George Oppen

| George Oppen | |

|---|---|

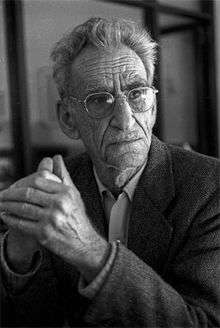

December 1980 Berkeley, CA (Photo by Richard Friedman) | |

| Born |

April 24, 1908 New Rochelle, New York, U.S. |

| Died |

July 7, 1984 (aged 76) California, U.S. |

| Occupation | Poet |

George Oppen (April 24, 1908 – July 7, 1984) was an American poet, best known as one of the members of the Objectivist group of poets. He abandoned poetry in the 1930s for political activism and later moved to Mexico to avoid the attentions of the House Un-American Activities Committee. He returned to poetry — and to the United States — in 1958, and received the Pulitzer Prize in 1969.[1]

Early life

Oppen was born in New Rochelle, New York into a Jewish family. His father, a successful diamond merchant, was George August Oppenheimer (b. Apr. 13, 1881), his mother Elsie Rothfeld. His father changed the family name to Oppen in 1927. Oppen's childhood was one of considerable affluence; the family was well-tended to by servants and maids and Oppen enjoyed all the benefits of a wealthy upbringing: horse riding, expensive automobiles, frequent trips to Europe. But his mother committed suicide when he was four, his father remarried three years later and the boy and his stepmother, Seville Shainwald, apparently could not get along. Oppen developed a skill for sailing at a young age and the seascapes around his childhood home left a mark on his later poetry. He was taught carpentry by the family butler; Oppen, as an adult, found work as a carpenter and cabinetmaker.

In 1917, the family moved to San Francisco where Oppen attended Warren Military Academy. It is speculated that during this time Oppen's early traumas led to fighting and drinking, so that, while reaching maturity, Oppen was also experiencing a personal crisis. By 1925, this period of personal and psychic transition culminated in a serious car wreck in which George was driver and a young passenger was killed. Ultimately, Oppen was expelled from high school just before he graduated. After this period, he traveled to England and Scotland by himself, visiting his stepmother's relative, and attending lectures by C.A. Mace, professor in philosophy at St. Andrews.

In 1926, Oppen started attending Oregon State Agricultural College (what is now Oregon State University). Here he met Mary Colby, a fiercely independent young woman from Grants Pass, Oregon.[2] On their first date, the couple stayed out all night with the result that she was expelled and he suspended. They left Oregon, married, and started hitch-hiking across the country working at odd jobs along the way. Mary documents these events in her memoir, Meaning A Life: An Autobiography (1978).[2]

Early writing

While living on the road, Oppen began writing poems and publishing in local magazines. In 1929 and 1930 he and Mary spent some time in New York, where they met Louis Zukofsky, Charles Reznikoff, musician Tibor Serly, and designer Russel Wright, among others.

In 1929, George came into a small inheritance and relative financial independence. In 1930 George and Mary moved to California and then to France, where, thanks to their financial input, they were able to establish To Publishers and act as printer/publishers with Zukofsky as editor. The short-lived publishing venture managed to launch works by William Carlos Williams and Ezra Pound. Oppen had begun working on poems for what was to be his first book, Discrete Series, a seminal work in early Objectivist history. Some of these appeared in the February 1931 Objectivist issue of Poetry and the subsequent An "Objectivist's" Anthology published in 1932.

Oppen the Objectivist

|

In this situation, as in so many others, I remember with attentiveness the poetry and example of George Oppen, who wanted to look, to see what was out there, evaluate its damage and contradictions, to say scrupulously in a pared and intense language not what was easy or right or neat or consoling, but what he felt when all the platitudes and banalities were stripped away. |

| Rachel Blau DuPlessis[3] |

In 1933, the Oppens returned to New York. George Oppen, William Carlos Williams, Louis Zukofsky and Charles Reznikoff set up the Objectivist Press. The press published books by Reznikoff and Williams, as well as Oppen's first book Discrete Series, which included a preface by Ezra Pound.

Politics and war

Faced with the effects of the depression and the rise of fascism, the Oppens were becoming increasingly involved in political action. Unable to bring himself to write verse propaganda, Oppen abandoned poetry and joined the Communist Party USA, serving as election campaign manager for Brooklyn in 1936, and helping organize the Utica New York Milk Strike.[2] He and Mary were engaged and active in the cause of worker's rights, and Oppen was tried and acquitted on a charge of felonious assault on the police.

