Gap junction

| Gap junction | |

|---|---|

Gap junction | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | Gap+Junctions |

| TH | H1.00.01.1.02024 |

| FMA | 67423 |

A gap junction may also be called a nexus or macula communicans. When found in neurons or nerves it may also be called an electrical synapse. While an ephapse has some similarities to a gap junction, by modern definition the two are different.

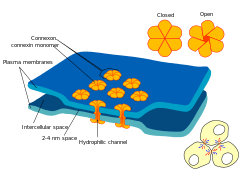

Gap junctions are a specialized intercellular connection between a multitude of animal cell-types.[1][2][3] They directly connect the cytoplasm of two cells, which allows various molecules, ions and electrical impulses to directly pass through a regulated gate between cells.[4][5]

One gap junction channel is composed of two connexons (or hemichannels), which connect across the intercellular space.[4][5][6] Gap junctions are analogous to the plasmodesmata that join plant cells.[7]

Gap junctions occur in virtually all tissues of the body, with the exception of adult fully developed skeletal muscle and mobile cell types such as sperm or erythrocytes. Gap junctions, however, are not found in simpler organisms such as sponges and slime molds.

Structure

In vertebrates, gap junction hemichannels are primarily homo- or hetero-hexamers of connexin proteins. Invertebrate gap junctions comprise proteins from the innexin family. Innexins have no significant sequence homology with connexins.[8] Though differing in sequence to connexins, innexins are similar enough to connexins to state that innexins form gap junctions in vivo in the same way connexins do.[9][10][11] The recently characterized pannexin family,[12] which was originally thought to form inter-cellular channels (with an amino acid sequence similar to innexins[13]), in fact functions as a single-membrane channel that communicates with the extracellular environment, and has been shown to pass calcium and ATP.[14]

At gap junctions, the intercellular space is between 2 and 4 nm[6] and unit connexons in the membrane of each cell are aligned with one another.[15]

Gap junction channels formed from two identical hemichannels are called homotypic, while those with differing hemichannels are heterotypic. In turn, hemichannels of uniform connexin composition are called homomeric, while those with differing connexins are heteromeric. Channel composition is thought to influence the function of gap junction channels.

Before innexins and pannexins were well characterized, the genes coding for connexin gap junction channels was classified in one of three groups, based on gene mapping and sequence similarity: A, B and C (for example, GJA1, GJC1).[16][17][18] However, connexin genes do not code directly for the expression of gap junction channels; genes can produce only the proteins that make up gap junction channels. An alternative naming system based on this protein's molecular weight is also popular (for example: connexin43=GJA1, connexin30.3=GJB4).

Levels of organization

- DNA to RNA to Connexin protein.

- One connexin protein has four transmembrane domains

- 6 Connexins create one Connexon (hemichannel). When different connexins join together to form one connexon, it is called a heteromeric connexon

- Two hemichannels, joined together across a cell membrane comprise a Gap Junction channel.

When two identical connexons come together to form a Gap junction channel, it is called a homotypic GJ channel. When one homomeric connexon and one heteromeric connexon come together, it is called a heterotypic gap junction channel. When two heteromeric connexons join, it is also called a heterotypic Gap Junction channel. - Several gap junction channels (hundreds) assemble within a macromolecular complex called a gap junction plaque.

Properties of connexon channel pairs

- Allows for direct electrical communication between cells, although different connexin subunits can impart different single channel conductances, from about 30 pS to 500 pS.

- Allows for chemical communication between cells, through the transmission of small second messengers, such as inositol triphosphate (IP

3) and calcium (Ca2+

),[7] although different connexin subunits can impart different selectivity for particular small molecules. - In general, allows transmembrane movement of molecules smaller than 485 Daltons[20] (1,100 Daltons through invertebrate gap junctions[21]), although different connexin subunits may impart different pore sizes and different charge selectivity. Large biomolecules, for example, nucleic acid and protein, are precluded from cytoplasmic transfer between cells through gap junction connexin channels.

- Ensures that molecules and current passing through the gap junction do not leak into the intercellular space.

To date, five different functions have been ascribed to gap junction protein:

- Electrical and metabolic coupling between cells

- Electrical and metabolic exchange through hemichannels

- Tumor suppressor genes (Cx43, Cx32 and Cx36)

- Adhesive function independent of conductive gap junction channel (neural migration in neocortex)

- Role of carboxyl-terminal in signaling cytoplasmic pathways (Cx43)

Occurrence and distribution

Gap Junctions have been observed in various animal organs and tissues where cells contact each other. From the 1950s to 1970s they were detected in crayfish nerves,[22] rat pancreas, liver, adrenal cortex, epididymis, duodenum, muscle,[23] Daphnia hepatic caecum,[24] Hydra muscle,[25] monkey retina,[26] rabbit cornea,[27] fish blastoderm,[28] frog embryos,[29] rabbit ovary,[30] re-aggregating cells,[31][32] cockroach hemocyte capsules,[33] rabbit skin,[34] chick embryos,[35] human islet of Langerhans,[36] goldfish and hamster pressure sensing acoustico-vestibular receptors,[37] lamprey and tunicate heart,[38][39] rat seminiferous tubules,[40] myometrium,[41] eye lens[42] and cephalopod digestive epithelium.[43] Since the 1970s gap junctions have continued to be found in nearly all animal cells that touch each other. By the 1990s new technology such as confocal microscopy allowed more rapid survey of large areas of tissue. Since the 1970s even tissues that were traditionally considered to possibly have isolated cells such as bone showed that the cells were still connected with gap junctions, however tenuously.[44] Gap junctions appear to be in all animal organs and tissues and it will be interesting to find exceptions to this other than cells not normally in contact with neighboring cells. Adult skeletal muscle is a possible exception. It may be argued that if present in skeletal muscle, gap junctions might propagate contractions in an arbitrary way among cells making up the muscle. At least in some cases this may not be the case as shown in other muscle types that do have gap junctions.[45] An indication of what results from reduction or absence of gap junctions may be indicated by analysis of cancers[46][47][48] or the aging process.[49]

Functions

Gap junctions may be seen to function at the simplest level as a direct cell to cell pathway for electrical currents, small molecules and ions. The control of this communication allows complex downstream effects on multicellular organisms as described below.

