Ziprasidone

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Geodon, Zeldox, Zipwell |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a699062 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | Oral (capsules), IM |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability |

60% (oral)[1] 100% (IM) |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (aldehyde reductase) |

| Biological half-life | 7 to 10 hours[2] |

| Excretion | Urine and feces |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.106.954 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

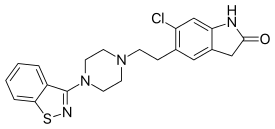

| Formula | C21H21ClN4OS |

| Molar mass | 412.936 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Ziprasidone (marketed as Geodon among others) is a medication of the atypical antipsychotic type. It is used for the treatment of schizophrenia as well as acute mania and mixed states associated with bipolar disorder.[3] Its intramuscular injection form is approved for acute agitation in people with schizophrenia. Ziprasidone is also used off-label for depression, bipolar maintenance, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[4]

The by mouth form of ziprasidone is the hydrochloride salt, ziprasidone hydrochloride. The intramuscular form, on the other hand, is the mesylate salt, ziprasidone mesylate trihydrate, and is provided as a lyophilized powder. Ziprasidone gained approval in the United States on February 5, 2001.[5][6]

Medical uses

Ziprazidone is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of schizophrenia as well as acute mania and mixed states associated with bipolar disorder. Its intramuscular injection form is approved for acute agitation in schizophrenic patients for whom treatment with just ziprasidone is appropriate.[7]

In a 2013 study in a comparison of 15 antipsychotic drugs in effectivity in treating schizophrenic symptoms, ziprasidone demonstrated low-medium effectivity. Less effective than clozapine, slightly less effective than haloperidol, quetiapine, and aripiprazole, approximately as effective as chlorpromazine, and slightly more effective than lurasidone.[8] Ziprasidone is effective in the treatment of schizophrenia, though evidence from the CATIE trials suggests it is less effective than olanzapine, and equally as effective compared to quetiapine. There are higher discontinuation rates for lower doses of Ziprasidone, which are also less effective than higher doses.[9]

Discontinuation

The British National Formulary recommends a gradual withdrawal when discontinuing antipsychotic treatment to avoid acute withdrawal syndrome or rapid relapse.[10]

Adverse effects

Ziprasidone received a black box warning due to increased mortality in elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis.[11]

Sleepiness and headache are very common adverse effects (>10%).[12][13]

Common adverse effects (1–10%), include producing too much saliva or having dry mouth, runny nose, respiratory disorders or coughing, nausea and vomiting, stomach aches, constipation or diarrhea, loss of appetite, weight gain (but the smallest risk for weight gain compared to other antipsychotics[14]), rashes, fast heart beats, blood pressure falling when standing up quickly, muscle pain, weakness, twitches, dizziness, and anxiety.[12][13] Extrapyramidal symptoms are also common and include tremor, dystonia (sustained or repetitive muscle contractions), akathisia (the feeling of a need to be in motion), parkinsonism, and muscle rigidity; in a 2013 meta-analysis of 15 antipsychotic drugs, ziprasidone ranked 8th for such side effects.[15]

Ziprasidone is known to cause activation into mania in some bipolar patients.[16][17][18]

This medication can cause birth defects, according to animal studies, although this side effect has not been confirmed in humans.[11]

Recently, the FDA required the manufacturers of some atypical antipsychotics to include a warning about the risk of hyperglycemia and Type II diabetes with atypical antipsychotics. Some evidence suggests that ziprasidone does not cause insulin resistance to the degree of other atypical antipsychotics, such as Zyprexa. Weight gain is also less of a concern with Ziprasidone compared to other atypical antipsychotics.[19][20][21][22] In fact, in a trial of long term therapy with ziprasidone, overweight patients (BMI > 27) actually had a mean weight loss overall.[11] According to the manufacturer insert, ziprasidone caused an average weight gain of 2.2 kg (4.8 lbs), which is significantly lower than other atypical antipsychotics, making this medication better for patients that are concerned about their weight. In December 2014, the FDA warned that ziprasidone could cause a potentially fatal skin reaction, Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms, although this was believed to occur only rarely.[23]

