Common loon

| Common loon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult in breeding plumage in Wisconsin, United States | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Gaviiformes |

| Family: | Gaviidae |

| Genus: | Gavia |

| Species: | G. immer |

| Binomial name | |

| Gavia immer (Brunnich, 1764) | |

| |

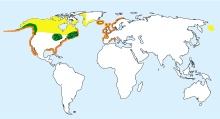

| Distribution of G. immer. Not shown is the eastern part of the wintering range, which encompasses lakes and coastal areas down to Central Europe. Breeding range Year-round range Wintering range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Gavia imber | |

The common loon (Gavia immer) is a large member of the loon, or diver, family of birds. The species is known as the great northern diver in Eurasia (another former name, great northern loon, was a compromise proposed by the International Ornithological Committee). It has a broad black head and bill, white underparts, and a checkered black-and-white mantle. During breeding season, it lives on lakes and other waterways in Canada, the northern United States (including Alaska), as well as in southern parts of Greenland, and in Iceland to the east. It winters as far south as Mexico, and as far east as northwestern Europe. It can also be found along the Atlantic coast from Newfoundland to the Gulf of Mexico.

The common loon eats a wide range of animal prey including fish, crustaceans, insect larvae, mollusks, and occasionally aquatic plant life. It swallows most of its prey underwater, where it is caught, but some larger prey is first brought to the surface. It is a monogamous breeder. Both members of the pair build a large nest out of dead marsh grasses and other plants formed into a mound along the vegetated shores of lakes. A single clutch is laid each year of one or two olive-brown oval eggs with dark brown spots. Incubation takes 24 to 25 days and fledging takes 70 to 77 days. Both parents take turns incubating the eggs and both feed the young. The chicks are capable of diving underwater and can typically fly at 10 to 11 weeks old; they leave the breeding ground before ice formation in the fall.

The common loon has been rated as a species of least concern on the IUCN Red List of Endangered Species (IUCN). It is also listed under Appendix II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species, Article I under the EU Birds Directive, and in 83 Special Protection Areas in the EU Natura 2000 network. It is one of the species to which the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA) is applied. The USDA National Forest Service has designated the common loon a species of special status.

Taxonomy

The common loon is one of five loon species that make up the genus Gavia, the only genus of the family Gaviidae and order Gaviiformes. Its closest relative is another large black-headed species, the yellow-billed loon, or white-billed diver (Gavia adamsii).[2]

The genus name Gavia was the Latin term for the smew (Mergellus albellus). This small sea-duck is quite unrelated to loons and just happens to be another black-and-white seabird that swims and dives for fish. It is unlikely that the ancient Romans had much knowledge of loons, which are limited to more northern latitudes, and since the end of the last glacial period seem to have appeared only as rare winter migrants in the Mediterranean region.[3][4] The specific name immer is derived from North Germanic names for the bird such as modern Icelandic "himbrimi".[5] The term may be related to Swedish immer and emmer: the grey or blackened ashes of a fire (referring to the loon's dark plumage); or to Latin immergo, to immerse, and immersus, submerged.[6]

The European name "diver" comes from the bird's habit of catching fish by swimming calmly along the surface and then abruptly plunging into the water. The North American name "loon" may be a reference to the bird's clumsiness on land, and derived from Scandinavian words for lame, such as Icelandic lúinn and Swedish lam. Another possible derivation is from the Norwegian word lom for these birds, which comes from Old Norse lómr, possibly cognate with English "lament", referring to the characteristic plaintive sound of the loon.[7] The scientific name Gavia refers to seabirds in general.[8] An old colloquial name from New England was call-up-a-storm, as its noisy cries supposedly foretold stormy weather.[9] The Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation people of Old Crow, Yukon, call it Ttretetere.[10]

Description

.jpg)