Embryonic, organ and tissue development

In the 1980s, more subtle but no less important roles of gap junction communication have been investigated. It was discovered that gap junction communication could be disrupted by adding anti-connexin antibodies into embryonic cells.[50][51] Embryos with areas of blocked gap junctions failed to develop normally. The mechanism by which antibodies blocked the gap junctions was unclear but systematic studies were undertaken to elucidate the mechanism.[52][53] Refinement of these studies showed that gap junctions appeared to be key to development of cell polarity[54] and the left/right symmetry/asymmetry in animals.[55][56] While signaling that determines the position of body organs appears to rely on gap junctions so does the more fundamental differentiation of cells at later stages of embryonic development.[57][58][59][60][61] Gap junctions were also found to be responsible for the transmission of signals required for drugs to have an effect[62] and conversely some drugs were shown to block gap junction channels.[63]

Gap junctions and the "bystander effect"

Cell death

The "bystander effect" with its connotations of the innocent bystander being killed is also mediated by gap junctions. When cells are compromised due to disease or injury and start to die messages are transmitted to neighboring cells connected to the dying cell by gap junctions. This can cause the otherwise unaffected healthy bystander cells to also die.[64] The bystander effect is, therefore, important to consider in diseased cells, which opened an avenue for more funding and a flourish of research.[65][66][67][68][69][70][71][72][73] Later the bystander effect was also researched with regard to cells damaged by radiation or mechanical injury and therefore wound healing.[74][75][76][77][78] Disease also seems to have an effect on the ability of gap junctions to fulfill their roles in wound healing.[79][80]

Tissue restructuring

While there has been a tendency to focus on the bystander effect in disease due to the possibility of therapeutic avenues there is evidence that there is a more central role in normal development of tissues. Death of some cells and their surrounding matrix may be required for a tissue to reach its final configuration and gap junctions also appear essential to this process.[81][82] There are also more complex studies that try and combine our understanding of the simultaneous roles of gap junctions in both wound healing and tissue development.[83][84] [85]

Areas of electrical coupling

Gap junctions electrically and chemically couple cells throughout the body of most animals. Electrical coupling can be relatively fast acting. Tissues in this section have well known functions observed to be coordinated by gap junctions with inter-cellular signaling happening in time frames of micro-seconds or less.

Heart

Gap junctions are particularly important in cardiac muscle: the signal to contract is passed efficiently through gap junctions, allowing the heart muscle cells to contract in unison. Gap junctions are expressed in virtually all tissues of the body, with the exception of adult fully developed skeletal muscle and mobile cell types such as sperm or erythrocytes. Several human genetic disorders are associated with mutations in gap junction genes. Many of those affect the skin because this tissue is heavily dependent upon gap junction communication for the regulation of differentiation and proliferation. Cardiac gap junctions can pharmacologically be opened with rotigaptide.

Neurons

A gap junction located in neurons is often referred to as an electrical synapse. The electrical synapse was discovered using electrical measurements before the gap junction structure was described. Electrical synapses are present throughout the central nervous system and have been studied specifically in the neocortex, hippocampus, vestibular nucleus, thalamic reticular nucleus, locus coeruleus, inferior olivary nucleus, mesencephalic nucleus of the trigeminal nerve, ventral tegmental area, olfactory bulb, retina and spinal cord of vertebrates.[86]

There has been some observation of weak neuron to glial cell coupling in the locus coeruleus, and in the cerebellum between Purkinje neurons and Bergmann glial cells. It appears that astrocytes are coupled by gap junctions, both to other astrocytes and to oligodendrocytes.[87] Moreover, mutations in the gap junction genes Cx43 and Cx56.6 cause white matter degeneration similar to that observed in Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease and multiple sclerosis.

Connexin proteins expressed in neuronal gap junctions include:

with mRNAs for at least five other connexins (mCx26, mCx30.2, mCx32, mCx43, mCx47) detected but without immunocytochemical evidence for the corresponding protein within ultrastructurally-defined gap junctions. Those mRNAs appear to be down-regulated or destroyed by micro interfering RNAs ( miRNAs ) that are cell-type and cell-lineage specific.

Retina

Neurons within the retina show extensive coupling, both within populations of one cell type, and between different cell types.

Discovery

Naming

Gap junctions were so named because of the "gap" shown to be present at these special junctions between two cells.[88] With the increased resolution of the transmission electron microscope (TEM) gap junction structures were first able to be seen and described in around 1953.

The term "gap junction" appeared to be coined about 16 years later circa 1969.[89][90][91] A similar narrow regular gap was not demonstrated in other intercellular junctions photographed using the TEM at the time.

Form an indicator of function

Well before the demonstration of the "gap" in gap junctions they were seen at the junction of neighboring nerve cells. The close proximity of the neighboring cell membranes at the gap junction lead researchers to speculate that they had a role in intercellular communication, in particular the transmission of electrical signals.[92][93][94] Gap junctions were also proven to be electrically rectifying and referred to as an electrical synapse.[95][96] Later it was found that chemicals could also be transported between cells through gap junctions.[97]

Implicit or explicit in most of the early studies is that the area of the gap junction was different in structure to the surrounding membranes in a way that made it look different. The gap junction had been shown to create a micro-environment between the two cells in the extra-cellular space or "gap". This portion of extra-cellular space was somewhat isolated from the surrounding space and also bridged by what we now call connexon pairs which form even more tightly sealed bridges that cross the gap junction gap between two cells. When viewed in the plane of the membrane by freeze-fracture techniques, higher-resolution distribution of connexons within the gap junction plaque is possible.[98]

Connexin free islands are observed in some junctions. The observation was largely without explanation until vesicles were shown by Peracchia using TEM thin sections to be systematically associated with gap junction plaques.[99] Peracchia's study was probably also the first study to describe paired connexon structures, which he called somewhat simply a "globule". Studies showing vesicles associated with gap junctions and proposing the vesicle contents may move across the junction plaques between two cells were rare, as most studies focused on the connexons rather than vesicles. A later study using a combination of microscopy techniques confirmed the early evidence of a probable function for gap junctions in intercellular vesicle transfer. Areas of vesicle transfer were associated with connexin free islands within gap junction plaques.[100]

Electrical and chemical nerve synapses

Because of the widespread occurrence of gap junctions in cell types other than nerve cells the term gap junction became more generally used than terms such as electrical synapse or nexus. Another dimension in the relationship between nerve cells and gap junctions was revealed by studying chemical synapse formation and gap junction presence. By tracing nerve development in leeches with gap junction expression suppressed it was shown that the bidirectional gap junction (electrical nerve synapse) needs to form between two cells before they can grow to form a unidirectional "chemical nerve synapse".[101] The chemical nerve synapse is the synapse most often truncated to the more ambiguous term "nerve synapse".

Composition

Connexons

The purification[102][103] of the intercellular gap junction plaques enriched in the channel forming protein (connexin) showed a protein forming hexagonal arrays in x-ray diffraction. Now systematic study and identification of the predominant gap junction protein[104] became possible. Refined ultrastructural studies by TEM[105][106] showed protein occurred in a complementary fashion in both cells participating in a gap junction plaque. The gap junction plaque is a relatively large area of membrane observed in TEM thin section and freeze fracture (FF) seen filled with trans-membrane proteins in both tissues and more gently treated gap junction preparations. With the apparent ability for one protein alone to enable intercellular communication seen in gap junctions[107] the term gap junction tended to become synonymous with a group of assembled connexins though this was not shown in vivo. Biochemical analysis of gap junction rich isolates from various tissues demonstrated a family of connexins.[108][109][110]

Ultrastructure and biochemistry of isolated gap junctions already referenced had indicated the connexins preferentially group in gap junction plaques or domains and connexins were the best characterized constituent. It has been noted that the organisation of proteins into arrays with a gap junction plaque may be significant.[29][111] It is likely this early work was already reflecting the presence of more than just connexins in gap junctions. Combining the emerging fields of freeze-fracture to see inside membranes and immunocytochemistry to label cell components (Freeze-fracture replica immunolabelling or FRIL and thin section immunolabelling) showed gap junction plaques in vivo contained the connexin protein.[112][113] Later studies using immunofluorescence microscopy of larger areas of tissue clarified diversity in earlier results. Gap junction plaques were confirmed to have variable composition being home to connexon and non-connexin proteins as well making the modern usage of the terms "gap junction" and "gap junction plaque" non-interchangeable.[114] In other words, the commonly used term "gap junction" always refers to a structure that contains connexins while a gap junction plaque may also contain other structural features that will define it.

