Genetic studies on Turkish people

In population genetics, research has been made to study the genetic origins of the modern Turkish people in Turkey. These studies sought to determine whether the modern Turks have a stronger genetical affinity with the Turkic peoples of Central Asia from where the Seljuk Turks began migrating to Anatolia following the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, which led to the establishment of the Anatolian Seljuk Sultanate in the late 11th century; or if they instead largely descended from the indigenous peoples of Anatolia who were culturally assimilated during the Seljuk and Ottoman periods, with assimilation policies such as the devshirme system and the jizya tax.

Autosomal studies with recent methodology estimate the Central Asian contribution in Turkish people at 13-15%[1][2][3] noting that results may indicate previous population movements (e.g. migration, admixture) or genetic drift, given the fact that Europe and South Asia have some genetic relatedness.

An autosomal study on Turkish genetics (on 16 individuals) predicted that the weight of Central Asian migration legacy of the Turkish people is estimated at 21.7%.[4] The authors conclude on the basis of previous studies that "South Asian contribution to Turkey's population was significantly higher than East/Central Asian contributions, suggesting that the genetic variation of medieval Central Asian populations may be more closely related to South Asian populations, or that there was continued low level migration from South Asia into Anatolia." They note that these weights are not direct estimates of the migration rates as the original donor populations are not known, and the exact kinship between current East Asians and the medieval Oghuz Turks is uncertain. For instance, genetic pools of Central Asian Turkic peoples is particularly diverse and modern Oghuz Turkmens living in Central Asia are with slightly higher West Eurasian genetic component than East Eurasian.[5][6]

Several studies have concluded that the genetic haplogroups indigenous to Western Asia have the largest share in the gene pool of the present-day Turkish population.[2][2][7][8][9][10][11][12][13] An admixture analysis determined that the Anatolian Turks share most of their genetic ancestry with non-Turkic populations in the region and the 12th century is set as an admixture date.[14] However, isolates with dominant Central Asian genetic makeup were found in an Afshar village near Ankara.

Central Asian and Uralic connection

The question to what extent a gene flow from Central Asia to Anatolia has contributed to the current gene pool of the Turkish people, and what the role is in this of the 11th century settlement by Oghuz Turks, has been the subject of several studies. A factor that makes it difficult to give reliable estimates, is the problem of distinguishing between the effects of different migratory episodes. Thus, although the Turks settled in Anatolia (peacefully or after war events) with cultural significance, including the introduction of the Turkish language and Islam, the genetic significance from Central Asia might have been slight.[8][16]

Some of the Turkic peoples originated from Central Asia and therefore are possibly related with Xiongnu.[17] A majority (89%) of the Xiongnu sequences can be classified as belonging to Asian haplogroups and nearly 11% belong to European haplogroups.[17] This findings indicate that the contacts between European and Asian populations were anterior to the Xiongnu culture,[17] and it confirms results reported for two samples from an early 3rd century B.C. Scytho-Siberian population.[18]

According to another archeological and genetic study in 2010, the DNA found in three skeletons in 2000-year-old elite Xiongnu cemetery in Northeast Asia belonged to C3, D4 and including R1a. The evidence of paternal R1a support the Kurgan expansion hypothesis for the Indo-European expansion from the Volga steppe region.[19] As the R1a was found in Xiongnu people[19] and the present-day people of Central Asia[20] Analysis of skeletal remains from sites attributed to the Xiongnu provides an identification of dolichocephalic Mongoloid, ethnically distinct from neighboring populations in present-day Mongolia.[21]

According to a different genetic research on 75 individuals from various parts of Turkey, Mergen et al. revealed that the "genetic structure of the mtDNAs in the Turkish population bears similarities to Turkic Central Asian populations".[15]

Overall, modern Turks are most related to neighbouring West Asian populations. A study looking into allele frequencies suggested that there was a lack of genetic relationship between contemporary Mongols and Turks, despite their linguistic and cultural relationship.[22] In addition, another study looking into HLA genes allele distributions indicated that Anatolians did not significantly differ from other Mediterranean populations.[16] Multiple studies suggested an elite dominance-driven linguistic replacement model to explain the adoption of Turkish language by Anatolian indigenous inhabitants.[11][12]

Haplogroup distributions in Turkish people

.png)

According to Cinnioğlu et al. (2004),[7] there are many Y-DNA haplogroups present in Turkey. The majority of the haplogroups found in the people of Turkey are shared with their West Asian and Caucasian neighbours. The most commonly found haplogroup in Turkey is J2 (24%), which is widespread among the Mediterranean, Caucasian and West Asian populations. By contrast, Central Asian haplogroups are rarer (N and Q – 5.7%) but this figure may rise to 36% if K, R1a, R1b and L (which infrequently occur in Central Asia, but are notable in many other Western Turkic groups) are also included. Haplogroups that are common in Europe (R1b and I – 20%), South Asia (L, R2, H – 5.7%) and Africa (A, E3*, E3a – 1%) are also present.

