Berlin Conference

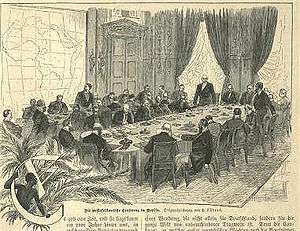

The Berlin Conference of 1884–85, also known as the Congo Conference (German: Kongokonferenz) or West Africa Conference (Westafrika-Konferenz),[1] regulated European colonization and trade in Africa during the New Imperialism period, and coincided with Germany's sudden emergence as an imperial power. The conference was organized by Otto von Bismarck, first Chancellor of Germany, its outcome, the General Act of the Berlin Conference, can be seen as the formalization of the Scramble for Africa. The conference ushered in a period of heightened colonial activity by European powers, which eliminated or overrode most existing forms of African autonomy and self-governance.[2]

Early history of the Berlin Conference

Before the conference, European diplomacy treated African indigenous people in the same manner as the New World natives, forming trading relationships with the indigenous chiefs. By the mid-19th century, Europeans considered Africa to be disputed territory ripe for exploration, trade, and settlement by their colonists. With the exception of trading posts along the coasts, the continent was essentially ignored.

In 1876, King Leopold II of Belgium, who had previously founded the International African Society in 1876, invited Henry Morton Stanley to join him in researching and 'civilising' the continent. In 1878, the International Congo Society was also formed, with more economic goals, but still closely related to the former society. Léopold secretly bought off the foreign investors in the Congo Society, which was turned to imperialistic goals, with the African Society serving primarily as a philanthropic front.

From 1878 to 1885, Stanley returned to the Congo, not as a reporter but as an envoy from Léopold with the secret mission to organize what would become known as the Congo Free State. French intelligence had discovered Leopold's plans, and France quickly engaged in its own colonial exploration. French naval officer Pierre de Brazza was dispatched to central Africa, traveled into the western Congo basin, and raised the French flag over the newly founded Brazzaville in 1881, in what is currently the Republic of Congo. Finally, Portugal, which already had a long, but essentially abandoned colonial Empire in the area through the mostly defunct proxy state Kongo Empire, also claimed the area. Its claims were based on old treaties with Spain and the Roman Catholic Church. It quickly made a treaty on 26 February 1884 with its former ally, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, to block off the Congo Society's access to the Atlantic.

By the early 1880s, due to many factors including diplomatic maneuvers, subsequent colonial exploration, and recognition of Africa's abundance of valuable resources such as gold, timber, land, and markets, European interest in the continent had increased dramatically. Stanley's charting of the Congo River Basin (1874–77) removed the last terra incognita from European maps of the continent, and delineating the areas of British, Portuguese, French, and Belgian control. The powers raced to push these rough boundaries to their furthest limits and eliminate any potential local minor powers which might prove troublesome to European competitive diplomacy.

France moved to take over Tunisia, one of the last of the Barbary Pirate states, under the pretext of another piracy incident. French claims by Pierre de Brazza were quickly solidified with French taking control of today's Republic of the Congo in 1881 and Guinea in 1884. Italy became part of the Triple Alliance, upsetting Bismarck's carefully laid plans with the state and forcing Germany to become involved in Africa. In 1882, realizing the geopolitical extent of Portuguese control on the coasts, but seeing penetration by France eastward across Central Africa toward Ethiopia, the Nile, and the Suez Canal, Britain saw its vital trade route through Egypt and its Indian Empire threatened.

Under the pretext of the collapsed Egyptian financing and a subsequent riot, in which hundreds of Europeans and British subjects were murdered or injured, the United Kingdom intervened in nominally Ottoman Egypt. Through it, the UK also ruled over the Sudan and what would later become British Somaliland.

Conference

Owing to the European race for colonies, Germany started launching expeditions of its own, which frightened both British and French statesmen. Hoping to quickly soothe this brewing conflict, King Leopold II convinced France and Germany that common trade in Africa was in the best interests of all three countries. Under support from the British and the initiative of Portugal, Otto von Bismarck, German Chancellor, called on representatives of 13 nations in Europe as well as the United States to take part in the Berlin Conference in 1884 to work out joint policy on the African continent.

