World War II persecution of Serbs

| World War II Persecution of Serbs or Serbian Genocide | |

|---|---|

| Part of World War II | |

Serbs, expelled from their homes in the Independent State of Croatia, march out of town carrying large bundles. | |

| Location |

|

| Date | 1941–45 |

| Target | Serbs |

Attack type |

Mass murder Ethnic cleansing Deportation Forced conversion |

| Deaths | Estimates vary and are disputed. It is agreed that the total number of Serbian deaths ranges from 300,000 to 500,000, while the total number of Serbs killed in concentration camps is estimated to be around 100,000[1][2] |

| Perpetrators | Ustaše government of the Independent State of Croatia,[3][4] Albanian collaborationists,[5][6] Axis occupation forces[7] |

| Motive | Racial laws that also caused The Holocaust in Croatia and the Porajmos |

The World War II persecution of Serbs includes the extermination, expulsion and forced religious conversion of large numbers of ethnic Serbs by the Ustaše regime in the Independent State of Croatia (NDH), as well as killings and expulsions of Serbs by the various Axis forces and their local quislings in occupied Yugoslavia during World War II. The persecution of Serbs by the Ustaše regime is also known as the Serbian genocide.[8][9][10][11][12][13][14]

The number of Serbs murdered by the Ustaše is the subject of much debate and estimates vary widely. Yad Vashem estimates over 500,000 murdered, 250,000 expelled and 200,000 forcibly converted to Catholicism.[15] The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum has estimated that Ustaša authorities murdered between 320,000 and 340,000 ethnic Serb residents of Croatia and Bosnia between 1941-45 (the period of Ustaše control), of whom between 45,000 and 52,000 were murdered at the Jasenovac concentration camp alone.[16] According to the Federal Institute for Statistics in Belgrade, the "actual" figure of the casualties suffered within Yugoslavia's border of war-related causes during the second world war was ca. 597,323 deaths. Of these, 346,740 were Serbs and 83,257 were Croats.[17]

Background

Croatian ultranationalism

In April 1941, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was invaded by the Axis powers, and the puppet state known as the Independent State of Croatia (NDH) was created, ruled by the Ustaše regime. The ideology of the Ustaše movement was a blend of Nazism,[18] Roman Catholicism, and Croatian ultranationalism. The Ustaše supported the creation of a Greater Croatia that would span to the Drina river and the outskirts of Belgrade.[19] The movement emphasized the need for a racially "pure" Croatia and promoted the extermination of Serbs, Jews[20] and Gypsies.[21]

A major ideological influence on the Croatian nationalism of the Ustaše was the 19th-century nationalist Ante Starčević.[21] Starčević was an advocate of Croatian unity and independence and was both anti-Habsburg and anti-Serb.[21] He envisioned the creation of a Greater Croatia that would include territories inhabited by Bosniaks, Serbs, and Slovenes, considering Bosniaks and Serbs to be Croats who had been converted to Islam and Orthodox Christianity and considering the Slovenes to be "mountain Croats".[21] Starčević argued that the large Serb presence in the territories that were claimed by a Greater Croatia was the result of recent settlement, which had been encouraged by the Habsburg rulers, along with the influx of groups like Vlachs who took up Orthodox Christianity and identified themselves as Serbs.[22] The Ustaše used Starčević's theories to promote the annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina to Croatia and they recognized Croatia as having two major ethnocultural components: Catholic Croats and Muslim Croats,[23] because the Ustaše saw the Islam of the Bosnian-Muslims as a religion which "keeps true the blood of Croats."[23] Armed struggle, genocide and terrorism were glorified by the group.[24]

Independent State of Croatia

After Nazi forces entered into Zagreb on April 10, 1941 Pavelić's closest associate Slavko Kvaternik proclaimed the formation of the Independent State of Croatia on a Radio Zagreb broadcast. Meanwhile, Pavelić and several hundred Ustaše volunteers left their camps in Italy and travelled to Zagreb, where Pavelić declared a new government on 16 April 1941.[25] He accorded himself the title of "Poglavnik" (German: Führer, English: Chief leader). The Independent State of Croatia was declared to be on Croatian "ethnic and historical territory".[26]

This country can only be a Croatian country, and there is no method we would hesitate to use in order to make it truly Croatian and cleanse it of Serbs, who have for centuries endangered us and who will endanger us again if they are given the opportunity.— Milovan Žanić, the minister of the NDH Legislative council, on 2 May 1941, [27]

Jasenovac concentration camp

_used_in_Croatia_-_1941%E2%80%931945.jpg)

A large portion of the atrocities occurred in the notorious Jasenovac concentration camp. It was the largest extermination camp in the Balkans.[7] The Ustaše interned, tortured and brutally executed men, women and children in the camp. Serbs constituted the majority of inmates.[3][7]

Upon arrival at the camp, the prisoners were marked with colors, similar to the use of Nazi concentration camp badges: blue for Serbs, and red for communists (non-Serbian resistance members and/or Communists), while Roma had no marks. In several instances, inmates with blue badges were murdered immediately upon arrival.[28] Serbs were predominantly brought from the Kozara region, where the Ustaše captured areas formerly held by Partisans.[29] These were brought to the camp without sentence, most destined for immediate execution, accelerated via the use of machine-guns.[30]

Aside from sporadic and random killings and deaths due to the poor living conditions, many inmates arriving at Jasenovac were scheduled for systematic extermination. An important criterion for selection was the duration of a prisoner's anticipated detention. Strong men capable of labor and sentenced to less than three years of incarceration were allowed to live. All inmates with indeterminate sentences or sentences of three years or more were immediately scheduled for execution, regardless of fitness.[31]

The so-called "manual-means-of-execution", the Ustaše's favorites, were executions that took part in utilizing sharp or blunt craftsmen tools: knives, saws, hammers, etc. The preferred manual-weapon of many Ustaše guards was the Srbosjek (or Serbcutter). This knife was originally a type of agricultural knife manufactured for wheat sheaf cutting.[32] The upper part of the knife was made of leather, as a sort of a glove, designed to be worn with the thumb going through the hole, so that only the blade protruded from the hand. It was a curved, 12 cm long knife with the edge on its concave side. The knife was fastened to a bowed oval copper plate, while the plate was fastened to a thick leather bangle.[33]

These mass-executions took place at various locations. *At the "Granik" ramp, by the Sava, internees were hung by a crane, had their intestines and necks slashed, then were thrown into the river after being hit by blunt tools in the head. Later, inmates were tied in pairs, slashed in the stomach and thrown into the river while still alive.[34]

- In the vicinity of Donja Gradina, empty areas were encircled with wire and used for slaughter. The victims were slain with knives, or had their skulls smashed with mallets. The memorial site includes 117 acres and 105 mass graves.[35]

- Mlaka and Jablanac were two sites used as collection and labor camps for the women and children in camps III and V, but also as places where many of these women and children, as well as other groups, were executed at the bank of the Sava river, between the two locations.

