Georges Seurat

| Georges Seurat | |

|---|---|

Georges Seurat, 1888 | |

| Born |

Georges-Pierre Seurat 2 December 1859 Paris, France |

| Died |

29 March 1891 (aged 31) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Painting |

| Notable work | A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte |

| Movement | Post-Impressionism, neo-impressionism, Pointillism |

Georges-Pierre Seurat (French: [ʒɔʁʒ pjɛʁ sœʁa];[1] 2 December 1859 – 29 March 1891) was a French post-Impressionist painter and draftsman. He is noted for his innovative use of drawing media and for devising the painting techniques known as chromoluminarism and pointillism. Seurat's artistic personality was compounded of qualities which are usually supposed to be opposed and incompatible: on the one hand, his extreme and delicate sensibility; on the other, a passion for logical abstraction and an almost mathematical precision of mind.[2] His large-scale work, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884–1886), altered the direction of modern art by initiating Neo-impressionism, and is one of the icons of late 19th-century painting.[3]

Biography

Family and education

Seurat was born 2 December 1859 in Paris, at 60 rue de Bondy (now rue René Boulanger). The Seurat family moved to 136 boulevard de Magenta (now 110 boulevard de Magenta) in 1862 or 1863.[4] His father, Antoine Chrysostome Seurat, originally from Champagne, was a former legal official who had become wealthy from speculating in property, and his mother, Ernestine Faivre, was from Paris.[5] Georges had a brother, Émile Augustin, and a sister, Marie-Berthe, both older. His father lived in Le Raincy and visited his wife and children once a week at boulevard de Magenta.[6]

Georges Seurat first studied art at the École Municipale de Sculpture et Dessin, near his family's home in the boulevard Magenta, which was run by the sculptor Justin Lequien.[7][8] In 1878 he moved on to the École des Beaux-Arts where he was taught by Henri Lehmann, and followed a conventional academic training, drawing from casts of antique sculpture and copying drawings by old masters.[7] Seurat's studies resulted in a well-considered and fertile theory of contrasts: a theory to which all his work was thereafter subjected.[9] His formal artistic education came to an end in November 1879, when he left the École des Beaux-Arts for a year of military service.[8]

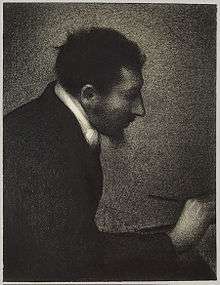

After a year at the Brest Military Academy, he returned to Paris where he shared a studio with his friend Aman-Jean, while also renting a small apartment at 16 rue de Chabrol.[5] For the next two years, he worked at mastering the art of monochrome drawing. His first exhibited work, shown at the Salon, of 1883, was a Conté crayon drawing of Aman-Jean.[10] He also studied the works of Eugène Delacroix carefully, making notes on his use of color.[7]

Bathers at Asnières

He spent 1883 working on his first major painting—a large canvas titled Bathers at Asnières,[11] a monumental work showing young men relaxing by the Seine in a working-class suburb of Paris.[12] Although influenced in its use of color and light tone by Impressionism, the painting with its smooth, simplified textures and carefully outlined, rather sculptural figures, shows the continuing impact of his neoclassical training; the critic Paul Alexis described it as a "faux Puvis de Chavannes".[13] Seurat also departed from the Impressionist ideal by preparing for the work with a number of drawings and oil sketches before starting on the canvas in his studio.[13]

Bathers at Asnières was rejected by the Paris Salon, and instead he showed it at the Groupe des Artistes Indépendants in May 1884. Soon, however, disillusioned by the poor organisation of the Indépendants, Seurat and some other artists he had met through the group – including Charles Angrand, Henri-Edmond Cross, Albert Dubois-Pillet and Paul Signac – set up a new organisation, the Société des Artistes Indépendants.[11] Seurat's new ideas on pointillism were to have an especially strong influence on Signac, who subsequently painted in the same idiom.

A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte

In the summer of 1884, Seurat began work on A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, which took him two years to complete.

