the 39th Cavalry Regiment.[4] In 1924, he entered the Higher School of Cavalry,[5] from which he graduated the next year, returning afterward to command the same regiment.[6] In May 1930, Zhukov became commander of the 2nd Cavalry Brigade of the 7th Cavalry Division.[7] In February 1931, he was appointed the Assistant Inspector of Cavalry of the Red Army.[8] In May 1933, Zhukov was appointed a commander in the 4th Cavalry Division.[8] In 1937, he became a commander of the 3rd Cavalry Corps, later of the 6th Cavalry Corps.[8][9] In 1938, he became a deputy commander of the Belorussian Military District for cavalry.[8][10]

Khalkhin Gol to Barbarossa

In 1938, Zhukov was directed to command the First Soviet Mongolian Army Group, and saw action against Japan's Kwantung Army on the border between Mongolia and the Japanese-controlled state of Manchukuo. This campaign was an undeclared war that lasted from 1938 to 1939. What began as a routine border skirmish rapidly escalated into a full-scale war, with the Japanese pushing forward with an estimated 80,000 troops, 180 tanks and 450 aircraft.

These events led to the strategically decisive Battle of Khalkhin Gol (Nomonhan). Zhukov requested major reinforcements, and on 20 August 1939, his "Soviet Offensive" commenced. After a massive artillery barrage, nearly 500[11] BT-5 and BT-7 tanks advanced, supported by over 500[12] fighters and bombers. This was the Soviet Air Force's first fighter-bomber operation.[13] The offensive first appeared to be a typical conventional frontal attack. However, two tank brigades were initially held back and then ordered to advance around on both flanks, supported by motorized artillery, infantry, and other tanks. This daring and successful manoeuvre encircled the Japanese 6th Army and captured the enemy's vulnerable rear supply areas. By 31 August 1939, the Japanese had been cleared from the disputed border, leaving the Soviets clearly victorious.[13]

This campaign had significance beyond the immediate tactical and local outcome. Zhukov demonstrated and tested the techniques later used against the Germans in the Eastern Front of the Second World War. These innovations included the deployment of underwater bridges[14] and improving the cohesion and battle-effectiveness of inexperienced units by adding a few experienced, battle-hardened troops to bolster morale and overall training.[15] Evaluation of the problems inherent in the performance of the BT tanks led to the replacement of their fire-prone petrol (gasoline) engines with diesel engines, and provided valuable practical knowledge that was essential to the success in development of the T-34 medium tank, widely considered the most outstanding all-around general purpose tank of World War II. After this campaign, Nomonhan veterans were transferred to units that had not seen action, to better spread the benefits of their battle experience.[14]

For his victory, Zhukov was declared a Hero of the Soviet Union. However, the campaign – and especially Zhukov's pioneering use of tanks – remained little known outside of the Soviet Union itself. Zhukov considered Nomonhan invaluable preparation for conducting operations during the Second World War.[16]

In 1940 Zhukov became an Army General.

Pre-war military exercises

In autumn 1940, G. K. Zhukov started preparing the plans for the military exercise concerning the defence of the Western border of the Soviet Union, which at this time was pushed further to the west due to the annexation of Eastern Poland.[17]

In his memoirs Zhukov reports that in this exercise he commanded the "Western" or "Blue" forces (the supposed invasion troops) and his opponent was Colonel General D. G. Pavlov, the commander of the "Eastern" or "Red" forces (the supposed Soviet troops). He noted that the "Blue" had 60 divisions, while the "Red" had 50 divisions. Zhukov in his memoirs describes the events of exercise as similar to actual events during the German invasion.[18]

As historian Bobylev reports in his article in "Military History Journal", the actual details of the exercises were reported differently in different memoirs of their participants.[19] He reported that there were two exercises, one on 2–6 January 1941 (for the North-West direction), another on 8–11 January 1941 (for the South-West direction).[19] In the first one "Western" forces attacked "Eastern" forces on 15 July, but "Eastern" forces counterattacked and by 1 August reached the original border.[19]

At that time (start of the exercise), "Eastern" forces had a numerical advantage (for example, 51 infantry division against 41, 8811 tanks against 3512), with the exception of anti-tank guns.[19] Bolylev describes how by the end of the exercise the "Eastern" forces did not manage to surround and destroy the "Western" forces, which, in their turn, threatened to surround the "Eastern" forces themselves.[19] The same historian reported that the second game was won by the "Easterners", meaning that on the whole, both games were won by the side commanded by Zhukov.[19] However, he noted that the games had a serious disadvantage since they did not consider the initial attack by "Western" forces, but only a (later) attack by "Eastern" forces from the initial border.[19]

According to Marshal Aleksandr Vasilevsky, the war-game defeat of Pavlov's Red Troops against Zhukov was not known widely, but the victory of Zhukov's Red Troops against Kulik was widely propagandized, which created a popular illusion of easy success for a preemptive offensive.[20]

On 1 February 1941, Zhukov became chief of the Red Army's General Staff.[21]

Controversy about a plan for war with Germany

From 2 February 1941, as the Chief of the General Staff, and Deputy Minister of Defense of the USSR, Zhukov took part in drawing up the "Strategic plan for deployment of the forces of the Soviet Union in the event of war with Germany and its allies."[22] The plan was completed no later than 15 May 1941.