The "plaque" or "formation plaque"

Early descriptions of "gap junctions" and "connexons" did not refer to them as such and many other terms were used. It is likely that "synaptic disks"[115] were an accurate reference to gap junction plaques. While the detailed structure and function of the connexon was described in a limited way at the time the gross "disk" structure was relatively large and easily seen by various TEM techniques. Disks allowed researchers using TEM to easily locate the connexons contained within the disk like patches in vivo and in vitro. The disk or "plaque" appeared to have structural properties different from those imparted by the connexons alone.[25] It was thought that if the area of membrane in the plaque transmitted signals the area of membrane would have to be sealed in some way to prevent leakage.[116] Later studies showed gap junction plaques are home to non-connexin proteins making the modern usage of the terms "gap junction" and "gap junction plaque" non-interchangeable as the area of the gap junction plaque may contain proteins other than connexins.[114][117] Just as connexins do not always occupy the entire area of the plaque the other components described in the literature may be only long term or short term residents.[118]

Studies allowing views inside the plane of the membrane of gap junctions during formation indicated that a "formation plaque" formed between two cells prior to the connexins moving in. They were particle free areas when observed by TEM FF indicating very small or no transmembrane proteins were likely present. Little is known about what structures make up the formation plaque or how the formation plaque's structure changes when connexins and other components move in or out. One of the earlier studies of the formation of small gap junctions describes rows of particles and particle free halos.[119] With larger gap junctions they were described as formation plaques with connexins moving into them. The particulate gap junctions were thought to form 4–6 hours after the formation plaques appeared.[120] How the connexins may be transported to the plaques using tubulin is becoming clearer.[54][121]

The formation plaque and non-connexin part of the classical gap junction plaque have been difficult for early researchers to analyse. It appears in TEM FF and thin section to be a lipid membrane domain that can somehow form a comparatively rigid barrier to other lipids and proteins. There has been indirect evidence for certain lipids being preferentially involved with the formation plaque but this cannot be considered definitive.[122][123] It is difficult to envisage breaking up the membrane to analyse membrane plaques without affecting their composition. By study of connexins still in membranes lipids associated with the connexins have been studied.[124] It was found that specific connexins tended to associate preferentially with specific phospholipids. As formation plaques precede connexins these results still give no certainty as to what is unique about the composition of plaques themselves. Other findings show connexins associate with protein scaffolds used in another junction, the zonula occludens ZO1.[125] While this helps us understand how connexins may be moved into a gap junction formation plaque the composition of the plaque itself is still somewhat sketchy. Some headway on the in vivo composition of the gap junction plaque is being made using TEM FRIL.[118][125]

See also

- Gap junction protein

- Electrical synapse

- Connexin

- Connexon

- Ion channel

- Junctional complex

- Intercalated disc

- Cardiac muscle

- Tight junction

- Desmosomes

- Plasmodesma

References

- ↑ White, Thomas W.; Paul, David L. (1999). "Genetic diseases and gene knockouts reveal diverse connexin functions". Annual Review of Physiology. 61 (1): 283–310. PMID 10099690. doi:10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.283.

- ↑ Kelsell, David P.; Dunlop, John; Hodgins, Malcolm B. (2001). "Human diseases: clues to cracking the connexin code?". Trends in Cell Biology. 11 (1): 2–6. PMID 11146276. doi:10.1016/S0962-8924(00)01866-3.

- ↑ Willecke, Klaus; Eiberger, Jürgen; Degen, Joachim; Eckardt, Dominik; Romualdi, Alessandro; Güldenagel, Martin; Deutsch, Urban; Söhl, Goran (2002). "Structural and functional diversity of connexin genes in the mouse and human genome". Biological chemistry. 383 (5): 725–37. PMID 12108537. doi:10.1515/BC.2002.076.

- 1 2 Lampe, Paul D.; Lau, Alan F. (2004). "The effects of connexin phosphorylation on gap junctional communication". The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 36 (7): 1171–86. PMC 2878204

. PMID 15109565. doi:10.1016/S1357-2725(03)00264-4.

. PMID 15109565. doi:10.1016/S1357-2725(03)00264-4. - 1 2 Lampe, Paul D.; Lau, Alan F. (2000). "Regulation of gap junctions by phosphorylation of connexins". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 384 (2): 205–15. PMID 11368307. doi:10.1006/abbi.2000.2131.

- 1 2 Maeda, Shoji; Nakagawa, So; Suga, Michihiro; Yamashita, Eiki; Oshima, Atsunori; Fujiyoshi, Yoshinori; Tsukihara, Tomitake (2009). "Structure of the connexin 26 gap junction channel at 3.5 A resolution". Nature. 458 (7238): 597–602. Bibcode:2009Natur.458..597M. PMID 19340074. doi:10.1038/nature07869.

- 1 2 Alberts, Bruce (2002). Molecular biology of the cell (4th ed.). New York: Garland Science. ISBN 0-8153-3218-1.

- ↑ C. elegans Sequencing, Consortium (Dec 11, 1998). "Genome sequence of the nematode C. elegans: a platform for investigating biology.". Science. 282 (5396): 2012–8. PMID 9851916. doi:10.1126/science.282.5396.2012.

- ↑ Ganfornina, MD; Sánchez, D; Herrera, M; Bastiani, MJ (1999). "Developmental expression and molecular characterization of two gap junction channel proteins expressed during embryogenesis in the grasshopper Schistocerca americana.". Developmental genetics. 24 (1–2): 137–50. PMID 10079517. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1999)24:1/2<137::AID-DVG13>3.0.CO;2-7.

- ↑ Starich, T. A. (1996). "eat-5 and unc-7 represent a multigene family in Caenorhabditis elegans involved in cell-cell coupling". J. Cell Biol. 134 (2): 537–548. PMC 2120886

. PMID 8707836. doi:10.1083/jcb.134.2.537.

. PMID 8707836. doi:10.1083/jcb.134.2.537. - ↑ Simonsen, Karina T.; Moerman, Donald G.; Naus, Christian C. "Gap junctions in C. elegans". Frontiers in Physiology. 5. doi:10.3389/fphys.2014.00040.

- ↑ Barbe, M. T. (1 April 2006). "Cell-Cell Communication Beyond Connexins: The Pannexin Channels". Physiology. 21 (2): 103–114. doi:10.1152/physiol.00048.2005.

- ↑ Panchina, Yuri; Kelmanson, Ilya; Matz, Mikhail; Lukyanov, Konstantin; Usman, Natalia; Lukyanov, Sergey (June 2000). "A ubiquitous family of putative gap junction molecules". Current Biology. 10 (13): R473–R474. PMID 10898987. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00576-5.