Some of the percentages identified were:[7]

- J2=24% - J2 (M172)[7] Typical of Mediterranean, Caucasian, Western and Central Asian populations.[23]

- R1b=15.9%[7] Widespread in western Eurasia, with distinct "west Asian" and "west European" lineages.

- G=10.9%[7] – Typical of people from the Caucasus and to a lesser extent the Middle East.

- E3b-M35=10.7%[7] (E3b1-M78 and E3b3-M123 accounting for all E representatives in the sample, besides a single E3b2-M81 chromosome). E-M78 occurs commonly, and is found in northern and eastern Africa, and in western Asia.[24] Haplogroup E-M123 is found in both Africa and Eurasia.

- J1=9%[7] – Typical amongst people from the Arabian peninsula and Dagestan (ranging from 3% from Turks around Konya to 12% in Kurds).

- R1a=6.9%[7] – Common in various Central Asian, Indian, Central- and Eastern European populations.

- I=5.3%[7] – Common in Balkans and eastern Europe, possibly representing a back-migration to Anatolia.

- K=4.5%[7] – Typical of Asian populations and Caucasian populations.

- L=4.2%[7] – Typical of the Indian subcontinent and Khorasan populations. Found sporadically in the Middle East and the Caucasus.

- N=3.8%[7] – Typical of Uralic, Siberian and Altaic populations.

- T=2.5%[7] – Typical of Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, Northeast African and South Asian populations

- Q=1.9%[7] – Typical of Northern Altaic populations

- C=1.3%[7] – Typical of Mongolic and Siberian populations

- R2=0.96% [7] – Typical of South Asian population

Others markers than occurs in less than 1% are H, A, E3a , O , R1*.

Further research on Turkish Y-DNA groups

A study in Turkey by Gökçümen (2008)[25] took into account oral histories and historical records. They went to four settlements in Central Anatolia and didn't do a random selection from a group of university students like in many other studies. Accordingly, here are the results:

1) In an Afshar village near Ankara where, according to oral tradition, the ancestors of the inhabitants came from Central Asia, the researchers found that 57% of the villagers had haplogroup L, 13% had haplogroup Q, and 3% had haplogroup N; thus indicating that the L haplogroups in Turkey are of Central Asian heritage rather than South Asian, although these Central Asians probably received the L markers from the South Asians at the beginning. These Asian groups add up to 73% in this village. Furthermore, 10% of these Afshars had haplogroups E3a and E3b, while only 13% had haplogroup J2a, the most common in Turkey.

2) The inhabitants of an older Turkish village which didn't receive much migration had about 25% of haplogroup N and 25% of J2a, with 3% of G and close to 30% of R1 variants (mostly R1b).

Whole genome sequencing

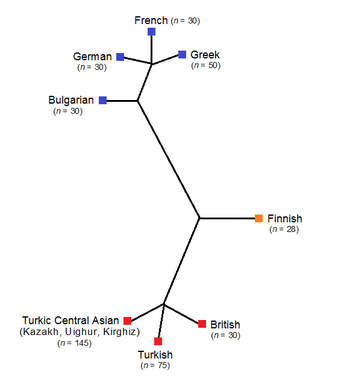

A study regarding Turkish genetics in 2014 has utilized the whole genome sequencing of Turkish individuals.[4] Led by Can Alkan at the University of Washington in Seattle, the study has been published in the journal BMC Genomics. The authors of the study show that the genetic variation of the contemporary Turkish population clusters with South European populations, as expected, but also shows signatures of relatively recent contribution from ancestral East Asian populations. They estimate the weights for the migration events predicted to originate from the East Asian branch into current-day Turkey was at 21.7% (see Figure 2 by Alkan et al.).[4]

