Georgian architecture

Georgian architecture is the name given in most English-speaking countries to the set of architectural styles current between 1714 and 1830. It is eponymous for the first four British monarchs of the House of Hanover—George I, George II, George III, and George IV—who reigned in continuous succession from August 1714 to June 1830. The style was revived in the late 19th century in the United States as Colonial Revival architecture and in the early 20th century in Great Britain as Neo-Georgian architecture; in both it is also called Georgian Revival architecture. In the United States the term "Georgian" is generally used to describe all buildings from the period, regardless of style; in Britain it is generally restricted to buildings that are "architectural in intention",[1] and have stylistic characteristics that are typical of the period, though that covers a wide range.

The Georgian style is highly variable, but marked by symmetry and proportion based on the classical architecture of Greece and Rome, as revived in Renaissance architecture. Ornament is also normally in the classical tradition, but typically restrained, and sometimes almost completely absent on the exterior. The period brought the vocabulary of classical architecture to smaller and more modest buildings than had been the case before, replacing English vernacular architecture (or becoming the new vernacular style) for almost all new middle-class homes and public buildings by the end of the period.

Georgian architecture is characterized by its proportion and balance; simple mathematical ratios were used to determine the height of a window in relation to its width or the shape of a room as a double cube. Regularity, as with ashlar (uniformly cut) stonework, was strongly approved, imbuing symmetry and adherence to classical rules: the lack of symmetry, where Georgian additions were added to earlier structures remaining visible, was deeply felt as a flaw, at least before Nash began to introduce it in a variety of styles.[2] Regularity of housefronts along a street was a desirable feature of Georgian town planning. Until the start of the Gothic Revival in the early 19th century, Georgian designs usually lay within the Classical orders of architecture and employed a decorative vocabulary derived from ancient Rome or Greece.

Characteristics

In towns, which expanded greatly during the period, landowners turned into property developers, and rows of identical terraced houses became the norm.[3] Even the wealthy were persuaded to live in these in town, especially if provided with a square of garden in front of the house. There was an enormous amount of building in the period, all over the English-speaking world, and the standards of construction were generally high. Where they have not been demolished, large numbers of Georgian buildings have survived two centuries or more, and they still form large parts of the core of cities such as London, Edinburgh, Dublin, Newcastle upon Tyne and Bristol.

The period saw the growth of a distinct and trained architectural profession; before the mid-century "the high-sounding title, 'architect' was adopted by anyone who could get away with it".[4] This contrasted with earlier styles, which were primarily disseminated among craftsmen through the direct experience of the apprenticeship system. But most buildings were still designed by builders and landlords together, and the wide spread of Georgian architecture, and the Georgian styles of design more generally, came from dissemination through pattern books and inexpensive suites of engravings. Authors such as the prolific William Halfpenny (active 1723–1755) published editions in America as well as Britain.

A similar phenomenon can be seen in the commonality of housing designs in Canada and the United States (though of a wider variety of styles) from the 19th century down to the 1950s, using pattern books drawn up by professional architects that were distributed by lumber companies and hardware stores to contractors and homebuilders.[5] Mail-order kit homes were also popular before World War II.

From the mid-18th century, Georgian styles were assimilated into an architectural vernacular that became part and parcel of the training of every architect, designer, builder, carpenter, mason and plasterer, from Edinburgh to Maryland.[6]

Styles

Georgian succeeded the English Baroque of Sir Christopher Wren, Sir John Vanbrugh, Thomas Archer, William Talman, and Nicholas Hawksmoor; this in fact continued into at least the 1720s, overlapping with a more restrained Georgian style. The architect James Gibbs was a transitional figure, his earlier buildings are Baroque, reflecting the time he spent in Rome in the early 18th century, but he adjusted his style after 1720.[7] Major architects to promote the change in direction from baroque were Colen Campbell, author of the influential book Vitruvius Britannicus (1715–1725); Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington and his protégé William Kent; Isaac Ware; Henry Flitcroft and the Venetian Giacomo Leoni, who spent most of his career in England.