The painting shows members of each of the social classes participating in various park activities. The tiny juxtaposed dots of multi-colored paint allow the viewer's eye to blend colors optically, rather than having the colors physically blended on the canvas. It took Seurat two years to complete this 10-foot-wide (3.0 m) painting, much of which he spent in the park sketching in preparation for the work (there are about 60 studies). It is now in the permanent collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Seurat made several studies for the large painting including a smaller version, Study for A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884–1885), now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York City.[14]

The painting was the inspiration for James Lapine and Stephen Sondheim's musical, Sunday in the Park with George.

Later career

%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_95.5_x_79.5_cm%2C_Courtauld_Institute_of_Art.jpg)

Seurat concealed his relationship with Madeleine Knobloch (or Madeleine Knoblock, 1868–1903), an artist's model whom he portrayed in his painting Jeune femme se poudrant. In 1889 she moved in with Seurat in his studio on the 7th floor of 128bis Boulevard de Clichy.[15]

When Madeleine became pregnant, the couple moved to a studio at 39 passage de l'Élysée-des-Beaux-Arts (now rue André Antoine). There she gave birth to their son, who was named Pierre-Georges, 16 February 1890.[15]

Seurat spent the summer of 1890 on the coast at Gravelines, where he painted four canvases including The Channel of Gravelines, Petit Fort Philippe, as well as eight oil panels, and made a few drawings.[16]

Death

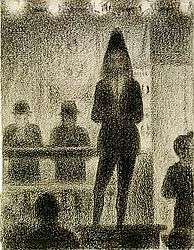

Seurat died in Paris in his parents' home on 29 March 1891 at the age of 31.[4] The cause of his death is uncertain, and has been variously attributed to a form of meningitis, pneumonia, infectious angina, and diphtheria. His son died two weeks later from the same disease.[17] His last ambitious work, The Circus, was left unfinished at the time of his death.

30 March 1891 a commemorative service was held in the church of Saint-Vincent-de-Paul.[4] Seurat was interred 31 March 1891 at Cimetière du Père-Lachaise.[6]

At the time of Seurat's death, Madeleine was pregnant with a second child who died during or shortly after birth.[18]

Color theory

Contemporary ideas

During the 19th century, scientist-writers such as Michel Eugène Chevreul, Ogden Rood and David Sutter wrote treatises on color, optical effects and perception. They adapted the scientific research of Hermann von Helmholtz and Isaac Newton into a form accessible to laypeople. Artists followed new discoveries in perception with great interest.

Chevreul was perhaps the most important influence on artists at the time; his great contribution was producing a color wheel of primary and intermediary hues. Chevreul was a French chemist who restored tapestries. During his restorations he noticed that the only way to restore a section properly was to take into account the influence of the colors around the missing wool; he could not produce the right hue unless he recognized the surrounding dyes. Chevreul discovered that two colors juxtaposed, slightly overlapping or very close together, would have the effect of another color when seen from a distance. The discovery of this phenomenon became the basis for the pointillist technique of the Neoimpressionist painters.

Chevreul also realized that the "halo" that one sees after looking at a color is the opposing color (also known as complementary color). For example: After looking at a red object, one may see a cyan echo/halo of the original object. This complementary color (as an example, cyan for red) is due to retinal persistence. Neoimpressionist painters interested in the interplay of colors made extensive use of complementary colors in their paintings. In his works, Chevreul advised artists to think and paint not just the color of the central object, but to add colors and make appropriate adjustments to achieve a harmony among colors. It seems that the harmony Chevreul wrote about is what Seurat came to call "emotion".

It is not clear whether Seurat read all of Chevreul's book on color contrast, published in 1859, but he did copy out several paragraphs from the chapter on painting, and he had read Charles Blanc's Grammaire des arts du dessin (1867),[7] which cites Chevreul's work. Blanc's book was directed at artists and art connoisseurs. Because of color's emotional significance to him, he made explicit recommendations that were close to the theories later adopted by the Neoimpressionists. He said that color should not be based on the "judgment of taste", but rather it should be close to what we experience in reality. Blanc did not want artists to use equal intensities of color, but to consciously plan and understand the role of each hue in creating a whole.