Some researchers (for example, Victor Suvorov) conclude that, on 14 May, Soviet People's Commissar of Defense Semyon Timoshenko and Zhukov suggested to Joseph Stalin a preemptive attack against Germany through Southern Poland. Soviet forces would occupy the Vistula Border and continue to Katowice or even Berlin (should the main German armies retreat), or the Baltic coast (should German forces not retreat and be forced to protect Poland and East Prussia). The attacking Soviets were supposed to reach Siedlce, Deblin, and then capture Warsaw before penetrating toward the southwest and imposing final defeat at Lublin.[23]

Historians do not have the original documents that could verify the existence of such a plan, or whether Stalin accepted it. In a transcript of an interview on 26 May 1965, Zhukov stated that Stalin did not approve the plan. However, Zhukov did not clarify whether execution was attempted. As of 1999, no other approved plan for a Soviet attack had been found.[24]

Eastern front of World War II

On 22 June 1941, Germany launched Operation Barbarossa, an invasion of the Soviet Union. On the same day, Zhukov responded by signing the "Directive of Peoples' Commissariat of Defence No. 3", which ordered an all-out counteroffensive by Red Army forces: he commanded the troops "to encircle and destroy [the] enemy grouping near Suwałki and to seize the Suwałki region by the evening of 24 June" and "to encircle and destroy the enemy grouping invading in [the] Vladimir-Volynia and Brody direction" and even "to seize the Lublin region by the evening of 24 June".[25] Despite numerical superiority, this manoeuvre failed, disorganized Red Army units were destroyed by the Wehrmacht. Zhukov subsequently claimed that he was forced to sign the document by Joseph Stalin, despite the reservations that he raised.[26] This document was supposedly written by Aleksandr Vasilevsky.[27]

On 29 July 1941 Zhukov was removed from his post of Chief of the General Staff. In his memoirs he gives his suggested abandoning of Kiev to avoid an encirclement as a reason for it.[28] On the next day the decision was made official and he was appointed the commander of the Reserve Front.[28] There he oversaw the Yelnya Offensive.

On 10 September 1941 Zhukov was made the commander of the Leningrad Front.[29] There he oversaw the defence of the city.

On 6 October 1941 Zhukov was appointed the representative of Stavka for the Reserve and Western Fronts.[30] On 10 October 1941 those fronts were merged into the Western Front under Zhukov's command.[31] This front then participated in the Battle of Moscow and several Battles of Rzhev.

In late August 1942 Zhukov was made Deputy Commander-in-Chief and sent to the southwestern front to take charge of the defence of Stalingrad.[32] He and Vasilevsky later planned the Stalingrad counteroffensive.[33] In November Zhukov was sent to coordinate the Western Front and the Kalinin Front during Operation Mars.

In January 1943 he (together with Kliment Voroshilov), coordinated the actions of the Leningrad and Volkhov Fronts and the Baltic Fleet in Operation Iskra.[34]

Zhukov was a Stavka coordinator at the Battle of Kursk in July 1943. According to his memoirs, he played a central role in the planning of the battle and the hugely successful offensive that followed. Commander of the Central Front Konstantin Rokossovsky, said, however, that the planning and decisions for the Battle of Kursk were made without Zhukov, that he only arrived just before the battle, made no decisions and left soon afterwards, and that Zhukov exaggerated his role.[35]

From 12 February 1944 Zhukov coordinated the actions of the 1st Ukrainian and 2nd Ukrainian Fronts.[36] On 1 March 1944 Zhukov was appointed the commander of the 1st Ukrainian Front[37] until early May.[38] During the Soviet offensive Operation Bagration, Zhukov coordinated the 1st Belorussian and 2nd Belorussian Fronts, later the 1st Ukrainian Front as well.[39] On 23 August Zhukov was sent to the 3rd Ukrainian Front to prepare for the advance into Bulgaria.[40]

On 16 November he became commander of the 1st Belorussian Front[41] which took part in the Vistula–Oder Offensive and the battle for Berlin. He called on his troops to "remember our brothers and sisters, our mothers and fathers, our wives and children tortured to death by [the] Germans...We shall exact a brutal revenge for everything." In a reprise of similar atrocities committed by German soldiers against Russian civilians in the eastward advance into Soviet territory during Operation Barbarossa, the westward march by Soviet forces was marked by brutality towards German civilians, which included looting, burning and rape.[42]

Zhukov was present when German officials signed the Instrument of Surrender in Berlin.[43]

Post-war service under Stalin

After the German capitulation, Zhukov became the first commander of the Soviet Occupation Zone in Germany. On 10 June, Zhukov returned to Moscow to prepare for the Moscow Victory Parade of 1945 in Red Square. On 24 June, Stalin appointed him Commander-in-Chief of the Parade. After the Victory Ceremony, on the night of 24 June, Zhukov went to Berlin to resume his command.[44]

During May 1945, Zhukov signed three resolutions regarding the maintenance of an adequate standard of living for the German people living in the Soviet occupation zone:

- Resolution 063 (11 May 1945): dealt with the provision of food for the people living in Berlin

- Resolution 064 (12 May 1945): allowed for the restoration and maintenance of the normal activities of the public service sector of Berlin

- Resolution 080 (31 May 1945): dealt with providing milk supplies for the children living in Berlin.

Zhukov requested the Soviet Government to transport urgently to Berlin 96,000 tons of grain, 60,000 tons of potatoes, 50,000 cattle, and thousands of tons of other foodstuffs, such as sugar and animal fat. He issued strict orders that his subordinates were to "Hate Nazism but respect the German people", and to make all possible efforts to restore and maintain a stable living standard for the German population.[45]

From 16 July to 2 August, Zhukov participated in the Potsdam Conference with the other Allied governments. As one of the four commanders-in-chief of Allied forces in Germany, Zhukov established good relationships with the other commanders-in-chief, General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower (US), Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery (UK) and Marshal Jean de Lattre de Tassigny (France). These four generals exchanged views about matters such as judging war criminals, rebuilding Germany, relationships between the Allies and defeating the Japanese Empire. Eisenhower seemed to be especially satisfied with, and respectful of, his relationship with Zhukov. Eisenhower's successor, General Lucius Clay, also praised the Zhukov-Eisenhower friendship, and commented:

The Soviet-America relationship should have developed well if Eisenhower and Zhukov had continued to work together.— Lucius Dubignon Clay.[46]

Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied commander in the West, was a great admirer of Zhukov,[47] and the two toured the Soviet Union together in the immediate aftermath of the victory over Germany.[48]

Zhukov was not only the supreme Military Commander of the Soviet Occupation Zone in Germany, but became its Military Governor on 10 June 1945. A war hero, hugely popular with the military, Zhukov was viewed by Stalin as a potential threat to his leadership. He replaced Zhukov with Vasily Sokolovsky on 10 April 1946. After an unpleasant session of the Main Military Council—in which Zhukov was bitterly attacked and accused of political unreliability and hostility to the Party Central Committee—he was stripped of his position as Commander-in-Chief of the Soviet Ground Forces.[49] He was assigned command of the Odessa Military District, far from Moscow and lacking in strategic significance and troops. He arrived there on 13 June.