Adults can range from 71 to 91 cm (28 to 36 in) in length[11] with a 120 to 148 cm (47 to 58 in) wingspan, slightly smaller than the similar yellow-billed loon.[12] Their weight can vary from 3.2 to 4.1 kg (7.1 to 9.0 lb).[11] On average, a common loon is about 81 cm (32 in) long, has a wingspan of 136 cm (54 in), and weighs about 4.1 kg (9.0 lb). Adults in breeding plumage have a broad black head and bill, white underparts, and a checkered black-and-white mantle.[13] The neck is encircled with a characteristic black ring[13] and two white necklaces.[11] The eyes are red.[11] Non-breeding plumage is brownish with a dark neck and head,[13] with a bump on the forehead.[13] The foreneck is whitish and may sometimes reveal a shadowy trace of the neck ring or a pale collar.[13] The eyelids are pale.[13]

The heavy dagger-like bill[11] is evenly tapered and grayish, sometimes having a black tip.[13] The bill colour and angle distinguish this species from the yellow-billed loon. The neck is short and thick.[13] They swim very low in the water, with sometimes only their head held above and horizontal to water.[14][11] They must run across the water surface to get in flight. During flight, their head is slightly lower than their body, with their feet trailing behind.[11]

Juvenile birds often have a dark, brownish-grey nape which may look darker than the pale-edged black feathers.[15] They have a dark grey to black head, neck, and upperparts, with white throat, cheeks, and underparts.[11] During the first winter, the bill shape of young common loons may not be as fully developed as that of the adult.[15]

Common loons have a bone structure made up of a number of solid bones (unlike normally hollow avian bones), which add weight but help in diving.[16]

Distribution and habitat

.jpg)

During their breeding season in spring and summer, most common loons live on lakes and other waterways in Canada and the northern United States, as well as in southern parts of Greenland, in Iceland to the east, and in Alaska to the west.[17][18] Their summer habitat ranges from wooded lakes to tundra ponds. The lakes must be large enough for take-off (flying), and must also provide a high population of small fish.[19] Clear water is necessary so that they can see fish to prey on. As protection from predators, common loons favor lakes with islands and coves.[20] They are rare visitors to the Arctic coast.[21]

Common loons, during their winter migration, can be seen as far south as Baja California, Sonora, northern Sinaloa, southern Texas, rarely northern Tamaulipas, and east as far as northwestern Europe from Finland to Portugal, as well as the western Mediterranean.[22][23][1] They are spread throughout the Atlantic coast from Newfoundland to the Gulf of Mexico.[24] They usually winter along the North American coasts and on inland lakes, bays, inlets, and streams,[18][25] migrating to the nearest body of water that will not freeze over in the winter: western Canadian loons to the Pacific, Great Lakes loons to the Gulf of Mexico region, eastern Canadian loons to the Atlantic, and some loons to large inland lakes and reservoirs.[20] They appear in most of the inland waters of the United States. The South Carolina coast, the Gulf coast adjacent to the Florida panhandle, and the Atlantic seaboard from Massachusetts to Maine have some of the highest concentrations of common loons.[18]

Behaviour

.jpg)

The common loon is an expert fisher, catching its prey underwater by diving as deep as 60 m (200 ft).[16] It can remain underwater for as long as 3 minutes.[26] With its large webbed feet, the common loon is an efficient predator, powerful swimmer, and adroit diver. It needs a long distance to gain momentum for take-off, and is ungainly on land. Its clumsiness on land is due to the legs being positioned at the rear of the body; this is ideal for diving but not well-suited for walking. When it lands on water, it skims along on its belly to slow down, rather than on its feet, as they are set too far back. The common loon swims gracefully on the surface, dives as well as any flying bird, and flies competently for hundreds of kilometres in migration. It flies with its neck outstretched, usually calling a particular tremolo that can be used to identify a flying loon. Its flying speed is as much as 120 km/h (75 mph) during migration.[16] Its call has been alternately called "haunting", "beautiful", and "thrilling".[27]

Feeding

Fish account for about 80% of the diet of the common loon.[28] It forages on fish of up to 10 inches in length, including minnows, suckers, gizzard shad, rock cod, alewife, northern pike, whitefish, sauger, brown bullhead, pumpkinseed, burbot, walleye, bluegill, white crappie, black crappie, rainbow smelt, and killifish.[19][28] Young loons typically eat small minnows, and sometimes insects and fragments of green vegetation.[17][29] Freshwater diets primarily consist of pike, perch, sunfish, trout, and bass; saltwater diets primarily consist of rock fish, flounder, sea trout, herring, Atlantic croaker and Gulf silverside.[29][20] When there is either a lack of fish or an inability to catch fish, it preys on crustaceans, crayfish, snails, leeches, insect larvae, mollusks, frogs, and occasionally aquatic plant life.[20][29] It has also been known to forage on ducklings.[29]