"(B) A population tree based on “Treemix” analysis. The populations included are as follows: Turkey (TUR); Tuscans in Italy (TSI); Iberian populations in Spain (IBS); British from England and Scotland (GBR); Finnish from Finland (FIN); Utah residents with Northern and Western European ancestry (CEU); Han Chinese in Beijing, China (CHB); Japanese in Tokyo, Japan (JPT); Han Chinese South (CHS); Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria (YRI); Luhya in Webuye, Kenya (LWK). Populations with high degree of admixture (Native American and African American populations) were not included to simplify the analysis. The Yoruban population was used to root the tree. In total four migration events were estimated. The weights for the migration events predicted to originate from the East Asian branch into current-day Turkey was 0.217, from the ancestral Eurasian branch into the Turkey-Tuscan clade was 0.048, from the African branch into Iberia was 0.026, from the Japanese branch into Finland was 0.079."[4]

Whole genome dense genotyping

Another study published in PLOS Genetics journal in 2015 [26] addressed the genetic origin 22 Turkic-speaking populations, representing their current geographic range, by analyzing genome-wide high-density genotype data. This study showed that Turkic-speaking peoples sampled across the Middle East, Caucasus, East Europe, and Central Asia share varying proportions of Asian ancestry that originate in a single area, southern Siberia and Mongolia. Mongolic- and Turkic-speaking populations from this area bear an unusually high number of long chromosomal tracts that are identical by descent with Turkic peoples from across west Eurasia. This study also showed that genetic admixture signal in these populations indicates that admixture occurred during the 9th–17th centuries, in agreement with the historically recorded Turkic nomadic migrations and later Mongol expansion.

Other studies

In 2001, Benedetto et al. revealed that Central Asian genetic contribution to the current Anatolian mtDNA gene pool was estimated as roughly 30%, by comparing the populations of Mediterranean Europe, and Turkic-speaking people of Central Asia.[28] However some similar early studies have a high probability of errors and biased estimates, which concluded even up to over 60% Central Asian origin of Y-DNA microsatellites.[29] In 2003, Cinnioğlu et al. made a research of Y-DNA including the samples from eight regions of Turkey, without classifying the ethnicity of the people, which indicated that high resolution SNP analysis totally provides evidence of a detectable weak signal (<9%) of gene flow from Central Asia, but this was an underestimate summarizing only haplogroups C, Q, O and N.[7] It was later observed that the male contribution from Central Asia to Turkish population with reference to the Balkans was 13%, for all non-Turkic speaking populations the Central Asian contribution was higher than in Turkey.[29] According to the study "the contributions ranging between 13%–58% must be considered with a caution because they harbor uncertainties about the state of pre-nomadic invasion and further local movements." A 2001 study concluded that the Central Asian contribution to Anatolia for Y-DNA is 12%, mtDNA 22%, alu insertion (autosomal) 15%, autosomal 22%, with respect to Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Uyghur, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan.[30] By that method, for Y-DNA, Alu, mtDNA except Iraq (13%) and Armenia (6%) for females, the Central Asian contribution to the hybrids (Armenia, Georgia, Northern Caucasus, Syria, Iran, Iraq, Lebanon) were similar or even higher than to those of Turkey and Azerbaijan.

In 2011 Aram Yardumian and Theodore G. Schurr published their study "Who Are the Anatolian Turks? A Reappraisal of the Anthropological Genetic Evidence." They revealed the impossibility of long-term, and continuing genetic contacts between Anatolia and Siberia, and confirmed the presence of significant mitochondrial DNA and Y-chromosome divergence between these regions, with minimal admixture. The research confirms also the lack of mass migration and suggested that it was irregular punctuated migration events that engendered large-scale shifts in language and culture among Anatolia's diverse autochthonous inhabitants.[12]

According to a 2012 study on ethnic Turkish people, "Turkish population has a close genetic similarity to Middle Eastern and European populations and some degree of similarity to South Asian and Central Asian populations."[2] At K = 3 level, using individuals from the Middle East (Druze and Palestinian), Europe (French, Italian, Tuscan and Sardinian) to obtatin a more representative database for Central Asia (Uygur, Hazara and Kyrgyz), clustering results indicated that the contributions were 45%, 40% and 15% for the Middle Eastern, European and Central Asian populations, respectively. For K = 4 level, results for paternal ancestry were 38% European, 35% Middle Eastern, 18% South Asian and 9% Central Asian. K= 7 results of paternal ancestry were 77% European, 12% South Asian, 4% Middle Eastern, 6% Central Asian. However, Hodoglugil et al. caution that results may indicate previous population movements (e.g. migration, admixture) or genetic drift, given Europe and South Asia have some genetic relatedness.[2] The study indicated that the Turkish genetic structure is unique, and admixture of Turkish people reflects the population migration patterns.[2] Among all sampled groups, the Adygei population (Circassians) from the Caucasus was closest to the Turkish samples.[2]