- ↑ Lohman, Alexander W.; Isakson, Brant E. "Differentiating connexin hemichannels and pannexin channels in cellular ATP release". FEBS Letters. 588 (8): 1379–1388. PMC 3996918

. PMID 24548565. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2014.02.004.

. PMID 24548565. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2014.02.004. - ↑ Perkins, Guy A.; Goodenough, Daniel A.; Sosinsky, Gina E. (1998). "Formation of the gap junction intercellular channel requires a 30 degree rotation for interdigitating two apposing connexons". Journal of Molecular Biology. 277 (2): 171–7. PMID 9514740. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1997.1580.

- ↑ Hsieh, CL; Kumar, NM; Gilula, NB; Francke, U (Mar 1991). "Distribution of genes for gap junction membrane channel proteins on human and mouse chromosomes.". Somatic cell and molecular genetics. 17 (2): 191–200. PMID 1849321. doi:10.1007/bf01232976.

- ↑ Kumar, NM; Gilula, NB (Feb 1992). "Molecular biology and genetics of gap junction channels.". Seminars in cell biology. 3 (1): 3–16. PMID 1320430. doi:10.1016/s1043-4682(10)80003-0.

- ↑ Kren, BT; Kumar, NM; Wang, SQ; Gilula, NB; Steer, CJ (Nov 1993). "Differential regulation of multiple gap junction transcripts and proteins during rat liver regeneration.". The Journal of Cell Biology. 123 (3): 707–18. PMC 2200133

. PMID 8227133. doi:10.1083/jcb.123.3.707.

. PMID 8227133. doi:10.1083/jcb.123.3.707. - ↑ Chang, Qing; Tang, Wenxue; Ahmad, Shoeb; Zhou, Binfei; Lin, Xi (2008). Schiffmann, Raphael, ed. "Gap junction mediated intercellular metabolite transfer in the cochlea is compromised in connexin30 null mice". PLoS ONE. 3 (12): e4088. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.4088C. PMC 2605248

. PMID 19116647. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004088.

. PMID 19116647. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004088. - ↑ Hu, X; Dahl, G (1999). "Exchange of conductance and gating properties between gap junction hemichannels". FEBS Lett. 451 (2): 113–7. PMID 10371149. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(99)00558-X.

- ↑ Loewenstein WR (July 1966). "Permeability of membrane junctions". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 137 (2): 441–72. Bibcode:1966NYASA.137..441L. PMID 5229810. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1966.tb50175.x.

- ↑ Robertson, JD (February 1953). "Ultrastructure of two invertebrate synapses". Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. 82 (2): 219–23. PMID 13037850. doi:10.3181/00379727-82-20071.

- ↑ Friend DS, Gilula NB (June 1972). "Variations in tight and gap junctions in mammalian tissues". J. Cell Biol. 53 (3): 758–76. PMC 2108762

. PMID 4337577. doi:10.1083/jcb.53.3.758.

. PMID 4337577. doi:10.1083/jcb.53.3.758. - ↑ Hudspeth, AJ; Revel, JP. (Jul 1971). "Coexistence of gap and septate junctions in an invertebrate epithelium". J Cell Biol. 50 (1): 92–101. PMC 2108432

. PMID 5563454. doi:10.1083/jcb.50.1.92.

. PMID 5563454. doi:10.1083/jcb.50.1.92. - 1 2 Hand, AR; Gobel, S (February 1972). "The structural organization of the septate and gap junctions of Hydra". J. Cell Biol. 52 (2): 397–408. PMC 2108629

. PMID 4109925. doi:10.1083/jcb.52.2.397.

. PMID 4109925. doi:10.1083/jcb.52.2.397. - ↑ Raviola, E; Gilula, NB. (Jun 1973). "Gap junctions between photoreceptor cells in the vertebrate retina". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 70 (6): 1677–81. Bibcode:1973PNAS...70.1677R. PMC 433571

. PMID 4198274. doi:10.1073/pnas.70.6.1677.

. PMID 4198274. doi:10.1073/pnas.70.6.1677. - ↑ Kreutziger GO (September 1976). "Lateral membrane morphology and gap junction structure in rabbit corneal endothelium". Exp. Eye Res. 23 (3): 285–93. PMID 976372. doi:10.1016/0014-4835(76)90129-9.

- ↑ Lentz TL, Trinkaus JP (March 1971). "Differentiation of the junctional complex of surface cells in the developing Fundulus blastoderm". J. Cell Biol. 48 (3): 455–72. PMC 2108114

. PMID 5545331. doi:10.1083/jcb.48.3.455.

. PMID 5545331. doi:10.1083/jcb.48.3.455. - 1 2 J Cell Biol. 1974 Jul;62(1) 32-47.Assembly of gap junctions during amphibian neurulation. Decker RS, Friend DS.

- ↑ Albertini, DF; Anderson, E. (Oct 1974). "The appearance and structure of intercellular connections during the ontogeny of the rabbit ovarian follicle with particular reference to gap junctions". J Cell Biol. 63 (1): 234–50. PMC 2109337

. PMID 4417791. doi:10.1083/jcb.63.1.234.

. PMID 4417791. doi:10.1083/jcb.63.1.234. - ↑ Johnson R, Hammer M, Sheridan J, Revel JP; Hammer; Sheridan; Revel (November 1974). "Gap junction formation between reaggregated Novikoff hepatoma cells". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 71 (11): 4536–40. Bibcode:1974PNAS...71.4536J. PMC 433922

. PMID 4373716. doi:10.1073/pnas.71.11.4536.

. PMID 4373716. doi:10.1073/pnas.71.11.4536. - ↑ Knudsen, KA; Horwitz, AF. (1978). "Toward a mechanism of myoblast fusion". Prog Clin Biol Res. 23: 563–8. PMID 96453.

- ↑ Baerwald RJ (1975). "Inverted gap and other cell junctions in cockroach hemocyte capsules: a thin section and freeze-fracture study". Tissue Cell. 7 (3): 575–85. PMID 1179417. doi:10.1016/0040-8166(75)90027-0.

- ↑ Prutkin L (February 1975). "Mucous metaplasia and gap junctions in the vitamin A acid-treated skin tumor, keratoacanthoma". Cancer Res. 35 (2): 364–9. PMID 1109802.

- ↑ Bellairs, R; Breathnach, AS; Gross, M. (Sep 1975). "Freeze-fracture replication of junctional complexes in unincubated and incubated chick embryos". Cell Tissue Res. 162 (2): 235–52. PMID 1237352. doi:10.1007/BF00209209.

- ↑ Orci L, Malaisse-Lagae F, Amherdt M, et al. (November 1975). "Cell contacts in human islets of Langerhans". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 41 (5): 841–4. PMID 1102552. doi:10.1210/jcem-41-5-841.

- ↑ Hama K, Saito K (February 1977). "Gap junctions between the supporting cells in some acoustico-vestibular receptors". J. Neurocytol. 6 (1): 1–12. PMID 839246. doi:10.1007/BF01175410.