The common loon uses its powerful hind legs to propel its body underwater at high speed to catch its prey, which it then swallows headfirst. If the fish attempts to evade the common loon, the bird chases it down with excellent underwater maneuverability due to its tremendously strong legs.[20] Most prey are swallowed underwater, where they are caught, but some larger prey are first brought to the surface.[17] It is a visual predator, so it is essential to hunting success that the water is clear.[17]

Breeding

Common loons mate monogamously and annually. They begin breeding at two years of age.[30] Copulation takes place ashore, often on the nest site, repeated daily until the eggs are laid. The preceding courtship is very simple: mutual bill-dipping and dives.[31] The displays towards strangers such as bow-jumping (an alternation of fencing and bill-dipping postures[32]) and rushing (running "along the surface with its wings either folded or half-extended and flapping at about the same speed as when taking off"[33]) are often misinterpreted as courtship.[17]

Nesting typically begins in early May.[34] Both the male and the female build the nest together in May or early June over the course of a week.[20] The pair of mates claims a breeding territory of 60 to 200 acres and patrols it frequently, defending and marking the territory both physically and vocally. The nest is about 56 cm (22 in) wide and is constructed out of dead marsh grasses and other indigenous plants, and formed into a mound along the vegetated coasts of lakes greater than 9 acres and at elevations of 5,000 to 9,000 ft (1,500 to 2,700 m).[20][11] After a week of construction in late spring, one parent climbs on top to mold the nest to the shape of its body.[20] Nest sites typically resemble those on which the parents were hatched. Instead of avoiding acidity and poor water quality, the parents risk success for better survival chances and choose lakes that yield similar fish to their regular diet.[35] These nest sites are often reused annually, and studies suggest that these renesting attempts are more likely to succeed than the initial attempt.[36] Based on a number of studies, nesting success averages about 40%.[37]

In a clutch, there are one or two olive-brown oval eggs with dark brown spots.[11] Incubation takes 24 to 25 days,[30] and both the male and female parents take turns incubating the eggs.[17] Usually, only one brood is laid.[20] The eggs are laid in late May or June.[30] They are about 88 mm (3.5 in) long and 55 mm (2.2 in) wide.[20] The eggs are laid at an interval of one to three days,[28] and hatch asynchronously.[37] The newly born chicks are sooty black and have a white belly. Within hours of hatching, the young begin to leave the nest with the parents, swimming and sometimes riding on one parent’s back.[20] They are capable of diving underwater in the next few days and can typically fly at 10 to 11 weeks old.[19] Fledging takes 70 to 77 days.[30] Both adults feed the chicks live prey from hatching to fledging and as they grow, they become able to forage for themselves. If food is scarce, the young may fight intensely, and often only one young survives. The chicks leave the breeding ground before ice formation in the fall.[11]

Common loons have faced a decline in breeding range primarily due to hunting, predation, human destruction of habitat, contaminant exposure, and water-level fluctuations or flooding. Some environmentalists attempt to increase nesting success by mitigating the effects of some of these threats, namely terrestrial predation and water-level fluctuations, through the deployment of rafts and artificial nesting islands in the breeding territories of common loons.[38]

Vocalization

Common loons produce a variety of vocalizations, the most common of which are categorized into four main types: the tremolo, the yodel, the wail, and the hoot. Each of these calls communicates a distinct message. The frequency at which loons vocalize has been shown to vary based on time of day, weather, and season. They are most vocally active between mid-May and mid-June. The wail, yodel, and tremolo calls are sounded more frequently at night than during the day, and calls have also been shown to occur more frequently in cold temperatures and when there is little to no rain.[39]

