Tolpuddle Martyrs

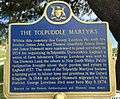

The shelter erected as a memorial in 1934 | |

| Date | 1833 |

|---|---|

| Location | Tolpuddle, Dorset, England |

| Participants |

|

| Outcome | Transported to Australia, pardoned, returned to England |

The Tolpuddle Martyrs were a group of 19th-century Dorset agricultural labourers who were arrested for and convicted of swearing a secret oath as members of the Friendly Society of Agricultural Labourers. The rules of the society show it was clearly structured as a friendly society and operated as a trade-specific benefit society. At the time, friendly societies had strong elements of what are now considered to be the predominant role of trade unions. On 18 March 1834,[1] the Tolpuddle Martyrs were sentenced to penal transportation to Australia.[2]

Historical events

Background

Before 1824 the Combination Acts had outlawed "combining" or organising to gain better working conditions. In 1824/25 these acts were repealed, so trade unions were no longer illegal. In 1833, six men from Tolpuddle in Dorset founded the Friendly Society of Agricultural Labourers to protest against the gradual lowering of agricultural wages.[3]

These Tolpuddle labourers refused to work for less than 10 shillings a week, although by this time wages had been reduced to seven shillings and were due to be further reduced to six. The society, led by George Loveless, a Methodist local preacher, met in the house of Thomas Standfield.[4]

Groups such as the Tolpuddle Martyrs would often use a skeleton painting as part of their initiation process. The newest member would be blindfolded and made to swear a secret oath of allegiance. The blindfold would then be removed and they would be presented with the skeleton painting. This was to warn them of their own mortality but also to remind them of what happens to those who break their promises. An example of this skeleton painting is on display at the People's History Museum, Manchester.[5]

Prosecution and sentencing

In 1834, James Frampton, a local landowner and magistrate, wrote to Home Secretary Lord Melbourne to complain about the union. Melbourne recommended invoking the Unlawful Oaths Act 1797, an obscure law promulgated in 1797 in response to the Spithead and Nore mutinies, which prohibited the swearing of secret oaths. James Brine, James Hammett, George Loveless, George's brother James Loveless, George's brother in-law Thomas Standfield, and Thomas's son John Standfield were arrested and tried before Sir John Williams in R v Lovelass and Others.[6] They were found guilty and transported to Australia.[7][8]

When sentenced to seven years' penal transportation, George Loveless wrote on a scrap of paper lines from the union hymn "The Gathering of the Unions":[9][10][11]

God is our guide! from field, from wave,

From plough, from anvil, and from loom;

We come, our country's rights to save,

And speak a tyrant faction's doom:

We raise the watch-word liberty;

We will, we will, we will be free!

Transportation, pardon, return

James Loveless, the two Standfields, Hammett and Brine sailed on the Surry to Sydney, where they arrived on 17 August 1834. George Loveless was delayed due to illness and left later on the William Metcalf to Van Diemen's Land, reaching Hobart on 4 September.[12]

Of the five who landed in Sydney, Brine and the Standfields were assigned as farm labourers to free settlers in the Hunter Valley. Hammett was assigned to the Queanbeyan farm of Edward John Eyre, and James Loveless was assigned to a farm at Strathallan. In Hobart, George Loveless was assigned to the viceregal farm of Lieutenant Governor Sir George Arthur.[13][14]

In England they became popular heroes and 800,000 signatures were collected for their release. Their supporters organised a political march, one of the first successful marches in the UK, and all were pardoned, on condition of good conduct, in March 1836, with the support of Lord John Russell, who had recently become home secretary.[15]

When the pardon reached George Loveless some delay was caused in his leaving due to no word from his wife as to whether she was to join him in Van Diemen’s Land. On 23 December 1836, a letter was received to the effect that she was not coming and Loveless sailed from Van Diemen’s Land on 30 January 1837, arrived in England on 13 June 1837.[16][17]

In New South Wales, there were delays in obtaining an early sailing due to tardiness in the authorities confirming good conduct with the convicts' assignees and then getting them released from their assignments. James Loveless, Thomas and John Stanfield, and James Brine departed Sydney on the John Barry on 11 September 1837, reaching Plymouth on 17 March 1838, one of the departure points for convict transport ships. A plaque next to the Mayflower Steps in Plymouth's historical Barbican area commemorates the arrival. Although due to depart with the others, James Hammett was detained in Windsor, charged with an assault, while the others left the colony. It was not until March 1839 that he sailed, arriving in England in August 1839.[16][17][14]