While Chevreul based his theories on Newton's thoughts on the mixing of light, Ogden Rood based his writings on the work of Helmholtz. He analyzed the effects of mixing and juxtaposing material pigments. Rood valued as primary colors red, green, and blue-violet. Like Chevreul, he said that if two colors are placed next to each other, from a distance they look like a third distinctive color. He also pointed out that the juxtaposition of primary hues next to each other would create a far more intense and pleasing color, when perceived by the eye and mind, than the corresponding color made simply by mixing paint. Rood advised artists to be aware of the difference between additive and subtractive qualities of color, since material pigments and optical pigments (light) do not mix in the same way:

- Material pigments: Red + Yellow + Blue = Black

- Optical / Light : Red + Green + Blue = White

Seurat was also influenced by Sutter's Phenomena of Vision (1880), in which he wrote that "the laws of harmony can be learned as one learns the laws of harmony and music".[19] He heard lectures in the 1880s by the mathematician Charles Henry at the Sorbonne, who discussed the emotional properties and symbolic meaning of lines and color. There remains controversy over the extent to which Henry's ideas were adopted by Seurat.[20]

The language of color

Seurat took to heart the color theorists' notion of a scientific approach to painting. He believed that a painter could use color to create harmony and emotion in art in the same way that a musician uses counterpoint and variation to create harmony in music. He theorized that the scientific application of color was like any other natural law, and he was driven to prove this conjecture. He thought that the knowledge of perception and optical laws could be used to create a new language of art based on its own set of heuristics and he set out to show this language using lines, color intensity and color schema. Seurat called this language Chromoluminarism.

In a letter to the writer Maurice Beaubourg in 1890 he wrote: "Art is Harmony. Harmony is the analogy of the contrary and of similar elements of tone, of colour and of line. In tone, lighter against darker. In colour, the complementary, red-green, orange-blue, yellow-violet. In line, those that form a right-angle. The frame is in a harmony that opposes those of the tones, colours and lines of the picture, these aspects are considered according to their dominance and under the influence of light, in gay, calm or sad combinations".[21][22]

Seurat's theories can be summarized as follows: The emotion of gaiety can be achieved by the domination of luminous hues, by the predominance of warm colors, and by the use of lines directed upward. Calm is achieved through an equivalence/balance of the use of the light and the dark, by the balance of warm and cold colors, and by lines that are horizontal. Sadness is achieved by using dark and cold colors and by lines pointing downward.

Influence

Where the dialectic nature of Paul Cézanne's work had been greatly influential during the highly expressionistic phase of proto-Cubism, between 1908 and 1910, the work of Seurat, with its flatter, more linear structures, would capture the attention of the Cubists from 1911.[23] Seurat in his few years of activity, was able, with his observations on irradiation and the effects of contrast, to create afresh without any guiding tradition, to complete an esthetic system with a new technical method perfectly adapted to its expression.[24]

"With the advent of monochromatic Cubism in 1910–1911," writes art historian Robert Herbert, "questions of form displaced color in the artists' attention, and for these Seurat was more relevant. Thanks to several exhibitions, his paintings and drawings were easily seen in Paris, and reproductions of his major compositions circulated widely among the Cubists. The Chahut [Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo] was called by André Salmon 'one of the great icons of the new devotion', and both it and the Cirque (Circus), Musée d'Orsay, Paris, according to Guillaume Apollinaire, 'almost belong to Synthetic Cubism'."[20]

The concept was well established among the French artists that painting could be expressed mathematically, in terms of both color and form; and this mathematical expression resulted in an independent and compelling "objective truth", perhaps more so than the objective truth of the object represented.[23]

Indeed, the Neo-Impressionists had succeeded in establishing an objective scientific basis in the domain of color (Seurat addresses both problems in Circus and Dancers). Soon, the Cubists were to do so in both the domain of form and dynamics; Orphism would do so with color too.[23]

Paintings

The Suburbs, 1882–83, Musée d'art moderne de Troyes

The Suburbs, 1882–83, Musée d'art moderne de Troyes Fishing in The Seine, 1883, Musée d'art moderne de Troyes

Fishing in The Seine, 1883, Musée d'art moderne de Troyes The Laborers 1883, National Gallery of Art Washington, DC.