Whilst the number of plenipotentiaries varied per nation,[3] the following 14 countries did send representatives to attend the Berlin Conference and sign the subsequent Berlin Act:

-

.svg.png) Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary -

.svg.png) Belgium

Belgium -

Denmark

Denmark -

France

France -

German Empire

German Empire -

_crowned.svg.png) Italy

Italy -

Netherlands

Netherlands -

Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Empire -

.svg.png) Portugal

Portugal -

.svg.png) Russian Empire

Russian Empire -

.svg.png) Spain

Spain -

.svg.png) Sweden-Norway

Sweden-Norway -

United Kingdom

United Kingdom -

United States - though the United States reserved the right to decline or to accept the conclusions of the Conference.[4]

United States - though the United States reserved the right to decline or to accept the conclusions of the Conference.[4]

The conference was convened on Saturday, November 15, 1884, at Bismarck's official residence on Wilhelmstrasse (site of the Congress of Berlin six years earlier).[5] Bismarck accepted the chairmanship. The British representative was Sir Edward Malet (Ambassador to the German Empire). Henry Morton Stanley attended as a U.S. delegate.[5]

General Act

The General Act fixed the following points:

- To gain public acceptance, the conference resolved to end slavery by African and Islamic powers. Thus, an international prohibition of the slave trade throughout their respected spheres was signed by the European members. Because of this point the writer Joseph Conrad sarcastically referred to the conference as "the International Society for the Suppression of Savage Customs" in his novella Heart of Darkness.[6]

- The Congo Free State was confirmed as the private property of the Congo Society, which supported Leopold's promises to keep the country open to all European investment. The territory of today's Democratic Republic of the Congo, some two million square kilometers, was confirmed by the European powers as essentially the property of Léopold II (but later it was organized as a Belgian colony under state administration).

- The 14 signatory powers would have free trade throughout the Congo Basin as well as Lake Malawi, and east of this in an area south of 5° N.

- The Niger and Congo rivers were made free for ship traffic.

- A Principle of Effectivity (based on "effective occupation", see below) was introduced to stop powers setting up colonies in name only.

- Any fresh act of taking possession of any portion of the African coast would have to be notified by the power taking possession, or assuming a protectorate, to the other signatory powers.

- Definition of regions in which each European power had an exclusive right to "pursue" the legal ownership of land (legal in the eyes of the other European powers).[7]:44

The first reference in an international act to the obligations attaching to "spheres of influence" is contained in the Berlin Act.

Principle of Effective Occupation

The principle of effective occupation stated that powers could acquire rights over colonial lands only if they possessed them or had "effective occupation": in other words, if they had treaties with local leaders, if they flew their flag there, and if they established an administration in the territory to govern it with a police force to keep order. The colonial power could also make use of the colony economically. This principle became important not only as a basis for the European powers to acquire territorial sovereignty in Africa, but also for determining the limits of their respective overseas possessions, as effective occupation served in some instances as a criterion for settling disputes over the boundaries between colonies. But, as the Berlin Act was limited in its scope to the lands that fronted on the African coast, European powers in numerous instances later claimed rights over lands in the interior without demonstrating the requirement of effective occupation, as articulated in Article 35 of the Final Act.

At the Berlin Conference of 1885, the scope of the Principle of Effective Occupation was heavily contested between Germany and France. The Germans, who were new to the continent of Africa, essentially believed that as far as the extension of power in Africa was concerned, no colonial power should have any legal right to a territory, unless the state exercised strong and effective political control, and if so, only for a limited period of time, essentially an occupational force only. However, Britain's view was that Germany was a latecomer to the continent, and was assumptively unlikely to gain any new possessions, apart from already occupied territories, which were swiftly proving to be more valuable than British-occupied territories. Given that logic, it was generally assumed by Britain and France that Germany had an interest in embarrassing the other European powers on the continent and forcing them to give up their possessions if they could not muster a strong political presence. On the other side, the United Kingdom (UK) had large territorial "possessions" on the continent and wanted to keep them while minimising its responsibilities and administrative costs. In the end, the British view prevailed.