By 1942, Oppen was deferred from military service while working in the defense industry. Disillusioned by the CPUSA and willing to assist in the fight against fascism, Oppen quit his job, making himself eligible for the draft. Effectively volunteering for duty, Oppen saw active service on the Maginot Line and the Ardennes; he was seriously wounded south of the Battle of the Bulge. Shortly after Oppen was wounded, Oppen's division helped liberate the concentration camp at Landsberg am Lech. He was awarded the Purple Heart and returned to New York in 1945.

Mexico

|

| Michael Davidson[4] |

After the war, Oppen worked as a carpenter[5] and cabinet maker. Although now less politically active, the Oppens were aware that their pasts were certain to attract the attention of Joseph McCarthy's Senate committee and decided to move to Mexico. During these admittedly bitter years in Mexico, George ran a small furniture making business and was involved in an expatriate intellectual community. They were also kept under surveillance by the Mexican authorities in association with the Federal Bureau of Investigation. They were able to re-enter the United States in 1958 when the United States government again allowed them to obtain passports which had been revoked since 1950.

Return to poetry

In 1958, the Oppens considered becoming involved in Mexican real estate if their expatriate status was to continue. But they were contemplating a move back to the United States, which caused both of them considerable anxiety, prompting Mary to see a therapist. During one of her visits, George told the therapist about a dream he was having (the Oppens later referred to this incident as the "rust in copper" dream). The therapist persuaded George that the dream had a hidden meaning that would convince Oppen to begin writing poetry again.[6] But Oppen also suggested other factors led to his return to the US and to poetry, including his daughter's well-being, because she was beginning college at Sarah Lawrence. After a brief trip in 1958 to visit their daughter at university, the Oppens moved to Brooklyn, New York early 1960 (although for awhile, returning to Mexico regularly for visits). Back in Brooklyn, Oppen renewed old ties with Louis Zukofksy and Charles Reznikoff and also befriended many younger poets. The poems came in a flurry; within two years Oppen had assembled enough poems for a book and began publishing the poems in Poetry, where he had first published, and in his half-sister June Oppen Degnan's San Francisco Review.

|

| Mary Oppen |

The poems of Oppen's first book following his return to poetry, The Materials, were poems that, as he told his sister June, should have been written ten years earlier. Oppen published two more collections of poetry during the 1960s, This In Which (1965) and Of Being Numerous (1968), the latter of which garnered him the Pulitzer Prize in 1969.

Last years

In 1975, Oppen was able to complete and see into publication his Collected Poems, together with a new section "Myth of the Blaze." In 1977, Mary provided the secretarial help George needed to complete his final volume of poetry Primitive. During this time, George's final illness, Alzheimer's disease, began to manifest itself with confusion, failing memory, and other losses. The disease was eventually to make it impossible for him to continue writing. George Oppen, age 76, died of pneumonia with complications from Alzheimer's disease in a convalescent home in California on July 7, 1984.

Selected bibliography

- Discrete Series (1934), with a "Preface" by Ezra Pound

- The Materials (1962)

- This in Which (1965)

- Of Being Numerous (1968)

- Seascape: Needle's Eye (1972)

- The Collected Poems (1975) includes Myth of the Blaze

- Primitive (1978)

- New Collected Poems (2001, revised edition 2008); edited with an "Introduction" & notes by Michael Davidson, w/ a "Preface" by Eliot Weinberger

- Selected Poems (2002), edited, with an "Introduction," by Robert Creeley

Posthumous publications

- For more information on Oppen's posthumous publications, such as his Selected Letters and New Collected Poems, see Wikipedia articles on Rachel Blau DuPlessis and Michael Davidson.

Further reading

- Oppen, Mary, Meaning A Life: An Autobiography, Santa Barbara, Calif: Black Sparrow Press, 1978.

- Hatlen, Burton, ed., George Oppen: Man and Poet (Man/Woman and Poet Series) (Man and Poet Series), National Poetry Foundation, 1981. ISBN 0-915032-53-8

- DuPlessis, Rachel Blau, ed., The Selected Letters of George Oppen, Duke University Press, 1990.

- Oppen, George. Selected Prose, Daybooks, and Papers, edited and with an introduction by Stephen Cope. University of California Press, 2007; ISBN 978-0-520-23579-3, paperback: ISBN 978-0-520-25232-5'.

