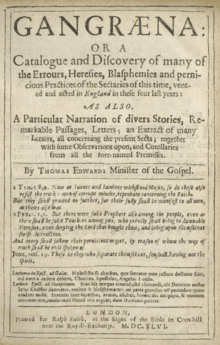

Gangraena

Gangraena is a book by English puritan clergyman Thomas Edwards, published in 1646. A notorious work of "heresiography", i.e. the description in detail of heresy, it appeared the year after Ephraim Pagitt's Heresiography. These two books attempted to catalogue the fissiparous Protestant congregations of the time, in England particularly, into recognised sects or beliefs. Pagitt worked with 40 to 50 categories, Edwards went further with around three times as many, compiling a list of the practices of the Independents and more extreme radicals:

| “ | Thomas Edwards, in his Gangraena (1645), enumerated, with uncritical exaggeration, no less than sixteen sects and one hundred and seventy-six miscellaneous "errors, heresies and blasphemies," exclusive of popery and deism.[1] | ” |

Nature of Gangraena

Gangraena is generally described as an alarmist work, deducing a collapse of national polity from the ramification of different religious creeds. Typically, the Baptist Hanserd Knollys was accused of being an Anabaptist.[2] Heresy is foregrounded, and the analogy suggested that heresy is to the soul as witchcraft to the body.[3] Edwards was an unsparing writer and Gangraena is described as "monumentally vituperative".[4] The title itself refers to 2 Timothy 2:17, and "canker" in the King James translation.

It is not really a unified work, called a "complex, ramshackle text" by Nicholas Tyacke.[5] It appeared in three volumes, with information added from correspondents, and Richard Baxter in particular was also a contributor.[6] Scholarly opinions on it are now mixed, having in the past been somewhat dismissive of the work as paranoid and probably counter-productive in the way of providing and circulating a menu of "heretical" options. Some scholars now see it as made more coherent by its inferences from and to the diabolical element, and more readable casually for the audience of the times, than it has in the past been allowed credit.[7]

Reception

It provoked over 30 pamphlet responses in the period 1646-7, mostly hostile.[8] Among them were works by Jeremiah Burroughes,[9] John Goodwin,[10] John Lilburne, John Saltmarsh and William Walwyn.

Notes

- ↑ http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/hcc7.ii.i.xii.html

- ↑ Barry H. Howson, Erroneous and Schismatical Opinions: The Questions of Orthodoxy Regarding the Theology of Hanserd Knollys (c. 1599-1691) (2001), p. 1.

- ↑ John Marshall, John Locke, Toleration and Early Enlightenment Culture: Religious Intolerance and Arguments for Religious Toleration in Early Modern and 'early Enlightenment' Europe (2006), p. 287.

- ↑ Thomas N. Corns, A Companion to Milton (2003), p. 142.

- ↑ Nicholas Tyacke, England's Long Reformation 1500-1800 (1998), p. 241.

- ↑ William Lamont (1979), Richard Baxter and the Millennium p. 252.

- ↑ Nathan Johnstone, The Devil and Demonism in Early Modern England (2006), p. 258.

- ↑ Ann Hughes, "Popular" Presbyterianism in the 1640s and 1650s: the cases of Thomas Edwards and Thomas Hall, p. 248 in Nicholas Tyacke (editor), England's Long Reformation, 1500-1800 (1998).

- ↑ A Vindication of Mr Burroughes, against Mr Edwards his foule aspersions in his spreading Gangraena, and his angry Antiapologia (1646).

- ↑ Cretensis, or, A briefe answer to an ulcerous treatise lately published by Mr. Thomas Edwards, intituled Gangraena; calculated for the meridian of such passages in the said treatise which relate to Mr. John Goodwin, but may without any sensible error indifferently serve for the whole tract etc. (1646), anonymous.

Further reading

- Ann Hughes, Gangraena and the Struggle for the English Revolution, New York: Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 0-19-925192-4