- At Velika Kustarica, as many as 50,000 people were killed during the 1941–42 winter.[36]

There were throat-cutting contests of Serbs, in which prison guards made bets among themselves as to who could slaughter the most inmates. It was reported that guard and former Franciscan priest Petar Brzica won a contest on 29 August 1942 after cutting the throats of 1,360 inmates.[37] A gold watch, a silver service, a roasted suckling pig and a bottle of Italian wine were among his rewards.[38] Others who confessed to participating in the bet included Ante Zrinušić, who killed some 600 inmates, and Mile Friganović, who gave a detailed and consistent report of the incident. Friganović admitted to having killed some 1,100 inmates. He specifically recounted his torture of an old man, known as "Vukašin"; he attempted to compel the man to bless Ante Pavelić, which the old man refused to do, even after Friganović had cut off his ears, nose and tongue after each refusal. Ultimately, he cut out the old man's eyes, tore out his heart, and slashed his throat.

In April 1945, as Partisan units approached the camp, the camp's supervisors attempted to erase traces of the atrocities by working the death camp at full capacity. On 22 April, 600 prisoners revolted; 520 were killed and 80 escaped.[39] Before abandoning the camp shortly after the prisoner revolt, the Ustaše killed the remaining prisoners and torched the buildings, guardhouses, torture rooms, the "Picilli Furnace", and all the other structures in the camp, apparently in an effort to make the number of victims impossible to definitively ascertain. Upon entering the camp, the Partisans found only ruins, soot, smoke, and the skeletal remains of thousands of victims.

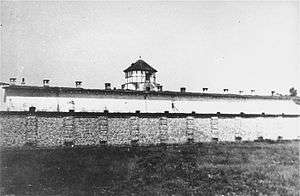

Stara Gradiška concentration camp

The Stara Gradiška concentration camp was built on the site of the Stara Gradiška prison. The camp was specially constructed for women and children[40] and it became notorious for the crimes which were committed against them. The camp was guarded by the Ustaše and several female Croatian nurses. Inmates were killed using different means, including firearms, mallets, machetes and knives. At the "K", or "Kula" unit, Jewish and Serbian women, with weak or little children, were starved and tortured at the "Gagro Hotel", a cellar which an Ustaša named Nikola Gagro used as a place of torture.[41]

Other inmates were killed using poisonous gas. The first to be gassed were the women and children who arrived from camp Djakovo with gas vans that Šimo Klaić called "green Thomas". The method was later replaced by stationary gas-chambers where inmates were killed with Zyklon B and sulfur dioxide.[42]

Gas experiments were initially conducted in veterinary stables near the "Economy" unit, where horses and then humans were killed with sulphur dioxide and later they were killed with Zyklon B. Gassing was tested on children in the yard, where the camp commandant, Ustaša sergeant Ante Vrban, viewed its effects. Most gassing deaths occurred in the attics of "the infamous tower", where several thousand children from the Kožara region were killed in May, and 2,000 more were killed in June 1942.[43][44][45] Subsequently, smaller groups of 400-600 children, and a few men and women, were gassed.[46]

Sisak children's concentration camp

At Sisak, near Jasenovac, the Ustaše presence was vigilant. Early in 1942, the local synagogue was vandalized and looted by Croats, and the building was later transformed to house a worker's hall.[47] The inhabitants of Sisak were quickly brought to the Ustaše's attention, and those of Serb or other non-Croat descent were tormented.[48]

A large camp was later erected and it held more than 6,600 Serb and Roma children throughout World War II. The children, aged between 3 and 16, were housed in abandoned stables, ridden with filth and pests. Malnutrition and dysentery seriously impaired their health. They were fed daily with a portion of thin gruel and treated horribly by their captors.[49]

Jastrebarsko concentration camp

The camp housed Serb children between the ages of one month to fourteen years[50] and was operational for two months in 1942. The camp was set up specifically for Serb children from the Kozara region of Croatia. During its two months of operation, 1,018 children died in the camp. Franjo Ilovar, a grave digger who was paid "per piece", claimed to have buried 768 children in a six-week period.[51] Another 1,300 children were transported to Jasenovac. On 26 August 1942, the Yugoslav Partisans liberated the camp, freeing approximately 700 children.

Jadovno concentration camp

The Jadovno concentration camp was located in а valley near Mount Velebit. It occupied an area of 1250 square meters and was fenced with barbed wire 4 metres high. The guards were posted 1 km all around the camp's barbed wire. Prisoners, mostly Serbs, arrived from the town of Gospić where the Ustaše selected their victims. The Jadovno Victims Association has stated that in 132 days in the camp 40,123 victims were killed. Among them 38,010 were Serbs, 1,998 were Jews, 88 Croats, 11 Slovenes, 9 Muslims, 2 Hungarians, 2 Czechs, 1 Russian, 1 Roma and 1 Montenegrin.[52]

Atrocities

The atrocities committed by the Ustaše stunned many observers. Brigadier Sir Fitzroy Maclean, Chief of the British military mission to the Partisans commented,

Some Ustaše collected the eyes of Serbs they had killed, sending them, when they had enough, to the Poglavnik ... for his inspection or proudly displaying them and other human organs in the cafés of Zagreb.[53]

The Ustaše also cremated living inmates, who were sometimes drugged and sometimes fully awake, as well as corpses. The first cremations took place in the brick factory ovens in January 1942.[54] Engineer Hinko Dominik Picilli perfected this method by converting seven of the kiln's furnace chambers into more sophisticated crematories.[55][56] Some bodies were buried rather than cremated, however, and they were exhumed after the war.

A large number of massacres were committed. The most notable ones were:

- Gudovac massacre — 184–196 Serbs were massacred by the Ustaše.[57]

- Glina massacre — 260 Serbs were herded into a church and killed by gunfire.[58] Those who had converted to Roman Catholicism were spared on that occasion.[59]

- Javor massacre — Hundreds of Serbs were murdered in Javor, near Srebrenica, and Ozren.[60]

- Korita massacre — 176 Serbs were massacred and their bodies were thrown into a pit called the Koritska Jama.[61]

- Kosinj massacre — Approximately 600 Serbs were massacred by the Ustaše.[62]

- Metković massacre — 280 Serbs were massacred by the Ustaše in Metković on 25 June 1941.[63]

- Otočac massacre — 331 Serbs were massacred by the Ustaše, including a Serbian Orthodox priest who was forced to convert to Roman Catholicism before his heart was cut out of his chest.[64]

- Prebilovci massacre — Approximately 650 Serbs were murdered by the Ustaše.[65]

Religious persecution

The Ustaše recognized both Roman Catholicism and Islam as the national religions of Croatia, but they held the position that Eastern Orthodoxy, as a symbol of Serbian identity, was their foe.[66] They never recognized the existence of the Serb people on Croatian territory or anywhere else in the world, for that matter – they referred to them only as "Croats of the Eastern faith", also referring to Bosnian-Muslims (or Bosniaks) as "Croats of the Islamic faith". While they were in power, the Ustaše banned the use of the expression "Serbian Orthodox faith" and they mandated the use of the expression "Greek-Eastern faith" in its place.[57] Some 250,000 Serbs were converted to Roman Catholicism in a six-month-period in 1941.[67] Hundreds of Serbian Orthodox churches were closed, destroyed, or plundered during Ustaše rule.[57] On 2 July 1942, the Croatian Orthodox Church was founded in order to replace the institutions of the Serbian Orthodox Church.[68]

Expulsion

In a six-month period in 1941, some 120,000 Serbs were expelled to Nazi-occupied Serbia, and tens of thousands fled.[67] The general plan was to have prominent people deported first, so their property could be nationalized and the remaining Serbs could then be more easily manipulated. By the end of September 1941, about half of the Serbian Orthodox clergy, 335 priests, had been expelled.[69]