Other prominent architects of the early Georgian period include James Paine, Robert Taylor, and John Wood, the Elder. The European Grand Tour became very common for wealthy patrons in the period, and Italian influence remained dominant,[8] though at the start of the period Hanover Square, Westminster (1713 on), developed and occupied by Whig supporters of the new dynasty, seems to have deliberately adopted German stylisic elements in their honour, especially vertical bands connecting the windows.[9]

The styles that resulted fall within several categories. In the mainstream of Georgian style were both Palladian architecture—and its whimsical alternatives, Gothic and Chinoiserie, which were the English-speaking world's equivalent of European Rococo. From the mid-1760s a range of Neoclassical modes were fashionable, associated with the British architects Robert Adam, James Gibbs, Sir William Chambers, James Wyatt, George Dance the Younger, Henry Holland and Sir John Soane. John Nash was one of the most prolific architects of the late Georgian era known as The Regency style, he was responsible for designing large areas of London.[10] Greek Revival architecture was added to the repertory, beginning around 1750, but increasing in popularity after 1800. Leading exponents were William Wilkins and Robert Smirke.

In Britain brick or stone are almost invariably used;[11] brick is often disguised with stucco. In America and other colonies wood remained very common, as its availability and cost-ratio with the other materials was more favourable. Raked roofs were mostly covered in earthenware tiles until Richard Pennant, 1st Baron Penrhyn led the development of the slate industry in Wales from the 1760s, which by the end of the century had become the usual material.[12]

Types of buildings

Houses

Versions of revived Palladian architecture dominated English country house architecture. Houses were increasingly placed in grand landscaped settings, and large houses were generally made wide and relatively shallow, largely to look more impressive from a distance. The height was usually highest in the centre, and the Baroque emphasis on corner pavilions often found on the continent generally avoided. In grand houses, an entrance hall led to steps up to a piano nobile or mezzanine floor where the main reception rooms were. Typically the basement area or "rustic", with kitchens, offices and service areas, as well as male guests with muddy boots,[13] came some way above ground, and was lit by windows that were high on the inside, but just above ground level outside. A single block was typical, with perhaps a small court for carriages at the front marked off by railings and a gate, but rarely a stone gatehouse, or side wings around the court.

Windows in all types of buildings were large and regularly placed on a grid; this was partly to minimize window tax, which was in force throughout the period in the United Kingdom. Some windows were subsequently bricked-in. Their height increasingly varied between the floors, and they increasingly began below waist-height in the main rooms, making a small balcony desirable. Before this the internal plan and function of the rooms can generally not be deduced from the outside. To open these large windows the sash window, already developed by the 1670s, became very widespread.[14] Corridor plans became universal inside larger houses.[15]

Internal courtyards became more rare, except beside the stables, and the functional parts of the building were placed at the sides, or in separate buildings nearby hidden by trees. The views to and from the front and rear of the main block were concentrated on, with the side approaches usually much less important. The roof was typically invisible from the ground, though domes were sometimes visible in grander buildings. The roofline was generally clear of ornament except for a balustrade or the top of a pediment.[16] Columns or pilasters, often topped by a pediment, were popular for ornament inside and out,[17] and other ornament was generally geometrical or plant-based, rather than using the human figure.

Inside ornament was far more generous, and could sometimes be overwhelming.[18] The chimneypiece continued to be the usual main focus of rooms, and was now given a classical treatment, and increasingly topped by a painting or a mirror.[19] Plasterwork ceilings,[20] carved wood, and bold schemes of wallpaint formed a backdrop to increasingly rich collections of furniture, paintings, porcelain, mirrors, and objets d'art of all kinds.[21] Wood-panelling, very common since about 1500, fell from favour around the mid-century, and wallpaper included very expensive imports from China.[22]

Smaller houses in the country, such as vicarages, were simple regular blocks with visible raked roofs, and a central doorway, often the only ornamented area. Similar houses, often referred to as "villas" became common around the fringes of the larger cities, especially London,[23] and detached houses in towns remained common, though only the very rich could afford them in central London.