Later life

The Lovelesses, Standfields and Brine first settled on farms near Chipping Ongar, Essex, then moved to London, Ontario, Canada, where there is now a monument in their honour and an affordable housing co-op and trade union complex named after them. George Loveless is buried in Siloam Cemetery on Fanshawe Park Road East in London, Ontario. James Brine is buried in St. Marys Cemetery, St. Marys, Ontario. He died in 1902, having lived in nearby Blanshard Township since 1868. Hammett remained in Tolpuddle and died in the Dorchester workhouse in 1891.[16]

Tolpuddle Martyrs Museum

The Tolpuddle Martyrs Museum in Tolpuddle, Dorset, features displays and interactive exhibits about the martyrs and their effect on trade unionism.[18]

Cultural and historical significance

A monument was erected in their honour in Tolpuddle in 1934, and a sculpture of the martyrs, made in 2001, stands in the village in front of the Tolpuddle Martyrs Museum.[19]

The Tolpuddle Martyrs festival is held annually in Tolpuddle, usually in the third week of July, organised by the Trades Union Congress (TUC) featuring a parade of banners from many trade unions, a memorial service, speeches and music. Recent festivals have featured speakers such as Tony Benn and musicians such as Billy Bragg and local folk singers including Graham Moore, as well as others from all around the world.[20]

The courtroom where the martyrs were tried, which has been little altered in 200 years, in Dorchester's Shire Hall, is being preserved as part of a heritage scheme.[21]

The story of Tolpuddle has enriched the history of trade unionism, but the significance of the Tolpuddle Martyrs continues to be debated since Sidney and Beatrice Webb wrote the History of Trade Unionism (1894) and continues with such works as Bob James's Craft Trade or Mystery (2001).[22][23]

There are streets named in their honour in:

In 1984, a mural was created in Edward Square, off Copenhagen Street, Islington, to commemorate the gathering of people organised by the Central Committee of the Metropolitan Trade Unions to demonstrate against the penal transportation of the Tolpuddle Martyrs to Australia. The mural was painted by artist David Bangs.[24]

Comrades is a 1986 British historical drama film directed by Bill Douglas and starring an ensemble cast including James Fox, Robert Stephens and Vanessa Redgrave. Through the pictures of a travelling lanternist, it depicts the story of the Tolpuddle Martyrs.[25]

The Tolpuddle Martyrs also find reference in a poem by Daljit Nagra: "Vox Populi, Vox Dei".

Image gallery

The Tolpuddle Martyrs' Museum.

The Tolpuddle Martyrs' Museum. Tolpuddle Martyrs' Festival in 2004.

Tolpuddle Martyrs' Festival in 2004. Tolpuddle Martyrs' memorial sculpture (London, Ontario, Canada) Leslie Putnam & David Bobier Artists.

Tolpuddle Martyrs' memorial sculpture (London, Ontario, Canada) Leslie Putnam & David Bobier Artists. Tolpuddle Martyrs plaque, Siloam Cemetery, London, Ontario, Canada.

Tolpuddle Martyrs plaque, Siloam Cemetery, London, Ontario, Canada. Gravestone of George Loveless in Siloam Cemetery, London, Ontario, Canada.

Gravestone of George Loveless in Siloam Cemetery, London, Ontario, Canada.

See also

References

- ↑ Judge, Ben. "18 March 1834: Tolpuddle Martyrs sentenced to transportation". Money Week. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ↑ Davis, Graham (2011). In Search of a Better Life: British and Irish Migration. The History Press. p. 94. ISBN 9780752474601. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- ↑ The Tolpuddle Martyrs. Available at: http://www.historytoday.com/john-stevenson/tolpuddle-martyrs (Accessed: 27 October 2016)

- ↑ Burwick, Frederick (2015). British Drama of the Industrial Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 83. ISBN 9781107111653. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- ↑ Collection highlights, Secret Society Skeleton Painting, People's History Museum

- ↑ (1834) 6 Carrington and Payne 596, 172 E.R. 1380; also reported in (1834) 1 Moody and Robinson 349, 174 E.R. 119

- ↑ Anon (2009). Crime and Punishment in Staffordshire. Staffordshire Arts and Museum Service.