Linguistic discrimination

In 1941, the Nazi puppet Independent State of Croatia banned the use of the Cyrillic script,[70] having regulated it on 25 April 1941,[71] and in June 1941 it began eliminating "Eastern" (Serbian) words from the Croatian language, and shut down Serbian schools.[72][73] Ante Pavelić ordered, through the "Croatian state office for language", the creation of new words from old roots (some which are used today), and purged many Serbian words.[74]

Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia

- Kragujevac massacre. Between 18–21 October 1941, men and boys were rounded up by German soldiers and members of the Serbian Volunteer Command from the vicinity of Kragujevac, Serbia. All males from the town between the ages of sixteen and sixty were assembled, including high school students; 2,778 were shot.[75] The massacre was a direct reprisal for German losses in a battle with Partisans and Chetniks in early October.[76] The German High Command decided, based on reports that bodies had been mutilated by the guerrillas, that the punishment must be particularly harsh. A German report stated, "The executions in Kragujevac occurred although there had been no attacks on members of the Wehrmacht in this city, for the reason that not enough hostages could be found elsewhere."[77][78]

- 1942 raid in southern Bačka. The most notable war crime during the occupation was the mass murder of the civilians, mostly of Serb and Jewish ethnicity, carried out by Hungarian Axis troops in January 1942 raid in southern Bačka. The total number of civilians killed in the raid was 3,808. Locations that were affected by the raid included Novi Sad, Bečej, Vilovo, Gardinovci, Gospođinci, Đurđevo, Žabalj, Lok, Mošorin, Srbobran, Temerin, Titel, Čurug and Šajkaš.[79]

During the four years of occupation of Vojvodina, the Axis forces committed numerous war crimes against the civilian population: about 50,000 people in Vojvodina were murdered and about 280,000 were arrested, violated or tortured.[80] The victims belonged to several ethnic groups that lived in Vojvodina, but the largest number of victims were of Serb, Jewish and Romani ethnicity.[81]

Albanian role and Kosovo

Galeazzo Ciano, Mussolini's son-in-law, the Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs, speaking of Albanian claims to Kosovo as valuable to Italy's objectives.[82]

During World War II, with the fall of Yugoslavia in 1941, the Italians placed the land inhabited by ethnic Albanians under the jurisdiction of an Albanian quisling government, including Kosovo, whose inclusion into a geo-political Albanian entity was followed by extensive persecution of non-Albanians (mostly Serbs) by Albanian fascists. Most of the war crimes were perpetrated by the 21st Waffen Mountain Division of the SS Skanderbeg (1st Albanian) and the Balli Kombëtar.[83]

Mustafa Kruja, the then Prime Minister of Albania, June 1942.[84][85]

In September 1943, Italy, which had occupied Albania, surrendered to the Allies and shortly afterwards, the Germans occupied Greater Albania, and most Italian soldiers in the country surrendered to the Germans.[86] Xhafer Deva, an ally of the Germans in the region,[87] began recruiting Kosovo Albanians to join the Waffen-SS.[88] The 21st Waffen Mountain Division of the SS Skanderbeg (1st Albanian) was formed on 1 May 1944.[89] Composed of ethnic Albanians, it was named after Albanian national hero George Kastrioti Skanderbeg, who fought the Ottoman Turks in the 15th century.[90] The division had a strength of 6,500 men at the time of its creation[91] and was better known for murdering, raping, and looting in predominantly Serbian areas than for participating in combat operations on behalf of the German war effort.[92] With the Allied victory in the Balkans imminent, Deva and his men attempted to purchase weapons from withdrawing German soldiers in order to organize a "final solution" of the Slavic population of Kosovo. Nothing came of this as the powerful Yugoslav Partisans prevented any large-scale ethnic cleansing of Slavs from occurring.[93]

In April 1943, Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler created the 21st SS Division manned by Albanian and Kosovar Albanian volunteers. From August 1944, the division participated in operations against the Yugoslav Partisans and in massacring local Serbs.[94] SS-Brigadeführer August Schmidthuber, one of the commanders of the division, was captured in 1945 and turned over to Yugoslav authorities. Schmidthuber was put on trial in February 1947 by a Yugoslav military tribunal in Belgrade, on charges of participating in massacres, deportations and atrocities against civilians. The tribunal sentenced him to death by hanging and he was executed on 27 February 1947.[95]

Controversy

Revisionism in modern-day Croatia

Many Croats, including politicians, have attempted to minimise the magnitude of the genocide perpetrated against Serbs in the World War II puppet state of Germany, the Independent State of Croatia.[96]

By 1989, the future President of Croatia, Franjo Tuđman (whose family had been Partisans during World War II), had embraced a radical nationalism, and published Horrors of War: Historical Reality and Philosophy, in which he questioned the official numbers of victims killed by the Ustaše during the Second World War. In his book, Tuđman claimed that fewer than thirty-thousand people died at Jasenovac.[16] Tuđman estimated that a total of 900,000 Jews had perished in the Holocaust.[97] Tuđman's views and his government's toleration of Ustaša symbols frequently strained relations with Israel.[98]

Possibly the most overt and well-known example of ultranationalist, anti-Serb sentiment in contemporary Croatian public life is Thompson, a Croatian rock band that has been protested against on numerous occasions for having sung Ustaše songs, most notably Jasenovac i Gradiška Stara. People publicly displaying Ustaše affiliations at major Thompson concerts in Croatia and elsewhere is a frequent occurrence, leading to complaints from the Simon Wiesenthal Center.[99]

In 2006, a video was leaked showing Croatian President Stipe Mesić giving a speech in Australia in the early 1990s, in which he said that the Croats had "won a great victory on April 10th" (the date of the formation of the Independent State of Croatia in 1941), and that Croatia needed to apologize to no one for Jasenovac.[100]

Revisionism in Croat diaspora

In 2008, in Melbourne, Australia, a Croat restaurant held a celebration to honour Ustaše leader Ante Pavelić. The event was an "outrageous affront both to his victims and to any persons of morality and conscience who oppose racism and genocide", Dr. Efraim Zuroff, of the Simon Wiesenthal Center, stated. According to local press reports, a large photograph of Pavelić was hung in the restaurant, T-shirts with his picture and that of two other commanders in the 1941–45 Ustaše government were offered for sale at the bar, and the establishment of the Independent State of Croatia was celebrated. Zuroff noted this was not the first time that Croatian émigrés in Australia had openly defended Croat Nazi war criminals.

