George Sisler

| George Sisler | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| First baseman / Manager | |||

|

Born: March 24, 1893 Manchester, Ohio | |||

|

Died: March 26, 1973 (aged 80) Richmond Heights, Missouri | |||

| |||

| MLB debut | |||

| June 28, 1915, for the St. Louis Browns | |||

| Last MLB appearance | |||

| September 22, 1930, for the Boston Braves | |||

| MLB statistics | |||

| Batting average | .340 | ||

| Hits | 2,812 | ||

| Home runs | 102 | ||

| Runs batted in | 1,175 | ||

| Managerial record | 218–241 | ||

| Winning % | .475 | ||

| Teams | |||

|

As player As manager | |||

| Career highlights and awards | |||

| |||

| Member of the National | |||

| Inducted | 1939 | ||

| Vote | 85.8% (fourth ballot) | ||

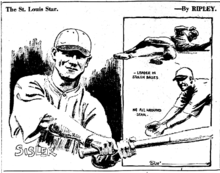

George Harold Sisler (March 24, 1893 – March 26, 1973), nicknamed "Gentleman George" and "Gorgeous George", was an American professional baseball player for 15 seasons, primarily as first baseman with the St. Louis Browns. From 1920 until 2004, Sisler held the Major League Baseball (MLB) record for most hits in a single season; it was broken by Ichiro Suzuki.

Sisler's 1922 season — during which he batted .420, hit safely in a then-record 41 consecutive games, led the American League in hits (246), stolen bases (51), triples (18), and was probably the best fielding first baseman in the game — is considered by many historians to be among the best individual all-around single-season performances in baseball history.[1]

After Sisler retired as a player, he worked as a major league scout and aide. He was on a team of scouts appointed by Branch Rickey to find black players for the Brooklyn Dodgers; the team's work resulted in the signing of Jackie Robinson. Sisler was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1939.[2] In 1999 editors at The Sporting News named him 33rd on their list of "Baseball's 100 Greatest Players."

Early life

Sisler was born in the unincorporated hamlet of Manchester (now part of the city of New Franklin, a suburb of Akron, Ohio[3]). His paternal ancestors were immigrants from Northern Germany in the middle of the 19th century. When he was 14, Sisler moved to Akron to live with his older brother so that he could attend an accredited high school. When Sisler was a high school senior, his brother died of tuberculosis but Sisler was able to move in with a local family and finish school.[4]

In 1911, Sisler signed a contract with the Pittsburgh Pirates to play minor league baseball in the Ohio–Pennsylvania League, but he never played in the league or earned any money.[5] He played college baseball for the University of Michigan. As a freshman, Sisler struck out 20 batters in seven innings during a 1912 game.[6] He lettered in baseball from 1913 to 1915.[7] At Michigan he played for coach Branch Rickey and he earned a degree in mechanical engineering.[5]

After his graduation from Michigan, Sisler sought legal advice from Rickey about the status of his contract with Pittsburgh. The three-time Vanity Fair All-American had become highly sought-after by major league scouts. Rickey talked to Pittsburgh owner Barney Dreyfuss about releasing Sisler from the contract he had signed as a minor, but Dreyfuss maintained his claim to Sisler. Rickey wrote to the National Commission, baseball's governing body, who ruled that the contract was illegal. Rickey, now managing the St. Louis Browns, signed Sisler to a contract worth $7,400.[5]

Major league career

Sisler entered the major leagues as a pitcher for the Browns in 1915. He posted a career pitching record of 5–6 with a 2.35 earned run average in 24 career mound appearances.[8] He defeated Walter Johnson twice in complete-game victories. In 1916, he moved to first base and finished the season with a batting average above .300 for the first of seven consecutive seasons. He also had 34 stolen bases that season; he stole at least 28 bases in every season through 1922.[8]

.png)

In 1917, Sisler hit .353, registered 190 hits and stole 37 bases. The next year he hit .341 and stole a league-leading 45 bases.[8] He then enlisted in the army, joining several major league players in a Chemical Warfare Service unit commanded by Rickey. Sisler was preparing to go overseas when World War I ended that November.[9]

In 1920, Sisler played every inning of each game.[10] He stole 42 bases (second in the American League), collected a major league-leading 257 hits for an average of .407 and ended the season by hitting .442 in August and .448 in September.[8] His batting average was the highest ever for a 600+ at-bat performance. In breaking Ty Cobb's 1911 record for hits in a single season, Sisler established a mark which stood until Ichiro Suzuki broke the record with 262 hits in 2004. (Suzuki, however, collected his hits over 161 games during the modern 162-game season as opposed to 154 in Sisler's era.) Sisler finished second in the AL in doubles and triples, as well as second to Babe Ruth in RBIs and home runs.