The disinclination to rule what the Europeans had "conquered" is apparent throughout the protocols of the Berlin Conference, but especially in "The Principle of Effective Occupation." In line with Germany and Britain's opposing views, the powers finally agreed that this could be established by a European power establishing some kind of base on the coast, from which it was free to expand into the interior. The Europeans did not believe that the rules of occupation demanded European hegemony on the ground. The Belgians originally wanted to include that "effective occupation" required provisions that "cause peace to be administered", but other powers, specifically Britain and France, had that amendment struck out of the final document.

This principle, along with others that were written at the Conference allowed the Europeans to "conquer" Africa while doing as little as possible to administer or control it. The Principle of Effective Occupation did not apply so much to the hinterlands of Africa at the time of the conference. This gave rise to "hinterland theory," which basically gave any colonial power with coastal territory the right to claim political influence over an indefinite amount of inland territory. Since Africa was irregularly shaped, this theory caused problems and was later rejected.[8]

Agenda

- Portugal–Britain: The Portuguese government presented a project, known as the "Pink Map" (also called the "Rose-Colored Map"), in which the colonies of Angola and Mozambique were united by co-option of the intervening territory (land that later became Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Malawi.) All of the countries attending the conference, except for the United Kingdom, endorsed Portugal's ambitions. A little more than five years later, in 1890, the British government, in breach of the Treaty of Windsor (and of the Treaty of Berlin itself), issued an ultimatum demanding that the Portuguese withdraw from the disputed area.

- France–Britain: A line running from Say in Niger to Maroua, on the north-east coast of Lake Chad determined what part belonged to whom. France would own territory to the north of this line, and the United Kingdom would own territory to the south of it. The Nile Basin would be British, with the French taking the basin of Lake Chad. Furthermore, between the 11th and 15th degrees latitude, the border would pass between Ouaddaï, which would be French, and Darfur in Sudan, to be British. In reality, a no man's land 200 kilometres wide was put in place between the 21st and 23rd meridians.

- France–Germany: The area to the north of a line formed by the intersection of the 14th meridian and Miltou was designated French, that to the south being German.

- Britain–Germany: The separation came in the form of a line passing through Yola, on the Benoué, Dikoa, going up to the extremity of Lake Chad.

- France–Italy: Italy was to own what lies north of a line from the intersection of the Tropic of Cancer and the 17th meridian to the intersection of the 15th parallel and 21st meridian.

Consequences

Belgium Germany Spain France

Britain Italy Portugal Independent

The conference provided an opportunity to channel latent European hostilities towards one another outward, provide new areas for helping the European powers expand in the face of rising American, Russian, and Japanese interests, and form constructive dialogue for limiting future hostilities. For Africans, colonialism was introduced across nearly all the continent. When African independence was regained after World War II, it was in the form of fragmented states.[9]

The Scramble for Africa sped up after the Conference, since even within areas designated as their sphere of influence, the European powers still had to take possession under the Principle of Effectivity. In central Africa in particular, expeditions were dispatched to coerce traditional rulers into signing treaties, using force if necessary, as for example in the case of Msiri, King of Katanga, in 1891. Bedouin and Berber ruled states in the Sahara and Sub-Sahara were overrun by the French in several wars by the beginning of World War I. The British moved up from South Africa and down from Egypt conquering Arabic states such as the Mahdist State and the Sultanate of Zanzibar and, (having already defeated the Zulu Kingdom in South Africa, in 1879), moving on to subdue and dismantle the independent Boer republics of Transvaal and Orange Free State.

Within a few years, Africa was at least nominally divided up south of the Sahara. By 1895, the only independent states were:

-

Morocco, involved in colonial conflicts with Spain and France, who conquered the nation in the 20th century.

Morocco, involved in colonial conflicts with Spain and France, who conquered the nation in the 20th century. -

Liberia, founded with the support of the United States for returned slaves;

Liberia, founded with the support of the United States for returned slaves; -

.svg.png) Ethiopian Empire, the only free native state, which fended off Italian invasion from Eritrea in what is known as the First Italo-Abyssinian War of 1889–96.