It is high time that the authorities in Australia find a way to take the necessary measures to stop such celebrations, which clearly constitute racist, ethnic, and anti-Semitic incitement against Serbs, Jews, and Gypsies.[101]

Position of the Roman Catholic Church

Mile Budak, 13 July 1941.[102]

For the duration of the war, the Vatican kept full diplomatic relations with the Independent State of Croatia and granted Pavelić an audience with its papal nuncio in the capital Zagreb, albeit not an official diplomatic meeting. The nuncio was briefed on the efforts of the Ustaše to convert ethnic-Serbs to Catholicism. Some former priests, mostly Franciscans, particularly in, but not limited to, Herzegovina and Bosnia, took part in the atrocities themselves. Miroslav Filipović was a Franciscan friar (from the Petrićevac monastery) who joined the Ustaše on 7 February 1942 in a brutal massacre of 2,730 Serbs of the nearby villages, including 500 children. He was reportedly subsequently dismissed from his order. He became the Chief Guard of the Jasenovac concentration camp where he was nicknamed "Fra Sotona" ("Friar Satan"). When he was hanged for war crimes, he wore his clerical garb, although some claim he had been defrocked.[103]

Ustaše gold

The Ustaše had sent large amounts of gold that it had plundered from Serbian and Jewish property owners during World War II into Swiss bank accounts. Of a total of 350 million Swiss Francs, about 150 million was seized by British troops; however, the remaining 200 million (ca. 47 million dollars) reached the Vatican. In October 1946, the American intelligence agency SSU alleged that these funds are still held in the Vatican Bank. This matter is the crux of a recent class action suit against the Vatican Bank and other defendants.[104]

Commemoration

The Jasenovac Memorial Museum reopened in November 2006 with a new exhibition designed by a Croatian architect, Helena Paver Njirić, and an Educational Center, designed by the firm Produkcija. The Memorial Museum features an interior of rubber-clad steel modules, video and projection screens, and glass cases displaying artifacts from the camp. Above the exhibition space, which is quite dark, is a field of glass panels inscribed with the names of the victims.

The New York City Parks Department, the Holocaust Park Committee and the Jasenovac Research Institute, with the help of then-Congressman Anthony Weiner (D-NY), established a public monument to the victims of Jasenovac in April 2005 (the sixtieth anniversary of the liberation of the camps.) The dedication ceremony was attended by ten Yugoslavian Holocaust survivors, as well as diplomats from Serbia, Bosnia and Israel. It remains the only public monument to Jasenovac victims outside the Balkans.

To commemorate the victims of the Kragujevac massacre, the whole of Šumarice, where the killings took place, was turned into a memorial park. There are several monuments there: the monument to the murdered schoolchildren and their teachers, the "Broken Wing" monument, the monument of pain and defiance and the monument "One Hundred for One", the monument of resistance and freedom. Serbian poet Desanka Maksimović wrote a poem about the massacre titled Krvava Bajka (A Bloody Fairy Tale).

Victims

Total number

Historians have had difficulty calculating and agreeing on the number of victims. The first estimates offered by the state-commission of Croatia ranged from around 500,000 to 600,000 people killed. The official estimate of the number of victims in Yugoslavia was 700,000; however, beginning in the 1990s, the Croatian side began suggesting substantially smaller numbers. The exact numbers continue to be a subject of great controversy and hot political dispute, with the Croatian government and Croatian institutions pushing for a much lower number even as recently as September 2009. The estimates vary due to lack of accurate records, the methods used for making estimates, and sometimes the political biases of the estimators. In some cases, entire families were exterminated, leaving no one to submit their names to the lists. On the other hand, it has been found that the lists include the names of people who died elsewhere, whose survival was not reported to the authorities, or who are counted more than once on the lists. The casualty figures for the whole of Yugoslavia fluctuate between the maximum 1,700,000 and such lowered figures as 1,500,000[105] or 1,000,000.[106]

An accurate total number of all those murdered at Jasenovac may never be definitively established but current estimates are around the 100,000 mark.[107][108]

Historical documentation sources

The documentation from the time of Jasenovac revolves around the different sides in the battle for Yugoslavia: The Germans, Italians and Ustaše on the one hand, and the Partisans and the Allies on the other. There are also sources originating from the documentation of the Ustaše themselves and of the Vatican. German generals issued reports of the number of victims as the war progressed. German military commanders gave different figures for the number of Serbs, Jews, and others killed by the Ustaše inside the Independent State of Croatia. They circulated figures of 400,000 Serbs (Alexander Löhr); 350,000 Serbs (Lothar Rendulic); around 300,000 (Edmund Glaise von Horstenau); in 1943; "600-700,000 until March 1944" (Ernst Fick); 700,000 (Massenbach).

Hermann Neubacher stated:

The recipe, received by the Ustaše leader and Poglavnik, the president of the Independent State of Croatia, Ante Pavelić, resembled genocidal intentions from some of the bloodiest religious wars: "A third must become Catholic, a third must leave the country, and a third must die!" This last point of the Ustaše's program was accomplished. When prominent Ustaše leaders claimed that they slaughtered a million Serbs (including babies, children, women and old men), that is, in my opinion, a boastful exaggeration. On the basis of the reports submitted to me, I believe that the number of defenseless victims slaughtered to be three-quarters of a million.

Italian soldiers reported similar figures to their commanders.[109] The Vatican's sources also cite similar figures, e.g. an example of 350,000 ethnic-Serbs slaughtered by the end of 1942 (Eugène Tisserant)[110]

Vjekoslav "Maks" Luburić, the commander-in-chief of all the Croatian camps, announced the great "efficiency" of the Jasenovac camp at a ceremony as early as 9 October 1942. During the banquet which followed, he reported with pride, obviously intoxicated: "We have slaughtered here at Jasenovac more people than the Ottoman Empire was able to do during its occupation of Europe."[56] Other Ustaše sources give other estimates: a circular of the Ustaše general headquarters that reads: "the concentration and labor camp in Jasenovac can receive an unlimited number of internees". In the same spirit, Miroslav Filipović-Majstorović, once captured by Yugoslav forces, admitted that during his three months of administration, 20,000 to 30,000 people had been killed.[111]

Since it became clear that his confession was an attempt to somewhat minimize the rate of crimes committed in Jasenovac, Filipović-Majstorović's figures are deemed to be far lower than the true numbers, which some sources have estimated at 30,000-40,000.[112]

Vjekoslav "Maks" Luburić, at a ceremony on 9 October 1942[113]

A report of the National Committee of Croatia for the investigation of the crimes of the occupation forces and their collaborators, dated 15 November 1945, which was commissioned by the new government of Yugoslavia under Josip Broz Tito, stated that 500,000-600,000 people were killed at the Jasenovac complex. These figures were cited by researchers Israel Gutman and Menachem Shelach in the Encyclopedia of the Holocaust (1990) and the Simon Wiesenthal Center.[114] Mosa Pijade and Edvard Kardelj used this number in the war reparations meetings. Thus the proponents of these numbers were subsequently accused of artificially inflating them for purpose of obtaining war reparations. All in all, the state-commission's report has been the only public and official document about the number of victims during the 45 years of second Yugoslavia.[115]

The state's total war casualties of 1,700,000 as presented by Yugoslavia at the Paris Peace Treaties, were produced by a math student, Vladeta Vučković, at the Federal Bureau of Statistics.[116] Vučković later admitted his estimates included demographic losses i.e., factoring in the estimated population increase), while actual losses would have been significantly lower.[116] Vučković's estimates were rejected by Germany during war reparations talks.

Forensic investigations

Between 22 and 27 June 1964, exhumations of bodies and the use of sampling methods was conducted at Jasenovac by Vida Brodar and Anton Pogačnik from Ljubljana University, and Serbian anthropologist Srboljub Živanović from the University of Novi Sad. During the Yugoslav wars, Živanović published what he claimed were the full results of the studies, which he claimed had been suppressed by Tito's government to put less emphasis on the crimes of the Ustaše. According to Živanović, the research gave strong support to the victim counts of more than 500,000, with estimates of 700,000-800,000 being realistic, stating that in every mass grave there are 800 skeletons.