Jim Barrero of the Los Angeles Times asserts that Sisler's record was largely overshadowed by Ruth's 54 home runs that season. "Of course, Ruth's obliteration of the home run record drew all the attention from fans and newspapermen, while Sisler's mark was pushed to the side and perhaps left unappreciated during what was a golden age of pure hitters", Barrero wrote.[10] As his popularity increased, Sisler drew comparisons to Cobb, Ruth and Tris Speaker. Sisler, however, was much more reserved than those three stars. A writer named Floyd Bell described Sisler as "modest, almost to a point of bashfulness, as far from egotism as a blushing debutante... Shift the conversation to Sisler himself and he becomes a clam."[11]

In 1922, Sisler hit safely in 41 consecutive games – an American League record that stood until Joe DiMaggio broke it in 1941. His .420 batting average is the third-highest of the 20th century, surpassed only by Rogers Hornsby's .424 in 1924 and Nap Lajoie's .426 in 1901. He was chosen as the AL's Most Valuable Player that year,[8] the first year an official league award was given, as the Browns finished second to the New York Yankees. Sisler stole over 25 bases in every year from 1916 through 1922, peaking with 51 the last year and leading the league three times; he also scored an AL-best 134 runs, and hit 18 triples for the third year in a row.

A severe attack of sinusitis caused him double vision in 1923, forcing him to miss the entire season. He defied some predictions by returning in 1924 with a batting average over .300. Sisler later said, "I planned to get back in uniform for 1924. I just had to meet a ball with a good swing again, and then run. The doctors all said I'd never play again, but when you're fighting for something that actually keeps you alive – well, the human will is all you need."[5] Sisler never regained his previous level of play, though he continued to hit over .300 in six of his last seven seasons and led the AL in stolen bases for a fourth time in 1927.[8]

In 1928, the Browns sold Sisler's contract to the Washington Senators, who in turn sold the contract to the Boston Braves in May. After batting .340, .326, and .309 in his three years in Boston, he ended his major league career with the Braves in 1930, then played in the minor leagues. He accumulated a .340 lifetime batting average over his 16 years in the majors. Sisler stole 375 bases during his career. He became one of the early entrants elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame when he was selected in 1939.[8]

Later life and legacy

After his playing career, Sisler reunited with Rickey as a special assignment scout and front-office aide with the St. Louis Cardinals, Brooklyn Dodgers and Pittsburgh Pirates. Sisler and Rickey worked with future Hall of Famer Duke Snider to teach the young Dodgers hitter to accurately judge the strike zone.[12] Sisler was part of a scouting corps that Rickey assigned to look for black players, though the scouts thought they were looking for players to fill an all-black baseball team separate from MLB. Sisler evaluated Jackie Robinson as a potential star second baseman, but he was concerned about whether Robinson had enough arm strength to play shortstop.[13] With the Pirates in 1961, Sisler had Roberto Clemente switch to a heavier bat. Clemente won the league batting title that season.[14]

Sisler's sons Dick and Dave were also major league players in the 1950s. Sisler was a Dodgers scout in 1950 when his son Dick hit a game-winning home run against Brooklyn to clinch the pennant for the Phillies and eliminate the second-place Dodgers. When asked after the pennant winning game how he felt when his son beat his current team, the Dodgers, George replied, "I felt awful and terrific at the same time."[15] A passage in The Old Man and the Sea refers to Dick Sisler's long home run drives.[14] Another son, George Jr., served as a minor league executive and as the president of the International League.