Other studies revealed that the peoples of the Caucasus (Georgians, Circassians, Armenians) are the closest to the Turkish population among sampled European (French, Italian), Middle Eastern (Druze, Palestinian), and Central (Kyrgyz, Hazara, Uygur), South (Pakistani), and East Asian (Mongolian, Han) populations.[2][31]

See also

- Demographics of Turkey

- History of the Turkish people

- Archaeogenetics of the Near East

- Genetic history of Europe

- Turkification

References and notes

- ↑ Ceren Caner Berkman et al. 2007

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Hodoğlugil, Uğur; Mahley, Robert W. (2012). "Turkish Population Structure and Genetic Ancestry Reveal Relatedness among Eurasian Populations". Annals of Human Genetics. 76 (2): 128–41. PMC 4904778

. PMID 22332727. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2011.00701.x.

. PMID 22332727. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2011.00701.x. - ↑ Hodoğlugil, Uğur; Mahley, Robert W. (2012). "Turkish Population Structure and Genetic Ancestry Reveal Relatedness among Eurasian Populations". Annals of Human Genetics. 76 (2): 128–141. PMC 4904778

. PMID 22332727. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2011.00701.x.

. PMID 22332727. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2011.00701.x. - 1 2 3 4 5 Alkan et al. (2014), BMC Genomics 2014, 15:963, Whole genome sequencing of Turkish genomes reveals functional private alleles and impact of genetic interactions with Europe, Asia and Africa

- ↑ The mtDNA composition of Uzbekistan: a microcosm of Central Asian patterns doi:10.1007/s00414-009-0406-z

- ↑

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Cinnioglu, Cengiz; King, Roy; Kivisild, Toomas; Kalfoglu, Ersi; Atasoy, Sevil; Cavalleri, Gianpiero L.; Lillie, Anita S.; Roseman, Charles C.; Lin, Alice A.; Prince, Kristina; Oefner, Peter J.; Shen, Peidong; Semino, Ornella; Cavalli-Sforza, L. Luca; Underhill, Peter A. (2004). "Excavating Y-chromosome haplotype strata in Anatolia". Human Genetics. 114 (2): 127–48. PMID 14586639. doi:10.1007/s00439-003-1031-4.

- 1 2 Rosser, Z; Zerjal, T; Hurles, M; Adojaan, M; Alavantic, D; Amorim, A; Amos, W; Armenteros, M; Arroyo, E; Barbujani, G (2000). "Y-Chromosomal Diversity in Europe is Clinal and Influenced Primarily by Geography, Rather than by Language". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 67 (6): 1526–43. PMC 1287948

. PMID 11078479. doi:10.1086/316890.

. PMID 11078479. doi:10.1086/316890. - ↑ Nasidze, I; Sarkisian, T; Kerimov, A; Stoneking, M (2003). "Testing hypotheses of language replacement in the Caucasus: Evidence from the Y-chromosome". Human Genetics. 112 (3): 255–61. PMID 12596050. doi:10.1007/s00439-002-0874-4 (inactive 2017-01-16).

- ↑ Arnaiz-Villena, A.; Karin, M.; Bendikuze, N.; Gomez-Casado, E.; Moscoso, J.; Silvera, C.; Oguz, F.S.; Sarper Diler, A.; De Pacho, A.; Allende, L.; Guillen, J.; Martinez Laso, J. (2001). "HLA alleles and haplotypes in the Turkish population: Relatedness to Kurds, Armenians and other Mediterraneans". Tissue Antigens. 57 (4): 308–17. PMID 11380939. doi:10.1034/j.1399-0039.2001.057004308.x.