Victim lists

- The Jasenovac Memorial Area maintains a list of the names of 80,914 Jasenovac victims, including 45,923 Serbs, 16,045 Romanies, 12,765 Jews, 4,197 Croats, 1,113 Bosnian Muslims and 871 people of other ethnic backgrounds. The memorial estimates total deaths at 85,000 to 100,000.[117]

- The Belgrade Museum of the Holocaust keeps a list of the names of 80,022 victims (mostly from Jasenovac), including approximately 52,000 Serbs, 16,000 Jews, 12,000 Croats and 10,000 Romanies.

- Antun Miletić, a researcher at the Military Archives in Belgrade, has collected data on Jasenovac since 1979. His list contains 77,200 named victims, of whom 41,936 are Serbs.[118]

- In 1998, the Bosniak Institute published SFR Yugoslavia's final List of War Victims from the Jasenovac Camp (created in 1992).[119] The list contained the names of 49,602 victims at Jasenovac, including 26,170 Serbs, 8,121 Jews, 5,900 Croats, 1471 Romanies, 787 Bosnian Muslims, 6,792 people of unidentifiable ethnicity, and some listed simply as "others".[119] Another list published by that institution, which names victims who died between April and November 1944, lists 4,892 names.

Estimates by Holocaust institutions

The Yad Vashem center claims that more than 500,000 Serbs were murdered in Croatia, 250,000 were expelled, and another 200,000 were forced to convert to Catholicism.[120] including those killed at Jasenovac.[121] The same figures are cited by the Simon Wiesenthal center.

in the Encyclopedia of the Holocaust which was published in 1990, Menachem Shelach and Israel Gutman state that the total number of victims is 600,000, and that 20,000-25,000 of them were Jews. However, they only mention Jasenovac as the site where the murders took place. Furthermore, they mention that most of the Croatian Jewish victims were deported to Auschwitz after August 1942.[122] On the other hand, however, as of 2012, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum estimates that the Ustaše regime murdered between 45,000 and 52,000 ethnic Serbs in Jasenovac between 1941 and 1945, and that during the period of Ustaše rule, a total of between 320,000 and 340,000 ethnic Serbs were killed in Croatia and Bosnia.[16]

Statistical estimates

In the 1980s, calculations were made by Serb statistician Bogoljub Kočović and Croat economist Vladimir Žerjavić, who claimed that total number of victims in Yugoslavia was less than 1,700,000 which was the official estimate at the time, both concluding that the number of victims was around one million. Žerjavić calculated furthermore, claiming that the number of victims in the Independent State of Croatia was between 300,000 and 350,000, including 80,000 victims in Jasenovac, as well as thousands of deaths in other camps and prisons.[123]

However, these estimates have been dismissed as biased and unreliable especially on the Serbian side. The mere 0.1% change of the (unknown) birth rate would contribute more to the number of victims than Žerjavić's claim of the number of Serbs killed in Jasenovac (50,000) and his calculation has a deficiency rate of 30%. Žerjavić has been dismissed as a nationalist even by Kočović, and his estimates of the number of fatalities in the Bosnian War of the 1990s (300,000 killed) was three times greater than ICTY data and Bosnian official estimates after the war (100,000 killed), and sheds light on problems with his credibility. He was accused by some Croatian historians of being a plagiarist and the "court statistician".[124]

Serbian experts criticized these estimates as far too low, since the demographic calculations assumed arbitrarily that the growth rate for Serbs in Bosnia (which was absorbed by the Independent State of Croatia during the Second World War) was equal to the total growth rate throughout the former Yugoslavia (1.1% at the time). According to Serbian sources, however, the actual growth rate in this region was 2.4% (1921–31) and 3.5% (1949–53). This method is considered very unreliable by critics because there is no reliable data on total births during this period, yet the results depend strongly on the birth rate - just a change of 0.1% in birth rate changes the victim count by 50,000. According to the census, the number of Serbs between last prewar (1931) and first post war (1948) census has gone up from 1,028,139 to around 1,200,000. The Yugoslav Federal Bureau of Statistics in 1964 created a list of World War II victims with 597,323 names and deficiency estimated at 20-30% which is giving between 750,000 and 780,000 victims. Together with estimated 200,000 killed collaborators and quislings, the total number would reach about one million. This Yugoslav Federal Bureau of Statistics list was declared a state secret in 1964 and only published in 1989.[106]

Aftermath

After World War II, most of the remaining Ustaša went underground or fled to countries such as Australia, Canada, the United States and Germany, with the assistance of Roman Catholic clerics and grassroots supporters. Yugoslav President Marshal Josip Broz Tito never visited the sites where massacres of Serbs took place, particularly Jasenovac, as he sought to make the people of Yugoslavia forget the Ustaše's crimes in the name of "brotherhood and unity".[125]

Israeli President Moshe Katsav visited Jasenovac in 2003. His successor, Shimon Peres, paid homage to the camp's victims when visited Jasenovac on 25 July 2010 and laid a wreath at the memorial. Peres dubbed the Ustaše's crimes to be a "demonstration of sheer sadism".[126][127]

On 17 April 2011, in a commemoration ceremony, Croatian President Ivo Josipović warned that there were "attempts to drastically reduce or decrease the number of Jasenovac victims", adding, "faced with the devastating truth here that certain members of the Croatian people were capable of committing the cruelest of crimes, I want to say that all of us are responsible for the things that we do." At the same ceremony, then Croatian Prime Minister Jadranka Kosor said, "there is no excuse for the crimes and therefore the Croatian government decisively rejects and condemns every attempt at historical revisionism and rehabilitation of the fascist ideology, every form of totalitarianism, extremism and radicalism... Pavelić's regime was a regime of evil, hatred and intolerance, in which people were abused and killed because of their race, religion, nationality, their political beliefs and because they were the others and were different."[128]

Notable war-criminals

- Ante Pavelić, leader of Croatia during the Second World War, shot by Blagoje Jovović, a Montenegrin Serb working for the Yugoslavian secret service, near Buenos Aires, Argentina on 9 April 1957. Pavelić later died of his injuries in a hospital in Madrid, Spain.

- Dido Kvaternik, considered the second most important person in Croatia after Ante Pavelić, died in a car accident along with his two daughters, in Argentina in 1962.

- Miroslav Filipović–Majstorović (born Tomislav Filipović), a Franciscan friar, reportedly expelled from the order, was infamous for his commands of Jasenovac and Stara-Gradiška,[129] where he was known as Fra Satana (Father Satan) because of his cruelty. He was captured by the Yugoslav communist forces, tried and executed in 1946, wearing his clerical garb.

- Maks Luburić was the commander of the Ustaška Odbrana, or Ustaše Defense, and he was thus held responsible for all crimes committed under his supervision at Jasenovac, which he visited approximately two to three times per month.[130] He fled to Spain, where he was assassinated in 1969 by Ilija Stanić on 20 April 1969 in Carcaixent.[131]

- Mile Budak, a Croatian politician, was executed for war crimes and crimes against humanity on 7 June 1945.

- Dinko Šakić fled to Argentina, but was eventually extradited, tried and sentenced, in 1999, by Croatian authorities to 20 years in prison, dying in prison in 2008. His wife, Nada, an Ustaše camp guard, was the sister or half-sister of Maks Luburić. She escaped punishment when Argentina refused to extradite her to Croatia.

- Petar Brzica was an Ustaša officer who, on the night of 29 August 1942, allegedly slaughtered over 1,360 people. Brzica's fellow Ustašes participated in that crime, as part of a throat cutting competition.[132] Brzica's post-war fate is unknown.