Pharmacology

Ziprasidone is a full antagonist of D2 receptors and of 5-HT2A receptors and is a partial agonist of 5-HT1A receptors and a partial antagonist of 5-HT2C receptors and 5-HT1D receptors.[1]

Ziprasidone acts as an antagonist/inverse agonist (unless otherwise noted) of the following receptors and transporters:[24][25][26][27][28]

- 5-HT1A receptor (Ki = 12 nM) (partial agonist)[29]

- 5-HT1B receptor (Ki = 4.0 nM) (partial agonist)[30]

- 5-HT1D receptor (Ki = 2.3 nM)

- 5-HT2A receptor (Ki = 0.6 nM)

- 5-HT2C receptor (Ki = 13 nM)

- 5-HT6 receptor (Ki = 61 nM)

- 5-HT7 receptor (Ki = 6 nM)

- D1 receptor (Ki = 30 nM)

- D2 receptor (Ki = 6.8 nM)

- D3 receptor (Ki = 7.2 nM)

- α1A-adrenergic receptor (Ki = 18 nM)

- α2A-adrenergic receptor (Ki = 160 nM)

- H1 receptor (Ki = 63 nM)

- 5-HT transporter (Ki = 53 nM) (inhibitor)[31]

- NE transporter (Ki = 48 nM) (inhibitor)[31]

Correspondence to clinical effects

Ziprasidone's affinities for most of the dopamine and serotonin receptors and the α1-adrenergic receptor are high and its affinity for the histamine H1 receptor is moderate.[24][32] It also displays some inhibition of synaptic reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine, though not dopamine.[24][33]

Ziprasidone's efficacy in treating the positive symptoms of schizophrenia is believed to be mediated primarily via antagonism of the dopamine receptors, specifically D2. Blockade of the 5-HT2A receptor may also play a role in its effectiveness against positive symptoms, though the significance of this property in antipsychotic drugs is still debated among researchers.[34] Blockade of 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C and activation of 5-HT1A as well as inhibition of the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine may all contribute to its ability to alleviate negative symptoms.[35] The relatively weak antagonistic actions of ziprasidone on the α1-adrenergic receptor likely in part explains some of its side effects, such as orthostatic hypotension. Unlike many other antipsychotics, ziprasidone has no significant affinity for the mACh receptors, and as such lacks any anticholinergic side effects. Like most other antipsychotics, ziprasidone is sedating due primarily to serotonin and dopamine blockade.[36][37]

Pharmacokinetics

The systemic bioavailability of ziprasidone is 100% when administered intramuscularly and 60% when administered orally without food.[1]

After a single dose intramuscular administration, the peak serum concentration typically occurs at about 60 minutes after the dose is administered, or earlier.[38] Steady state plasma concentrations are achieved within one to three days. Exposure increases in a dose-related manner and following three days of intramuscular dosing, little accumulation is observed.

Ziprasidone absorption is optimally achieved when administered with food. Without a meal preceding dose, the bioavailability of the drug is reduced by approximately 50%.[11][39]

Ziprasidone is hepatically metabolized by aldehyde oxidase; minor metabolism occurs via cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4).[40] Medications that induce (e.g. carbamazepine) or inhibit (e.g. ketoconazole) CYP3A4 have been shown to decrease and increase, respectively, blood levels of ziprasidone.[41][42]

Its biological half-life time is 10 hours at doses of 80-120 milligrams.[2]

Society and culture

Lawsuit

In September 2009, the U.S. Justice Department announced that Pfizer had been ordered to pay an historic fine of $2.3 billion as a penalty for fraudulent marketing of several drugs, including Geodon.[43] Pfizer had illegally promoted Geodon and caused false claims to be submitted to government health care programs for uses that were not medically accepted indications. The civil settlement also resolves allegations that Pfizer paid kickbacks to health care providers to induce them to prescribe Geodon, as well as other drugs. This was the largest civil fraud settlement in history against a pharmaceutical company.