Zhukov suffered a heart attack in January 1948, spending a month in hospital. In February 1948, he was given another secondary posting, this time command of the Urals Military District.

Throughout this time, Lavrentiy Beria was apparently trying to topple Zhukov. Two of Zhukov's subordinates, Marshal of the Red Air Force Alexander Alexandrovich Novikov and Lieutenant-General Konstantin Fyodorovitch Telegin (Member of the Military Council of 1st Belorussia Army Group) were arrested and tortured in Lefortovo Prison at the end of 1945. In a conference, all generals except Director of the Main Intelligence Directorate Filipp Ivanovich Golikov defended Zhukov against accusation of misspending of war booty and exaggeration of Nazi Germany's strength. During this time, Zhukov was accused of being a Bonapartist.[50]

In 1946, seven rail carriages with furniture that Zhukov was taking to the Soviet Union from Germany were impounded. In 1948, his apartments and house in Moscow were searched and many valuables looted from Germany were found.[51] In his investigation Beria concluded that Zhukov had in his possessions 17 golden rings, three gemstones, the faces of 15 golden necklaces, more than 4,000 meters of cloth, 323 pieces of fur, 44 carpets taken from German palaces, 55 paintings and 20 guns".[52] Zhukov admitted in a memorandum to Zhdanov:

I felt very guilty. I shouldn't have collected those useless junks and put them into some warehouse, assuming nobody needs them any more. I swear as a Bolshevik that I would avoid such errors and follies thereafter. Surely I still and will wholeheartly serve the Motherland, the Party, and the Great Comrade Stalin."[53]

These incidents were ironically called the "Trophy Affair" in the Soviet Union.

When learning of Zhukov's "misfortunes" — and despite not understanding all the problems — Eisenhower expressed his sympathy for his "comrade-in-arms" (Zhukov).[54]

On February 1953, Stalin ordered Zhukov to leave the post of commander of the Urals Military District, and then recalled him to Moscow. Several opinions suggested Zhukov was needed for Korean War service; but, in fact, during one month at Moscow, Stalin did not give Zhukov any tasks. At 9:50 a.m. on 5 March 1953, Stalin suddenly died. After this event, Zhukov's life entered a new phase.[46]

Reasons for Zhukov's rises and falls under Stalin

During the Great Patriotic War, Zhukov was one of only a few people who understood Stalin's personality. As the Chief of Staff and later Deputy Supreme Commander, Zhukov had hundreds of meetings with Stalin, both private and during Stavka conferences. Consequently, Zhukov well understood Stalin's personality and methods. According to Zhukov, Stalin was a strong and secretive person, but he was also hot-tempered and skeptical. Zhukov was able to gauge Stalin's mood; for example, when Stalin drew deeply on his tobacco pipe, it was a sign of a good mood. Conversely, if Stalin failed to light his pipe once it was out of tobacco, it was a sign of an imminent rage.[55] An outstanding knowledge of Stalin's personality was very helpful to Zhukov, and it assisted him to deal with Stalin's rages in a way other Soviet generals could not.[56] Both Zhukov and Stalin were hot-tempered, but, at different times, each of them made concessions in order to sustain their relationship.

While Zhukov simply viewed his relationship with Stalin as one of subordinate–senior, Stalin was in awe and possibly jealous of Zhukov. Both were military commanders, but Stalin's experience was restricted to a previous generation of non-mechanized warfare. By contrast, Zhukov was highly influential in the development of contemporary combined operations of highly mechanized armies. The differences in these outlooks were responsible for many tempestuous disagreements between the two of them at Soviet Stavka meetings. Nonetheless, Zhukov was less competent than Stalin as a politician, an inadequacy which accounted for Zhukov's many failures in Soviet politics. In fact, Stalin's unwillingness to value Zhukov beyond the marshal's military talents was one of the reasons why Stalin recalled Zhukov from Berlin.[2]

Another significant element of their relationship was Zhukov's straightforwardness toward Stalin. Stalin was dismissive of the fawning of many of his entourage and openly criticised it.[57] Many people around Stalin — such as Beria, Yezhov, Mekhlis, and some others — felt the need to flatter Stalin to remain on his good side.[58] Zhukov was different. By contrast, he was stubbornly willing to express his views, often going openly against Stalin's opinion even to the point of risking his career and life. His heated argument with Stalin on the subject of abandoning Kiev in June 1941 was a typical example of Zhukov's approach.[59] This independence in Zhukov's thinking gained Stalin's respect. It caused Zhukov considerable difficulties with Stalin on several occasions, but was the main reason the decision-making of Stavka became more objective and effective.

After the war, things were less successful for Zhukov, and his independent-mindedness caused him many problems. Indeed, under the personality cult of the Stalinist regime and its overweening bureaucracy and emphasis on conformity, there was little place within the government for people like Zhukov.[60]

Rise and fall after Stalin

After Stalin's death, Zhukov returned to favor, becoming Deputy Defense Minister in 1953. He then had an opportunity to avenge himself on Beria.