|

Common loon tremolo call

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

The tremolo call—sometimes called the “laughing” call—is characterized by its short, wavering quality. Loons often use this call to signal distress or alarm caused by territorial disputes or perceived threats.[39] Loons also use the tremolo to communicate their presence to other loons when they arrive at a lake, often when they are flying overhead. It is the only vocalization used in flight.[40] The tremolo call has varying levels of intensity and can be identified as type I, II, or III. These levels correlate with a loon’s level of distress, and the types are differentiated by increasingly higher pitch frequencies added to the call.[41]

|

Male Common loon yodel call

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

The yodel is a long and complex call made only by male loons. It is used in the establishment of territorial boundaries and in territorial confrontations, and the length of the call corresponds with the loon's level of aggression.[42] Every male loon has a unique yodel, which changes if the loon changes territory.[20]

A loon’s wail is a long call consisting of up to three notes, and is often compared to a wolf’s howl. Loons use this call to communicate their location to other loons. The call is given back and forth between breeding pairs or an adult and their chick, either to maintain contact or in an attempt to move closer together after being separated.[40]

The hoot is a short, soft call and is another form of contact call. It is a more intimate call than the wail and is used exclusively between small family groups or flocks.[39] Loons hoot to let other family or flock members know where they are. This call is often heard when adult loons are summoning their chicks to feed.[40]

Nest predators and hazards

Common loon nests are usually placed on islands, where ground-based predators cannot normally access them. However, eggs and nestlings have been taken by gulls, corvids, raccoons, skunks, minks, foxes, snapping turtles, and large fish. Adults are not regularly preyed upon, but have been taken by sea otters (when wintering) and bald eagles.[43] Ospreys have been observed harassing common loons, more likely out of kleptoparasitism than predation.[44] When a predator approaches (either the loon's nest or the loon itself), common loons sometimes attack the predator by rushing at it and attempting to impale it through the abdomen or the back of the head or neck with its dagger-like bill.[45]

Status and conservation

Since 1998, the common loon has been rated as a species of least concern on the IUCN Red List of Endangered Species. This is because it has a large range: more than 20,000 km2 (7700 mi2). Its population trend is stable, and thought not to have declined by 30% over ten years or three generations, and thus is not a rapid enough decline to warrant a vulnerable rating. In addition, it also has a large population size.[1] The common loon is also listed under Appendix II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species, and in Article I under the EU Birds Directive.[1] It is one of the species to which the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA) is applied.[46] In Europe it appears in 20 Important Bird Areas (IBAs), including Ireland, Norway (Svalbard and mainland Norway), Iceland, Spain, and in the United Kingdom. It is also a listed species in 83 Special Protection Areas in the EU Natura 2000 network.[1] The USDA National Forest Service has designated the common loon a species of special status, and in the upper Great Lake regions of the Ottawa, Hiawatha, and Huron-Manistee national forests as a regional forester sensitive species.[47]

The common loon has disappeared from some lakes in eastern North America, and its breeding range has moved northward[48] due to the effects of acid rain and pollution, as well as lead poisoning from fishing sinkers and mercury contamination from industrial waste.[49] Artificial floating nesting platforms have been provided for loons in some lakes to reduce the impact of changing water levels due to dams and other human activities.[50] The common loon abandons lakes that fail to provide suitable nesting habitat due to shoreline development. It is endangered by personal watercraft and powerboats which may drown newly born chicks, wash eggs away, or swamp nests.[48] It is still considered an "injured" species in Alaska as a result of the Exxon Valdez oil spill.[47]

In popular culture

_(8574783618).jpg)

The common loon is well known in Canada, appearing on the one-dollar "loonie" coin and the previous series of $20 bills.[51] It is the provincial bird of Ontario.[52] It was designated the state bird of Minnesota in 1961,[53] and also appears on the Minnesota State Quarter.[54]

The voice and appearance of the common loon has made it prominent in several Native American tales. These include an Ojibwe story of a loon which created the world,[55] and a Micmac saga describing Kwee-moo, the loon who was a special messenger of Glooscap (Glu-skap), the tribal hero.[56] The tale of the loon's necklace was handed down in many versions among Pacific Coast peoples,[57] and native tribes of British Columbia believed that an excess of calls from this bird predicted rain, and even brought it.[58] Folk names for the common loon include big loon, call-up-a-storm, greenhead, hell-diver, walloon, black-billed loon, guinea duck, imber diver, ring-necked loon,[59] and ember-goose.[60]