History

Ziprasidone is a structural analogue of Risperidone.[44] Ziprasidone is similar chemically to Risperidone.[45] In 1987,[46] Ziprasidone was first synthesized on the Pfizer central research campus in Groton, Connecticut.[47]

Phase I trials started in 1995.[48] In 1998 ziprasidone was approved in Sweden.[49][50] After the FDA raised concerns about long QT syndrome, more clinical trials were conducted and submitted to the FDA, which approved the drug on February 5, 2001.[48][51][52]

References

- 1 2 3 Stahl; Chiara Mattei; Maria Paola Rapagnani (February 2011). "Ziprasidone Hydrocloride: What Role in the Management of Schizophrenia?". Journal of Central Nervous System Disease. 3: 1. PMC 3663608

. PMID 23861634. doi:10.4137/JCNSD.S4138.

. PMID 23861634. doi:10.4137/JCNSD.S4138. - 1 2 Nicolson, SE; Nemeroff, CB (December 2007). "Ziprasidone in the treatment of mania in bipolar disorder.". Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 3 (6): 823–34. PMC 2656324

. PMID 19300617.

. PMID 19300617. - ↑ "Geodon". Drugs.com. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ Poole, Jerod. "Geodon Approved Uses". CrazyMeds. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- ↑ http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/pfizer-to-launch-zeldox-in-9-european-union-countries-beginning-next-month-76154202.html

- ↑ http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2001/20-825_geodan.cfm

- ↑ "Pfizer to pay $2.3 billion to resolve criminal and civil health care liability relating to fraudulent marketing and the payment of kickbacks". Stop Medicare Fraud, US Dept of Health & Human Svc, and of US Dept of Justice. Retrieved 2012-07-04.

- ↑ Leucht, Stefan; Cipriani, Andrea; Spineli, Loukia; Mavridis, Dimitris; Örey, Deniz; Richter, Franziska; Samara, Myrto; Barbui, Corrado; Engel, Rolf R; Geddes, John R; Kissling, Werner; Stapf, Marko Paul; Lässig, Bettina; Salanti, Georgia; Davis, John M (September 2013). "Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis". The Lancet. 382 (9896): 951–962. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3.

- ↑ Citrome, L; Yang, R; Glue, P; Karayal, ON (June 2009). "Effect of ziprasidone dose on all-cause discontinuation rates in acute schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: a post-hoc analysis of 4 fixed-dose randomized clinical trials.". Schizophrenia Research. 111 (1–3): 39–45. PMID 19375893. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2009.03.009.

- ↑ Group, BMJ, ed. (March 2009). "4.2.1". British National Formulary (57 ed.). United Kingdom: Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. p. 192. ISSN 0260-535X.

Withdrawal of antipsychotic drugs after long-term therapy should always be gradual and closely monitored to avoid the risk of acute withdrawal syndromes or rapid relapse.

- 1 2 3 4 "Geodon Prescribing Information" (PDF). Pfizer, Inc. Retrieved 2009-01-26.

- 1 2 "Product Information: Zeldox IM (ziprasidone mesilate)". Australia Therapeutic Goods Administration. February 24, 2016.

- 1 2 "Product Information: Zeldox (ziprasidone hydrochloride)". Australia Therapeutic Goods Administration. February 24, 2016.

- ↑ FDA Psychopharmacological Drugs Advisory Committee (July 19, 2000). "Briefing Document for Zeldoz Capsules" (PDF). FDA.

- ↑ Leucht, S; et al. (2013). "Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis". The Lancet. 382: 951–962. PMID 23810019. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3.

- ↑ Baldassano CF, Ballas C, Datto SM, et al. (February 2003). "Ziprasidone-associated mania: a case series and review of the mechanism". Bipolar Disorders. 5 (1): 72–5. PMID 12656943. doi:10.1034/j.1399-5618.2003.02258.x.

- ↑ Keating AM, Aoun SL, Dean CE (2005). "Ziprasidone-associated mania: a review and report of 2 additional cases". Clinical Neuropharmacology. 28 (2): 83–6. PMID 15795551. doi:10.1097/01.wnf.0000159952.64640.28.