Arresting Beria

With Stalin's sudden death, the Soviet Union fell into a leadership crisis. Georgy Maximilianovich Malenkov temporarily became First Secretary. Malenkov and his allies attempted to purge Stalin's influence and personality cult; however, Malenkov himself did not have the courage to do this alone. Moreover, Lavrentiy Beria remained dangerous. The politicians sought reinforcement from the powerful and prestigious military men. In this matter, Nikita Khrushchev chose Zhukov because the two had forged a good relationship, and, in addition, in the Great Patriotic War, Zhukov had twice saved Khrushchev from false accusations.[61][62]

On 26 June 1953, a special meeting of the Soviet Politburo was held by Malenkov. Beria came to the meeting with an uneasy feeling because it was called hastily—indeed, Zhukov had ordered General Kirill Moskalenko to secretly prepare a special force and permitted the force to use two of Zhukov's and Bulganin's special cars (which had black glass) in order to safely infiltrate the Kremlin. Zhukov also ordered him to replace the MVD Guard with the guard of the Moscow Military District. In this meeting, Khrushchev, Malenkov and their allies denounced "the imperialist element Beria" for his "anti-Party", "anti-socialist" activities, "sowing division", and "acting as a spy of England", together with many other crimes. Finally, Khrushchev suggested expelling Beria from the Communist Party and bringing him before a military court. Immediately, the prepared special force rushed in. Zhukov himself went up to Beria and shouted: "Hands up! Follow me!". Beria replied, in a panic, "Oh Comrades, what's the matter? Just sit down." Zhukov shouted again, "Shut up, you are not the commander here! Comrades, arrest this traitor!". Moskalenko's special forces obeyed.[63][64]

Marshal Zhukov was a member of the military tribunal during the Beria trial, which was headed by Marshal Ivan Konev.[65] On 18 December 1953, the Military Court sentenced Beria to death. During the burial of Beria, Konev commented: "The day this man was born deserves to be damned!". Then Zhukov said: "I considered it as my duty to contribute my little part in this matter (arresting and executing Beria)."[63][64]

Minister of Defense and Politburo candidate membership

When Nikolai Bulganin became premier in 1955, he appointed Zhukov Defense Minister.[65] Zhukov participated in many political activities. He successfully opposed the re-establishment of the Commissar system, because the Party and political leaders were not professional military, and thus the highest power should fall to the army commanders. Until 1955, Zhukov had both sent and received letters from Eisenhower. Both leaders agreed that the two superpowers should coexist peacefully.[66] In July 1955, Zhukov—together with Khrushchev, Bulganin, V. M. Molotov and A. A. Gromyko—participated in a Summit Conference at Geneva after the USSR signed a peace treaty with Austria and withdrew its army from that country.

Zhukov followed orders from the then Prime Minister Georgy Malenkov and Communist Party leader Khrushchev during the invasion of Hungary following the 1956 Hungarian Revolution.[67] Along with the majority of members of the Presidium, he urged Khrushchev to send troops to support the Hungarian authorities and to secure the Austrian border. Zhukov and most of the Presidium were not, however, eager to see a full-scale intervention in Hungary. Zhukov even recommended the withdrawal of Soviet troops when it seemed that they might have to take extreme measures to suppress the revolution. The mood in the Presidium changed again when Hungary's new Prime Minister, Imre Nagy, began to talk about Hungarian withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact. That led the Soviets to attack the revolutionaries and to replace Nagy with János Kádár. In the same years, when the UK, France and Israel invaded Egypt during the Suez crisis, Zhukov expressed support for Egypt's right of self-defense. In October 1957, Zhukov visited Yugoslavia and Albania aboard the Chapayev-class cruiser Kuibyshev, attempting to repair the Tito–Stalin split of 1948.[68] During the voyage, Kuibyshev encountered units of the United States Sixth Fleet—"passing honors" were exchanged between the vessels.

Defeating the "Anti-Party Group" and subsequent fall from power

On his 60th birthday (in 1956), Zhukov received his fourth Hero of the Soviet Union title. He became the highest-ranking military professional who was also a member of the Presidium of the Central Committee of the Communist Party. He further became a symbol of national strength. Zhukov's prestige was even higher than the police and security agencies of the USSR, and thus rekindled concerns among political leaders. For example, going even further than Khrushchev, Zhukov demanded that the political agencies in the Red Army report to him before the Party. He demanded an official condemnation of Stalin's crimes during the Great Purge . He also supported the political vindication and rehabilitation for M. N. Tukhachevsky, V. K. Blyukher, A. I. Yegorov and many others. In response his opponents accused him of being a Reformist and Bonapartist. Such enviousness and hostility proved to be the key factor that led to his later downfall.[69]

The relationship between Zhukov and Khrushchev reached its peak during the XX Congress of the Communist Party (1956). After becoming the First Secretary of the Party, Khrushchev moved against Stalin's legacy and criticized his "personality cult". To complete such startling acts, Khrushchev needed the approval—or at least the acquiescence—of the military, headed by Minister of Defense Zhukov.

At the plenary session of Central Committee of CPSU held in June 1957 Zhukov supported Khrushchev against the "Anti-Party Group", that had a majority in the Presidium and voted to replace Khrushchev as First Secretary with Bulganin. At that plenum, Zhukov stated:

The Army is against this resolution and not even a tank will leave its position without my order!— G. K. Zhukov[70]

In the same session the "Anti-Party Group" was condemned and Zhukov was made a member of Presidium. But, in that same year, he was removed from the Presidium of the Party's Central Committee and the Ministry of Defense, entering forced retirement at age 62. These things happened behind his back, when he was on a trip to Albania at the invitation of Gen. Col. Beqir Balluku.[71] Interestingly, the same issue of Krasnaya Zvezda (Red Star) that announced Zhukov's return also reported that he had been relieved of his duties.[72] According to many researchers, Soviet politicians (including Khrushchev himself) had a deep-seated fear of "powerful people."[73][74]

Retirement

After being forced out of the government, Zhukov stayed away from politics. Many people—including former subordinates—frequently paid him visits, joined him on hunting excursions, and waxed nostalgic. In September 1959, while visiting the United States, Khrushchev told US President Eisenhower that the retired Marshal Zhukov "liked fishing" (Zhukov was a keen aquarist[75]). Eisenhower, in response, sent Zhukov a set of fishing tackle. Zhukov respected this gift so much that he is said to have exclusively used Eisenhower's fishing tackle for the remainder of his life.[76]

After Khrushchev was deposed in October 1964, Brezhnev restored Zhukov to favour (though not to power) in a move to use Zhukov's popularity to strengthen his political position. Zhukov's name was put in the public eye yet again when Brezhnev lionized Zhukov in a speech commemorating the Great Patriotic War. On 9 May 1965, Zhukov was invited to sit on the tribunal of the Lenin Mausoleum and given the honor of reviewing the parade of military forces in Red Square.[77]