- 1 2 Wells, R. S.; Yuldasheva, N.; Ruzibakiev, R.; Underhill, P. A.; Evseeva, I.; Blue-Smith, J.; Jin, L.; Su, B.; Pitchappan, R.; Shanmugalakshmi, S.; Balakrishnan, K.; Read, M.; Pearson, N. M.; Zerjal, T.; Webster, M. T.; Zholoshvili, I.; Jamarjashvili, E.; Gambarov, S.; Nikbin, B.; Dostiev, A.; Aknazarov, O.; Zalloua, P.; Tsoy, I.; Kitaev, M.; Mirrakhimov, M.; Chariev, A.; Bodmer, W. F. (2001). "The Eurasian Heartland: A continental perspective on Y-chromosome diversity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (18): 10244–9. Bibcode:2001PNAS...9810244W. JSTOR 3056514. PMC 56946

. PMID 11526236. doi:10.1073/pnas.171305098.

. PMID 11526236. doi:10.1073/pnas.171305098. - 1 2 3 Schurr, Theodore G.; Yardumian, Aram (2011). "Who Are the Anatolian Turks?". Anthropology & Archeology of Eurasia. 50 (1): 6–42. doi:10.2753/AAE1061-1959500101.

- ↑ Comas, D.; Schmid, H.; Braeuer, S.; Flaiz, C.; Busquets, A.; Calafell, F.; Bertranpetit, J.; Scheil, H.-G.; Huckenbeck, W.; Efremovska, L.; Schmidt, H. (2004). "Alu insertion polymorphisms in the Balkans and the origins of the Aromuns". Annals of Human Genetics. 68 (2): 120–7. PMID 15008791. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2003.00080.x.

- ↑ Yunusbayev, Bayazit; Metspalu, Mait; Metspalu, Ene; Valeev, Albert; Litvinov, Sergei; Valiev, Ruslan; Akhmetova, Vita; Balanovska, Elena; Balanovsky, Oleg; Turdikulova, Shahlo (2015). "The Genetic Legacy of the Expansion of Turkic-Speaking Nomads across Eurasia". PLoS Genetics. 11 (4): e1005068. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005068.

- 1 2 Mergen, Hatice; Öner, Reyhan; Öner, Cihan (2004). "Mitochondrial DNA sequence variation in the Anatolian Peninsula (Turkey)" (PDF). Journal of Genetics. 83 (1): 39–47. PMID 15240908. doi:10.1007/bf02715828.

- 1 2 Arnaiz-Villena, A.; Gomez-Casado, E.; Martinez-Laso, J. (2002). "Population genetic relationships between Mediterranean populations determined by HLA allele distribution and a historic perspective". Tissue Antigens. 60 (2): 111–21. PMID 12392505. doi:10.1034/j.1399-0039.2002.600201.x.

- 1 2 3 Keyser-Tracqui, Christine; Crubézy, Eric; Ludes, Bertrand (2003). "Nuclear and Mitochondrial DNA Analysis of a 2,000-Year-Old Necropolis in the Egyin Gol Valley of Mongolia". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 73 (2): 247–60. PMC 1180365

. PMID 12858290. doi:10.1086/377005.

. PMID 12858290. doi:10.1086/377005. - ↑ Clisson, I; Keyser, C; Francfort, H. P.; Crubezy, E; Samashev, Z; Ludes, B (2002). "Genetic analysis of human remains from a double inhumation in a frozen kurgan in Kazakhstan (Berel site, Early 3rd Century BC)". International journal of legal medicine. 116 (5): 304–8. PMID 12376844. doi:10.1007/s00414-002-0295-x (inactive 2017-01-16).

- 1 2 Kim, Kijeong; Brenner, Charles H.; Mair, Victor H.; Lee, Kwang-Ho; Kim, Jae-Hyun; Gelegdorj, Eregzen; Batbold, Natsag; Song, Yi-Chung; Yun, Hyeung-Won; Chang, Eun-Jeong; Lkhagvasuren, Gavaachimed; Bazarragchaa, Munkhtsetseg; Park, Ae-Ja; Lim, Inja; Hong, Yun-Pyo; Kim, Wonyong; Chung, Sang-In; Kim, Dae-Jin; Chung, Yoon-Hee; Kim, Sung-Su; Lee, Won-Bok; Kim, Kyung-Yong (2010). "A western Eurasian male is found in 2000-year-old elite Xiongnu cemetery in Northeast Mongolia". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 142 (3): 429–40. PMID 20091844. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21242.

- ↑ Xue, Y.; Zerjal, T; Bao, W; Zhu, S; Shu, Q; Xu, J; Du, R; Fu, S; Li, P; Hurles, M. E.; Yang, H; Tyler-Smith, C (2005). "Male Demography in East Asia: A North-South Contrast in Human Population Expansion Times". Genetics. 172 (4): 2431–9. PMC 1456369

. PMID 16489223. doi:10.1534/genetics.105.054270.