In towns even most better-off people lived in terraced houses, which typically opened straight onto the street, often with a few steps up to the door. There was often an open space, protected by iron railings, dropping down to the basement level, with a discreet entrance down steps off the street for servants and deliveries; this is known as the "area".[24] This meant that the ground floor front was now removed and protected from the street and encouraged the main reception rooms to move there from the floor above. Where, as often, a new street or set of streets was developed, the road and pavements were raised up, and the gardens or yards behind the houses at a lower level, usually representing the original one.[25]

Town terraced houses for all social classes remained resolutely tall and narrow, each dwelling occupying the whole height of the building. This contrasted with well-off continental dwellings, which had already begun to be formed of wide apartments occupying only one or two floors of a building; such arrangements were only typical in England when housing groups of batchelors, as in Oxbridge colleges, the lawyers in the Inns of Court or The Albany after it was converted in 1802.[26] In the period in question, only in Edinburgh were working-class purpose-built tenements common, though lodgers were common in other cities. A curving crescent, often looking out at gardens or a park, was popular for terraces where space allowed. In early and central schemes of development, plots were sold and built on individually, though there was often an attempt to enforce some uniformity,[27] but as development reached further out schemes were increasingly built as a uniform scheme and then sold.[28]

The late Georgian period saw the birth of the semi-detached house, planned systematically, as a suburban compromise between the terraced houses of the city and the detached "villas" further out, where land was cheaper. There had been occasional examples in town centres going back to medieval times. Most early suburban examples are large, and in what are now the outer fringes of Central London, but were then in areas being built up for the first time. Blackheath, Chalk Farm and St John's Wood are among the areas contesting being the original home of the semi.[29] Sir John Summerson gave primacy to the Eyre Estate of St John's Wood. A plan for this exists dated 1794, where "the whole development consists of pairs of semi-detached houses, So far as I know, this is the first recorded scheme of the kind". In fact the French Wars put an end to this scheme, but when the development was finally built it retained the semi-detached form, "a revolution of striking significance and far-reaching effect".[30]

Churches

Until the Church Building Act of 1818, the period saw relatively few churches built in Britain, which was already well-supplied,[31] although in the later years of the period the demand for Non-conformist and Roman Catholic places of worship greatly increased.[32] Anglican churches that were built were designed internally to allow maximum audibility, and visibility, for preaching, so the main nave was generally wider and shorter than in medieval plans, and often there were no side-aisles. Galleries were common in new churches. Especially in country parishes, the external appearance generally retained the familiar signifiers of a Gothic church, with a tower or spire, a large west front with one or more doors, and very large windows along the nave, but all with any ornament drawn from the classical vocabulary. Where funds permitted, a classical temple portico with columns and a pediment might be used at the west front. Decoration inside was very limited, but churches filled up with monuments to the prosperous.[33]

In the colonies new churches were certainly required, and generally repeated similar formulae. British Non-conformist churches were often more classical in mood, and tended not to feel the need for a tower or steeple.

The archetypical Georgian church is St Martin-in-the-Fields in London (1720), by Gibbs, who boldly added to the classical temple façade at the west end a large steeple on top of a tower, set back slightly from the main frontage. This formula shocked purists and foreigners, but became accepted and was very widely copied, at home and in the colonies,[34] for example at St Andrew's Church, Chennai in India.