The common loon is central to the plot of the children's novel Great Northern? by Arthur Ransome (in which it is referred to throughout as "great northern diver", with the obsolete scientific name Colymbus immer). The story is set in the Outer Hebrides, where the main characters—a group of children on holiday—notice a pair of divers apparently nesting there. Checking their bird book, they believe that these are great northern divers. However, these have not previously been seen to nest in northern Scotland, and so they ask for help from an ornithologist. He confirms that these birds are indeed the great northern; unfortunately, it soon transpires that he does not wish merely to observe, but wants to steal the eggs and add them to his collection, and to do this, he must first kill the birds. Published in 1947, the story is one where the conservationists are the eventual victors over the egg collector, at a time when the latter hobby was not widely considered to be harmful.[61]

In the 2016 Pixar movie Finding Dory, a somewhat bedraggled and dimwitted loon named Becky is persuaded to use a bucket to help two of the main characters, Nemo and Marlin, get into a marine life institute where the titular Dory is trapped.[62] Loons were also featured prominently in the 1981 film On Golden Pond.[63]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 BirdLife International (2012). "Gavia immer". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ Boertmann, D. (1990). "Phylogeny of the divers, family Gaviidae (Aves)". Steenstrupia. 16: 21–36.

- ↑ Brodkorb, Pierce (1964). "Catalogue of fossil birds. Part 1 (Archaeopterygiformes through Ardeiformes)". Bulletin of the Florida State Museum, Biological Sciences. 7 (4): 179–293.

- ↑ Arnott, W.G. (1964). "Notes on Gavia and Mergvs in Latin Authors. Classical Quarterly". (New Series). 14 (2): 249–262. doi:10.1017/s0009838800023806.

- ↑ Eriksson, Mats O.G. (2000). "Loons / divers - names -myths – Scandinavian perspective". Wetlands International Diver/Loon Specialist Group Newsletter (3): 5.

- ↑ Paul Johnsgard (1987) Diving Birds of North America. University of Nebraska Press. (Appendix 1)

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "loon". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- ↑ LoonWatch – Loon FAQs | Northland College Archived 13 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine.. Northland.edu. Retrieved on 2013-04-05.

- ↑ McAtee, W. L. (1951). "Bird Names Connected with Weather, Seasons, and Hours". American Speech. 26 (4): 268–278. doi:10.2307/453005.

- ↑ Irving, Laurence. (1958). "Naming of birds as part of the intellectual culture of Indians at Old Crow, Yukon Territory". Arctic. 11 (2): 117–122.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Spahr, Robin; Region, United States Forest Service Intermountain (1991). Threatened, endangered, and sensitive species of the Intermountain region. U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Region.

- ↑ Ryan, James M. (2009). Adirondack Wildlife: A Field Guide. UPNE. p. 114. ISBN 9781584657491.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Dunne, Pete (2013). Pete Dunne's Essential Field Guide Companion: A Comprehensive Resource for Identifying North American Birds. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 89. ISBN 0544135687.

- ↑ Icenoggle, Radd (2003). Birds in Place: A Habitat-based Field Guide to the Birds of the Northern Rockies. Farcountry Press. ISBN 9781560372417.

- 1 2 Kaufman, Kenn (2011). Kaufman Field Guide to Advanced Birding: Understanding what You See and Hear. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 171–172. ISBN 0547248326.

- 1 2 3 "The Uncommon Loon". Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kirschbaum, Kari, and Roberto J. Rodriguez. "Critter Catalog." BioKIDS. University of Michigan, 2002. Web. 30 Oct. 2015.

- 1 2 3 Forest Service, United States (2002). White River National Forest (N.F.), Land and Resource Management Plan: Environmental Impact Statement. p. 62.

- 1 2 3 "Common Loon." Audubon. N.p., 13 Nov. 2014. Web. 30 Oct. 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Anonymous. "All About Birds: Common Loon". Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Archived from the original on 2017-05-25. Retrieved 2017-08-06.