Zhukov had begun writing his memoirs "Reminiscences and Reflections" (Воспоминания и размышления) in 1958. He now worked intensively on them, which together with steadily deteriorating health, served to worsen his heart disease. In December 1967, Zhukov had a serious stroke. He was hospitalized until June 1968, and continued to receive medical and rehabilitative treatment at home under the care of his second wife, Galina Semyonova, a former officer in the Medical Corps. His memoirs were published in 1969 and became a best-seller. Within several months of the date of publication of his memoirs, Zhukov had received more than 10,000 letters from readers that offered comments, expressed gratitude, gave advice, or lavished praise. Supposedly, the Communist Party invited Zhukov to participate in the XXIV General Assembly in 1971 but the invitation was rescinded.[78]

On 18 June 1974, Zhukov died after another stroke. Contrary to Zhukov's last will for an Orthodox Christian burial, and despite the requests of the family to the country's top leadership,[79] his body was cremated and his ashes were buried at the Kremlin Wall Necropolis alongside fellow generals and marshals of the Soviet Union and later the Russian Federation. Today a large statue of him has been erected in front of the Kremlin depicting him on a horse.

On the 100th anniversary of Zhukov's birth, a panikhida Orthodox memorial service was conducted at his grave, the first such service in the history of the Kremlin Wall Necropolis.[80]

Family

- Father: Konstantin Artemyevich Zhukov (1851–1921), a shoemaker. Konstantin was an orphan who was adopted by Ms. Anuska Zhukova at the age of two.

- Mother: Ustinina Artemievna Zhukova (1866–1944), a farmer descended from a poor family. According to Zhukov his mother was a person with considerable strength who could carry five put (about 80 kilograms) of wheat on her shoulder. Zhukov thought he had inherited his strength from his mother.

- Elder sister: Maria Kostantinovna Zhukova (born 1894).

- Younger brother: Alexei Konstantinovich Zhukov (born 1901), died prematurely.

- First wife: Alexandra Dievna Zuikova (1900–1967), common-law wife since 1920, married in 1953, divorced in 1965. Died after a stroke.

- Second wife: Galina Alexandrovna Semyonova (1926 – November 1973[81]), Colonel, military officer in the Soviet Medical Corps, worked at Burdenko Hospital, specialized in therapeutics. Married in 1965. Died of breast cancer.

- First daughter: Era Zhukova (born 1928), mothered by Alexandra Dievna Zukova.

- Second daughter Margarita Zhukova (1929–2011), mothered by Maria Nikolaevna Volokhova (1897–1983).

- Third daughter: Ella Zhukova (1937–2010), mothered by Alexandra Dievna Zukova.

- Fourth daughter: Maria Zhukova (born 1957), mothered by Galina Alexandrovna Semyonova.

Controversy and praise

Appraisals of Zhukov's career vary. For example, historian Konstantin Zaleski claimed that Zhukov exaggerated his own role in the Great Patriotic War.[82] Marshal Konstantin Rokossovsky said that the planning and decisions for the Battle of Kursk were made without Zhukov, that he only arrived just before the battle, made no decisions and left soon after.[35] Andrei Mertsalov stated that Zhukov was rude and wayward. Mertsalov further accused Zhukov of setting unnecessarily and terribly strict rules toward his subordinates.[83]

Others note Zhukov's "dictatorial" approach. For example, Major General P. G. Grigorienko stated that Zhukov demanded unconditional compliance with his orders. Some notable examples for these points include the time, on 28 September 1941, that Zhukov sent ciphered telegram No. 4976 to commanders of the Leningrad Front and the Baltic Navy, announcing that returned prisoners and families of soldiers captured by the Germans would be shot.[84] This order was published for the first time in 1991 in the Russian magazine Начало (Beginning) No. 3. In the same month, Zhukov apparently ordered that any soldiers who left their positions would be shot.[85]

Some historians stated that Zhukov was a typical "squander-soldier general" who was unmoved by his forces' loss of life. Others such as A. V. Isaev reject this idea, and quote some of Zhukov's orders stored by the Russian Ministry of Defense and Government of Moscow to prove that Zhukov did care about the lives of his soldiers:

The commanders of the divisions are personally at fault for the 49th Army's failure to accomplish its objectives and for its heavy casualties. They still grossly violate the instructions of Comrade Stalin and the order of the Front regarding the use of massed artillery to achieve a breakthrough, and about the tactics and techniques of attacking the defenses of populated areas. The units of the 49th Army for many days criminally continue their head-on attacks on Kostino, Ostrozhnoye, Bogdanovo and Potapovo without any success, while suffering heavy losses.Even a person with basic military education can understand that these settlements are very suitable defensive positions. The areas in front of these settlements are ideal for firing upon, but despite this the criminally conducted attacks continue in the same places. As a result of the stupidity and indiscipline of the organizers, people pay with their lives, without bringing any benefit to the Motherland.

If you still want to keep your current ranks, I demand:

Immediately stop the criminal head-on attacks on the settlements. Stop the head-on attacks on heights with good firing positions. When attacking make full use of ravines, forests and terrain that is not easily fired upon. Immediately breakthrough between the settlements and, without waiting for their complete fall, tomorrow capture Sloboda, Rassvet and advance up to Levshina.

Report the execution of the order to me by 24:00 of 27 January.

— Order of G. K. Zhukov to the commander of the 49th Army on 27 January 1942.[86]

It is in vain that you think that victory can be achieved by using "people's meat." Victory is achieved through the art of combat. War is waged with skill, not with people's lives.— Order of G. K. Zhukov to I. G. Zakharkin on 7 March 1942.[87]

In the armies of the Western Front, a completely unacceptable attitude towards saving personnel has recently developed. Commanders of formations and units, when conducting battles and sending people to accomplish military tasks, are not responsible enough in saving soldiers and officers. Recently, the Stavka has been sending reinforcements to the Western Front more than any other front by two or three times, but it is unacceptable that this replenishment is quickly lost and the units are again left without enough men, because of the negligent and sometimes criminal attitude of the commanders towards saving the lives and health of people.— Order of G. K. Zhukov on 15 March 1942.[88]

Zhukov also received many positive comments, mostly from his Army companions, from the modern Russian Army, and from his Allied contemporaries. General of the Army Eisenhower stated that, because of Zhukov's achievements fighting the Nazis, the United Nations owed him much more than any other military leader in the world.