See also

- Anti-Serb sentiment

- Anti-Orthodoxy

- Catholic clergy involvement with the Ustaše

- Glina, Croatia

- Kragujevac massacre

- Hungarian occupation of Yugoslav territories

- Banat (1941–44)

- The Holocaust

- Garavice

References

- ↑ Žerjavić, Vladimir (1993). Yugoslavia - Manipulations with the number of Second World War victims. Croatian Information Centre. ISBN 0-919817-32-7.

- ↑ "Žrtve licitiranja - Sahrana jednog mita, Bogoljub Kočović". NIN (in Serbian). 12 January 2006. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- 1 2 "Jasenovac". Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ↑ Binder, David (16 May 1991). "The Serbs and Croats: So Much in Common, Including Hate". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ↑ Nenad Antonijević (15 March 2005). "Albanski zločini nad Srbima na Kosovu i Metohiji u Drugom svetskom ratu - Nacistički genocid nad Srbima". Pravoslavlje #912. Politika A.D. ISSN 0555-0114. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ↑ Pavle Dželetović Ivanov (7 September 2003). "Zapisi o arbanaškim zločinima nad Srbima (11) - Džamija na zgarištu". Glas javnosti (in Serbian).

- 1 2 3 Pavlowitch 2008, p. 34.

- ↑ "Serbian Genocide". hcombatgenocide.org. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ↑ MacDonald, David Bruce (2002). Balkan Holocausts?: Serbian and Croatian Victim Centered Propaganda and the War in Yugoslavia (1.udg. ed.). Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 261. ISBN 978-0-7190-6467-8.

- ↑ Mylonas, Christos (2003). Serbian Orthodox Fundamentals: The Quest for an Eternal Identity. Budapest: Central European University Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-963-9241-61-9.

- ↑ Jonsson, David J. (2006). Islamic economics and the final jihad: the Muslim brotherhood to Leftist/Marxist-Islamist alliance. Xulon Press. p. 504. ISBN 978-1-59781-980-0.

- ↑ Crowe, David (2011). Crimes of State Past and Present: Government-Sponsored Atrocities and International Legal Responser. Routledge. pp. 45–46.

- ↑ McCormick 2014.

- ↑ Bulajić, Milan (1989). Ustaški zločini genocida i suđenje Andriji Artukoviću (1986). Rad.

- ↑ "Croatia" (PDF). Shoah Resource Center - Yad Vashem.

- 1 2 3 "Jasenovac". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. 2007. Retrieved 26 September 2007.

- ↑ C. Michael McAdams (16 August 1992). "CROATIA: MYTH AND REALITY" (PDF). Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ↑ Hory & Broszat 1964, pp. 13–38.

- ↑ Viktor Meier. Yugoslavia: a history of its demise English edition. London, UK: Routledge, 1999, p. 125.

- ↑ Tomasevich (2001), pp. 351–52

- 1 2 3 4 Fischer 2007, p. 207.

- ↑ Fischer 2007, pp. 207–208.

- 1 2 Butić-Jelić, Fikreta. Ustaše i Nezavisna Država Hrvatska 1941–1945. Liber, 1977.

- ↑ Djilas, p. 114.

- ↑ Fischer 2007, p. ?.

- ↑ Tomasevich (2001), p. 466

- ↑ "Deciphering the Balkan Enigma: Using History to Inform Policy" (PDF). Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ Lo State-commission, pp. 30, 40-41

- ↑ Secanja jevreja na logor Jasenovac, pp. 40–41, 98, 131, 171

- ↑ See: Encyclopedia of the holocaust, "Jasenovac"

- ↑ State-commission, pp. 9–11, 46-47

- ↑ "Land/Forstwirtschaft: Garbenmesser". Hr-online.de. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- ↑ Nikolić, Dr Nikola (author) & Jože Zupančić (translator), Taborišče smrti – Jasenovac, Založba "Borec", Ljubljana 1969.

The knife described on page 72: 'Na koncu noža, tik bakrene ploščice, je bilo z vdolbnimi črkami napisano "Grafrath gebr. Solingen", na usnju pa reliefno vtisnjena nemška tvrtka "Graeviso"'

Picture of the knife with description on page 73: 'Posebej izdelan nož, ki so ga ustaši uporabljali pri množičnih klanjih. Pravili so mu "kotač" - kolo - in ga je izdelovala nemška tvrtka "Graeviso"' - ↑ State-commission, pp. 13, 25, 27, 56-60

- ↑ "Donja Gradina Memorial Site". Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- ↑ State-commission, pp. 38–39

- ↑ Lituchy 2006, p. 117.

- ↑ The Holocaust Research Project

- ↑ "Timebase Multimedia Chronography (TM) - Timebase 1945". Humanitas-international.org. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ↑ The Destruction of the European Jews by Raul Hilberg, Yale University Press, 2003; ISBN 0-300-09557-0, 9780300095579, page 760

- ↑ Koncentracioni logor Jasenovac 1941–1945: dokumenta By Antun Miletić, Goran Miletić, Dušan M. Obradović, Mile Simić &, Natalija Matić. Narodna knjiga, Beograd, 1986, pp. 766, 921

- ↑ "Zlocini Okupatora Nijhovih Pomagaca Harvatskoj Protiv Jevrija", pp. 144–45

- ↑ Shelach, p. 196, and in "Zločini fašističkih okupatora i njihovih pomagača protiv Jevreja u Jugoslaviji", by Zdenko Levental, Savez jevrejskih opština Jugoslavije, Beograd 1952, pp. 144–45

- ↑ Persen, Mirko . "Ustaski Logori", p. 105

- ↑ Secanja jevreja na logor Jasenovac, pp. 40–41, 58, 76, 151

- ↑ Shelach, pp. 196–97

- ↑ Menachem Shelach (ed.), History of the Holocaust: Yugoslavia, p. 162

- ↑ Avro Manhattan, The Vatican's Holocaust

- ↑ War of Words: Washington Tackles the Yugoslav Conflict by Danielle S. Sremac, Praeger (30 October 1999), pp. 38-39; ISBN 0-275-96609-7/ISBN 978-0-275-96609-6

- ↑ "Concentration Camp Listing". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ↑ Ramet 2006, p. 116.

- ↑ "Numbers of victims at Jadovno victims association". Jadovno.com. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ↑ Pyle, Christopher H.; Extradition, politics, and human rights; Temple University Press, 2001; ISBN 1-56639-823-1; p. 132.

- ↑ Lukajić, . "Fratri i Ustase Kolju".

[interview with Borislav Seva] "they threw Rade Zrnic into the brick factory fires alive!"

- ↑ State-commission, pp. 14, 27, 31, 42-43, 70

- 1 2 Paris 1961, p. 132.

- 1 2 3 Ramet 2006, p. 119.

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, p. 536.

- ↑ Misha Glenny; Tom Nairn (1999). The Balkans, 1804-1999: nationalism, war and the great powers. Granta. p. 500. ISBN 978-1-86207-050-9.

- ↑ Paris 1961, p. 104.

- ↑ Paris 1961, p. 82.

- ↑ Paris 1961, p. 60.

- ↑ Ramet 2006, p. 120.

- ↑ Paris 1961, p. 59.

- ↑ Copley, Gregory. Defense & Foreign Affairs Strategic Policy. Volume XX, Number 12, 31 December 1992 (in English)

- ↑ Ramet 2006, p. 118.