- ↑ 7, U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region (1988). Arctic National Wildlife Refuge: final comprehensive conservation plan, environmental impact statement, wilderness review, and wild river plans. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 7.

- ↑ Rappole, John H.; Blacklock, Gene W. (1994). Birds of Texas: A Field Guide. Texas A&M University Press. p. 14. ISBN 9780890965450.

- ↑ Peterson, Roger Tory; Chalif, Edward L. (March 1999). A Field Guide to Mexican Birds: Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 039597514X.

- ↑ DeGraaf, Richard M.; Yamasaki, Mariko (2001). New England Wildlife: Habitat, Natural History, and Distribution. UPNE. p. 80. ISBN 9780874519570.

- ↑ Bureau of Land Management, United States (1978). Marine mammal and seabird survey of the Southern California Bight area. National Technical Information Service, U.S. Department of Commerce. p. 849.

- ↑ Dan A. Tallman; David L. Swanson; Jeffrey S. Palmer (2002). Birds of South Dakota. Midstates/Quality Quick Print. p. 3. ISBN 0-929918-06-1.

- ↑ "Northwestern Ontario Bird Species - Common Loon". Borealforest.org. Retrieved 2011-10-24.

- 1 2 3 Sandilands, Al (2011). Birds of Ontario: Habitat Requirements, Limiting Factors, and Status: Volume 1–Nonpasserines: Loons through Cranes. UBC Press. p. 171. ISBN 9780774859431.

- 1 2 3 4 Eastman, John (2000). The Eastman Guide to Birds: Natural History Accounts for 150 North American Species. Stackpole Books. p. 219. ISBN 9780811745529.

- 1 2 3 4 Burton, Maurice; Burton, Robert (2002). International Wildlife Encyclopedia: Leopard - marten. Marshall Cavendish. p. 1486. ISBN 9780761472773.

- ↑ Sjölander, Sverre; G. Ågren. "The reproductive behaviour of the Common Loon". Wilson Bulletin 84:296-308. 1972.

- ↑ Johnsgard, Paul A. (1987). Diving birds of North America. University of Nebraska Press. p. 107.

- ↑ Sjolander, S.; Agren, G. (1976). "Reproductive Behavior of the Yellow-Billed Loon, Gavia Adamsii" (PDF). The Condor: 454–463.

- ↑ Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, United States (1996). Deerfield River Projects [VT, MA] : Deerfield River Project, Bear Swamp Pumped Storage Project, Gardners Falls Project, in the Deerfield River Basin: Environmental Impact Statement. pp. 3–27.

- ↑ "Animal Behaviour: Familiar Nest Sites Beat Better Lakes." Nature 499.7456 (2013): 8. Academic Search Complete. Web. 3 Nov. 2015.

- ↑ Windels, Steve K., et al. "Effects Of Water-Level Management On Nesting Success Of Common Loons." Journal Of Wildlife Management 77.8 (2013): 1626-1638. Environment Complete. Web. 3 Nov. 2015.

- 1 2 Eastman, John Andrew (1999). Birds of Lake, Pond, and Marsh: Water and Wetland Birds of Eastern North America. Stackpole Books. p. 216. ISBN 9780811726818.

- ↑ Desorbo, Christopher R., Kate M. Taylor, David E. Kramar, Jeff Fair, John H. Cooley, David C. Evers, William Hanson, Harry S. Vogel, and Jonathan L. Atwood. "Reproductive Advantages for Common Loons Using Rafts." Journal of Wildlife Management 71.4 (2007): 1206-213. Web.

- 1 2 3 Mennill, Daniel J. (2014). "Variation in the Vocal Behavior of Common Loons (Gavia mimer): Insights from Landscape-level Recordings". Waterbirds. 37 (sp1): 26–36. doi:10.1675/063.037.sp105.

- 1 2 3 "Vermont Fish & Wildlife". vtfishandwildlife.com. Vermont Fish and Wildlife.

- ↑ Barklow, William E. (1979). "Graded Frequency Variations of the Tremolo Call of the Common Loon (Gavia immer)". The Condor. 81 (1): 53–64. doi:10.2307/1367857.