- ↑ Davis R, Risch SC (April 2002). "Ziprasidone induction of hypomania in depression?". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 159 (4): 673–4. PMID 11925314. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.4.673.

- ↑ Tschoner A, Engl J, Rettenbacher M, et al. (January 2009). "Effects of six-second generation antipsychotics on body weight and metabolism – risk assessment and results from a prospective study". Pharmacopsychiatry. 42 (1): 29–34. PMID 19153944. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1100425.

- ↑ Guo JJ, Keck PE, Corey-Lisle PK, et al. (January 2007). "Risk of diabetes mellitus associated with atypical antipsychotic use among Medicaid patients with bipolar disorder: a nested case-control study". Pharmacotherapy. 27 (1): 27–35. PMID 17192159. doi:10.1592/phco.27.1.27.

- ↑ Sacher J, Mossaheb N, Spindelegger C, et al. (June 2008). "Effects of olanzapine and ziprasidone on glucose tolerance in healthy volunteers". Neuropsychopharmacology. 33 (7): 1633–41. PMID 17712347. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1301541.

- ↑ Newcomer JW (2005). "Second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics and metabolic effects: a comprehensive literature review". CNS Drugs. 19 Suppl 1: 1–93. PMID 15998156. doi:10.2165/00023210-200519001-00001.

- ↑ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA reporting mental health drug ziprasidone (Geodon) associated with rare but potentially fatal skin reactions". FDA. December 11, 2014. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Hagop S. Akiskal; Mauricio Tohen (June 24, 2011). Bipolar Psychopharmacotherapy: Caring for the Patient. John Wiley & Sons. p. 209. ISBN 978-1-119-95664-8. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- ↑ Seeger TF, Seymour PA, Schmidt AW, et al. (October 1995). "Ziprasidone (CP-88,059): a new antipsychotic with combined dopamine and serotonin receptor antagonist activity". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 275 (1): 101–13. PMID 7562537.

- ↑ Schotte A, Janssen PF, Gommeren W, et al. (March 1996). "Risperidone compared with new and reference antipsychotic drugs: in vitro and in vivo receptor binding". Psychopharmacology. 124 (1–2): 57–73. PMID 8935801. doi:10.1007/bf02245606.

- ↑ "PDSP Database – UNC". Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- ↑ Brunton, Laurence (2011). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics 12th Edition. China: McGraw-Hill. pp. 406–410. ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8.

- ↑ Newman-Tancredi A, Gavaudan S, Conte C, et al. (August 1998). "Agonist and antagonist actions of antipsychotic agents at 5-HT1A receptors: a [35S]GTPgammaS binding study". European Journal of Pharmacology. 355 (2–3): 245–56. PMID 9760039. doi:10.1016/S0014-2999(98)00483-X.

- ↑ Roland Seifert; Thomas Wieland; Raimund Mannhold; Hugo Kubinyi; Gerd Folkers (July 17, 2006). G Protein-Coupled Receptors as Drug Targets: Analysis of Activation and Constitutive Activity. John Wiley & Sons. p. 227. ISBN 978-3-527-60695-5. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- 1 2 Daniel DG, Zimbroff DL, Potkin SG, Reeves KR, Harrigan EP, Lakshminarayanan M (May 1999). "Ziprasidone 80 mg/day and 160 mg/day in the acute exacerbation of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: a 6-week placebo-controlled trial. Ziprasidone Study Group". Neuropsychopharmacology. 20 (5): 491–505. PMID 10192829. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00090-6.

- ↑ Nemeroff CB, Lieberman JA, Weiden PJ, et al. (November 2005). "From clinical research to clinical practice: a 4-year review of ziprasidone". CNS Spectrums. 10 (11 Suppl 17): 1–20. PMID 16381088.

- ↑ Tatsumi M, Jansen K, Blakely RD, Richelson E (March 1999). "Pharmacological profile of neuroleptics at human monoamine transporters". European Journal of Pharmacology. 368 (2–3): 277–83. PMID 10193665. doi:10.1016/S0014-2999(99)00005-9.