- Heller, Michael, Speaking the Estranged: Essays on the Work of George Oppen, Cambridge UK: Salt Publishing, 2008.

- Shoemaker, Steven, ed., Thinking Poetics: Essays on George Oppen, Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press, 2009.

- Swigg, Richard, ed.,Speaking with George Oppen: Interviews with the Poet and Mary Oppen, 1968-1987, Jefferson, North Carolina and London, McFarland & Company, 2012. ISBN 978-0-786-46-7884

- Swigg, Richard,George Oppen: The Words in Action, Lewisburg, Bucknell University Press, 2016. ISBN 978-1-61148-749-7

References

- ↑ Miranda Popkey (2012-03-15). "Boy’s Room". The Paris Review. Retrieved 2012-03-16.

- 1 2 3 Popkey, Miranda (8 March 2017). "When the Oppens Gave Up Art to Fight Fascism". The New Yorker.

- ↑ Statement for Pores

- ↑ "Forms of Refusal: George Oppen's Distant Life" (1967), Sulfur No. 26 (Spring 1990), editor Clayton Eshleman (Ypsilanti, MI: Eastern Michigan University) p. 133.

- ↑ Popkey, Miranda. "The Poem Stuck in My Head: George Oppen’s “Boy’s Room”".

- ↑ Richard Swigg, ed. (2012). Speaking with George Oppen: Interviews with the Poet and Mary Oppen, 1968-1987. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. p. 221.

GO: “How to Prevent Rot, Rust, and Copper.” It was one of those dreams in which you fool yourself. I woke up laughing hilariously and saying I’m unfair to my father even in my dreams—and I told this to the psychiatrist still laughing, and of course that I was laughing outrageously was duck soup to the psychiatrist who said, “You dreamt that you’re not going to rot.” And I said thank you and went home. MO: And bought your paper and pencil on the way home.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: George Oppen |

- Oppen exhibits, sites, and homepages

- Academy of American Poets: George Oppen A brief biography of Oppen, poems, and excerpts from a 1964 recording of the poet.

- George Oppen at Poetryfoundation.org this site includes links to a dozen or so Oppen poems & an article on the poet by Carl Phillips

- Oppen at Modern American Poetry

- Register of the George Oppen Papers in the Mandeville Special Collections Library at UC San Diego

- George Oppen Homepage at Electronic Poetry Center

- Others on Oppen

- "The Phenomenal Oppen" by Forrest Gander at Academy of American Poets and first published at NO: A Journal of the Arts

- Parts, Pairs and Positions: A Reading of George Oppen's 'Discrete Series', essay by Richard Swigg, in Jacket Magazine 37 (online), June 2009.

- George Oppen and Martin Heidegger: The Philosophy and Poetry of Gelassenheit, and the Language of Faith essay by Burt Kimmelman, published in Jacket Magazine 37 (Late 2009)

- Seeing the World: The Poetry of George Oppen essay by Jeremy Hooker, first published in Not comfort/But Vision: Essays on the Poetry of George Oppen(Interim Press, 1987)

- George Oppen in Exile: Mexico and Maritain (For Linda Oppen) essay by Peter Nicholls

- Finding the Phenomenal Oppen on-line reprint of an essay in verse by Forrest Gander which first appeared in No: a journal of the arts

- OPPEN TALK by Kevin Killian transcription of The Tenth Annual George Oppen Memorial Lecture on Twentieth Century Poetics (1995) presented by the Poetry Center & American Poetry Archives of San Francisco State University

- The Romantic Poetics of George Oppen thesis on Of Being Numerous

- "I was somewhere in the vicinity of 20 to 22-years-old when..." Here poet Ron Silliman recalls first meeting Oppen at an anti-war reading. This brief essay was published on April 7, 2008 before Silliman was set to attend "A Celebration of George Oppen’s 100th Birthday: 100 Minutes of talk & poetry" at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia

- The Test of Belief: or Why George Oppen Quarrelled with Denise Levertov, an essay by Richard Swigg in "Jacket 2" (online),November 2012.

- Multimedia presentations

- The Shape of Disclosure: George Oppen Centennial Symposium Audio from the Oppen Centennial symposium in NYC, held at the Tribeca Performing Arts Center, April 8, 2008. Features Panel talks, presentations, as well as readings from Oppen's work

- Jacket Magazine Special Feature on George Oppen

- All This Strangeness: A Garland for George Oppen (Big Bridge Special Feature on George Oppen)