The war in Europe ended with victory and nobody could have done that better than Marshal Zhukov – we owed him that credit. He is a modest person, and so we can't undervalue his position in our mind. When we can come back to our Motherland, there must be another type of Order in Russia, an Order named after Zhukov, which is awarded to everybody who can learn the bravery, the far vision, and the decisiveness of this soldier.— Dwight D. Eisenhower[89]

Marshal of the Soviet Union Aleksandr Vasilevsky commented that Zhukov is one of the most outstanding and brilliant military commanders of the Soviet Military Force.[90] Major General Sir Francis de Guingand, Chief of Staff of Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, described Zhukov as a friendly person.[91] US writer John Gunther, who met Zhukov many times after the war, said that Zhukov was more friendly and honest than any other Soviet leaders.[92] John Eisenhower – Dwight Eisenhower's son – claimed that Zhukov was really ebullient and was a friend of his.[66] Albert Axell in his work "Marshal Zhukov, the one who beat Hitler" claimed that Zhukov is a military genius like Alexander the Great and Napoleon. Axell also commented that Zhukov is a loyal communist and a patriot.[93]

At the end of his work about Zhukov, Otto Chaney concluded:

But Zhukov belongs to all of us. In the darkest period of World War II his fortitude and determination eventually triumphed. For Russians and people everywhere he remains an enduring symbol of victory on the battlefield.— Otto Chaney[94]

In September 1954, Zhukov was in charge of the Totskoye nuclear exercise. A 40-kiloton nuclear weapon was tested in an exercise involving 45,000 soldiers. The soldiers who participated in the exercise moved into the area after the blast occurred (following measurement by Gamma-roentgenometers) and were provided with protective suits and masks. Zhukov reported the test as successful, although it was one of the worst environmental disasters in the post-war Soviet Union.[95] There are no official figures of fatalities due to the test. Tamara Zlotnikova, former member of the Russian Duma, believes that thousands may have died from long term effects of radiation, which were not appreciated at that time (other major nuclear powers including the US, France and UK conducted nuclear-bomb tests with human subjects either at a set distance from the epicentre, or who entered the blast site afterwards). [96] Soldiers who participated in the exercise were ordered to sign statements to remain silent about the test.[97]

Awards

Zhukov was a recipient of decorations. Most notably he was awarded the Hero of the Soviet Union four times. Aside from Zhukov, only Leonid Brezhnev was a four-time recipient (the latter's were self-awarded).

Zhukov was one of only three recipients to receive the Order of Victory twice. He was also awarded high honors from many other countries. A partial listing is presented below.

Russian Imperial decorations

| Cross of St. George (3rd and 4th class) | |

Soviet orders and medals

Foreign awards

| Hero of the Mongolian People's Republic (Mongolian People's Republic, 1969) | |

| Medal "30 year anniversary of the Battle of Khalkhin Gol" (Mongolian People's Republic, 1969) | |

| Order of Sukhbaatar (Mongolian People's Republic, 1968, 1969, 1971) | |

| Order of the Red Banner (Mongolian People's Republic, 1939 and 1942) | |

| Medal "50 years of the Mongolian People's Republic" (Mongolian People's Republic, 1971) | |

| Medal "50 years of the Mongolian People's Army" (Mongolian People's Republic, 1971) | |

| Medal "For Victory over Japan" (Mongolian People's Republic) | |

| Order of the White Lion, 1st class (Czechoslovakia, 1945) | |

| Military Order of the White Lion "For Victory", 1st class (Czechoslovakia, 1945) | |

| Czechoslovak War Cross (Czechoslovakia, 1945) | |

| Cross of Grunwald, 1st class (Poland, 1945) | |

| Grand Cross of the Virtuti Militari (Poland, 1945) | |

| Commander's Cross with Star of the Polonia Restituta, (Poland, 1968, and Commander's Cross, 1973) | |

| Medal "For Warsaw 1939–1945" (Poland, 1946) | |

| Medal "For Oder, Neisse and the Baltic" (Poland, 1946) | |

| Chief Commander, Legion of Merit (US, 1945) | |

| Honorary Knight Grand Cross, Order of the Bath, (military division) (UK, 1945) | |

| Grand Cross of the Legion d'Honneur (France, 1945) | |

| Croix de guerre (France) | |

| Medal "Sino-Soviet friendship", (China, 1953 and 1956) | |

| Order of Freedom (SFR Yugoslavia, 1956) | |

| Order of Merit, 1st class (Grand Cross) (Egypt, 1956) | |

| Medal "90th Anniversary of the Birth of Georgiy Dimitrov" (Bulgaria) | |

| Medal "25 Years of the Bulgarian People's Army" (Bulgaria) | |

| Garibaldi Partisan Star (Italy, 1956) | |

| Order of the Republic (Tuvan People's Republic, 1939) | |

- Title of Honorary Italian Partisan (Italy, 1956)

Legacy

Memorials

The first monument to Georgy Zhukov was erected in Mongolia, in memory of the Battle of Khalkin Gol. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, this monument was one of the few that did not suffer from anti-Soviet backlash in former Communist states.

There is a statue of Zhukov on horseback as he appeared at the 1945 victory parade on Manezhnaya Square at the entrance of the Kremlin in Moscow. Zhukov Statue in Moscow

A minor planet, 2132 Zhukov, discovered in 1975 by Soviet astronomer Lyudmila Chernykh, is named in his honor.[98]

In 1996, Russia adopted the Order of Zhukov and the Zhukov Medal to commemorate the 100th anniversary of his birthday.