- ↑ Mager III, John N.; Walcott, Charles; Piper, Walter H. (2012). "Male Common Loons Signal Greater Aggressive Motivation by Lengthening Territorial Yodels". Wilson Journal of Ornithology. 124 (1): 73–80. doi:10.1676/11-024.1.

- ↑ "ADW: Gavia immer: Information". Animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu. 2004-10-06. Retrieved 2011-10-24.

- ↑ "The Science Behind Algonquin's Animals - Research Projects - Common Loon". Sbaa.ca. Retrieved 2011-10-24.

- ↑ (Organization), Bird Observer (2004). Bird Observer. Bird Observer of Eastern Massachusetts. p. 203.

- ↑ "Gavia immer | AEWA". www.unep-aewa.org. Archived from the original on 2016-08-16. Retrieved 2017-07-12.

- 1 2 Tischler, Keren B. (September 2011). "Species Conservation Assessment for the Common Loon (Gavia immer) in the Upper Great Lakes" (PDF). USDA Forest Service, Eastern Region: 1–59.

- 1 2 Wiland, L. (2007). "Common Loon Conservation Status- Migratory Birds of the Great Lakes - University of Wisconsin Sea Grant Institute". seagrant.wisc.edu. Archived from the original on 2017-07-12. Retrieved 2017-07-12.

- ↑ Staff, Bowker; Publishing, R. R. Bowker; Bowker (1992). Environment Abstracts. Congressional Information Service. p. 1740.

- ↑ Upper Penobscot River Basin Project, Ripogenus Hydroelectric Project, Penobscot Mills Hydroelectric Project, Licensing, Piscataquis County, Penobscot County: Environmental Impact Statement. 1. 1996. pp. 4–45.

- ↑ Grzimek, Bernhard; Schlager, Neil (2003). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia, Volume 8: Birds I. Gale. p. 161. ISBN 9780787657840.

- ↑ Townsley, Frank (2016-03-10). British Columbia: Graced by Nature's Palette. FriesenPress. p. 191. ISBN 9781460277737.

- ↑ Carlson, Bruce M. (2007). Beneath the Surface: A Natural History of a Fisherman's Lake. Minnesota Historical Society. p. 159. ISBN 9780873515788.

- ↑ Koenig, Mike. "2005 S Minnesota State Quarter Proof Value | CoinTrackers". cointrackers.com. Archived from the original on 2017-07-06. Retrieved 2017-07-18.

- ↑ Svingen, Peder H.; Hertzel, Anthony X. (2000). The Common Loon: Population Status and Fall Migration in Minnesota. Minnesota Ornithologists' Union. p. 1.

- ↑ Alward, Brian Floyd (2007). Developing a precautionary warning for heavy metals using loons as a target species. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- ↑ Stallcup, Rich; Evens, Jules (2014). Field Guide to Birds of the Northern California Coast. University of California Press. p. 60. ISBN 9780520276161.

- ↑ Watch, Wisconsin Project Loon (1984). Annual Report. Sigurd Olson Environmental Institute. p. 7.

- ↑ Fróðskaparrit 53. Faroe University Press. p. 53. ISBN 9789991841038.

- ↑ Sandrock, James; Prior, Jean C. (March 2014). The Scientific Nomenclature of Birds in the Upper Midwest. University of Iowa Press. p. 63. ISBN 9781609382254.

- ↑ McGinnis, Molly (February 2004). "Totem Animals in Swallows & Amazons: Great Northern?". All Things Ransome. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- ↑ "Why Becky Is The Most Important Character In "Finding Dory"". Odyssey. 2016-07-06. Archived from the original on 2017-07-19. Retrieved 2017-07-19.

- ↑ On Golden Pond (1981), archived from the original on 2017-05-03, retrieved 2017-07-19

Further reading

- McIntyre, Judith W. (April 1989). "The Common Loon Cries for Help". National Geographic. Vol. 175 no. 4. pp. 510–524. ISSN 0027-9358. OCLC 643483454.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to the common loon. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Gavia immer |

- Common Loon stamps - bird-stamps.org

- Common loon (Gavia immer) - ARKive

- "Great Northern Diver (Gavia immer) media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Common loon photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)