The Laborers 1883, National Gallery of Art Washington, DC. Study for A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, 1884–85, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Study for A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, 1884–85, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Bathers at Asnières, 1884, National Gallery, London

Bathers at Asnières, 1884, National Gallery, London View of Fort Samson 1885, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

View of Fort Samson 1885, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg Circus Sideshow (Parade de Cirque), 1887–88, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

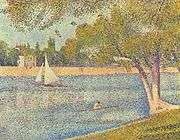

Circus Sideshow (Parade de Cirque), 1887–88, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York The Seine and la Grande Jatte - Springtime 1888, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium

The Seine and la Grande Jatte - Springtime 1888, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium Les Poseuses (The Models), 1888, Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia

Les Poseuses (The Models), 1888, Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia Gray weather, Grande Jatte, 1888, Philadelphia Museum of Art

Gray weather, Grande Jatte, 1888, Philadelphia Museum of Art The Eiffel Tower 1889, California Palace of the Legion of Honor, San Francisco

The Eiffel Tower 1889, California Palace of the Legion of Honor, San Francisco The Circus, 1891, Musée d'Orsay, Paris

The Circus, 1891, Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Drawings

Child in White, 1884-85, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

Child in White, 1884-85, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Seated Nude, Study for Une Baignade, 1883, Scottish National Gallery

Seated Nude, Study for Une Baignade, 1883, Scottish National Gallery L'Écho, study for Une Baignade, Asnières (Bathing Place, Asnières), Yale University Art Gallery

L'Écho, study for Une Baignade, Asnières (Bathing Place, Asnières), Yale University Art Gallery Joueur de trombone (Study for Parade de cirque), private collection

Joueur de trombone (Study for Parade de cirque), private collection

Exhibitions

From 1883 until his death, Seurat exhibited his work at the Salon, the Salon des Indépendants, Les XX in Brussels, the eighth Impressionist exhibition, and various other exhibitions in France and abroad.[25]

- Salon, Paris, 1 May–20 June 1883

The Salon showed Seurat's drawing of Edmond Aman-Jean. - Salon des Indépendants, Paris, 15 May–30 June 1884

Seurat showed Une Baignade, Asnières, after the official Salon had rejected it. Seurat's debut as a painter. - Salon des Indépendants, Paris, 10 December 1884 – 17 January 1885

- Works in Oil and Pastel by the Impressionists of Paris, American Art Association, New York, April and May 1886.

Organised by Paul Durand-Ruel. - Impressionist exhibition, Paris, 15 May–15 June 1886

Un dimanche après-midi à l'Île de la Grande Jatte shown for the first time. - Salon des Indépendants, Paris, 21 August–21 September 1886

- Les impressionnistes, Palais du Cours Saint-André, Nantes, 10 October 1886 – 15 January 1887

- Galerie Martinet, Paris, December 1886 – January 1887

- Les XX, Brussels, February 1887

- Salon des Indépendants, Paris, 26 March–3 May 1887

- Théâtre Libre, Paris, November 1887 – January 1888

Works by Seurat, Signac and van Gogh. - Exposition de Janvier, La Revue indépendante, Paris, January 1888

- Exposition de Février, La Revue indépendante, Paris, February 1888

- Hôtel Drouot, Paris, 1–3 March 1888 (sales exhibition)

- Salon des Indépendants, Paris, 22 March–3 May 1888

- Tweede Jaarlijksche Tentoonstelling der Nederlandsche Etsclub, Arti et Amicitiae, Amsterdam, June 1888

Drawing Au café concert, lent by Theo van Gogh. - Les XX, Brussels, February 1889

- Salon des Indépendants, Paris, 3 September–4 October 1889

- Salon des Indépendants, Paris, 20 March–27 April 1890

Showed Le Chahut, Jeune femme se poudrant and 9 other works. - Les XX, Brussels, 7 February–8 March 1891

Showed Le Chahut and 6 other paintings. - Salon des Indépendants, Paris, 20 March–27 April 1891

Showed Le Cirque and four paintings from Gravelines.

Posthumous exhibitions:

- Solomon R. Guggenheim Collection of Non-Objective Paintings, South Carolina, 1938, Gibbes Memorial Art Gallery[26]

See also

References

- Notes

- ↑ "Seurat", Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary

- ↑ Fry, Roger Essay, 'The Dial', Camden, New Jersey, September 1926

- ↑ "Art Institute of Chicago". Artic.edu. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- 1 2 3 Seurat: p. 16

- 1 2 Georges Seurat, 1859–1891 1991, p. 11.