Recollections

Nobel laureate Joseph Brodsky's poem On the Death of Zhukov ("Na smert' Zhukova", 1974) is regarded by critics as one of the best poems on the war written by an author of the post-war generation.[99] The poem is a stylization of The Bullfinch, Derzhavin's elegy on the death of Generalissimo Suvorov in 1800. Brodsky draws a parallel between the careers of these two famous commanders.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn re-interpreted Zhukov's memoirs in the short story Times of Crisis.

In his book of recollections,[100] Zhukov was critical of the role the Soviet leadership played during the war. The first edition of Vospominaniya i razmyshleniya, was published during the reign of Leonid Brezhnev only on the conditions that criticism of Stalin was removed, and that Zhukov add a (fictional) episode of a visit to Leonid Brezhnev, politruk at the Southern Front, to consult on military strategy.[101]

References

- ↑ Axell

- 1 2 Chaney

- ↑ (in Russian) B. V. Sokolov (2000) В огне революции и гражданской войны, in Неизвестный Жуков: портрет без ретуши в зеркале эпохи, Minsk: Rodiola-plus.

- ↑ Zhukov, pp. 79, 90 (1st part)

- ↑ Zhukov, p. 87 (1st part)

- ↑ Zhukov, p. 89 (1st part)

- ↑ Zhukov, p. 99 (1st part)

- 1 2 3 4 M. A. Gareev (1996) Маршал Жуков. Величие и уникальность полководческого искусства. Ufa

- ↑ Zhukov, p. 151 (1st part)

- ↑ Zhukov, p. 158 (1st part)

- ↑ Coox, p. 579

- ↑ Coox, p. 590

- 1 2 Coox, p. 633

- 1 2 Coox, p. 998

- ↑ Coox, p. 991

- ↑ Coox, p. 996

- ↑ Tài liệu giải mật của Bộ Quốc phòng Nga (RGVA), quyết định giải mật số 37.977. Số đăng ký: 5. Tờ 564

- ↑ G. K. Zhukov. Reminiscences and reflections (Воспоминания и размышления). Vol 1, pp. 224–225.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 П. Н. БОБЫЛЕВ "Репетиция катастрофы" // "Военно-исторический журнал" № 7, 8, 1993 г.

- ↑ Vasilevsky, p. 24

- ↑ Zhukov, p. 205 (1st part).

- ↑ A. M. Vasilevsky (May 1941) "Соображения по плану стратегического развёртывания сил Советского Союза на случай войны с Германией и её союзниками". Archived from the original on 19 December 2007. Retrieved 2012-06-04.. tuad.nsk.ru

- ↑ Viktor Suvorov (2006). Стратегические замыслы Сталина накануне 22 июня 1941 года, in Правда Виктора Суворова: переписывая историю Второй мировой, Moscow: Yauza

- ↑ M. I. Melyukhov (1999) Упущенный шанс Сталина. Советский Союз и борьба за Европу: 1939—1941. Мoscow

- ↑ as cited by Suvorov: http://militera.lib.ru/research/suvorov7/12.html

- ↑ Zhukov, p. 269

- ↑ P.Ya. Mezhiritzky (2002), Reading Marshal Zhukov, Philadelphia: Libas Consulting, chapter 32.

- 1 2 Zhukov, p. 353.

- ↑ Zhukov, p. 382.

- ↑ Zhukov, p. 8 (2nd part).

- ↑ Zhukov, p. 16 (2nd part).

- ↑ Chaney, pp. 212–213

- ↑ Chaney, p. 224

- ↑ Махмут А. Гареев Маршал Жуков. Величие и уникальность полководческого искусства. М.:—Уфа, 1996.

- 1 2 Военно-исторический журнал, 1992 N3 p. 31

- ↑ Zhukov, p. 205 (2nd part).

- ↑ Zhukov, p. 209 (2nd part).

- ↑ Zhukov, p. 217 (2nd part).

- ↑ Zhukov, p. 222 (2nd part).

- ↑ Zhukov, p. 246 (2nd part).

- ↑ Zhukov, p. 259 (2nd part)

- ↑ William I. Hitchcock, The Bitter Road to Freedom: A New History of the Liberation of Europe (2008) pp. 160-161

- ↑ Zhukov, p. 332 (2nd part).

- ↑ Shtemenko, Vol. 1 pp. 566–569

- ↑ Grigori Deborin (1958). Вторая мировая война. Военно-политический очерк, Moscow: Voenizdat, pp. 340–343.

- 1 2 Axell, p. 356

- ↑ "Password Logon Page". ic.galegroup.com. Retrieved 2017-01-09.

- ↑ Chaney, pp. 346–347

- ↑ Spahr, pp. 200–205

- ↑ I. S. Konev (1991) Записки командующего фронтом (Diary of the Front Commander). Voenizdat. Moscow. pp. 594–599. Warheroes.ru. Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- ↑ Boris Vadimovich Sokolov (2000) Неизвестный Жуков: портрет без ретуши в зеркале эпохи. (Unknown Zhukov), Minsk, Rodiola-plyus, ISBN 985-448-036-4.

- ↑ Жуков Георгий Константинович. БИОГРАФИЧЕСКИЙ УКАЗАТЕЛЬ. Hrono.ru. Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- ↑ Военные архивы России. — М., 1993, p. 244.

- ↑ New York Times. 29 July 1955.

- ↑ G. K. Zhukov. Reminiscences and Reflections. Vol. 2, pp. 139, 150.

- ↑ Axell, p. 280

- ↑ Shtemenko, Vol. 2 p. 587

- ↑ Vasilevsky, p. 62

- ↑ A. I. Sethi. Marshal Zhukov: The Great Strategician. New Delhi: 1988, p. 187.

- ↑ Report of Khrushchev at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (in Vietnamese)

- ↑ Vasilevsky, p. 137

- ↑ Sergei Khrushchev (1990). Khrushchev on Khrushchev. An Inside Account of the Man and His Era, Little, Brown & Company, Boston, pp. 243, 272, 317. ISBN 0316491942.

- 1 2 K. S. Moskalenko (1990). The arrest of Beria. Newspaper Московские новости. No. 23.