- ↑ Shibata, Y; Yamamoto, T (March 1977). "Gap junctions in the cardiac muscle cells of the lamprey". Cell Tissue Res. 178 (4): 477–82. PMID 870202. doi:10.1007/BF00219569.

- ↑ Lorber, V; Rayns, DG (April 1977). "Fine structure of the gap junction in the tunicate heart". Cell Tissue Res. 179 (2): 169–75. PMID 858161. doi:10.1007/BF00219794.

- ↑ McGinley D, Posalaky Z, Provaznik M (October 1977). "Intercellular junctional complexes of the rat seminiferous tubules: a freeze-fracture study". Anat. Rec. 189 (2): 211–31. PMID 911045. doi:10.1002/ar.1091890208.

- ↑ Garfield, RE; Sims, SM; Kannan, MS; Daniel, EE (November 1978). "Possible role of gap junctions in activation of myometrium during parturition". Am. J. Physiol. 235 (5): C168–79. PMID 727239.

- ↑ Goodenough, DA (November 1979). "Lens gap junctions: a structural hypothesis for nonregulated low-resistance intercellular pathways". Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 18 (11): 1104–22. PMID 511455.

- ↑ Boucaud-Camou, Eve (1980). "Junctional structures in digestive epithelia of a cephalopod". Tissue Cell. 12 (2): 395–404. PMID 7414602. doi:10.1016/0040-8166(80)90013-0.

- ↑ Jones SJ, Gray C, Sakamaki H, et al. (April 1993). "The incidence and size of gap junctions between the bone cells in rat calvaria". Anat. Embryol. 187 (4): 343–52. PMID 8390141. doi:10.1007/BF00185892.

- ↑ Sperelakis, Nicholas; Ramasamy, Lakshminarayanan (2005). "Gap-junction channels inhibit transverse propagation in cardiac muscle". Biomed Eng Online. 4 (1): 7. PMC 549032

. PMID 15679888. doi:10.1186/1475-925X-4-7.

. PMID 15679888. doi:10.1186/1475-925X-4-7. - ↑ Larsen WJ, Azarnia R, Loewenstein WR (June 1977). "Intercellular communication and tissue growth: IX. Junctional membrane structure of hybrids between communication-competent and communication-incompetent cells". J. Membr. Biol. 34 (1): 39–54. PMID 561191. doi:10.1007/BF01870292.

- ↑ Corsaro CM, Migeon BR; Migeon (October 1977). "Comparison of contact-mediated communication in normal and transformed human cells in culture". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 74 (10): 4476–80. Bibcode:1977PNAS...74.4476C. PMC 431966

. PMID 270694. doi:10.1073/pnas.74.10.4476.

. PMID 270694. doi:10.1073/pnas.74.10.4476. - ↑ Habermann, H; Chang, WY; Birch, L; Mehta, P; Prins, GS (January 2001). "Developmental exposure to estrogens alters epithelial cell adhesion and gap junction proteins in the adult rat prostate". Endocrinology. 142 (1): 359–69. PMID 11145599. doi:10.1210/en.142.1.359.

- ↑ Kelley, Robert O.; Vogel, Kathryn G.; Crissman, Harry A.; Lujan, Christopher J.; Skipper, Betty E. (March 1979). "Development of the aging cell surface. Reduction of gap junction-mediated metabolic cooperation with progressive subcultivation of human embryo fibroblasts (IMR-90)". Exp. Cell Res. 119 (1): 127–43. PMID 761600. doi:10.1016/0014-4827(79)90342-2.

- ↑ Warner, Anne E.; Guthrie, Sarah C.; Gilula, Norton B. (1984). "Antibodies to gap-junctional protein selectively disrupt junctional communication in the early amphibian embryo". Nature. 311 (5982): 127–31. Bibcode:1984Natur.311..127W. PMID 6088995. doi:10.1038/311127a0.

- ↑ Warner, AE (1987). "The use of antibodies to gap junction protein to explore the role of gap junctional communication during development". Ciba Found. Symp. 125: 154–67. PMID 3030673.

- ↑ Bastide, B; Jarry-Guichard, T; Briand, JP; Délèze, J; Gros, D (April 1996). "Effect of antipeptide antibodies directed against three domains of connexin43 on the gap junctional permeability of cultured heart cells". J. Membr. Biol. 150 (3): 243–53. PMID 8661989. doi:10.1007/s002329900048.

- ↑ Hofer, A; Dermietzel, R (September 1998). "Visualization and functional blocking of gap junction hemichannels (connexons) with antibodies against external loop domains in astrocytes". Glia. 24 (1): 141–54. PMID 9700496. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-1136(199809)24:1<141::AID-GLIA13>3.0.CO;2-R.

- 1 2 3 Francis R, Xu X, Park H; Xu; Park; Wei; Chang; Chatterjee; Lo; et al. (2011). Brandner, Johanna M, ed. "Connexin43 modulates cell polarity and directional cell migration by regulating microtubule dynamics". PLoS ONE. 6 (10): e26379. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...626379F. PMC 3194834

. PMID 22022608. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026379.

. PMID 22022608. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026379. - ↑ Levin, Michael; Mercola, Mark (November 1998). "Gap junctions are involved in the early generation of left-right asymmetry". Dev. Biol. 203 (1): 90–105. PMID 9806775. doi:10.1006/dbio.1998.9024.

- ↑ Levin, M; Mercola, M (November 1999). "Gap junction-mediated transfer of left-right patterning signals in the early chick blastoderm is upstream of Shh asymmetry in the node". Development. 126 (21): 4703–14. PMID 10518488.

- ↑ Bani-Yaghoub, Mahmud; Underhill, T. Michael; Naus, Christian C.G. (1999). "Gap junction blockage interferes with neuronal and astroglial differentiation of mouse P19 embryonal carcinoma cells". Dev. Genet. 24 (1–2): 69–81. PMID 10079512. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1999)24:1/2<69::AID-DVG8>3.0.CO;2-M.

- ↑ Bani-Yaghoub, Mahmud; Bechberger, John F.; Underhill, T.Michael; Naus, Christian C.G. (March 1999). "The effects of gap junction blockage on neuronal differentiation of human NTera2/clone D1 cells". Exp. Neurol. 156 (1): 16–32. PMID 10192774. doi:10.1006/exnr.1998.6950.

- ↑ Donahue, HJ; Li, Z; Zhou, Z; Yellowley, CE (February 2000). "Differentiation of human fetal osteoblastic cells and gap junctional intercellular communication". Am. J. Physiol., Cell Physiol. 278 (2): C315–22. PMID 10666026.

- ↑ Cronier, L.; Frendo, JL; Defamie, N; Pidoux, G; Bertin, G; Guibourdenche, J; Pointis, G; Malassine, A (November 2003). "Requirement of gap junctional intercellular communication for human villous trophoblast differentiation". Biol. Reprod. 69 (5): 1472–80. PMID 12826585. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.103.016360.

- ↑ El-Sabban, M. E.; Sfeir, AJ; Daher, MH; Kalaany, NY; Bassam, RA; Talhouk, RS (September 2003). "ECM-induced gap junctional communication enhances mammary epithelial cell differentiation". J. Cell. Sci. 116 (Pt 17): 3531–41. PMID 12893812. doi:10.1242/jcs.00656.