Sisler also spent some time as commissioner of the National Baseball Congress.[16] He died in Richmond Heights, Missouri, in 1973, while still employed as a scout for the Pirates.

Outside of St. Louis' Busch Stadium, there is a statue honoring Sisler. He is also honored with a star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame.[17] In October 2004, Ichiro Suzuki broke Sisler's 84 years old hit record, collecting his 258th hit off of Texas Rangers pitcher Ryan Drese. Sisler's daughter Frances Sisler Drochelman and other of his family members were in attendance when the record was broken.[18] While in St. Louis for the 2009 All-Star game, Ichiro Suzuki visited Sisler's grave site.[19]

See also

- Major League Baseball titles leaders

- List of Major League Baseball hit records

- List of Major League Baseball career hits leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career doubles leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career triples leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs batted in leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career stolen bases leaders

- List of Major League Baseball batting champions

- List of Major League Baseball annual runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual stolen base leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual triples leaders

- List of Major League Baseball player-managers

- List of baseball players who went directly to Major League Baseball

- List of Major League Baseball players to hit for the cycle

- List of Major League Baseball single-game hits leaders

- University of Michigan Athletic Hall of Honor

Notes

- ↑ Kennedy, Kostya (March 14, 2011). The Streak. Sports Illustrated Magazine, Volume 14, No.ll, p. 64.

- ↑ "St. Louis Browns franchise". sportsecyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2007-07-16.

- ↑ DeLorme. Ohio Atlas & Gazetteer. 7th ed. Yarmouth: DeLorme, 2004, p. 51. ISBN 0-89933-281-1.

- ↑ Lowenfish, Lee (2009). Branch Rickey: Baseball's Ferocious Gentleman. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 53–55. ISBN 0803224532.

- 1 2 3 4 Warburton, Paul (2010). Signature Seasons: Fifteen Baseball Legends at Their Most Memorable, 1908–1949. McFarland. pp. 68–79. ISBN 0786457732.

- ↑ Cook, William (2007). August "Garry" Herrmann: A Baseball Biography. McFarland. p. 190. ISBN 0786430737.

- ↑ Ballew, Bill (2012). "Team spotlight: Maloney looks to build on Michigan's baseball tradition" (PDF). Baseball The Magazine. Retrieved April 30, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "George Sisler". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- ↑ Huhn, pp. 73-74.

- 1 2 Barrero, Jim (September 15, 2000). "Out of sight". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 30, 2014.

- ↑ Huhn, p. 114.

- ↑ McDonald, William (2011). The Obits: The New York Times Annual 2012. Workman Publishing Company. p. 315. ISBN 0761169423.

- ↑ Tygiel, Jules (1997). Baseball's Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy. Oxford University Press. pp. 56–59. ISBN 0195106202.

- 1 2 Cushing, Rick (2010). 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates: Day by Day: A Special Season, an Extraordinary World Series. Dorrance Publishing Co. p. 380. ISBN 1434904989.

- ↑ "Sisler vs. Sisler". Toledo Blade. 1950-10-02. p. 24.

- ↑ Stein, Fred (2002). And the Skipper Bats Cleanup: A History of the Baseball Player-manager, with 42 Biographies of Men who Filled the Dual Role. McFarland. pp. 162–166. ISBN 0786462671.

- ↑ St. Louis Walk of Fame. "St. Louis Walk of Fame Inductees". stlouiswalkoffame.org. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ↑ "258...plus 1". SportsIllustrated.CNN.com. 2005-10-01. Retrieved 2012-08-21.

- ↑ Ichiro Suzuki pays respects at George Sisler's gravesite – ESPN

References

- Huhn, Rick (2013). The Sizzler: George Sisler, Baseball's Forgotten Great. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0826264212.

External links

![]() Media related to George Sisler at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to George Sisler at Wikimedia Commons

- Career statistics and player information from Baseball-Reference, or Fangraphs, or The Baseball Cube

- George Sisler at Find a Grave

| Preceded by Eduard Benes |

Cover of Time Magazine 30 March 1925 |

Succeeded by John Ringling |

| Records | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Ty Cobb |

Single season base hit record holders 1920–2004 |

Succeeded by Ichiro Suzuki |