- 1 2 Cohen 1996, p. 90.

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, p. 546.

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, p. 394.

- ↑ Ramet 2006, p. 312.

- ↑ Enver Redžić (2005). Bosnia and Herzegovina in the Second World War. Psychology Press. pp. 71–. ISBN 978-0-7146-5625-0.

- ↑ Alex J. Bellamy (2003). The Formation of Croatian National Identity: A Centuries-old Dream. Manchester University Press. pp. 138–. ISBN 978-0-7190-6502-6.

- ↑ Crowe, David M. (13 September 2013). Crimes of State Past and Present: Government-Sponsored Atrocities and International Legal Responses. Routledge. pp. 61–. ISBN 978-1-317-98682-9.

- ↑ Fischer 2007, p. 228.

- ↑ Pavlowitch 2008, p. 62.

- ↑ Pomeranz, Frank. Fall of the Cetniks, History of the Second World War, vol 4, p. 1509

- ↑ Singleton, Frederick Bernard (1985). A Short History of the Yugoslav Peoples. Cambridge University Press. p. 194. ISBN 0-521-27485-0.

- ↑ Roberts (1973), p. 328

- ↑ Zvonimir Golubović (1991). Racija u južnoj Bačkoj 1942. godine. Istorijski muzej Vojvodine. pp. 146–47.

- ↑ Enciklopedija Novog Sada, Sveska 5. Novi Sad. 1996. p. 196.

- ↑ Dimitrije Boarov (2001). Politička istorija Vojvodine: u trideset tri priloga. CUP. p. 183.

- ↑ Zolo, Danilo. Invoking humanity: war, law, and global order. London, UK/New York, NY: Continuum International Publishing Group (2002), p. 24.

- ↑ Mojzes (2011), p. 95

- ↑ Bogdanović, Dimitrije: "The Book on Kosovo", 1990. Belgrade: Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, 1985, p. 2428.

- ↑ Genfer, Der Kosovo-Konflikt, Munich: Wieser, 2000, p. 158.

- ↑ Vickers 1999, p. 152.

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, p. 152.

- ↑ Fischer 1999, p. 215.

- ↑ Nafziger 1992, p. 21.

- ↑ Judah 2002, p. 28.

- ↑ Cohen 1996, p. 100.

- ↑ Mojzes 2011, pp. 94–95.

- ↑ Yeomans 2006, p. 31.

- ↑ Williamson, G. The SS: Hitler's Instrument of Terror

- ↑ History of the United Nations War Crimes Commission and the Development of the Laws of War (p. 528), United Nations War Crimes Commission, London: HMSO, 1948.

- ↑ Drago Hedl (10 November 2005). "Croatia's Willingness To Tolerate Fascist Legacy Worries Many". BCR Issue 73. IWPR. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- ↑ Schemo, Diana Jean (22 April 1993). "Anger Greets Croatian's Invitation To Holocaust Museum Dedication". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ↑ "Croatia probes why Hitler image was on sugar packets". Reuters. 20 February 2007. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ↑ "Wiesenthal Center Expresses Outrage At Massive Outburst of Nostalgia for Croatian fascism at Zagreb Rock Concert; Urges President Mesić to Take Immediate Action", wiesenthal.com; accessed 4 March 2014.

- ↑ (in Croatian) Vijesti.net: "stari govor Stipe Mesića: Pobijedili smo 10. travnja!", index.hr; accessed 4 March 2014.

- ↑ Lefkovits, Etgar (16 April 2008). "Melbourne eatery hails leader of Nazi-allied Croatia, Jerusalem Post, 16 April 2008". Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ↑ Paris 1961, p. 100.

- ↑ Paris 1961, p. 160.

- ↑ "Mass grave of history: Vatican's WWII identity crisis". JPost. 23 February 2010. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ↑ "History of the holocaust: Yugoslavia"

- 1 2 Federal Bureau of Statistics in 1964, Danas, 21 November 1989.

- ↑ "Croatian holocaust still stirs controversy". BBC News. 29 November 2001. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- ↑ "Balkan 'Auschwitz' haunts Croatia". BBC News. 25 April 2005. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

No one really knows how many died here. Serbs talk of 700,000. Most estimates put the figure nearer 100,000.

- ↑ Le Operazioni della unita Italiane in Jugoslavia. Rome (1978), pp. 141-48

- ↑ C. Falconi, The Silence of Pius XII, London (1970), p. 3308

- ↑ State-commission, p. 62

- ↑ Avro Manhattan, The Vatican's Holocaust.

- ↑ Paris 1961, p. 67.

- ↑ Shelach, p. 189

- ↑ Tomasevich (2001), p. 718

- 1 2 Danijela Nadj. "Vladimir Zerjavic - How the number of 1.7 million casualties of the Second World War has been derived". Hic.hr. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ↑ "Southeast Times: Exhibition aims to show truth about Jasenovac". Setimes.com. 27 November 2006. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ↑ Anzulovic, Branimir. Heavenly Serbia: From Myth to Genocide, C. Hurst & Company. London (1999).

- 1 2 Bošnjački Institut. Jasenovac: Žrtve rata prema podacima statističkog zavoda Jugoslavije. Bošnjački Institut Sarajevo, Sarajevo 1998.

- ↑ Yad Vashem website; accessed 28 May 2014.

- ↑ "Jasenovac" (PDF). Yad Vashem. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ↑ Shelach, Menachem; Gutman, Israel (1990). Encyclopedia of the Holocaust vol.1. pp. 739–740.

- ↑ Žerjavić actually first calculated 53,000, later brought up to 70,000 and eventually to 80,000. The details of his calculations remain disputed.

- ↑ Žerjavić accused of plagiarism, hic.hr; accessed 12 July 2015.

- ↑ "President Mesić in Vojnić". Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ↑ "Israel's Shimon Peres visits 'Croatian Auschwitz'". EJ Press. 25 July 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ↑ "Israel's Peres visits Croatian Auschwitsz". France24. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ↑ "Croatian Auschwitz must not be forgotten". B92. 17 April 2011. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ↑ State-commission for the investigation of the crimes of the occupation forces and their collaborators, pp. 31–32

- ↑ State-commission, pp. 28–29

- ↑ Guldescu, Stanko & John Prcela: Operation Slaughterhouse, p. 71. Dorrance, 1970.

- ↑ State-commission, pp. 50, 72

Sources

- Books

- Antonijević, Nenad (2009). Mirković, Jovan, ed. Албански злочини над Србима на Косову и Метохији у Другом светском рату, документа, друго измењено и допуњено издање (PDF). Belgrade: Музеј жртава геноцида.

- Bulajić, Milan (1992). Tudjman's "Jasenovac Myth": Ustasha Crimes of Genocide. Belgrade: The Ministry of information of the Republic of Serbia.

- Bulajić, Milan (1994). Tudjman's "Jasenovac Myth": Genocide against Serbs, Jews and Gypsies. Belgrade: Stručna knjiga.

- Bulajić, Milan (1994). The Role of the Vatican in the break-up of the Yugoslav State: The Mission of the Vatican in the Independent State of Croatia. Ustashi Crimes of Genocide. Belgrade: Stručna knjiga.

- Bulajić, Milan (2002). Jasenovac: The Jewish-Serbian Holocaust (the role of the Vatican) in Nazi-Ustasha Croatia (1941-1945). Belgrade: Fund for Genocide Research, Stručna knjiga.