- ↑ Chaytor, AT; Martin, PE; Evans, WH; Randall, MD; Griffith, TM (October 1999). "The endothelial component of cannabinoid-induced relaxation in rabbit mesenteric artery depends on gap junctional communication". J. Physiol. (Lond.). 520 (2): 539–50. PMC 2269589

. PMID 10523421. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00539.x.

. PMID 10523421. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00539.x. - ↑ Srinivas, M.; Hopperstad, MG; Spray, DC (September 2001). "Quinine blocks specific gap junction channel subtypes". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 (19): 10942–7. Bibcode:2001PNAS...9810942S. PMC 58578

. PMID 11535816. doi:10.1073/pnas.191206198.

. PMID 11535816. doi:10.1073/pnas.191206198. - ↑ Li Bi, Wan; Parysek, Linda M.; Warnick, Ronald; Stambrook, Peter J. (December 1993). "In vitro evidence that metabolic cooperation is responsible for the bystander effect observed with HSV tk retroviral gene therapy". Hum. Gene Ther. 4 (6): 725–31. PMID 8186287. doi:10.1089/hum.1993.4.6-725.

- ↑ Pitts, JD (November 1994). "Cancer gene therapy: a bystander effect using the gap junctional pathway". Mol. Carcinog. 11 (3): 127–30. PMID 7945800. doi:10.1002/mc.2940110302.

- ↑ Colombo, Bruno M.; Benedetti, Sara; Ottolenghi, Sergio; Mora, Marina; Pollo, Bianca; Poli, Giorgio; Finocchiaro, Gaetano (June 1995). "The "bystander effect": association of U-87 cell death with ganciclovir-mediated apoptosis of nearby cells and lack of effect in athymic mice". Hum. Gene Ther. 6 (6): 763–72. PMID 7548276. doi:10.1089/hum.1995.6.6-763.

- ↑ Fick, James; Barker, Fred G.; Dazin, Paul; Westphale, Eileen M.; Beyer, Eric C.; Israel, Mark A. (November 1995). "The extent of heterocellular communication mediated by gap junctions is predictive of bystander tumor cytotoxicity in vitro". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92 (24): 11071–5. Bibcode:1995PNAS...9211071F. PMC 40573

. PMID 7479939. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.24.11071.

. PMID 7479939. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.24.11071. - ↑ Elshami, AA; Saavedra, A; Zhang, H; Kucharczuk, JC; Spray, DC; Fishman, GI; Amin, KM; Kaiser, LR; Albelda, SM (January 1996). "Gap junctions play a role in the 'bystander effect' of the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase/ganciclovir system in vitro". Gene Ther. 3 (1): 85–92. PMID 8929915.

- ↑ Mesnil, Marc; Piccoli, Colette; Tiraby, Gerard; Willecke, Klaus; Yamasaki, Hiroshi (March 1996). "Bystander killing of cancer cells by herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene is mediated by connexins". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 93 (5): 1831–5. Bibcode:1996PNAS...93.1831M. PMC 39867

. PMID 8700844. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.5.1831.

. PMID 8700844. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.5.1831. - ↑ Shinoura, Nobusada; Chen, Lin; Wani, Maqsood A.; Kim, Young Gyu; Larson, Jeffrey J.; Warnick, Ronald E.; Simon, Matthias; Menon, Anil G.; et al. (May 1996). "Protein and messenger RNA expression of connexin43 in astrocytomas: implications in brain tumor gene therapy". J. Neurosurg. 84 (5): 839–45; discussion 846. PMID 8622159. doi:10.3171/jns.1996.84.5.0839.

- ↑ Hamel, W; Magnelli, L; Chiarugi, VP; Israel, MA (June 1996). "Herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase/ganciclovir-mediated apoptotic death of bystander cells". Cancer Res. 56 (12): 2697–702. PMID 8665496.

- ↑ Sacco, MG; Benedetti, S; Duflot-Dancer, A; Mesnil, M; Bagnasco, L; Strina, D; Fasolo, V; Villa, A; et al. (December 1996). "Partial regression, yet incomplete eradication of mammary tumors in transgenic mice by retrovirally mediated HSVtk transfer 'in vivo'". Gene Ther. 3 (12): 1151–6. PMID 8986442.

- ↑ Ripps, Harris (March 2002). "Cell death in retinitis pigmentosa: gap junctions and the 'bystander' effect". Exp. Eye Res. 74 (3): 327–36. PMID 12014914. doi:10.1006/exer.2002.1155.

- ↑ Little, JB; Azzam, EI; De Toledo, SM; Nagasawa, H (2002). "Bystander effects: intercellular transmission of radiation damage signals". Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 99 (1–4): 159–62. PMID 12194273. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.rpd.a006751.

- ↑ Zhou, H; Randers-Pehrson, G; Suzuki, M; Waldren, CA; Hei, TK (2002). "Genotoxic damage in non-irradiated cells: contribution from the bystander effect". Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 99 (1–4): 227–32. PMID 12194291. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.rpd.a006769.

- ↑ Lorimore, SA; Wright, EG (January 2003). "Radiation-induced genomic instability and bystander effects: related inflammatory-type responses to radiation-induced stress and injury? A review". Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 79 (1): 15–25. PMID 12556327. doi:10.1080/0955300021000045664.

- ↑ Ehrlich, HP; Diez, T (2003). "Role for gap junctional intercellular communications in wound repair". Wound Repair Regen. 11 (6): 481–9. PMID 14617290. doi:10.1046/j.1524-475X.2003.11616.x.

- ↑ Coutinho, P.; Qiu, C.; Frank, S.; Wang, C.M.; Brown, T.; Green, C.R.; Becker, D.L. (July 2005). "Limiting burn extension by transient inhibition of Connexin43 expression at the site of injury". Br J Plast Surg. 58 (5): 658–67. PMID 15927148. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2004.12.022.

- ↑ Wang, C. M.; Lincoln, J.; Cook, J. E.; Becker, D. L. (November 2007). "Abnormal connexin expression underlies delayed wound healing in diabetic skin". Diabetes. 56 (11): 2809–17. PMID 17717278. doi:10.2337/db07-0613.

- ↑ Rivera, EM; Vargas, M; Ricks-Williamson, L (1997). "Considerations for the aesthetic restoration of endodontically treated anterior teeth following intracoronal bleaching". Pract Periodontics Aesthet Dent. 9 (1): 117–28. PMID 9550065.

- ↑ Cusato, K; Bosco, A; Rozental, R; Guimarães, CA; Reese, BE; Linden, R; Spray, DC (July 2003). "Gap junctions mediate bystander cell death in developing retina". J. Neurosci. 23 (16): 6413–22. PMID 12878681.

- ↑ Moyer, Kurtis E.; Saggers, Gregory C.; Ehrlich, H. Paul (2004). "Mast cells promote fibroblast populated collagen lattice contraction through gap junction intercellular communication". Wound Repair Regen. 12 (3): 269–75. PMID 15225205. doi:10.1111/j.1067-1927.2004.012310.x.