- ↑ Heinz Lüllmann; Klaus Mohr (2006). Pharmakologie und Toxikologie: Arzneimittelwirkungen verstehen- Medikamente gezielt einsetzen; ein Lehrbuch für Studierende der Medizin, der Pharmazie und der Biowissenschaften, eine Informationsquelle für Ärzte, Apotheker und Gesundheitspolitiker. Georg Thieme Verlag. ISBN 978-3-13-368516-0. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- ↑ Alan F. Schatzberg; Charles B. Nemeroff (February 10, 2006). Essentials of Clinical Psychopharmacology. American Psychiatric Pub. p. 297. ISBN 978-1-58562-243-6. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- ↑ Monti JM (March 2010). "Serotonin 5-HT(2A) receptor antagonists in the treatment of insomnia: present status and future prospects.". Drugs Today. 46: 183–93. PMID 20467592. doi:10.1358/dot.2010.46.3.1437247.

- ↑ Salmi P, Ahlenius S (April 2000). "Sedative effects of the dopamine D1 receptor agonist A 68930 on rat open-field behavior.". NeuroReport. 11: 1269–72. PMID 10817605. doi:10.1097/00001756-200004270-00025.

- ↑ "Ziprasidone (Professional Patient Advice)". Drugs.com. Retrieved 2016-02-02.

- ↑ Miceli JJ, Glue P, Alderman J, Wilner K (2007). "The effect of food on the absorption of oral ziprasidone". Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 40 (3): 58–68. PMID 18007569.

- ↑ Sandson NB, Armstrong SC, Cozza KL (2005). "An overview of psychotropic drug-drug interactions". Psychosomatics. 46 (5): 464–94. PMID 16145193. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.46.5.464.

- ↑ Miceli JJ, Anziano RJ, Robarge L, Hansen RA, Laurent A (2000). "The effect of carbamazepine on the steady-state pharmacokinetics of ziprasidone in healthy volunteers". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 49 Suppl 1: 65S–70S. PMC 2015057

. PMID 10771457. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.2000.00157.x.

. PMID 10771457. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.2000.00157.x. - ↑ Miceli JJ, Smith M, Robarge L, Morse T, Laurent A (2000). "The effects of ketoconazole on ziprasidone pharmacokinetics—a placebo-controlled crossover study in healthy volunteers". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 49 Suppl 1: 71S–76S. PMC 2015056

. PMID 10771458. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.2000.00156.x.

. PMID 10771458. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.2000.00156.x. - ↑ "Justice Department Announces Largest Health Care Fraud Settlement in Its History". justice.gov. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1324958/

- ↑ https://books.google.se/books?id=Sd6ot9ul-bUC&pg=PA465&lpg=PA465&dq=#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ↑ http://austinpublishinggroup.com/schizophrenia/download.php?file=fulltext/schizophrenia-v3-id1027.pdf

- ↑ Newcomer, John W.; Fallucco, Elise M. (2009). "Ziprasidone". In Schatzberg, Alan F.; Nemeroff, Charles B. The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of psychopharmacology (4th ed.). Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Pub. p. 641. ISBN 9781585623099.

- 1 2 "Approval Package For: Application Number 20-919" (PDF). FDA Center For Drug Evaluation And Research. May 26, 1998.

- ↑ "First Approval For Pfizer's Zeldoxs". The Pharma Letter. Retrieved October 15, 2016.

- ↑ Letter, The Pharma. "Pfizer's Zeldox approvable in USA – Pharmaceutical industry news". thepharmaletter.com. Retrieved October 15, 2016.

- ↑ "FDA Background On ZeldoxTM (ziprasidone hydrochloride capsules) Pfizer, Inc. PsychoPharmacological Drugs Advisory Committee" (PDF). FDA. July 19, 2000.

- ↑ Inc, Pfizer. "Pfizer to Launch Zeldox in 9 European Union Countries Beginning Next Month". prnewswire.com. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

Further reading

- David Taylor (2006). Schizophrenia in Focus. Pharmaceutical Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-85369-607-0. Retrieved May 13, 2012.