- Cohen, Philip J. (1996). Serbia's Secret War: Propaganda and the Deceit of History. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 0-89096-760-1.

- Dakina, Gojo Riste (1994). Genocide Over the Serbs in the Independent State of Croatia: Be Catholic Or Die. Institute of Contemporary History.

- Dedijer, Vladimir (1992). The Yugoslav Auschwitz and the Vatican: The Croatian Massacre of the Serbs During World War II. Amherst: Prometheus Books.

- Djilas, Aleksa (1991). The Contested Country: Yugoslav Unity and Communist Revolution, 1919-1953. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-16698-1.

- Ђурић, Вељко Ђ. (1991). Прекрштавање Срба у Независној Држави Хрватској: Прилози за историју верског геноцида. Београд: Алфа.

- Fischer, Bernd J. (2007). Balkan Strongmen: Dictators and Authoritarian Rulers of South-Eastern Europe. Purdue University Press. ISBN 1-55753-455-1.

- Hory, Ladislaus; Broszat, Martin (1964). Der kroatische Ustascha-Staat1941-1945. Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt.

- Kolstø, Pål (2011). "The Serbian-Croatian Controversy over Jasenovac". Serbia and the Serbs in World War Two. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 225–246.

- Korb, Alexander (2010). "A Multipronged Attack: Ustaša Persecution of Serbs, Jews, and Roma in Wartime Croatia". Eradicating Differences: The Treatment of Minorities in Nazi-Dominated Europe. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 145–163.

- Levy, Michele Frucht (2011). "'The Last Bullet for the Last Serb': The Ustaša Genocide against Serbs: 1941–1945". Crimes of State Past and Present: Government-Sponsored Atrocities and International Legal Responses. Routledge. pp. 54–84.

- Lituchy, Barry M., ed. (2006). Jasenovac and the Holocaust in Yugoslavia: Analyses and Survivor Testimonies. New York: Jasenovac Research Institute.

- McCormick, Robert B. (2014). Croatia Under Ante Pavelić: America, the Ustaše and Croatian Genocide. London-New York: I.B. Tauris.

- Mirković, Jovan (2014). Злочини над Србима у Независној Држави Хрватској - фотомонографија [Crimes against Serbs in the Independent State of Croatia - photomonograph]. Belgrade: Svet knjige. ISBN 978-86-7396-465-2.

- Mojzes, Paul (2008). "The Genocidal Twentieth Century in the Balkans". Confronting Genocide: Judaism, Christianity, Islam. Lanham: Lexington Books. pp. 151–182.

- Mojzes, Paul (2011). Balkan Genocides: Holocaust and Ethnic Cleansing in the 20th Century. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Paris, Edmond (1961). Genocide in Satellite Croatia, 1941-1945: A Record of Racial and Religious Persecutions and Massacres. Chicago: American Institute for Balkan Affairs.

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2008). Hitler's New Disorder: The Second World War in Yugoslavia. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building and Legitimation, 1918–2005. New York: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-34656-8.

- Rivelli, Marco Aurelio (1998). Le génocide occulté: État Indépendant de Croatie 1941–1945 [Hidden Genocide: The Independent State of Croatia 1941–1945] (in French). Lausanne: L'age d'Homme.

- Rivelli, Marco Aurelio (1999). L'arcivescovo del genocidio: Monsignor Stepinac, il Vaticano e la dittatura ustascia in Croazia, 1941-1945 [The Archbishop of Genocide: Monsignor Stepinac, the Vatican and the Ustaše dictatorship in Croatia, 1941-1945] (in Italian). Milano: Kaos.

- Rivelli, Marco Aurelio (2002). "Dio è con noi!": La Chiesa di Pio XII complice del nazifascismo ["God is with us!": The Church of Pius XII accomplice to Nazi Fascism] (in Italian). Milano: Kaos.

- Roberts, Walter R. (1973). Tito, Mihailović and the Allies 1941–1945. Rutgers University Press.

- Симић, Сима (1958). Прекрштавање Срба за време Другог светског рата. Титоград: Графички завод.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (2001). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945: Occupation and Collaboration. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Yeomans, Rory (2013). Visions of Annihilation: The Ustasha Regime and the Cultural Politics of Fascism, 1941-1945. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Journals

- Antonijević, Nenad (2003). "Stradanje srpskog i crnogorskog civilnog stanovništva na Kosovu i Metohiji 1941. godine". Dijalog povjesničara-istoričara. Zadar: Friedrich Nauman Stiftung. 8: 355–369.

- Antonijević, Nenad M. (2016). "Ратни злочини на Косову и Метохији: 1941-1945. године.". Универзитет у Београду, Филозофски факултет.

- Bartulin, Nevenko (October 2007). "Ideologija nacije i rase: ustaški režim i politika prema Srbima u Nezavisnoj Državi Hrvatskoj 1941-1945." (PDF). Radovi (in Croatian). Institute of Croatian History. 39 (1): 209–241. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- Bartulin, Nevenko (2008). "The Ideology of Nation and Race: The Croatian Ustasha Regime and its Policies toward the Serbs in the Independent State of Croatia 1941-1945". Croatian Studies Review. 5: 75–102.

- Biondich, Mark (2005). "Religion and Nation in Wartime Croatia: Reflections on the Ustaša Policy of Forced Religious Conversions, 1941-1942". The Slavonic and East European Review. 83 (1): 71–116.

- Byford, Jovan (2007). "When I say “The Holocaust,” I mean “Jasenovac”: Remembrance of the Holocaust in contemporary Serbia". East European Jewish Affairs. 37 (1): 51–74. doi:10.1080/13501670701197946.

- Cvetković, Dragan (2011). "Holokaust u Nezavisnoj Državi Hrvatskoj - numeričko određenje" (PDF). Istorija 20. veka: Časopis Instituta za savremenu istoriju. 29 (1): 163–182.

- Hehn, Paul N. (1971). "Serbia, Croatia and Germany 1941–1945: Civil War and Revolution in the Balkans". Canadian Slavonic Papers. University of Alberta. 13 (4): 344–373.

- Kataria, Shyamal (2015). "Serbian Ustashe Memory and Its Role in the Yugoslav Wars, 1991–1995". Mediterranean Quarterly. 26 (2): 115–127. doi:10.1215/10474552-2914550.

- Levy, Michele Frucht (2009). "“The Last Bullet for the Last Serb”: The Ustaša Genocide against Serbs: 1941–1945". Nationalities Papers. 37 (6): 807–837. doi:10.1080/00905990903239174.

- Yeomans, Rory (2005). "Cults of Death and Fantasies of Annihilation: The Croatian Ustasha Movement in Power, 1941–45". Central Europe. 3 (2): 121–142.

- Yeomans, Rory (2015). "The Racial Idea in the Independent State of Croatia: Origins and Theory". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 29 (3): 504–506.

- Encyclopaedia

- Gutman, Israel, ed. (1990). "Ustase". Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. 4. Macmillan.

- Articles

- Latinović, Goran (2006). "On Croatian history textbooks". Association of Descendants and Supporters of Victims of Complex of Death Camps NDH, Gospić-Jadovno-Pag 1941.

External links

- "Genocide in Croatia 1941–1945" (PDF). Serbian National Defense Council of Canada; Serbian National Defense Council of America. 1976. OCLC 26383552.