- ↑ Djalilian, A. R.; McGaughey, D; Patel, S; Seo, EY; Yang, C; Cheng, J; Tomic, M; Sinha, S; et al. (May 2006). "Connexin 26 regulates epidermal barrier and wound remodeling and promotes psoriasiform response". J. Clin. Invest. 116 (5): 1243–53. PMC 1440704

. PMID 16628254. doi:10.1172/JCI27186.

. PMID 16628254. doi:10.1172/JCI27186. - ↑ Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Kovacs, A.; Kanter, E. M.; Yamada, K. A. (February 2010). "Reduced expression of Cx43 attenuates ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction via impaired TGF-beta signaling". Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 298 (2): H477–87. PMC 2822575

. PMID 19966054. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00806.2009.

. PMID 19966054. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00806.2009. - ↑ Ey B, Eyking A, Gerken G, Podolsky DK, Cario E (August 2009). "TLR2 mediates gap junctional intercellular communication through connexin-43 in intestinal epithelial barrier injury". J. Biol. Chem. 284 (33): 22332–43. PMC 2755956

. PMID 19528242. doi:10.1074/jbc.M901619200.

. PMID 19528242. doi:10.1074/jbc.M901619200. - ↑ Connors; Long (2004). "Electrical synapses in the mammalian brain". Annu Rev Neurosci. 27: 393–418. PMID 15217338. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.041002.131128.

- ↑ Orthmann-Murphy, Jennifer L.; Abrams, Charles K.; Scherer, Steven S. (May 2008). "Gap Junctions Couple Astrocytes and Oligodendrocytes". Journal of Molecular Neuroscience. 35 (1): 101–116. PMC 2650399

. PMID 18236012. doi:10.1007/s12031-007-9027-5.

. PMID 18236012. doi:10.1007/s12031-007-9027-5. - ↑ Revel, J. P.; Karnovsky, M. J.; Aitchison, EJ; Smith, EG; Farrell, ID; Gutschik, E (1967). "Hexagonal array of subunits in intercellular junctions of the mouse heart and liver". The Journal of Cell Biology. 33 (3): C7–C12. PMC 2107199

. PMID 6036535. doi:10.1083/jcb.33.3.C7.

. PMID 6036535. doi:10.1083/jcb.33.3.C7. - ↑ Brightman, MW; Reese, TS (March 1969). "Junctions between intimately apposed cell membranes in the vertebrate brain". J. Cell Biol. 40 (3): 648–77. PMC 2107650

. PMID 5765759. doi:10.1083/jcb.40.3.648.

. PMID 5765759. doi:10.1083/jcb.40.3.648. - ↑ Uehara Y, Burnstock G (January 1970). "Demonstration of "gap junctions" between smooth muscle cells". J. Cell Biol. 44 (1): 215–7. PMC 2107775

. PMID 5409458. doi:10.1083/jcb.44.1.215.

. PMID 5409458. doi:10.1083/jcb.44.1.215. - ↑ Goodenough, DA; Revel, JP (May 1970). "A fine structural analysis of intercellular junctions in the mouse liver". J. Cell Biol. 45 (2): 272–90. PMC 2107902

. PMID 4105112. doi:10.1083/jcb.45.2.272.

. PMID 4105112. doi:10.1083/jcb.45.2.272. - ↑ Robertson, J. D. (1953). "Ultrastructure of two invertebrate synapses". Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. 82 (2): 219–23. PMID 13037850. doi:10.3181/00379727-82-20071.

- ↑ Robertson, J. D. (1963). Locke, Michael, ed. Cellular membranes in development. New York: Academic Press. OCLC 261587041.

- ↑ Robertson (1981). "Membrane structure". The Journal of Cell Biology. 91 (3): 189s–204s. JSTOR 1609517. PMC 2112820

. PMID 7033238. doi:10.1083/jcb.91.3.189s.

. PMID 7033238. doi:10.1083/jcb.91.3.189s. - ↑ Furshpan, E. J.; Potter, D. D. (1957). "Mechanism of Nerve-Impulse Transmission at a Crayfish Synapse". Nature. 180 (4581): 342–3. Bibcode:1957Natur.180..342F. PMID 13464833. doi:10.1038/180342a0.

- ↑ Furshpan; Potter, DD (1959). "Transmission at the giant motor synapses of the crayfish" (PDF). The Journal of Physiology. 145 (2): 289–325. PMC 1356828

. PMID 13642302. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1959.sp006143.

. PMID 13642302. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1959.sp006143. - ↑ Payton, B. W.; Bennett, M. V. L.; Pappas, G. D. (December 1969). "Permeability and structure of junctional membranes at an electrotonic synapse". Science. 166 (3913): 1641–3. Bibcode:1969Sci...166.1641P. PMID 5360587. doi:10.1126/science.166.3913.1641.

- ↑ Chalcroft, J. P.; Bullivant, S (October 1970). "An interpretation of liver cell membrane and junction structure based on observation of freeze-fracture replicas of both sides of the fracture". J. Cell Biol. 47 (1): 49–60. PMC 2108397

. PMID 4935338. doi:10.1083/jcb.47.1.49.

. PMID 4935338. doi:10.1083/jcb.47.1.49. - ↑ Peracchia, C (April 1973). "Low resistance junctions in crayfish. II. Structural details and further evidence for intercellular channels by freeze-fracture and negative staining". J. Cell Biol. 57 (1): 54–65. PMC 2108965

. PMID 4120610. doi:10.1083/jcb.57.1.54.

. PMID 4120610. doi:10.1083/jcb.57.1.54. - ↑ Gruijters, W (2003). "Are gap junction membrane plaques implicated in intercellular vesicle transfer?". Cell Biol. Int. 27 (9): 711–7. PMID 12972275. doi:10.1016/S1065-6995(03)00140-9.

- ↑ Todd KL, Kristan WB, French KA (November 2010). "Gap junction expression is required for normal chemical synapse formation". J. Neurosci. 30 (45): 15277–85. PMC 3478946

. PMID 21068332. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2331-10.2010.

. PMID 21068332. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2331-10.2010. - ↑ Goodenough, D. A.; Stoeckenius, W (1972). "The isolation of mouse hepatocyte gap junctions : Preliminary Chemical Characterization and X-Ray Diffraction". The Journal of Cell Biology. 54 (3): 646–56. PMC 2200277

. PMID 4339819. doi:10.1083/jcb.54.3.646.

. PMID 4339819. doi:10.1083/jcb.54.3.646. - ↑ Goodenough, D. A. (1974). "Bulk isolation of mouse hepatocyte gap junctions : Characterization of the Principal Protein, Connexin". The Journal of Cell Biology. 61 (2): 557–63. PMC 2109294

. PMID 4363961. doi:10.1083/jcb.61.2.557.

. PMID 4363961. doi:10.1083/jcb.61.2.557. - ↑ Kumar, N. M.; Gilula, NB (1986). "Cloning and characterization of human and rat liver cDNAs coding for a gap junction protein". The Journal of Cell Biology. 103 (3): 767–76. PMC 2114303

. PMID 2875078. doi:10.1083/jcb.103.3.767.