Ethiopian Empire, the only free native state, which fended off Italian invasion from Eritrea in what is known as the First Italo-Abyssinian War of 1889–96. - Majeerteen Sultanate, the sultanate was founded in the early 18th century, it was annexed by Italy in the 20th century.

- Sultanate of Hobyo, the sultanate was carved out of the former Majeerteen Sultanate and ruled northern Somalia until the 20th century, when it was conquered by Italy.

The following states lost their independence to the British Empire roughly a decade after (see below for more information):

-

Orange Free State, a Boer republic founded by Dutch settlers;

Orange Free State, a Boer republic founded by Dutch settlers; -

South African Republic (Transvaal), also a Boer republic;

South African Republic (Transvaal), also a Boer republic;

By 1902, 90% of all the land that makes up Africa was under European control. The large part of the Sahara was French, while after the quelling of the Mahdi rebellion and the ending of the Fashoda crisis, the Sudan remained firmly under joint British–Egyptian rulership with Egypt being under British occupation before becoming a British protectorate in 1914.

The Boer republics were conquered by the United Kingdom in the Boer war from 1899 to 1902. Morocco was divided between the French and Spanish in 1911, and Libya was conquered by Italy in 1912. The official British annexation of Egypt in 1914 ended the colonial division of Africa.

See also

References

- ↑ "Berlin West Africa Conference", Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ Ajala, Adekunle (1983), "The Nature of African Boundaries", Africa Spectrum, Institute of African Affairs at GIGA, Hamburg, 18 (2): 177–189, JSTOR 40174114,

Kwame Nkrumah once made the point that the Berlin Conference of 1884/85 was responsible for "the old carve-up of Africa". Other writers have also laid the blame for "the partition of Africa" on the doors of the Berlin Conference. But William Roger Louis holds a contrary view, although he conceded that "the Berlin Act did have a relevance to the course of the partition" of Africa.

- ↑ 140.112.142.79/publish/pdfs/22/22_08.pdf

- ↑ http://lril.oxfordjournals.org/content/3/1/31.full

- 1 2 Louis, Wm. Roger. Ends of British Imperialism: The Scramble for Empire, Suez, and Decolonization. I.B. Tauris, May, 2007

- ↑ "Historical Context: Heart of Darkness." EXPLORING Novels, Online Edition. Gale, 2003. Discovering Collection. (subscription required)

- ↑ Olusoga, David; Erichsen, Casper W. (2010). The Kaisers's Holocaust: Germany's Forgotten Genocide and the Colonial Roots of Nazism. London, UK: Faber and Faber. p. 394. ISBN 978-0-571-23141-6.

- ↑ Herbst, Jeffrey. States and Power in Africa. Ch. 3 p71-72

- ↑ de Blij, H.J.; Muller, Peter O. (1997). Geography: Realms, Regions, and Concepts. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 340.

Citations

- Tapiwa Michael Njitimana, Erald Yomisi (2013)The Demise Of Germany

- Chamberlain, Muriel E. (1999). The Scramble for Africa. London: Longman, 1974, 2nd ed. ISBN 0-582-36881-2.

- Crowe, Sybil E. (1942). The Berlin West African Conference, 1884–1885. New York: Longmans, Green. ISBN 0-8371-3287-8 (1981, New ed. edition).

- Förster, Stig, Wolfgang J. Mommsen, and Ronald Edward Robinson (1989). Bismarck, Europe, and Africa: The Berlin Africa Conference 1884–1885 and the Onset of Partition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-920500-0.

- Hochschild, Adam (1999). King Leopold's Ghost. ISBN 0-395-75924-2.

- Nuzzo, Luigi. "Colonial Law," in: European History Online (EGO), published by the Leibniz Institute of European History (IEG), Mainz 2012-04-16. URL: http://www.ieg-ego.eu/nuzzol-2011-en URN: urn:nbn:de:0159-2012041215 [2012-04-16].

- Petringa, Maria (2006). Brazza, A Life for Africa. ISBN 978-1-4259-1198-0.

Further reading

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Berlin Conference (1884). |

- Geography.about.com - Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 to Divide Africa.

- "The Berlin Conference", BBC In Our Time