. PMID 16489223. doi:10.1534/genetics.105.054270. - ↑ Psarras, Sophia-Karin (2003). "Han and Xiongnu: A Reexamination of Cultural and Political Relations (I)". Monumenta Serica. 51: 55–236. JSTOR 40727370.

- ↑ Machulla, H.K.G.; Batnasan, D.; Steinborn, F.; Uyar, F.A.; Saruhan-Direskeneli, G.; Oguz, F.S.; Carin, M.N.; Dorak, M.T. (2003). "Genetic affinities among Mongol ethnic groups and their relationship to Turks". Tissue Antigens. 61 (4): 292–9. PMID 12753667. doi:10.1034/j.1399-0039.2003.00043.x.

- ↑ Shou, Wei-Hua; Qiao, En-Fa; Wei, Chuan-Yu; Dong, Yong-Li; Tan, Si-Jie; Shi, Hong; Tang, Wen-Ru; Xiao, Chun-Jie (2010). "Y-chromosome distributions among populations in Northwest China identify significant contribution from Central Asian pastoralists and lesser influence of western Eurasians". Journal of Human Genetics. 55 (5): 314–22. PMID 20414255. doi:10.1038/jhg.2010.30.

- ↑ Cruciani, Fulvio; La Fratta, Roberta; Torroni, Antonio; Underhill, Peter A.; Scozzari, Rosaria (2006). "Molecular dissection of the Y chromosome haplogroup E-M78 (E3b1a): A posteriori evaluation of a microsatellite-network-based approach through six new biallelic markers". Human Mutation. 27 (8): 831–2. PMID 16835895. doi:10.1002/humu.9445.

- ↑ Gokcumen, Omer (2008). Ethnohistorical and genetic survey of four Central Anatolian settlements (Thesis). University of Pennsylvania. OCLC 857236647.

- ↑ Yunusbayev, Bayazit; Metspalu, Mait; Metspalu, Ene; Valeev, Albert; Litvinov, Sergei; Valiev, Ruslan; Akhmetova, Vita; Balanovska, Elena; Balanovsky, Oleg; Turdikulova, Shahlo (2015). "The Genetic Legacy of the Expansion of Turkic-Speaking Nomads across Eurasia". PLoS Genetics. 11 (4): e1005068. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005068.

- ↑ Varzari, Alexander; Stephan, Wolfgang; Stepanov, Vadim; Raicu, Florina; Cojocaru, Radu; Roschin, Yuri; Glavce, Cristiana; Dergachev, Valentin; Spiridonova, Maria; Schmidt, Horst D.; Weiss, Elisabeth (2007). "Population history of the Dniester–Carpathians: Evidence from Alu markers". Journal of Human Genetics. 52 (4): 308–16. PMID 17387576. doi:10.1007/s10038-007-0113-x.

- ↑ Di Benedetto, G; Ergüven, A; Stenico, M; Castrì, L; Bertorelle, G; Togan, I; Barbujani, G (2001). "DNA diversity and population admixture in Anatolia". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 115 (2): 144–56. PMID 11385601. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1064.

- 1 2 Caner Berkman, Ceren; Togan, İnci (2009). "The Asian contribution to the Turkish population with respect to the Balkans: Y-chromosome perspective". Discrete Applied Mathematics. 157 (10): 2341–8. doi:10.1016/j.dam.2008.06.037.

- ↑ Berkman, Ceren (September 2006). Comparative Analyses for the Central Asian Contribution to Anatolian Gene Pool with Reference to Balkans (PDF) (PhD Thesis). Middle East Technical University. p. 98.

- ↑ Behar, Doron M.; Yunusbayev, Bayazit; Metspalu, Mait; Metspalu, Ene; Rosset, Saharon; Parik, Jüri; Rootsi, Siiri; Chaubey, Gyaneshwer; Kutuev, Ildus; Yudkovsky, Guennady; Khusnutdinova, Elza K.; Balanovsky, Oleg; Semino, Ornella; Pereira, Luisa; Comas, David; Gurwitz, David; Bonne-Tamir, Batsheva; Parfitt, Tudor; Hammer, Michael F.; Skorecki, Karl; Villems, Richard (2010). "The genome-wide structure of the Jewish people". Nature. 466 (7303): 238–42. Bibcode:2010Natur.466..238B. PMID 20531471. doi:10.1038/nature09103.