. PMID 2875078. doi:10.1083/jcb.103.3.767. - ↑ McNutt NS, Weinstein RS (December 1970). "The ultrastructure of the nexus. A correlated thin-section and freeze-cleave study". J. Cell Biol. 47 (3): 666–88. PMC 2108148

. PMID 5531667. doi:10.1083/jcb.47.3.666.

. PMID 5531667. doi:10.1083/jcb.47.3.666. - ↑ Chalcroft, J. P.; Bullivant, S (1970). "An interpretation of liver cell membrane and junction structure based on observation of freeze-fracture replicas of both sides of the fracture". The Journal of Cell Biology. 47 (1): 49–60. PMC 2108397

. PMID 4935338. doi:10.1083/jcb.47.1.49.

. PMID 4935338. doi:10.1083/jcb.47.1.49. - ↑ Young; Cohn, ZA; Gilula, NB (1987). "Functional assembly of gap junction conductance in lipid bilayers: demonstration that the major 27 kd protein forms the junctional channel". Cell. 48 (5): 733–43. PMID 3815522. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(87)90071-7.

- ↑ Nicholson; Gros, DB; Kent, SB; Hood, LE; Revel, JP (1985). "The Mr 28,000 gap junction proteins from rat heart and liver are different but related". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 260 (11): 6514–7. PMID 2987225.

- ↑ Beyer, E. C.; Paul, DL; Goodenough, DA (1987). "Connexin43: a protein from rat heart homologous to a gap junction protein from liver". The Journal of Cell Biology. 105 (6 Pt 1): 2621–9. PMC 2114703

. PMID 2826492. doi:10.1083/jcb.105.6.2621.

. PMID 2826492. doi:10.1083/jcb.105.6.2621. - ↑ Kistler, J; Kirkland, B; Bullivant, S (1985). "Identification of a 70,000-D protein in lens membrane junctional domains". The Journal of Cell Biology. 101 (1): 28–35. PMC 2113615

. PMID 3891760. doi:10.1083/jcb.101.1.28.

. PMID 3891760. doi:10.1083/jcb.101.1.28. - ↑ Staehelin LA (May 1972). "Three types of gap junctions interconnecting intestinal epithelial cells visualized by freeze-etching". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 69 (5): 1318–21. Bibcode:1972PNAS...69.1318S. PMC 426690

. PMID 4504340. doi:10.1073/pnas.69.5.1318.

. PMID 4504340. doi:10.1073/pnas.69.5.1318. - ↑ Gruijters, WTM; Kistler, J; Bullivant, S; Goodenough, DA (1987). "Immunolocalization of MP70 in lens fiber 16-17-nm intercellular junctions". The Journal of Cell Biology. 104 (3): 565–72. PMC 2114558

. PMID 3818793. doi:10.1083/jcb.104.3.565.

. PMID 3818793. doi:10.1083/jcb.104.3.565. - ↑ Gruijters, WTM; Kistler, J; Bullivant, S (1987). "Formation, distribution and dissociation of intercellular junctions in the lens". Journal of Cell Science. 88 (3): 351–9. PMID 3448099.

- 1 2 Gruijters, WTM (1989). "A non-connexon protein (MIP) is involved in eye lens gap-junction formation". Journal of Cell Science. 93 (3): 509–13. PMID 2691517.

- ↑ Robertson, JD (October 1963). "The occurrence of a subunit pattern in the unit membranes of club endings in mauthner cell synapses in goldfish brains". J. Cell Biol. 19 (1): 201–21. PMC 2106854

. PMID 14069795. doi:10.1083/jcb.19.1.201.

. PMID 14069795. doi:10.1083/jcb.19.1.201. - ↑ Loewenstein WR, Kanno Y (September 1964). "Studies on an epithelial (gland) cell junction. I. Modifications of surface membrane permeability". J. Cell Biol. 22 (3): 565–86. PMC 2106478

. PMID 14206423. doi:10.1083/jcb.22.3.565.

. PMID 14206423. doi:10.1083/jcb.22.3.565. - ↑ Gruijters, WTM (2003). "Are gap junction membrane plaques implicated in intercellular vesicle transfer?". Cell Biology International. 27 (9): 711–7. PMID 12972275. doi:10.1016/S1065-6995(03)00140-9.

- 1 2 Ozato-Sakurai N, Fujita A, Fujimoto T (2011). Wong, Nai Sum, ed. "The distribution of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate in acinar cells of rat pancreas revealed with the freeze-fracture replica labeling method". PLoS ONE. 6 (8): e23567. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...623567O. PMC 3156236

. PMID 21858170. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023567.

. PMID 21858170. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023567. - ↑ Decker, RS; Friend, DS (July 1974). "Assembly of gap junctions during amphibian neurulation". J. Cell Biol. 62 (1): 32–47. PMC 2109180

. PMID 4135001. doi:10.1083/jcb.62.1.32.

. PMID 4135001. doi:10.1083/jcb.62.1.32. - ↑ Decker, RS (June 1976). "Hormonal regulation of gap junction differentiation". J. Cell Biol. 69 (3): 669–85. PMC 2109697

. PMID 1083855. doi:10.1083/jcb.69.3.669.

. PMID 1083855. doi:10.1083/jcb.69.3.669. - ↑ Lauf U, Giepmans BN, Lopez P, Braconnot S, Chen SC, Falk MM; Giepmans; Lopez; Braconnot; Chen; Falk (August 2002). "Dynamic trafficking and delivery of connexons to the plasma membrane and accretion to gap junctions in living cells". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 (16): 10446–51. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9910446L. PMC 124935

. PMID 12149451. doi:10.1073/pnas.162055899.

. PMID 12149451. doi:10.1073/pnas.162055899. - ↑ Meyer, R; Malewicz, B; Baumann, WJ; Johnson, RG (June 1990). "Increased gap junction assembly between cultured cells upon cholesterol supplementation". J. Cell. Sci. 96 (2): 231–8. PMID 1698798.

- ↑ Johnson, R. G.; Reynhout, J. K.; Tenbroek, E. M.; Quade, B. J.; Yasumura, T.; Davidson, K. G. V.; Sheridan, J. D.; Rash, J. E. (January 2012). "Gap junction assembly: roles for the formation plaque and regulation by the C-terminus of connexin43". Mol. Biol. Cell. 23 (1): 71–86. PMC 3248906

. PMID 22049024. doi:10.1091/mbc.E11-02-0141.

. PMID 22049024. doi:10.1091/mbc.E11-02-0141. - ↑ Locke, Darren; Harris, Andrew L (2009). "Connexin channels and phospholipids: association and modulation". BMC Biol. 7 (1): 52. PMC 2733891

. PMID 19686581. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-7-52.

. PMID 19686581. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-7-52. - 1 2 Li X, Kamasawa N, Ciolofan C, et al. (September 2008). "Connexin45-containing neuronal gap junctions in rodent retina also contain connexin36 in both apposing hemiplaques, forming bihomotypic gap junctions, with scaffolding contributed by zonula occludens-1". J. Neurosci. 28 (39): 9769–89. PMC 2638127

. PMID 18815262. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2137-08.2008.

. PMID 18815262. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2137-08.2008.

Further reading

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gap junctions. |

- Gap Junctions at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)