- 1 2 Seurat: p. 17

- 1 2 3 4 Kirby, Jo; Stonor, Kate; Burnstock, Aviva; Grout, Rachel;Roy, Ashok and White, Raymond (2003). "Seurat's painting Practice: Theory, Development and Technology". National Gallery Technical Bulletin. 24.

- 1 2 Georges Seurat, 1859–1891 1991, p. 12.

- ↑ Signac, Paul Brief Survey, in Revue Blanche Paris 1899

- ↑ Georges Seurat, 1859–1891 1991, p. 48.

- 1 2 Georges Seurat, 1859–1891 1991, p. 148.

- ↑ Georges Seurat, 1859–1891 1991, p. 150.

- 1 2 Georges Seurat, 1859–1891 1991, p. 147–8.

- ↑ Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Retrieved 25 April 2010

- 1 2 Seurat: pp. 18–22

- ↑ Georges Seurat, 1859–1891 1991, p. 360.

- ↑ "''Death of Seurat'', CDC". Cdc.gov. 14 April 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ↑ Seurat: p. 18

- ↑ Hunter, Sam (1992). "Georges Seurat". Modern Art. New York: Harry N. Abrams. p. 27.

- 1 2 Herbert, Robert L., Neo-impressionism, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 1968

- ↑ ''Art of the 20th Century'', Karl Ruhrberg. Books.google.com. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ↑ Letter to the writer Maurice Beaubourg, 28 August 1890, Seurat Phaidon Press, London, 1965

- 1 2 3 Alex Mittelmann, State of the Modern Art World, The Essence of Cubism and its Evolution in Time, 2011

- ↑ Fry, Roger Essay in The Dial, Camden, New Jersey, September 1926.

- ↑ Works exhibited by Georges Seurat. In Seurat, pp. 121–130.

- ↑ "Guggenheim Museum". guggenheim.org.

- Sources

- Georges Seurat, 1859–1891. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1991. ISBN 9780870996184.

- Jooren, Marieke; Veldink, Suzanne; Berger, Helewise (2014). Seurat. Kröller-Müller Museum. ISBN 9789073313286.

- Further reading

- Cachin, Françoise, Seurat: Le rêve de l’art-science, Paris: Gallimard/Réunion des musées nationaux, 1991

- Everdell, William R. (1998). The First Moderns (in Spanish). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-22480-5.

- Fénéon, Félix, Oeuvres-plus-que-complètes, ed., J. U. Halperin, 2v, Geneva: Droz, 1970

- Fry Roger Essay, 'The Dial' Camden, N.J Sept. 1926

- Gage, John T., "The Technique of Seurat: A Reappraisal,” Art Bulletin 69:3 (87 September)

- Halperin, Joan Ungersma, Félix Fénéon: Aesthete and Anarchist in Fin-de-Siècle Paris, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1988

- Homer, William Innes, Seurat and the Science of Painting, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1964

- Lövgren, Sven, The Genesis of Modernism: Seurat, Gauguin, Van Gogh & French Symbolism in the 1880s, 2nd ed., Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1971

- Rewald, John, Cézanne, new ed., NY: Abrams, 1986

- Rewald, Seurat, NY: Abrams, 1990

- Rewald, Studies in Impressionism, NY: Harry N. Abrams, 1986

- Rewald, Post-Impressionism, 3rd ed., revised, NY: Museum of Modern Art, 1978

- Rewald, Studies in Post-Impressionism, NY: Harry N. Abrams, 1986

- Rich, Daniel Catton, Seurat and the Evolution of La Grande Jatte (University of Chicago Press, 1935), NY: Greenwood Press, 1969

- Russell, John, Seurat, (1965) London: Thames & Hudson, 1985

- Seurat, Georges, Seurat: Correspondences, témoignages, notes inédites, critiques, ed., Hélène Seyrès, Paris: Acropole, 1991 (NYU ND 553.S5A3)

- Seurat, ed., Norma Broude, Seurat in Perspective, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1978

- Smith, Paul, Seurat and the Avant-Garde, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1997

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Georges Seurat |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Georges Seurat – Biography, style and artworks

- 106 works by Georges-Pierre Seurat

- Port-en-Bessin, Entrance to the Harbor in the MoMA Online Collection

- George Seurat: The Drawings in the MoMA Online Collection (requires Flash)