- ↑ Evatt, Herbert Vere (2009). "Melbourne suggests prosecution for secret oaths". The Tolpuddle Martyrs: Injustice Within the Law. Sydney: Sydney University Press. p. 10. ISBN 9781920899493. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- ↑ Thompson, Denys (1978). "The Romantics and the Industrial Revolution". The Uses of Poetry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 161. ISBN 9780521292870. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- ↑ Jones, William (1832). Biographical Sketches of the Reform Ministers; with a history of the passing of the Reform Bills. London: Fisher, Fisher and Jackson. p. 758. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- ↑ Loveless, George (1837). The Victims of Whiggery. p. 17. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- ↑ Loveless, George (1837). The Victims of Whiggery. p. 7. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- ↑ Moore, Tony (2011). Death Or Liberty: Rebel Exiles in Australia 1788 - 1868. ReadHowYouWant.com. p. 264. ISBN 9781459621008. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- 1 2 Loveless, James; Brine, James; Standfield, John; Standfield, Thomas (1838). A Narrative of the sufferings of J. Loveless, J. Brine, and T. & J. Standfield, four of the Dorchester Labourers; displaying the horrors of transportation, written by themselves. London: John Cleave.

- ↑ Political Marching: What's at risk? BBC News, 27 November 2010

- 1 2 3 Rudé, rge (1967). "Loveless, George (1797–1874)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

- 1 2 Loveless, George (1837). The Victims of Whiggery. p. 8. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- ↑ Graham, Brian; Howard, Peter, eds. (2012). "Heritage, gender and identity". The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate Publishing. p. 171. ISBN 9781409487609. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- ↑ "The Tolpuddle Martyrs". London and District Labour Council. London and District Labour Council. 2001. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- ↑ "Tolpuddle Martyrs’ Festival" (pdf). TUC. Trade Union Congress. 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- ↑ "Tolpuddle Martyrs courtroom to be centre-piece of new Dorset heritage centre". Western Gazette. 16 July 2014. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- ↑ Labor's Heritage: Quarterly of the George Meany Memorial Archives. Silver Spring, MD: George Meany Memorial Archives. 2004. p. 71.

- ↑ James, Bob (2002). Craft, Trade or Mystery - Part One - Britain from Gothic Cathedrals to the Tolpuddle Conspirators. Tighes Hill, NSW: Takver's Initiatives. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- ↑ "Tolpuddle Martyrs Mural". London Mural Preservation Society. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- ↑ Shail, Robert (2007). "Bill Douglas". British Film Directors: A Critical Guide. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 58. ISBN 9780748622313. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

Further reading

- Tolpuddle Martyrs' Story Tolpuddle Martyrs Museum Trust

- Sidney Webb and Beatrice Webb, The History of Trade Unionism (1894) ch III, 'The Revolutionary Period', 144 ff on Tolpuddle's Dorchester Labourers

- Craft Trade or Mystery (2001) Dr Bob James

- The Book of the Martyrs of Tolpuddle 1834–1934, London : The Trades Union Congress General Council (1934) – Memorial Volume (printed by the Pelican Press) 240 pages. Modern reprint (1999) Tolpuddle Martyrs Memorial Trust, ISBN 1-85006-501-2

- Harris, "Brian, "Injustice", Sutton Publishing. 2006. ISBN 0-7509-4021-2 (An analysis of the trial)

- Marlow, Joyce, The Tolpuddle Martyrs, London : History Book Club, (1971) and Grafton Books, (1985) ISBN 0-586-03832-9

- Tolpuddle – an historical account through the eyes of George Loveless. Contemporary accounts, letters, documents, etc., compiled by Graham Padden, TUC, 1984, updated 1997.

- "The Martyrs of Tolpuddle – Settlers in Canada". Geoffrey R. Anderson 2002. A privately published 70-page booklet available at the London Public Library, and also at the Regional Collection, UWO

- Dorset Pioneers: Jack Dwyer: The History Press: 2009: ISBN 978-0-7524-5346-0

- "TOLPUDDLE MARTYR; Pioneer Farmer, James Brine in Canada 1844 – 1902". Don Macintyre 2010. Privately published 71-page booklet available at St. Marys Museum and St. Marys Library, St. Marys, Ontario, Huron County Library, Ontario; Middlesex County Library, Ontario; London Public Library, Ontario; Dorset County Library, England. ISBN 978-0-9866023-0-6.

- Hollis, Patricia, Class and conflict in nineteenth-century England, 1815–1850, Birth of modern Britain series, International Library of Sociology and Social Reconstruction, Routledge, 1973, ISBN 0-7100-7419-0

- Dorset History Centre holds relevant books and original records (including the Dorchester prison register in which the Martyrs are listed)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tolpuddle Martyrs. |

- The Tolpuddle Martyrs Museum

- 2009 Commemoration of the 1834 Grand Demonstration in support of the Martyrs

- The Tolpuddle Martyrs. Witness. BBC World Service. 17 August 2015.

- Works by or about Tolpuddle Martyrs at Internet Archive

- Works by Tolpuddle Martyrs at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)