- 1 2 Afanasiev, p. 141

- 1 2 Associated Press, 9 February 1955, reported in The Albuquerque Journal p. 1.

- 1 2 John Eisenhower (1974). Strictly Personal. New York. 1974. p. 237, ISBN 0385070713.

- ↑ Johanna Granville (2004) The First Domino: International Decision Making During the Hungarian Crisis of 1956, Texas A & M University Press, ISBN 1-58544-298-4

- ↑ Spahr, pp. 235–238

- ↑ Spahr, p. 391

- ↑ Afanasiev, pp. 151–152

- ↑ Chaney, pp. 444–445

- ↑ Krasnaya Zvezda, 27 October 1957, pp. 3–4, quoted in Spahr, p. 238

- ↑ Afanasiev, p. 152

- ↑ Chaney, pp. 453–455

- ↑ Nowak, Eugeniusz (1998). "Erinnerungen an Ornithologen, die ich kannte". J. Ornithol. (in German). 139: 325–348.

- ↑ Korda, M. (2008) Ike: An American Hero

- ↑ Axell, p. 277

- ↑ Spahr, p. 411

- ↑ Маршал Жуков – Воспоминания дочери (Марии)

- ↑ Станислав МИНАКОВ. Жуков как сын церкви (Еженедельник 2000 выпуск № 51 (347) 22—28 декабря 2006 г.) Archived 29 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Tony Le Tissier (1996). Zhukov at the Oder: The Decisive Battle for Berlin. London, p. 258, ISBN 0811736091.

- ↑ Залесский К. А. Империя Сталина. Биографический энциклопедический словарь. Москва, Вече, 2000; Жуков Георгий Константинович. Хронос, биографии (in Russian)

- ↑ Андрей Николаевич Мерцалов. О Жукове. Родина, № 6, 2004. (in Russian)

- ↑ (in Russian) Boris Sokolov (23 February 2001). "Георгий Жуков: народный маршал или маршал-людоед?". Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 2006-05-29. Grain.ru Retrieved on 2002-07-17

- ↑ Пётр Григорьевич. В подполье можно встретить только крыс. «Детинец», Нью-Йорк, 1981. Lib.ru (2002-04-26). Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- ↑ Isaev, pp. 270–271

- ↑ Isaev, p. 282

- ↑ Isaev, p. 281

- ↑ Dwight D. Eisenhower (1948) Crusade in Europe, New York.

- ↑ Vasilevsky, p. 568

- ↑ Sir Francis de Guingand. Generals at War. London. 1972

- ↑ John Gunther. Inside Russia Today. New York. 1958.

- ↑ The general who defeated Hitler. 8 May 2005. BBC Vietnamese (in Vietnamese)

- ↑ Chaney, p. 483

- ↑ Forczyk, Robert (2012). Georgy Zhukov. Osprey Publishing. p. 58. ISBN 9781780960449.

- ↑ Ong, Carah (2012). "Human Nuclear Experiments". Nuclear Age Peace Foundation.

- ↑ Cooke, Stephanie (2009). In Mortal Hands: A Cautionary History of the Nuclear Age. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 165. ISBN 9781608191574.

- ↑ Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (5th ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. p. 173. ISBN 3-540-00238-3.

- ↑ Shlapentokh, Dmitry. The Russian boys and their last poet. The National Interest. 22 June 1996 Retrieved on 2002-07-17

- ↑ G. K. Zhukov (2002) Воспоминания и размышления. Olma-Press.

- ↑ Mauno Koivisto Venäjän idea, Helsinki. Tammi. 2001.

Bibliography

- Afanasiev, Yuri N., ed. (1989). There Is No Other Way. Hanoi: Social Science Publisher and Truth Publisher.

- Axell, Albert (2003). Marshal Zhukov. Toronto: Pearson Education Ltd. ISBN 0-582-77233-8.

- Chaney, Otto P. (1996). Zhukov – Revised Edition. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2807-0.

- Coox, Alvin D. (1985). Nomonhan; Japan Against Russia, 1939 Two volumes. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-1160-7.

- Isaev, Aleksey V. (2006). Георгий Жуков: Последний довод короля [Zhukov: The Last Argument of the King] (in Russian). Moscow: Yauza. ISBN 5-699-16564-9.

- Shtemenko, Sergei M. (1989). Генеральный штаб в годы войны [The General Staff During the War Years] (in Russian). Moscow: Voenizdat.

- Spahr, William J. (1993). Zhukov: The Rise and Fall of a Great Captain. Novato, CA: Presidio Press. ISBN 0-89141-551-3.

- Thâm, Cố Vân. 10 Đại Tướng soái thế giới.

- Vasilevsky, Aleksandr M. (1978). Дело всей жизни [The Matter of a Whole Life] (in Russian). Moscow: Politizdat.

- Zhukov, Georgy К. (1965). The Memoirs of Marshal Zhukov. 20 years of victory Jubilee edition. Moscow.

- Жуков, Г. К. (2002). Воспоминания и размышления. В 2 т. М. ISBN 5-224-03195-8.

Additional reading

- Goldman, Stuart D. Nomonhan 1939; The Red Army's Victory That Shaped World War II. 2012, Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-329-1.

- Granville, Johanna, trans., "Soviet Archival Documents on the Hungarian Revolution, 24 October – 4 November 1956",

- Cold War International History Project Bulletin, no. 5 (Woodrow Wilson Center for International Scholars, Washington, DC), Spring, 1995, pp. 22–23, 29–34.

- Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr Times of Crisis, in: Apricot Jam and Other Stories. 2012, Counterpoint. ISBN 978-1-61902-008-5.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Georgy Zhukov |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Georgy Zhukov. |

- (in Russian) Shadow of Victory and Take Words Back, books by Viktor Suvorov, highly critical of Zhukov

- (in Serbian) Georgy Zhukov

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Kirill Meretskov |

Chief of the Staff of the Red Army February 1941 – 29 July 1941 |

Succeeded by Boris Shaposhnikov |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Nikolai Bulganin |

Minister of Defence of Soviet Union 9 February 1955 – 26 October 1957 |

Succeeded by Rodion Malinovsky |