The 1818 Act allocated some public money for new churches required to reflect changes in population, and a commission to allocate it. Building of Commissioners' churches gathered pace in the 1820s, and continued until the 1850s. The early churches, falling into the Georgian period, show a high proportion of Gothic Revival buildings, along with the classically inspired.[35]

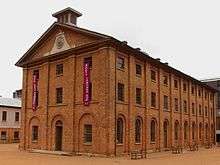

Public buildings

Public buildings generally varied between the extremes of plain boxes with grid windows and Italian Late Renaissance palaces, depending on budget. Somerset House in London, designed by Sir William Chambers in 1776 for government offices, was as magnificent as any country house, though never quite finished, as funds ran out.[36] Barracks and other less prestigious buildings could be as functional as the mills and factories that were growing increasingly large by the end of the period. But as the period came to an end many commercial projects were becoming sufficiently large, and well-funded, to become "architectural in intention", rather than having their design left to the lesser class of "surveyors".[37]

Colonial Georgian architecture

Georgian architecture was widely disseminated in the English colonies during the Georgian era. American buildings of the Georgian period were very often constructed of wood with clapboards; even columns were made of timber, framed up, and turned on an oversized lathe. At the start of the period the difficulties of obtaining and transporting brick or stone made them a common alternative only in the larger cities, or where they were obtainable locally. Dartmouth College, Harvard University, and the College of William and Mary, offer leading examples of Georgian architecture in the Americas.

Unlike the Baroque style that it replaced, which was mostly used for palaces and churches, and had little representation in the British colonies, simpler Georgian styles were widely used by the upper and middle classes. Perhaps the best remaining house is the pristine Hammond-Harwood House (1774) in Annapolis, Maryland, designed by the colonial architect William Buckland and modelled on the Villa Pisani at Montagnana, Italy as depicted in Andrea Palladio's I quattro libri dell'architettura ("Four Books of Architecture").

After independence, in the former American colonies, Federal style architecture represented the equivalent of Regency architecture, with which it had much in common.

Post-Georgian developments

After about 1840, Georgian conventions were slowly abandoned as a number of revival styles, including Gothic Revival, that had originated in the Georgian period, developed and contested in Victorian architecture, and in the case of Gothic became better researched, and closer to their originals. Neoclassical architecture remained popular, and was the opponent of Gothic in the Battle of the Styles of the early Victorian period. In the United States the Federalist Style contained many elements of Georgian style, but incorporated revolutionary symbols.

In the early decades of the twentieth century when there was a growing nostalgia for its sense of order, the style was revived and adapted and in the United States came to be known as the Colonial Revival. In Canada the United Empire Loyalists embraced Georgian architecture as a sign of their fealty to Britain, and the Georgian style was dominant in the country for most of the first half of the 19th century. The Grange, for example, a manor built in Toronto, was built in 1817. In Montreal, English born architect John Ostell worked on a significant number of remarkable constructions in the Georgian style such as the Old Montreal Custom House and the Grand séminaire de Montréal.

The revived Georgian style that emerged in Britain at the beginning of the 20th century is usually referred to as Neo-Georgian; the work of Edwin Lutyens includes many examples. Versions of the Neo-Georgian style were commonly used in Britain for certain types of urban architecture until the late 1950s, Bradshaw Gass & Hope's Police Headquarters in Salford of 1958 being a good example. In both the United States and Britain, the Georgian style is still employed by architects like Quinlan Terry Julian Bicknell and Fairfax and Sammons for private residences.

Gallery

.jpg)

Eastern side of Bryanston Square, London, with its gardens

Eastern side of Bryanston Square, London, with its gardens 18th Century view of the Georgian Royal Exchange in Dublin; one of "Malton's views of Dublin"

18th Century view of the Georgian Royal Exchange in Dublin; one of "Malton's views of Dublin" Connecticut Hall at Yale University (1750)

Connecticut Hall at Yale University (1750) A former guildhall in Dunfermline, Scotland built around 1807 and 1811

A former guildhall in Dunfermline, Scotland built around 1807 and 1811

See also

- Golden ratio

- Jamaican Georgian architecture

- Clifton, Bristol

- Georgian Dublin

- Grainger Town, Newcastle upon Tyne

- New Town, Edinburgh, an 18th and 19th-century development that contains some of the largest surviving examples of Georgian-style architecture and layout.

- Newtown Pery, Limerick

Notes

- ↑ A phrase used by John Summerson, distinguishing among commercial buildings, Summerson, 252

- ↑ Musson, 33–34, 52–53

- ↑ Summerson, 26–28, 73–86

- ↑ Summerson, 47–49, 47 quoted

- ↑ Reiff, Daniel D. (2001). Houses from Books. University Park, Pa.: Penn State University Press. ISBN 9780271019437. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ↑ Summerson, 49–51; The Center for Palladian Studies in America, Inc., "Palladio and Patternbooks in Colonial America."

- ↑ Summerson, 61–70, and see index

- ↑ Jenkins (2003), xiv; Musson, 31

- ↑ Summerson, 73–74

- ↑ Summerson, see index on all these; Jenkins (2003), xv–xiv; Musson, 28–35

- ↑ Summerson, 54–56

- ↑ Summerson, 55

- ↑ Musson, 31; Jenkins (2003), xiv

- ↑ Musson, 73-76; Summerson, 46

- ↑ Bannister Fletcher, 420

- ↑ Musson, 51; Bannister Fletcher, 420

- ↑ Bannister Fletcher, 420

- ↑ Jenkins (2003), xv; Musson, 31

- ↑ Musson, 84–87

- ↑ Musson, 113–116

- ↑ Jenkins (2003), xv

- ↑ Musson, 101–106

- ↑ Summerson, 266–269

- ↑ Summerson, 44–45

- ↑ Summerson, 44–45

- ↑ Summerson, 45

- ↑ Summerson, 73–86

- ↑ Summerson, 147–191

- ↑ correspondence in The Guardian

- ↑ Summerson, 159-160

- ↑ Summerson, 57–72, 206–224; Jenkins (1999), xxii

- ↑ Summerson, 222–224

- ↑ Jenkins (1999), xx–xxii

- ↑ Summerson, 64–70

- ↑ Summerson, 212-221

- ↑ Summerson, 115–120

- ↑ Summerson, 47, 252–262, 252 quoted

- ↑ Sutton Lodge Day Centre website

References

- Bannister, Fletcher and Sir Banister Fletcher, A History of Architecture, 1901 edn., Batsford

- Esher, Lionel, The Glory of the English House, 1991, Barrie and Jenkins, ISBN 0712636137

- Jenkins, Simon (1999), England's Thousand Best Churches, 1999, Allen Lane, ISBN 0-7139-9281-6

- Jenkins, Simon (2003), England's Thousand Best Houses, 2003, Allen Lane, ISBN 0-7139-9596-3

- Musson, Jeremy, How to Read a Country House, 2005, Ebury Press, ISBN 009190076X

- Pevsner, Nikolaus. The Englishness of English Art, Penguin, 1964 edn.

- Sir John Summerson, Georgian London, (1945), 1988 revised edition, Barrie & Jenkins, ISBN 0712620958. (Also see revised edition, edited by Howard Colvin, 2003)

Further reading

- Georgian Residence in Pasadena by architect James V. Coane & Associates

- Howard Colvin, A Biographical Dictionary of British Architects, 3rd ed. 1995.

- John Cornforth, Early Georgian Interiors, (Paul Mellon Centre) 2005.

- James Stevens Curl, Georgian Architecture.

- Christopher Hussey, Early Georgian Houses,, Mid-Georgian Houses,, Late Georgian House,. Reissued in paperback, Antique Collectors Club, 1986.

- Frank Jenkins, Architect and Patron 1961.

- Barrington Kaye, The Development of the Architectural Profession in Britain 1960.

- McAlester, Virginia & Lee, A Field Guide To American Houses 1996 ISBN 0-394-73969-8

- Sir John Summerson, Architecture in Britain (series: Pelican History of Art) Reissued in paperback 1970

- Richard Sammons, The Anatomy of the Georgian Room. Period Homes, March 2006.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Georgian architecture. |